![]()

PART I

Origins

(c. 2000 BCE–70 CE)

![]()

1

Deserts, Tribes and Empires

At the end of the first century CE Josephus looked back with pride on the antiquity of his people and the remarkable accuracy of the Hebrew records in which their history was preserved. It was true that much of this history had escaped the notice of the non-Jewish world, and that Greek writers had paid regrettably little attention to the Jews, but this could be remedied. Before composing the account of Jewish theology in Against Apion, Josephus set out for gentiles a continuous narrative of Jewish history from the beginning to his own day. His twenty books of Jewish Antiquities may have been the first such narrative ever written.1

Josephus was writing under the burden of a national trauma. Born in 37 CE into an aristocratic family in Jerusalem, he had served as a priest in the Temple as a young man before being caught up in 66 CE as a rebel leader in the political struggle against the imperial power of Rome which led, in 70 CE, to the destruction of the Temple. He had been captured by the Romans in 67 CE, but in recognition of a prophecy he was said to have made to the Roman general Vespasian that he would become emperor, he was granted his freedom when the prophecy came true. He composed all his writings on the fringes of the imperial court in Rome, where he seems to have made it his life’s mission to persuade a sceptical Roman populace that the Jews who had just succumbed to the might of Rome were in fact a great people with a long history well worthy of the attention of their conquerors and the wider non-Jewish world.2

For those readers of this book who know the Hebrew Bible, which for Christians constitutes the Old Testament, the first half of Josephus’ Jewish Antiquities will be both familiar and, on occasion, disconcerting. The Bible is full of stories about the Jewish past, but these stories are not always easy to reconcile with non-biblical evidence. Reconstructing the history of Israel in the biblical period was as difficult in the first century CE as it is now. Josephus followed the biblical account for the first ten books of his history, but with additions and omissions which reflected how the Bible was being read in his own day. His narrative is impressively coherent and often vivid, and I shall allow it to speak for itself. He was immensely proud of the authenticity of his history, but for us the significance of his version lies not in its accuracy (which can often be doubted) but in its claim to accuracy. We shall see that the Jews’ understanding of their national history has played a major role in the development of their ideas and practices. Josephus provides our earliest full testimony to this historical understanding. We shall find reasons to doubt the reliability of some of the traditions he transmitted, and at the end of this chapter I shall venture some tentative proposals about what may really have happened, and when, but all religions have stories about their origins, and for the creation of the historical myths on which Judaism has been founded, what really happened matters much less than what Jews believed had happened. And for this, the best witness, writing soon after the completion of the Bible, was Josephus.

