![]()

Chapter 1

An Introduction and Overview of Infanticide

Infanticide has a lengthy history reaching back to ancient societies (Knight, 1991). In many instances, it was the result of socially sanctioned religious sacrifice, economy to ensure the survival of existing family members, or disposal of physically defective infants (deMause, 1988; Dorne, 1989; Newman, 1978; Radbill, 1987). This practice was common in ancient Greece, Rome, and early German society. During the Middle Ages, infanticide was occurring in every country in Europe (deMause, 1988). Often the practice of female infanticide was condoned as a form of population control. For example, China is a nation well known for the commission of infanticide by their citizenry. In China, it has been estimated that tens of thousands of female infants were murdered due to the cultural beliefs that sons bestow blessings on the family and that females are economic liabilities due to dowries and their departure from the home and extended family care when they marry. But more notorious, and a possibly bigger cause of female infanticide, has been the government’s one-child policy instituted in 1979 but officially revoked in 2013 (Zhu, 2003). This policy was designed to curtail the untenable population growth of the past few decades. The intent of the policy is to reduce births by rewarding families for limiting family size to one child. It interacted with the cultural beliefs regarding the rewards of a son and the costs of a daughter to create a serious infanticide trend of eliminate female babies. The effects of the policy lasted through 2015 as the Chinese government had to reeducate citizens toward different cultural beliefs to stop female infanticide.

This history attributes causes of infanticide to the social forces of government policy, economic, need and cultural expectations. In this book, I explain how two of these social forces – economic need and cultural expectations – persist in modern-day maternal infanticide. I begin by introducing and defining infanticide, discussing the debate whether maternal love and "instinct" are natural or social forces, and describing the nature and trends of the occurrence of infanticide. I conclude with a brief discussion of mental illness as a cause of infanticide, which is beyond the scope of this book.

In this chapter, I introduce and define infanticide, discuss the debate whether maternal love and “instinct” are natural or social forces, describe the nature and trends of its occurrence, and conclude with a discussion of mental illness, which is beyond the scope of this book. The medical community defines “infant” as 12 months and countries with infanticide laws default to the medical community. In the United States, there are no infanticide laws to legally define but use of the term in the legal community generally refers to 12 months. In historical and literary works, an “infant” is a physically, cognitively, and emotionally underdeveloped being. My original work on this phenomenon (Smithey, 1994) developed a sociological perspective on mother-perpetrated infanticide in which I argue that post-partum psychosis and other forms of mental illness do not sufficiently explain most cases of infanticide and that cultural expectations and social inequalities are more powerful explanations. Within this analytical frame, I used the more literary inclusive definition of infanticide by broadening the possibility of infanticide of children from ages 1 day to 36 months. This age range was determined by the potential for post-partum hormone fluctuations lasting up to 36 months (with most causes resolving within 24 months). That research, subsequent research by myself, and published works by others inform this book (Adinkrah, 2001; Alder & Baker, 1997; Arnot, 1994; Briggs & Mantini-Briggs, 2000; d’Orban, 1979; Friedman, Horwitz, & Resnick, 2005; Jackson, 2002; Mugavin, 2005; Oberman, 2003; Oberman & Meyer, 2001, 2008; Rodriguez & Smithey, 1999; Rose, 1986; Scott, 1973; Smithey, 1994, 1998; Smithey & Ramirez, 2004; Stroud, 2008; and others).

The scope of this book is the commission of lethal assault of a child under three years of age by the biological mother. It does not cover the death of an infant less than 24 hours (i.e., neonaticide) because my theory assumes the mother intended to keep and raise the child. I exclude officially diagnosed clinical cases of mental illness that clearly precede the conception of the infant. I omit these cases in an attempt to focus solely on social factors. I exclude clinical cases of post-partum depression and psychosis. These disorders are caused by hormonal imbalances as the mother’s body attempts to readjust to prepregnancy hormone levels (Daniel & Lessow, 1964). I do not include murder-suicide, although social forces causing suicide have been studied at least since Durkheim (1879), maybe before, it is difficult in fatalistic suicide cases to separate fully clinical mental forces from social causes for each and every case. The use of second-hand data is problematic for establishing valid, temporal order. The research on this type of infanticide (e.g., Alder & Baker, 1997) points to overwhelmingly hopelessness and depression as the cause of the murder. The interactions of these causes are valid and require a different, complex theory and analysis than I have done. Finally, I do not attempt to explain infanticide by other perpetrators in this book. I have begun collecting studies, court manuscripts, and qualitative interview data with biological fathers, stepfathers, and mother’s boyfriends who have committed infanticide. That work is in progress.

1.1. Maternal Love: Instinctual or Cultural?

The relative ease with which mothers have been able to murder their children in the past is a function of their ability to emotionally distance themselves from the child. Immediately upon birth, most infants were drowned or left to die from exposure seemingly without serious trauma to the parents. Sociohistorical researchers often view this as a lack of maternal love. For example, Shorter (1975) argues that mothers did not have “maternal love” for their infants. He argues that it developed in the last quarter of the eighteenth century and, in some social classes, even later. He attributes its development and high-priority emotional status of mothers to modernization.

