![]()

PART 1

THE APPEAL OF PHYSIOGNOMY

![]()

1

THE PHYSIOGNOMISTS’ PROMISE

Agnieszka Holland’s movie Europa Europa is based on the autobiography of Solomon Perel. As a German Jewish boy, Perel is forced to escape Nazi Germany. After a chain of events that includes stints in Poland and Russia, he is captured by German soldiers. To save his life, he pretends to be Josef Peters, a German from Baltic Germany. Eventually he wins the admiration of the soldiers and their commanding officer and is sent to a prestigious Hitler Youth School in Berlin. One of his scariest moments at the school occurs during a science lesson on racial purity. Next to the giant swastika flag hang three large posters showing faces overlaid with measurements. The teacher walks in and asks, “how do you recognize a Jew?” and then continues, “that’s quite simple. The composition of Jewish blood is totally different from ours. The Jew has a high forehead, a hooked nose, a flat back of the head, ears that stick out and he has an ape-like walk. His eyes are shifty and cunning.” In contrast to the Jewish man, “the Nordic man is the gem of this earth. He’s the most glowing example of the joy of creation. He is not only the most talented but the most beautiful. His hair is as light as ripened wheat. His eyes are blue like the summer sky. His movements are harmonious. His body is perfect.” The teacher continues, “science is objective. Science is incorruptible. As I have already told you, if you thoroughly understand racial differences, no Jew will ever be able to deceive you.” This is where the frightening moment for Perel/Peters really begins. The teacher turns toward Peters and asks him to come forward. Horrified, Peters reluctantly goes to the front of the room. The teacher pulls out a measuring tape and starts measuring his head—first from the chin to the top of the head, then from the nose to the top of the head, and then from the chin to the nose. While the measurement continues, there is a close up on Peters’s face as he anxiously tracks the actions of the teacher. The teacher continues with his measurement. He measures the width of Peters’s head and then compares his eyes with different eye colors from a table. “The eyes. Look at his skull. His forehead. His profile [turning Peters’s head, who is visibly blushing]. Although his ancestors’ blood, over many generations mingled with that of other races, one still recognizes his distinct Aryan traits.” On hearing this, Peters almost jerks his head toward the teacher’s face. “It’s from this mixture that the East-Baltic race evolved. Unfortunately, you’re not part of our most noble race, but you are an authentic Aryan.”

The “objective science” of physiognomy was not invented by Nazi scientists. It has a long history originating in ancient cultures. The physiognomists’ claims reached scientific credibility in the nineteenth century, although this credibility came under attack by the new science of psychology in the early twentieth century. Their claims were wrong, but the physiognomists were right about a few things: we immediately form impressions from appearance, we agree on these impressions, and we act on them. These psychological facts make the physiognomists’ claims believable, and the claims have not disappeared. A surge of recent scientific studies test hypotheses that the physiognomists would have approved of. An Israeli technology start-up is offering its services in facial profiling to private businesses and governments. Rather than using a tape to measure faces, they use modern computer science methods. Their promise is the old physiognomists’ promise: “profiling people and revealing their personality based only on their facial image.” We are tempted by the physiognomists’ promise, because it is easy to confuse our immediate impressions from the face with seeing the character of the face owner. Grasping the appeal of this promise and the significance of first impressions in everyday life begins with the history of physiognomy and its inherent connections to “scientific” racism.

The first preserved document dedicated to physiognomy is Physiognomica, a treatise attributed to Aristotle. The major premises of the treatise are that the character of animals is revealed in their form and that humans resembling certain animals possess the character of these animals. Here is one of many examples of applying this logic: “soft hair indicates cowardice, and coarse hair courage. This inference is based on observation of the whole animal kingdom. The most timid of animals are deer, hares, and sheep, and they have the softest coats; whilst the lion and wild-boar are bravest and have the coarsest coats.” The logic is also extended to races: “and again, among the different races of mankind the same combination of qualities may be observed, the inhabitants of the north being brave and coarse-haired, whilst southern peoples are cowardly and have soft hair.”