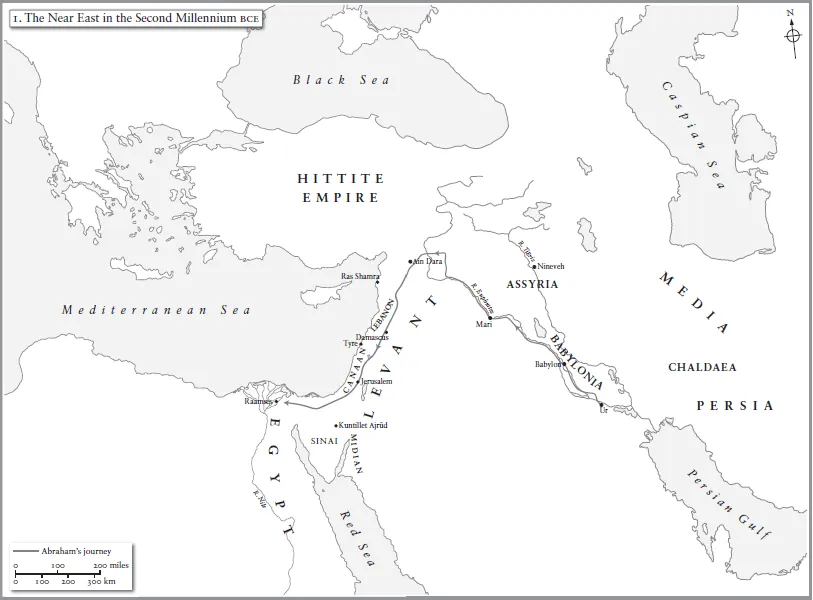

Josephus began his narrative by telling his readers about ‘our lawgiver Moses’, on whose wisdom (as enshrined in the biblical text) almost everything in that history, so Josephus claimed, depends. Hence Jewish history for Josephus started where the Bible starts, with what Moses had said about the creation of the world and humanity, and the separation of the nations after the flood in the time of Noah. Josephus had already filled half the first book of the Jewish Antiquities with world history before he even began to speak of the ‘Hebrews’ and the genealogy of Abraham, but the reader was left in no doubt about the importance of Abraham, who was ‘the first boldly to declare that God, the creator of the universe, is one’, nor his significance for the story of the Jews to follow. Abraham, wrote Josephus, was originally an inhabitant of the city called Ur of the Chaldees, but his religious ideas aroused hostility among the Chaldaeans and the other people of Mesopotamia and he emigrated to the land of Canaan. There, apart from a brief period in Egypt to escape the impact of famine in Canaan, he remained until his death at the age of 175. He was buried beside his wife Sarah, in Hebron, where his son Isaac was also to be buried in the ancestral tomb.3

Josephus proceeds to tell at length the fortunes of some of Abraham’s descendants in Egypt after Joseph, Isaac’s grandson, was taken there as a slave but was raised by Pharaoh to a position of exceptional authority because of his facility in the interpretation of dreams. Joseph provided a refuge in Egypt for his father Jacob and his many brothers when they and their flocks were forced by famine to move south from Canaan in search of food. The family settled happily in Egypt, but Josephus is at pains to note that Jacob prophesied on his deathbed that his descendants would all find habitations in Canaan in due course and that the bones of both Jacob and all his sons, including in due course Joseph, would eventually be buried back in the family sepulchre in Hebron.4

The second half of Book 2 of Josephus’ Antiquities turns to the story of the eventual mass exodus of Jacob’s descendants from Egypt after the Egyptians grew envious of the prosperity of the Hebrews – a name for the ancestors of the Jews first used here in Josephus’ narrative, and followed in the next sentence by a reference to the same people as ‘the race of the Israelites’. The division of the people into tribes (named after the sons of Jacob and, in the case of the half-tribes Ephraim and Manasseh, his grandsons) is explained by Josephus as the will of Jacob shortly before his death, when he ‘charged his own sons to reckon among their number Joseph’s sons, Ephraim and Manasseh, and to let them share in the division of Canaan’ as requital for Joseph’s exceptional generosity to his brothers.

The Hebrews, wrote Josephus, were subjected to 400 years of hardship before they were rescued under the leadership of Moses, son of Amram, ‘a Hebrew of noble birth’, who, with his brother Aaron, led them out of Egypt and through the wilderness towards Canaan. Moses himself, despite his forty years in the desert, including the dramatic revelation on Mount Sinai when he received the laws from God and gave them to his people, was not to reach their destination. His final days were shrouded in mystery: ‘A cloud of a sudden descended upon him and he disappeared in a ravine. But he has written of himself in the sacred books that he died, for fear lest they should venture to say that by reason of his surpassing virtue he has gone back to the Deity.’ The gentile reader of this history, already at the end of the fourth book of this long work (and one-fifth of the way through the whole account), might reasonably have felt a bit puzzled by some aspects of the story up to now, not least the failure of Josephus to refer to any of his protagonists as Jews despite his assertion in his introduction that he would show ‘who the Jews are from the beginning’. The story recounted in Book 1 about the naming of Jacob as ‘Israel’ by an angel did not even explain his use of the same name, ‘Israel’, for Jews generally.5

The next part of the national story fell into a pattern more familiar for Josephus’ readers in a work of history, since the narrative turned to war and politics. The Hebrews, he said, had fought a series of campaigns under the command of Joshua against the Canaanites, some of whom were terrifying giants ‘in no wise like to the rest of mankind’, whose ‘bones are shown to this day, bearing no resemblance to any that have come within man’s ken’. The conquered land was parcelled out among the Hebrew nation, but agricultural success bred wealth, which in turn led to voluptuousness and neglect of the laws which Moses had transmitted to them. Divine punishment for such impiety took the form of disastrous civil wars, followed by subjection to foreigners (Assyrians, Moabites, Amalekites, Philistines) and the heroic efforts of a series of judges, granted power by the people both to rule and to lead them in battle against their enemies. In due course the people demanded kings as military leaders, and the judge Samuel, who had been divinely chosen at birth to lead the nation and had been a prophet with direct guidance from God since the age of eleven, in his old age reluctantly appointed Saul as the first king of the Jews, with a mission (amply fulfilled) to fight the neighbouring peoples.6

