![]()

1

The Idea of the City of Refuge

And among the cities which ye shall give unto the Levites there shall be six cities for refuge.

(NUMBERS 35:6, KJV)

Almost every society has an image of a perfect world, however vague its outlines and imprecise its coordinates. It can loom dimly in the past as a remote golden age—a lost Arcadia—or as a prophecy of things to come, in this world or the next. It can be a purely philosophical exercise like Plato’s Republic, or a political promise, the alluring dream of a socialist workers’ paradise. It scarcely matters that this perfect world is unattainable. The more distant and remote the vision, the better to cudgel the present and to expose its faults and failings.

Five hundred years ago, Thomas More published a book that made it possible for the first time to speak collectively of all these notions of perfection, whether mythical, philosophical, theological, or merely administrative. His title coined that brilliant new word, the sonorous and immensely suggestive Utopia, which subsumed all these different conceptions of human perfection—Greek and Roman, Jewish and Christian—into a single irresistible vision. This vision has become a potent force in Western culture, where radical campaigns for social reform soon came to arouse the kind of rapturous millennial hopes once restricted to heavenly paradise. A good portion of the history of the past five centuries is the story of utopian revolutions and their consequences.1

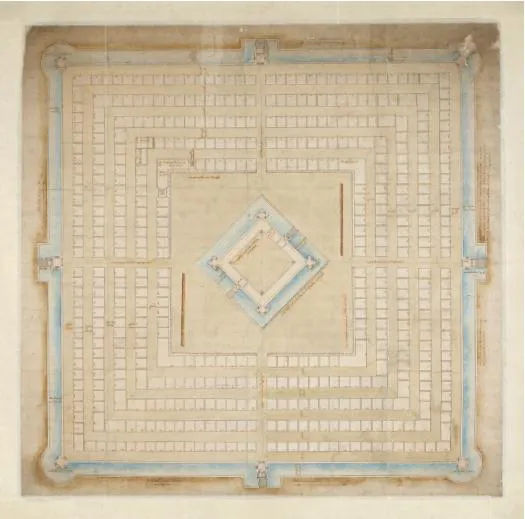

FIG. 1 The city of refuge is the dissenters’ Utopia, a foursquare sanctuary for the refugees displaced by the religious wars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Freudenstadt in Swabia was designed by Heinrich Schickhardt in 1599, for whom rectilinear order was so important that he bent the church on the main square rather than violate his regular plan.

This is the main utopian tradition, which aspires to perfect the world and liberate it from strife, want, and woe. But alongside it runs a second strand of thought that recognizes that the corrupt world, however much we tamper and tinker, cannot be made perfect, and that squalor and discord are the natural state of baffled human existence. This alternative tradition was carried forward by sects that had received their fill of official harassment and unofficial violence, including German Rappites, French Huguenots, and American Shakers. Seeing no hope for reforming a wicked world, they chose instead to withdraw from it. They made their way to distant sanctuaries, where they withdrew from society to establish detached and independent communities in isolation, rarely numbering more than one or two thousand inhabitants. Although they varied in their beliefs and nationality, they were keenly interested in one another. Visual motifs and forms passed from one to another like a baton in a relay race, remaining intact but taking on new symbolic meaning with each transfer. All were drawn by a single tantalizing image, that of a “city of refuge.” In character it was orderly, with repeated house types and a regular street plan; in shape it was usually a square (fig. 1). These separatist enclaves, dissimilar in theology but similar in their urban practice, form a distinct and unbroken intellectual tradition, one that runs parallel to the main channel of utopian thought. It is the living continuity of that tradition that is the theme of this book.

The phrase “city of refuge” derives from the Bible, for it was only logical that Christian societies suffering persecution and seeking sanctuary look there to find solace and guidance. It was natural that they should identify themselves with the ancient Israelites on their exodus through the wilderness, and even that their towns should imitate the layout of the Israelite encampments during those wanderings. But the Bible offers another image for persecuted refugees, a strangely hopeful one, and that is the city of refuge described in the book of Numbers. There we read how Moses, following God’s instructions, allocated the Promised Land among the twelve tribes of Israel. Forty-eight cities were to be given to the Levite tribe; of these six were awarded the special designation of “cities of refuge” (טלקמ ריע in Hebrew, Orei Miklat). Someone guilty of manslaughter could flee to one of these cities without fear of being avenged by the victim’s family:

And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, Speak to the people of Israel and say to them, When you cross the Jordan into the land of Canaan, then you shall select cities to be cities of refuge for you, that the manslayer who kills any person without intent may flee there. The cities shall be for you a refuge from the avenger, that the manslayer may not die until he stands before the congregation for judgment. And the cities that you give shall be your six cities of refuge. You shall give three cities beyond the Jordan, and three cities in the land of Canaan, to be cities of refuge. These six cities shall be for refuge for the people of Israel, and for the stranger and for the sojourner among them, that anyone who kills any person without intent may flee there.