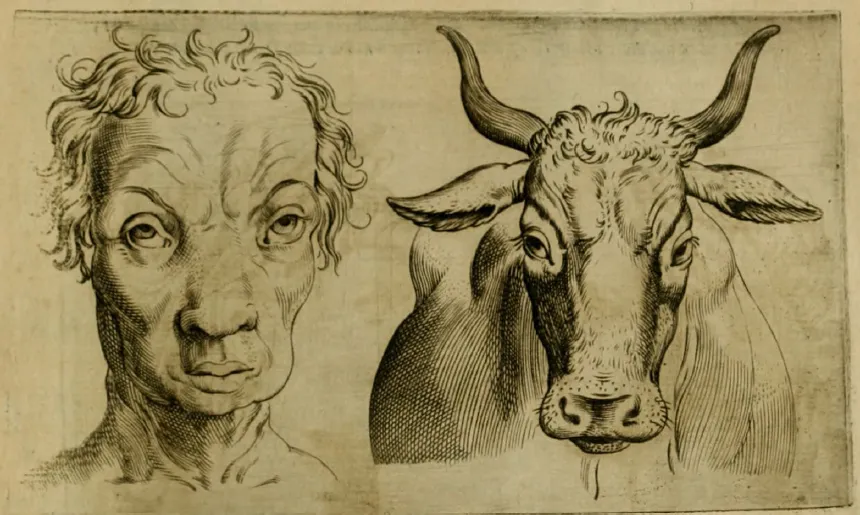

In the sixteenth century, Giovanni Battista della Porta, an Italian scholar and playwright, greatly expanded on these ideas. Humans whose faces (and various body parts) “resembled” a particular animal were endowed with the presumed qualities of the animal. His book is filled with illustrations like the one in Figure 1.1.

FIGURE 1.1. An illustration from Giovanni Battista della Porta’s De Humana Physiognomia. Della Porta’s book, in which he inferred the character of people from their supposed resemblance to animals, was extremely popular and influenced generations of physiognomists.

This particular illustration appears four times in the book in analyses of different facial parts, yet the message is consistent. People who look like cows—whether because of their big foreheads or wide noses—are stupid, lazy, and cowardly. There is one positive characteristic: the hollow eyes indicate pleasantness. As you can imagine, those who “look like” lions come off much better.