At this stage in his narrative, Josephus traces the fortunes of the people – designated as Jews, Israelites and Hebrews, apparently at random – in a series of local wars. The Amalekites, a hereditary enemy whose extirpation had been divinely ordained, continued to harass Israel because Saul was insufficiently ruthless, wishing to spare Agag, the Amalekite king, ‘out of admiration for his beauty and stature’. More insistently dangerous opposition came from the Philistines, against whom the Hebrews fought a series of campaigns in the course of which a new king David made his name as a warrior, having been selected by God to receive the kingdom as a prize not ‘for comeliness of body, but for virtue of soul … piety, justice, fortitude and obedience’. He had already been anointed secretly by Samuel while still a shepherd boy.7

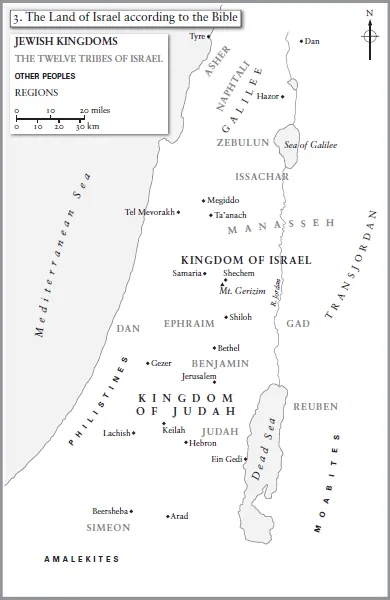

When Saul died in battle against the Amalekites, David at first composed laments and eulogies for the dead king and his son Jonathan; these elegies, Josephus notes, ‘have survived to my own time’. David was informed by God through a prophet in what city he should rule over ‘the tribe called Judah’ and was told to settle in Hebron, while the rest of the country was ruled by a surviving son of Saul. But the result was civil war, which lasted many years until Saul’s son was murdered by the sons of his own followers and ‘all the principal men of the people of the Hebrews, the captains of thousands and their leaders’, came to Hebron and offered their loyalty to David, as the king chosen by God to save the Hebrews’ country by conquering the Philistines. With a large combined force of troops from all the tribes and half-tribes (Judah, Simeon, Levi, Benjamin, Ephraim, Manasseh, Issachar, Zebulun, Naphtali, Dan and Asher, and Reuben and Gad from across the Jordan), David feasted in Hebron to celebrate his confirmation as king and marched on Jerusalem. Jerusalem was inhabited at this time by Jebusites ‘of the Canaanitic race’. No reason is given by Josephus for the assault, but once David had conquered the citadel and rebuilt Jerusalem he named it ‘City of David’ and chose it as his royal residence. Five hundred and fifteen years had elapsed between the original conquest of Canaan by Joshua and the capture of Jerusalem by David.8

Josephus described at length the great victories of David against the Philistines and then the subjection to his rule of the surrounding nations. They were forced to pay tribute to him, so that he amassed ‘such wealth as no other king, whether of the Hebrews or other nations, ever did’. On his death there was buried with him in Jerusalem so much money that 1,300 years later a Jewish high priest raided one of the chambers in David’s tomb in order to buy off a besieging army. Many years after that (just a century before Josephus was writing), King Herod opened up another chamber and extracted another large sum.9 Despite his earlier claims about the unequalled wealth of David, Josephus asserted, illogically, that it was exceeded by his son and successor Solomon, whose wisdom far surpassed even that of the Egyptians. Undistracted by the continuous warfare which had preoccupied his father, Solomon built in Jerusalem the great temple for God which David had planned but not started. Copies of the letters written by Solomon to Hiram, king of Tyre, to request help in acquiring cedars of Lebanon for the purpose in return for grain could still be found in the public archives in Tyre – as anyone could discover, Josephus said, by enquiry with the relevant public officials. Solomon ruled for eighty years, having come to the throne at the age of fourteen, but the glories of his reign were not to last after his death, when his realm was split into two. Rehoboam, Solomon’s son, was ruler only of the tribes of Judah and Benjamin in the south, in the region of Jerusalem, while the Israelites in the north, with their capital in Shechem, established their own centres for sacrificial worship in Bethel and Dan, with different religious practices, to avoid having to go to Jerusalem, ‘the city of our enemies’, to worship. To this innovation Josephus ascribed ‘the beginning of the Hebrews’ misfortunes which led to them being defeated in war by other races and to their falling captive’ – even though he admits that the degeneracy of Rehoboam and his subjects in Jerusalem itself invited divine punishment.10

