![]()

Chapter 1

The Puritan Assault on Drink and Taverns

At the time of the Great Migration of Puritan colonists to America in the 1630s, the consumption of drink at taverns had long been entwined with public gatherings in English society. In New England echoes of these traditions rever-berated on various public occasions, as Massachusetts colonists regularly converged on public houses to meet and conduct civic affairs in the seventeenth century On some occasions the voters of an entire town might assemble in these familiar rooms to transact town business. Still more august assemblies convened in taverns in public pomp and ceremony when selected taverns hosted meetings of the courts. In public rooms, the justices presided over the adjudication of offenses ranging from unpaid debts to murder, and on such days taverns could be the settings in which the most fundamental values of Massachusetts society were exhibited and reaffirmed. Here the hierarchy of governors from king to constable was announced, upheld, and made partially visible; here the “best men” at the top of the social hierarchy sat in judgment of the people called to court; here those who had violated the order and harmony of community life were condemned and humiliated.1 On such days colonists witnessed and acted in a vital tableau of community life, a physical assembly integrated in part through the sale and exchange of drink.

Yet the generous drafts of liquor consumed at these and other assemblies had also become a source of contention. A transformation in public life was under way. In the seventeenth century the habitual use of drink in taverns came under severe censure and greater regulation. In first Old and then New England, Puritan leaders became the most vocal critics of customary drinking habits. Their vision of a godly commonwealth owed much to tradition, revering as it did the principles of hierarchy and consensus in community life. But they simultaneously sought to establish a reformation in public and private behavior by compelling conformity to the nascent modern value of temperance.

This was not just an attack on idleness and dissipation. At the time of the Puritan migration, public houses had come to be viewed as potential sources of challenge to England’s ruling hierarchy. Such houses had multiplied dramatically in previous decades, and many harbored growing numbers of the transient and unemployed poor with no secure place in the social hierarchy. The mounting concern for the preservation of order through the enforcement of temperance informed the establishment of New England. By the end of the century the officers of the courts who convened in taverns had become responsible for the enforcement of a number of drink regulations and laws. Taverns continued to be indispensable gathering places in Massachusetts towns, but Puritan leaders were determined to purge many of the customary uses of them from community life.

I

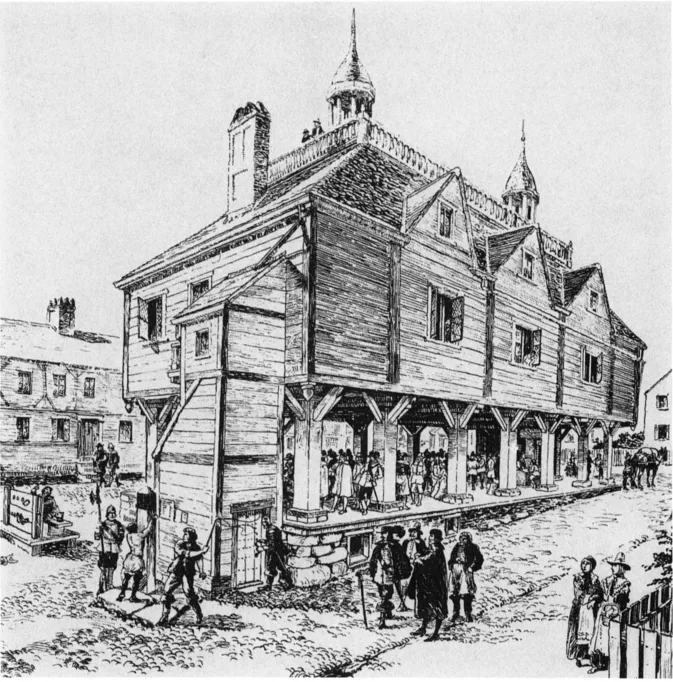

The character of public life in Massachusetts taverns is not easy to unveil, but the diary of Superior Court justice Samuel Sewall between 1674 and 1729 provides glimpses of court meetings and other official gatherings in taverns in Boston and other towns. The settings for the courts were modest. Few communities possessed buildings designed to host civic functions, and none of these buildings exceeded the size of a substantial house, public or private. Deputies to the General Court (more commonly called the Assembly after 1691) and the governor’s Council gathered in Boston’s Town House in the seventeenth century, a simple wooden structure built in 1657 with an open ground floor used for a market and chambers above. As a member of the Council, Sewall most often attended meetings in the Town House chambers. Nearby taverns, however, appear to have been the favored site for court sessions. In 1690, for example, Sewall and other justices decided the guardianship of the son of an Indian sachem at a session held in George Monk’s Blue Anchor Tavern. Monk hosted so many sessions of this and other courts that the appraisers of his estate in 1698 designated one chamber of his tavern as the “court chamber.” Before Monk, John Turner had kept tavern for the courts in Boston.2