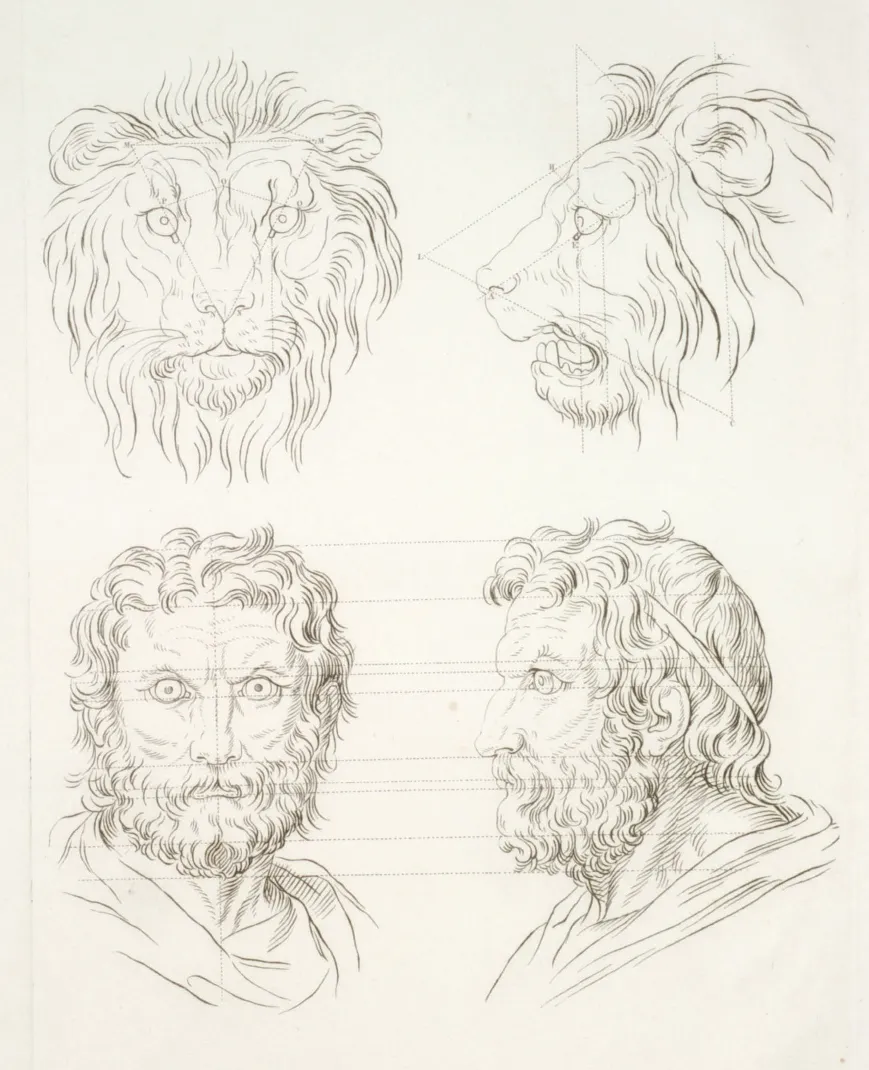

Della Porta’s book was very popular in Europe and enjoyed multiple translations from Latin into Italian, German, French, and Spanish, resulting in twenty editions. The book influenced Charles Le Brun, one of the dominant figures in seventeenth-century French art. Le Brun, appointed by Louis XIV as the first Painter of the King, was also the Director of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture. In 1688, Le Brun delivered a lecture on the facial expressions of emotions: the first attempt in human history to systematically explore and depict such expressions. After Le Brun’s death, the lecture—discussed, admired, and hated by artists—was published in more than sixty editions. Le Brun also delivered a second lecture on physiognomy. Unfortunately, this lecture was not preserved, but some of the illustrations survived. Compare della Porta’s Lion-Man in Figure 1.2 with Le Brun’s Lion-Man in Figure 1.3.

FIGURE 1.2. Another illustration from Giovanni Battista della Porta’s De Humana Physiognomia. Compare this illustration with Figure 1.3.

Le Brun’s drawings are more beautiful and true to life, and it is apparent that he was trying to develop a much more sophisticated system of comparisons between animal and human heads. Le Brun experimented with the angles of the eyes to achieve different perceptual effects. He noted that the eyes of human faces are on a horizontal line and that sloping them downward makes the faces look more bestial. This is illustrated in his drawing of the Roman emperor, Antoninus Pius, in Figure 1.4.

FIGURE 1.3. After Charles Le Brun, lion and lion-man. Le Brun was developing a system for comparing animal and human faces.

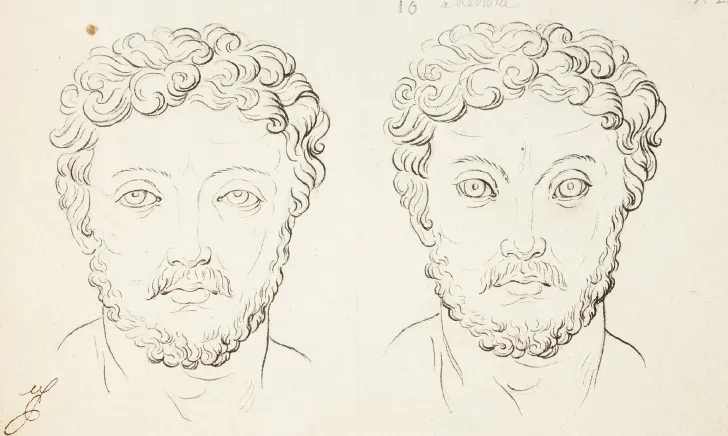

FIGURE 1.4. Charles Le Brun, Antoninus Pius with sloping eyes. Le Brun experimented with the angle of the eyes to make humans look more like animals.

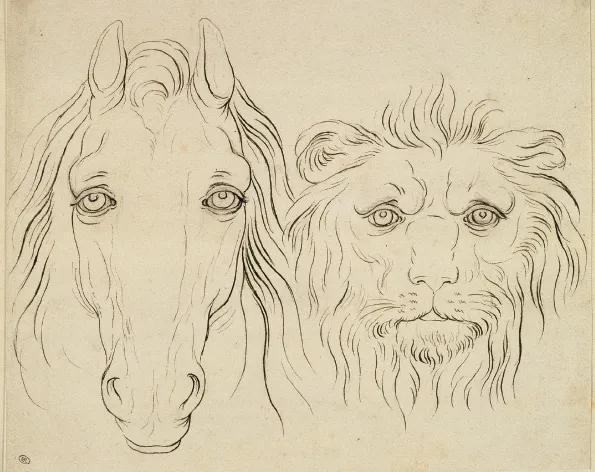

Alternatively, making the eyes of animals horizontal makes them look more human, as in Figure 1.5. These kinds of experiments are not that different from modern psychology experiments testing how changes in facial features influence our impressions.

FIGURE 1.5. Charles Le Brun, horse and lion with horizontal eyes. Le Brun experimented with the angle of the eyes to make animals look more like humans.

The theme of comparative physiognomy would continue to run through physiognomists’ writings and appear in the work of many caricaturists throughout Europe and America for the next 300 years. Some of the most talented caricaturists, like Thomas Rowlandson in England and Honoré Daumier and J. J. Grandville in France, would exploit this theme to achieve humorous effects. But other authors took the theme seriously. Many national stereotypes and prejudices of the day find their expression in a book titled Comparative Physiognomy or Resemblances between Men and Animals, published in the United States in 1852: Germans are like lions, Irish are like dogs, Turks are like turkeys, and the list goes on.