The initial agent of divine vengeance was Shishak, king of Egypt, and the history of the following generations of the Hebrew kings is punctuated in Josephus’ account by the interventions of great empires (Egypt, Assyria and Babylonia) as well as of the lesser powers of the region, especially the kings of Syria and Damascus, and by civil war between the kings in Jerusalem and the kings of the Israelites with their new capital in Samaria to the north. The fate of the kingdom of the Israelites was sealed when the king of Assyria learned that the king of Israel had attempted to make an alliance with Egypt to oppose Assyrian expansion. After a siege of three years, the city of Samaria was taken by storm and all the ten tribes which inhabited it were transported to Media and Persia. Foreigners were imported to take possession of the land from which the Israelites had been expelled. Josephus, the Jerusalem priest, shows no sympathy: it was a just punishment for their violation of the laws and rebellion against the dynasty of David. The imported foreigners, ‘called “Cuthim” in the Hebrew tongue and “Samaritans” by the Greeks’, adopted the worship of the Most High God who was revered by the Jews.11

In contrast to Samaria, Jerusalem was preserved at this time against Assyrian attack by the piety of its king Hezekiah. But Jerusalem too was eventually to fall victim to the overwhelming military might of a great empire. Trapped between the expansionary ambitions of the Babylonians, the successor empire to the Assyrians, and the power of Egypt to the south, a series of kings in Jerusalem tried to play one side against the other, but ultimately failed to ensure security. After a horrific siege of Jerusalem, King Sacchias (called Zedekiah in the Bible) was captured, blinded and taken off to Babylon by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar. The Temple and palace in Jerusalem were razed to the ground, and the people were transplanted to Babylonia, leaving all of Judaea and Jerusalem deserted for seventy years.12

Josephus did not have much to inform his readers about the fortunes of the Jews in Babylonia beyond the accurate prophecy of Daniel, first in the court of Nebuchadnezzar and then – many years later, when Babylon was under siege by Cyrus, king of Persia, and Darius, king of Media – in the court of Belshazzar. Daniel correctly interpreted the meaning of obscure words which had appeared on the wall of the dining hall in the midst of a feast. The words signified that God would break up the kingdom of Babylon between the Medes and the Persians. Daniel became a great figure in the court of Darius and built at Ecbatana in Media a fortress ‘which was a very beautiful work and wonderfully made, and remains and is preserved to this day … In this fortress they bury the kings of Media, Persia and Parthia even now, and the person to whose care it is entrusted is a Jewish priest; and this custom is observed to this very day.’13

In the first year of the reign of Cyrus, Josephus tells his readers, the king was inspired by an ancient prophecy which he read in the book of Isaiah (which had been composed 210 years earlier) to restore the Jewish exiles to their land:

Thus says King Cyrus. Since the Most High God has appointed me king of the habitable world, I am persuaded that he is the god whom the Israelite nation worships, for he foretold my name through the prophets and that I should build his temple in Jerusalem in the land of Judaea.

The king summoned to him the most distinguished Jews in Babylon and gave them leave to go to Jerusalem to rebuild the Temple, promising financial support from his governors in the region of Judaea. Many Jews preferred to stay in Babylon to avoid losing their possessions. But some returned to Judaea, only to find the process of reconstruction hampered by the surrounding nations, and especially by the Cuthaeans who had been settled in Samaria by the Assyrians when the ten tribes were deported many years earlier. The Cuthaeans bribed the local satraps to hinder the Jews in rebuilding their city and temple. Such opposition was so successful that Cyrus’ son Cambyses, who was ‘naturally wicked’, gave explicit instructions that the Jews should be forbidden to rebuild their city. But then a revolution in Persia brought to power a new dynasty, whose first ruler, Darius, had long been a friend of Zerubbabel, the governor of the Jewish captives in Persia and one of the king’s bodyguards. Zerubbabel used his influence to remind Darius that he had once vowed, before he became king, that if he obtained the throne he would reconstruct the Temple of God in Jerusalem and restore the Temple vessels which Nebuchadnezzar had taken as spoil to Babylon.14

And so the Temple was indeed rebuilt, and became the c...