In Salem, Charlestown, Cambridge, and other county seats, the courts also assembled in taverns. At Charlestown in 1700 the justices of the Superior Court heard cases in “Sommer’s great room below stairs” until seven at night. The court once convened at a Cambridge meetinghouse only because the town house was situated too near a house with smallpox, and tavernkeeper Sharp—also afraid of the disease—refused “to let us have his chamber.” All five of those licensed in Salem in 1681 became obliged to “provide for the accommodation of the courts and jurors, likewise all matters of a public concern proper for them.”3 In Massachusetts there continued to exist a close affinity between the provision of drink and public gatherings.

Plate 1. Samuel Sewall. Courtesy, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

Even after the erection of the new and more imposing Boston Town House in 1713, taverns continued to host the courts. Sewall lectured the grand jury at the first session held in the new building, telling them, “You ought to be quickened to your duty” to detect and prosecute crimes because “you have so convenient and august a chamber prepared for you to do it in.” At this very session, however, the court adjourned and reconvened at a nearby tavern. Sewall himself later waited “on the court at the Green Dragon” to testify against a defendant.4 Thus colonists were accustomed to associating taverns with that most paramount of Puritan concerns—the maintenance of law and order—because public rooms were so often the settings where the judicial hierarchy of the province made itself visible and decided cases.

Plate 2. The Town House. Drawn from the original specifications by Charles Lawrence, 1930. Courtesy, the Bostonian Society / Old State House

The ready resort to taverns by court officials undoubtedly owed much to the convenience of heat and light provided by tavernkeepers during the winter against the expense of duplicating these services in town house or meetinghouse. Court sessions—Superior or lesser courts—could last anywhere between a few hours and several days, depending on the docket or the weather. When justices traveled on circuit to Plymouth, Springfield, Salem, or Bristol, they often did not arrive on time or together. In 1707 Sewall reached Plymouth about ten in the morning after a day and a half of travel from Boston, but two other justices did not arrive until six at night, so they “could only adjourn the court.”5 To heat and light the town house or meetinghouse to no effect for such an expanse of time was costly. Tavernkeepers could also provide lodging, food, and drink to justices riding on circuit as well as to their escorts and servants.

It is not clear whether justices consumed alcohol while court was in session. Sewall frowned when tavernkeeper Monk brought in a plate of “fritters” during one session, and was pleased that only one justice ate them. Between sessions, however, justices probably dined in the “court chamber.” In Hampshire County the justices, constables, jurors, and other court officials probably all dined together, since each of their meals cost the same amount in the accounts of tavernkeepers.6 Rather than move back and forth between tavern and town house (if one existed) and duplicate fires and other services in less convenient chambers, Massachusetts judicial officers simply made public houses into their seats of authority.

Taverns could be suitable sites for the administration ofjustice because men of high social rank expected and received deferential posture from ordinary men in any setting, at every occasion of meeting. Though Sewall betrayed a desire for “august” settings for court proceedings, the authority of the court rested much more in the personal status of the individuals who presided over it than in the chambers in which it took place. Social status and hierarchy differentiated members of Massachusetts society in a marked way, far more intricately than the size and scale of public and private houses suggest. The dress, speech, and bearing of individuals readily signaled their status and how they should be addressed. Sewall and fellow justices expected and received expressions and postures of deferential regard not only from people attending the courts but on all other occasions of meeting. When justices traveled to distant towns to convene courts, sheriffs and deputy sheriffs greeted and escorted them not just to ensure their safety but to honor their persons and offices. On Sewall’s way to Springfield in 1698 a guard of twenty men met him at Marlborough and escorted him to Worcester. There a new company from Springfield met him to bring him the rest of the journey. This group saluted the justices with a trumpet as they mounted their horses. Sewall often treated these attendants with food and drink, a gesture symbolic of his own role as protective and nurturing patriarch. In the case of a journey to Plymouth in 1716, he gave the sheriff and deputy sheriffs a dozen copies of one of Increase Mather’s sermons, a more explicit gesture of a Puritan patriarch.7

Such honorific displays were also customary at militia musters meeting outside taverns and at formal state dinners in taverns. At a training dinner at Newbury, “Mr. Tappan, Brewer, Hale, and myself are guarded from the Green to the tavern,” and “Brother Moodey and a party of the troop with a trumpet accompany me to the ferry.” In Boston a processional display often announced a dinner or meeting at a tavern by government officials. In 1697 the Company of Young Merchants treated the governor and Council to food and drink at Monk’s tavern. The company escorted the councillors from the Town House to tavern in formation and after dinner escorted them back, finishing with “three very handsome volleys.”8 While these processions were far less elaborate than analogous English ceremonies, they nevertheless served their purpose by announcing and reinforcing the magistrates’ superior social status, judgment, and authority to those waiting for the court and spectators observing the scene. Such men could command deference in any situation in or out of court and could conduct the most solemn proceedings in any tavern.