Good mothering is an invention of modernization. In traditional society, mothers viewed the development and happiness of infants younger than two with indifference. In modern society, they place the welfare of their small children above all else. (p. 168)

He further states that traditional mothers did not see their infants as human beings. Parents were not able to emotionally empathize with the infant. The emergence of maternal love occurred only when mothers reordered their priorities, primarily due to romantic love unseating arranged marriages, and put the welfare of the infant above “material circumstances and community attitudes (that forced them) to subordinate infant welfare to other objectives, such as keeping the farm going or helping their husbands weave cloth” (p. 169).

deMause (1988) asserts the “natural” attachment, that is, maternal instinct, modern mothers have to their babies is not natural instinct but rather is based on a psychohistorical change in perception and the lack of a need for distancing. Wall (2001) similarly argues, “Cultural understandings of maternal instinct and love are connected to the popular and scientific notions of attachment and bonding” (p. 10). Birth control practices have gradually become more effective and acceptable in the religious sphere thus reducing the economic and population strain placed on many families and societies and the possibility of infanticide has for those purposes has lessened. However, modern maternal attachment, empathy, and effective birth control have not totally eradicated infanticide.

The occurrence of infanticide has had a significant, enduring trend that in the past century has declined due to advances in understanding and controlling human reproduction. That infanticide continues to occur has not changed. What has changed, and perhaps is new, are the cultural acceptance, beliefs, and social conditions under which it occurs.

Cultural changes have led to the belief that “child homicide” is “the antithesis of usual responses to childhood, quintessentially the time of nurture and development, of vulnerability and dependence” (Stroud, 2008, p. 482). However, the assumed sanctity of maternal instinct remains unquestioned despite history not necessarily supporting it. In fact, the belief is a prominent force used when judging or questioning how much a mother loves her child. Complete and total bonding with the baby at birth is presumed to be automatic and mothers who do not totally sacrifice all they have from that day forward are judged negatively and possibly labeled “bad mother” overall.

I contend, as do other family researchers (e.g., Badinter, 1978; Hays, 1996; Kitzinger, 1989; Oakley, 1974) and historians (deMause, 1988; Shorter, 1975) that maternal love is not automatic and is a social construct that is not founded in nature. Social forces are just as, or possibly more, powerful over individuals as natural forces. Suicide, whether fatalistic or altruistic (Durkheim, 1897), is a prime example of social forces overpowering the natural force of survival. But regardless of whether maternal love is founded in nature or is socially constructed, the expectation is the same – mothers are expected to fully love their children and place all else above them. Girls are gender socialized into this expectation and it is the foundation of modern mothering ideology. Infanticide is the most egregious mother norm violation possible in modern society. The seriousness of the maternal love norm makes understanding infanticide in modern society important for many reasons. Besides the obvious need to prevent the deaths of children, understanding infanticide and the social construction of “good mothering” is essential to understanding women’s economic and cultural inequality that is institutionalized by this belief. Men are not held to this level of sacrifice for their children. This difference upholds patriarchy and the subordination of women, especially mothers.

This work on infanticide contributes to our understanding of mother–infant interactions in several ways. One, I connect the unrealistic, disorganized state of the mothering ideology to the direct consequence of a breakdown in mother–infant interactions – the death of the infant. Two, I make salient the impact of the content of “good mothering” expectations on mothers. This largely untested content comprises the mothering ideology and is promoted by the capitalistic enterprise of the child-rearing industry and the media. Three, I connect family violence and intimate partner violence to infanticide – another facet of the cycle of violence. Four, I expose yet another negative consequence of gender economic and cultural inequality. The valid and large amount of research and data on these inequalities experienced by females has not been incorporated into mainstream criminology to explain female-perpetrated infanticide. Extant research on poverty and violence toward children shows that criminology has high potential for understanding this type of crime (Jensen, 2001) but it must embrace also the cultural and social inequalities of mothering. Generally, mainstream criminology fails to address gendered economic hardship despite feminist research showing that women are more likely to experience fewer economic resources and experience higher rates of poverty than men (Bianchi, 2000). The inability to provide for basic needs produces stress and frustration that creates a demoralizing environment potentially resulting in aggression (Messner & Rosenfeld, 1997). Five, I provide a detailed view of the effects of stress on women and offer that these stressors operate as a range from the “normal” stress to “dangerous” stress of childrearing. I suggest that any mother could commit violence toward her baby. Placing normal people in abnormal circumstances can lead to violence, especially mothers experiencing a significant lack of economic resources. Six, I bring to light a dire consequence of socially coercing and forcing women to raise unplanned, unwanted babies. Finally, I provide windows to opportunities for preventing violence against children, including nonlethal violence.