(NUM. 35:9 15)

Only much later in the Bible (Josh. 20:7–8) are the names of those six cities revealed: Kadesh, Shechem, and Hebron on the east side of the Jordan, and Bezer, Ramoth, and Golan on the west.2 A glance at a map shows that they are spaced across ancient Israel with remarkable evenness, according not to population but geography, thereby reducing as much as possible the longest potential flight of a fugitive. A refuge needs to be close at hand.

The ancient Israelites hardly invented the idea of a sacred refuge, which is found everywhere in the ancient world. We do not know its historical origin, only that it is very old. It is older than the ancient Greeks, who knew it from the Iliad and who already had a well-established practice of designating certain temples or altars as places where a fugitive might claim asylum. This was done not for the sake of the fugitive but for that of the temple, which any act of violence would defile.3 The Greeks refused to drag fugitives out forcibly from their temples (although, as the Spartan general Pausanias found, they were quite willing to starve them out). Christianity continued this ancient practice, which was formalized in 511 at the First Council of Orléans, which granted the right of asylum to anyone who could make his way to a church or the house of a bishop. Hence, the English word sanctuary signifies both a place of refuge and the holiest part of a church building.

But the Jewish tradition was unusual in declaring not merely a temple or altar but an entire city as a sanctuary.4 This is an enormously arresting idea, yet the Christian Middle Ages had no great interest in its Jewish roots. If medieval theologians contemplated the city of refuge, it was only because it prefigured the coming of Christ.5 And so the idea slumbered through the centuries, right until the dawning of the Protestant Reformation.

The savage campaign to extirpate the Hussites (1420–37), the followers of Jan Hus, brought to Europe the age of religious wars. For the next two centuries, the roads of Europe would be crammed with refugees, whole populations drawing carts or lugging packs, all in search of asylum. And the peace that eventually settled over Europe did little to stem the stream of refugees. The stern doctrine of Cuius regio, eius religio (Whose realm, his religion) imposed the faith of the prince or duke on his people, which gave the dissenter but two choices: to conform or to flee. Under these new circumstances, it was possible to look with new eyes at the ancient doctrine of the city of refuge—a holy sanctuary not for the solitary refugee but for an entire population. And so the city of refuge was revived and transformed, in the process becoming something that the ancient Israelites could not have recognized.

+ + + +

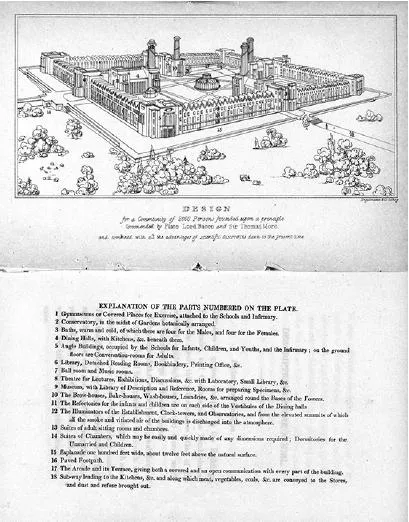

Something odd happened to those separatist societies who came to build their own cities of refuge. The further they retreated into the wilderness, the more they were noticed and scrutinized. The less they cared about the world, the more the world cared about them. Their religious enclaves were avidly studied by reformers whose motives were not in the slightest religious, and who regarded these self-contained societies as experimental laboratories in which new systems of economy, administration, and family structure could be tested and evaluated. When they came to envision their own ideal societies, they naturally drew on the example of their religious counterparts. Brook Farm, the communal society established by Boston Transcendentalists in 1841, was inspired by the settlements of Shakers, Harmonists, and Moravians, as their earliest printed prospectuses make clear.6 Robert Owen imitated the economic structure of the Rappites, with their sophisticated agriculture and industry, and economic self-sufficiency (fig. 2). Charles Fourier learned from the vast communal buildings of the Shakers that functioned as dormitories, dining halls, and meetinghouses. James Silk Buckingham embraced the most durable and widespread feature of these religious sanctuaries—the belief that the right angle and the square are the most divine of all geometric forms.

FIG. 2 When Marx and Engels spoke of “socialist Utopias,” they meant projects like Robert Owen’s New Harmony, Indiana, shown here in an imaginary view of 1825. Owen expressed his radically new socioeconomic order in terms of visionary architecture, most spectacularly in the four ventilation towers that he called “illuminators,” which were to be outfitted with gas-burners that would light up the town by night.