Inside a tavern where court was in session, the authority of visiting justices influenced everyone’s behavior. The chambers set aside for the courts in Boston in the 1680s had simple furnishings, but gradations in the furniture enhanced the authority of the presiding magistrates in subtle ways. John Turner’s court chambers contained eleven chairs, presumably for justices and distinguished spectators, and three benches and a stool, where defendants and witnesses probably sat. Four tables made the chamber conducive to dining by the justices between sessions. George Monk accommodated the courts with a chamber containing a dozen leather chairs and one oval and three long tables. There was also a bench, again probably for litigants. Plaintiffs, defendants, and witnesses gathered more indiscriminately in the other public rooms of Turner and Monk. In one of Turner’s front rooms they grouped around three tables and sat on benches. In another there were four tables, three benches, and only two chairs.9 What appears to distinguish the court from other chambers is the number of chairs made available (perhaps considered necessary) for the magistrates who gathered there. When drinkers left the public rooms to enter the court chamber, the eminence of the men seated there, perhaps in a row, invested the room with a gravity absent in other parts of the tavern. On court days in public houses, the hierarchy of governors above and beyond the familiar model of family government became more visible to the people called to or visiting the house to ask for justice or receive punishment from the assembled magistrates.

Sewall’s diary also reveals his personal habits of drink consumption. While he might not have consumed alcohol while hearing cases, he can be glimpsed making use of it on a variety of occasions. He regularly drank wine and cider in his home, when traveling, and at such events as weddings and barn raisings. In 1700 he invited several men he met by chance on Boston Neck into his home to drink. On another occasion he gave “a variety of good drink” to the governor and Council. He brought with him “a jug of Madeira often quarts” to a barn raising and gave a relative in prison eighteen pence “to buy a pint of wine.” When traveling from Sandwich to Plymouth, Sewall dined at one tavern, fed his horse at another, and stopped to “drink at Mills.”10

Sewall also consumed alcohol at funerals. The provision of drink at funerals was customary, even if the deceased was poor. In settling one Boston widow’s estate, the appraisers allowed for payment from the estate for a quart of wine for themselves and seven and a half gallons for the widow’s funeral, despite the fact that the estate could not meet the demands of the creditors, who received only nine shillings and twopence for each pound of debt.11 At such a gathering honoring the deceased, the distribution of drink was considered indispensable. It held more importance than the creditors’ demands on the estate.

Such use of drink and taverns remained within the bounds of temperate behavior in Puritan Massachusetts. At marriages, funerals, and barn raisings as well as court days the purchase, provision, and consumption of alcohol did not disrupt or violate Puritan precepts. Absence from labor was justified, and, if disorder did develop, such as drunkenness or profanity, magistrates or other figures of authority could take steps to quell it. Even the most rabid critics of intemperance admitted the necessity of public houses for the provision of alcohol so necessary for the conduct of social relations as well as the refreshment of travelers. In 1673 Increase Mather allowed that in such “a great Town” as Boston “there is need of such [public] houses, and no sober minister will speak against the licensing of them.” Benjamin Wadsworth, another Boston minister, also conceded that “the keeping of taverns … is not only lawful but also very useful and convenient” for the “accommodating of strangers and travelers.” Town dwellers “may sometimes have real business at taverns” and so may purchase “what drink is proper and needful for their refreshment.”12

Yet, as these statements imply, what magistrates and ministers considered “proper and needful usage” continued to be an issue in Puritan Massachusetts during the first decades of settlement, provoking alarm by the last quarter of the seventeenth century. While Puritan leaders and their constituents continued to gather in taverns for a wide variety of purposes in the 1680s, even for the airing and adjudication of capital offenses, leaders at the same time increased their efforts to control and restrict patronage. A closer inspection of Sewall’s diary reveals a distinct pattern of restricted patronage that exemplifies a model of behavior that clerical and secular leaders sought to impose on the populace as a whole in the seventeenth century.

Although Sewall might have spent hours in a court chamber over several days of court sessions, he rarely visited Boston taverns for other purposes. His diary of daily contacts and conversations between 1674 and 1729, including thousands of entries, shows a very low rate of patronage by any standard of measurement—only thirty-o...