Johann Kaspar Lavater, the real superstar of physiognomy, highly recommended della Porta’s book, although he was critical: “the fanciful Porta appears to me to have been often misled, and to have found resemblances [between men and beasts] which the eye of truth never could discover.” Prior to Lavater, physiognomy was closely associated with suspect practices like chiromancy (palm reading), metoposcopy (reading the lines of the forehead), and astrology. There were even laws in Britain stating that those “pretending to have skill in physiognomy” were “rogues and vagabonds,” “liable to be publicly whipped.” Lavater engaged in debates with some of the greatest minds of the eighteenth century and legitimized physiognomy. Reviewing the history of physiognomy at the end of the nineteenth century, Paolo Mantegazza, an Italian neurologist and anthropologist, summarized it this way: “plenty of authors, plenty of volumes, but little originality, and plenty of plagiarism! Who knows how often we might have been dragged through the same ruts if towards the middle of the last century Lavater had not appeared to inaugurate a new era for this order of studies.” For Mantegazza, Lavater was “the apostle of scientific physiognomy.”

Born and raised in Zurich, Switzerland, Lavater showed early inclinations toward religion. After receiving a theological education, he rose through the ranks of the Zurich Reformed Church to become the pastor of the Saint Peter’s church. By many accounts of the day, he was extremely charming. His sermons were popular, and he entertained hundreds of visitors. Lavater was also a prolific author. He managed to write more than 100 books and maintain an extremely large correspondence. Ironically, he was reluctant to write about physiognomy, although he was continually urged to do so by Johann Georg Ritter von Zimmermann, another Swiss who was the personal physician of the King of England and a European celebrity. Zimmermann would remain Lavater’s greatest promoter and supporter.

Lavater’s first publication on physiognomy was unintentional. As a member of the Society for Natural Sciences in Zurich, Lavater was asked to deliver a lecture of his own choosing. He gave a lecture on physiognomy, which ended up being published by Zimmermann, who “had it printed wholly without my knowledge. And thus I suddenly saw myself thrust into public as a defender of physiognomics.” Being thrust into this role and aware of the strong feelings that physiognomy provoked, Lavater approached many celebrities of the day to help him with the writing of his Essays on Physiognomy. By then, he was a famous theologian, and support was coming from all directions—from encouragement to requests for portraits to be analyzed. None other than Goethe helped Lavater edit the first volume, and some of the best illustrators worked on the books. The four-volume work was published between 1775 and 1778, and the result was “a typographical splendor with which no German book had ever before been printed.” And in fact, the large format, richly illustrated books are beautiful even by today’s standards.

The success of the books was phenomenal despite the exorbitant price. It helped that the books were distributed by subscription to many aristocrats and leading intellectuals, some of whom were lured by Lavater’s promise to analyze their profiles. More importantly, societies formed to buy and discuss the books. Within a few decades, there were twenty English, sixteen German, fifteen French, two American, one Russian, one Dutch, and one Italian editions. As the author of the Lavater obituary in The Gentleman’s Magazine in 1801 put it, “in Switzerland, in Germany, in France, even in Great Britain, all the world became passionate admirers of the Physiognomical Science of Lavater. His books, published in the German language, were multiplied by many editions. In the enthusiasm with which they were studied and admired, they were thought as necessary in every family as even the Bible itself. A servant would, at one time, scarcely be hired but the description and engravings of Lavater had been consulted in careful comparisons with the lines and features of the young man’s or woman’s countenance.”

Lavater defined physiognomy as “the talent of discovering, the interior man by the exterior appearance.” Although his ambition was to introduce physiognomy as a science, there was not much scientific evidence in his writings. Instead he offered “universal axioms and incontestible principles.” Here are some of the axioms: “the forehead to the eyebrows, the mirror of intelligence; the cheeks and the nose form the seat of the moral life; and the mouth and chin aptly represent the animal life.” The “evidence” came from counterfactual statements peppered with what now would be considered blatantly racist beliefs: “who could have the temerity to maintain, that Newton or Leibnitz might resemble one born an idiot” or have “a misshapen brain like that of Laplander” or “a head resembling that of an Esquimaux.”

The other kind of “evidence” came from the many illustrations, which served as Rorschach’s inkblots on which Lavater (and his readers) could project their knowledge and biases. The knowledge projection came from describing famous personalities. Analyzing the profile of Julius Caesar, Lavater noted that “it is certain that every man of the smallest judgment, unless he contradict his internal feeling, will acknowledge, that, in the form of that face, in the contour of the parts, and the relation which they have to one another, they discover the superior man.” Analyzing the profile of Moses ...