It is startling that these social reformers should look so closely at these religious enclaves, given the wide divergence in their beliefs, as wide as the gap between the free love libertinism of Owen and the stony chastity of the Shakers. Yet similar circumstances prompt similar solutions. Each sought to create overnight an entirely new social order—entirely self-contained and self-sufficient, and remote enough from the world so that the social experiment would not be contaminated—and it was only natural that the secular reformers should borrow from the experiments of their religious predecessors, and modify them. The same model dormitory built to enforce celibacy on the eve of the Millennium could also serve to pry children away from the corrupting influence of their parents. The same grid that represents the “city that lies foursquare” in the book of Revelation could also express utilitarian rationality. Even the all-controlling codes of behavior, the meddling moralism that Fourier and others practiced, were inspired by the way that religious leaders could direct the private lives of their adherents.

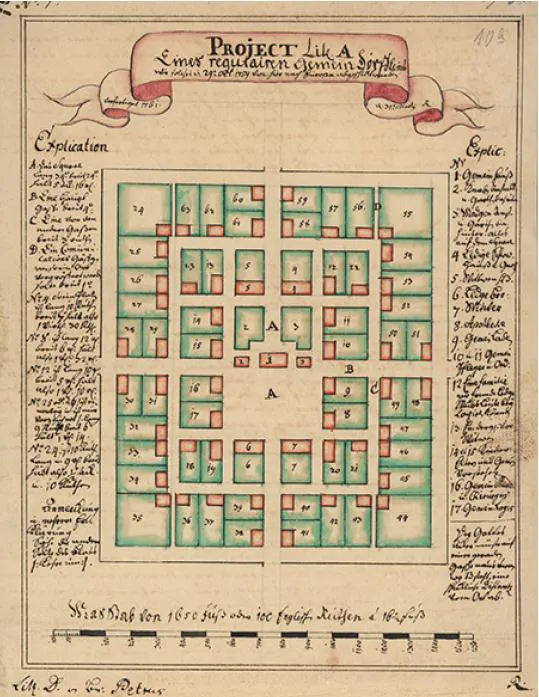

Yet despite this productive cross-fertilization, religious and secular communal societies have generally been treated by scholars as separate and distinct entities; their underlying and essential continuity has been overlooked. Where they have not been studied in isolation, they have been flung together under the general rubric of communal Utopias. Or ignored completely: Lewis Mumford’s The Story of Utopias confidently identified a “gap in the Utopian tradition from seventeenth century to the nineteenth.”7 And yet in precisely this gap came the great flowering of Pietist utopianism (fig. 3). More recently, Robert P. Sutton’s otherwise splendid Communal Utopias and the American Experience segregates religious and secular communities into separate volumes; the result is to cut the extraordinary story of New Harmony, Indiana, into two halves, when its most fascinating aspect falls into the space between them, the lively exchange between the religious leader and the secular reformer. This segregation of religious from secular Utopians, usually at the expense of the former, dates back to at least 1880, when Friedrich Engels omitted all mention of religious reformers in his Socialism: Utopian and Scientific in 1880. And yet the same Engels, as we shall see, dealt at great length with them in his earlier writings, even analyzing the plight of factory workers in Europe by comparing them to their counterparts in George Rapp’s Harmony Society. This book is meant to serve as a corrective to this inherited Marxist viewpoint, which continues to shape our thinking and obscures the fundamental relationship between these two utopian currents, which played a consequential part in making the world in which we live.

+ + + +

Because the city of refuge is a living tradition and not the exclusive property of any denomination, its boundaries are somewhat elastic. This book will look at sanctuaries built to house religious refugees (such as Freudenstadt and the settlements of the Moravians), those built by charismatic communal leaders (the three towns created by George Rapp), and even some that were purely imaginary (those planned by Albrecht Dürer and Johann Valentin Andreae). The socialist Utopias of the early nineteenth century stand at the culmination of this tradition, refuges not from religious persecution but—as they might put it—industrial capitalism. Readers might be surprised to find New Haven and Philadelphia included here, but their founders were linked to the tight circle of thinkers who kept the idea of the city of refuge alive. At the same time, not all communal separatists built such towns. The millenarian settlement that Conrad Beissel founded in Ephrata, Pennsylvania, in 1735 was quite sophisticated—with a refined musical culture, weaving and pottery factories, and a prolific printing press—but it had no urban form (fig. 4).8 Nor did the settlements of the Shakers, who will not be treated comprehensively here. Although they are central to the story of communal utopianism and would produce the most sophisticated of all communal building types, they stood outside the German intellectual-theological tradition that is the subject here. Like the Ephrata Cloisterites, they did not give their settlements the formal geometric unity that is the hallmark of the city of refuge.9

FIG. 3 The Moravian Church, revived under Count Nicholas Zinzendorf in 1727, translated the beliefs of German Pietism in...