1.2. Trends: How Often Does Maternal Love Go Wrong?

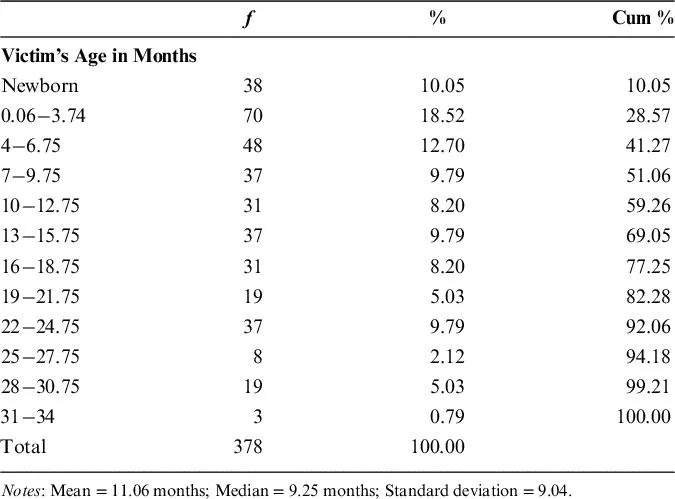

Several studies find that infants under the age of 12 months have a higher risk of homicide than children of other ages (Abel, 1986; McCleary & Chew, 2002; Overpeck, 2003; Rodriguez & Smithey, 1999). In fact, the first 24 hours of life carries a risk of homicide that is comparable to homicide rates of adolescents (FBI Uniform Crime Report, 2015) and is more than twice the national incidence (Crandall, Chiu, & Sheehan, 2006). I collected demographic data on 380 cases of infanticide for the years 1985 through 1990 in Texas (Smithey, 1994, 1998) and find that newborns have the highest risk of lethal injury (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1. Distribution of Infanticide Victims’ Ages in Texas, l985–1990.

Studying official data in the United Kingdom, Brookman and Nolan (2006) find that of the children killed between 1995 and 2002, more than one-third was under the age of 12 months.

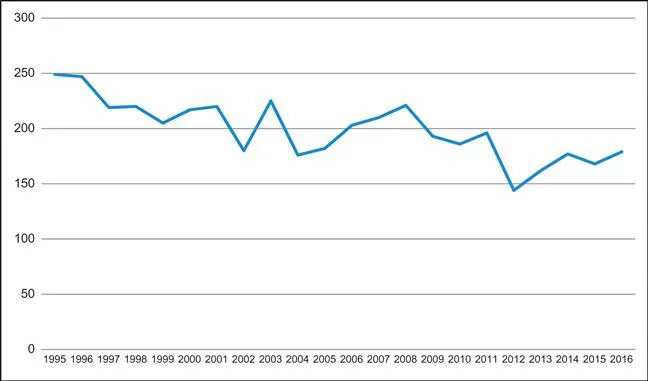

Official crime data show that infant homicide has declined in the United States. Figure 1.1 shows a 54% decline the number of infants less than 12 months of age murdered over the past two decades. It must be noted, however, that this is the smallest age interval given in the official crime data. All other age intervals range from 4 to 10 years. Considering proportionality of the interval, Craig’s (2004) finding that “the risk of becoming the victim of homicide is much greater for infants than another age group” (p. 57) still holds.

Figure 1.1. Number of Homicide Victims in the US < One Year of Age. Source: FBI Crime in the United States, 1995–2016.

Children are more likely to be killed by their parent than by a stranger or other type of offender (Schwartz & Isser, 2007) and mothers are the most likely offenders (Smithey, 1998). Brookman and Nolan (2006) find that when the perpetrator is female, there is a 90% chance it is the mother (p. 873). However, biological fathers and stepfathers combined make up only 83% of male perpetrators. In my research, mothers are the likely offenders until age four months, when fathers became the likely offenders until six months, then a combination of mothers, fathers, stepfathers, and mother’s boyfriends became almost equally likely to the offender until age 25 months. At that age and until age 32 months, mothers were the most likely offender (Smithey, 1994, 1998). Overall, the studies find that mothers are the most likely offender of filicides less than three years of age.

The chances of infanticide are higher for babies that are atypically ill or “colicky.” Colic occurs in up to 28% of infants across all categories of gender, race, and social class (Gottesman, 2007, p. 334). Studying mothers of colicky infants, Levitzky and Cooper (2001) find that 70% of mothers of colicky infants had explicit aggressive thoughts toward their infants and 26% of these mothers had infanticidal thoughts during the infant’s episodes of colic (p. 117).

The studies on whether male or female infants are at greater risk of infanticide have produced mixed results. Some studies find no significant differences in whether the victim is male or female (Chew, McCleary, Lew, & Wang, 1999; Smithey, 1999). Brookman and Nolan (2006) conclude the gender of the victim varies by the gender of the offender with female-perpetrated infanticide not being victim-gendered but male-perpetrated infanticide tends to happen to male infants. Earlier research by Overpeck (2003) reports a slight favoring of male victims by 10% but this includes male and female offenders. Just 10 years prior, Abel (1986...