![]()

1 The Great Transformation

1.1 High Stakes

By 2030, the 10 members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the People’s Republic of China (PRC), and India—home to half the world’s population—will be poised to quadruple their output and emerge decisively from a history of poverty. These countries are not alone in attempting such an ambitious leap, but because of their scale, pace of change, and increasing interdependence, they merit attention as a group. If these economies—called ACI in this study—sustain rapid growth, they will dramatically transform the lives of their more than 3 billion people and indeed the global economy. This book looks ahead to the policies required to manage this transformation, notwithstanding shorter-term macroeconomic challenges, because of its immense implications for the ACI economies and the world.

The term “great transformation” is chosen judiciously to describe these developments. It was first applied by the anthropologist Karl Polanyi to the extraordinary social and economic changes brought about by the rise of the market economy in developed countries (Polanyi 1944). The transformation underway in Asia—defined by the spread of highly productive, market-based economic systems across the world’s most populous region—is arguably as important. Polanyi’s insight, that massive economic change has deep implications for governance, is also an important theme of this book. Earlier economic transformations shifted the locus of productive activity and its governance from tribes and feudal estates to cities and nation states. Today’s economic revolution, in turn, is shifting responsibilities to market-based institutions, regulated by governments on the national, regional, and global levels. Once again, the challenge facing governance is what Polanyi called the “double movement” of policy—the promotion of market-based growth on the one hand, and the management of its negative side effects on the other.

There are reasons to be optimistic about the prospects in ACI. Economic theory, old and new, attributes growth to physical and human capital accumulation, economies of scale, innovation, and institutions that support market-driven competition. Most ACI economies possess these attributes and have ample potential for “catching up” with global productivity frontiers. Based on current projections presented in Chapter 2, they will contribute 40% of the world’s savings in 2030 and account for 51% of the growth of the world economy between 2010 and 2030. ACI investments will also dramatically expand the pool of talent and capital engaged in creating knowledge. Information technologies can multiply these gains by facilitating connections among centers of innovation and production. Technologies just over the horizon, spanning physical and biological fields, could further enlarge the economic toolkit of the ACI nations and mitigate constraints on growth.

Yet the risks are also great. The immediate economic outlook is clouded by major macroeconomic challenges. The ACI economies are more resilient than in the past, but the world environment is still dominated by conditions in developed economies. Other risks are associated with rapid development itself: large and wide-ranging institutional innovations will be required to support the transformation of ACI finance, production, and demand. Many promising economies have tripped up in attempting to move beyond middle-income levels in a short time frame. The drivers of growth cannot shift smoothly across different stages of development unless the institutional setting for new, more advanced stages is established and tested in advance. Still other risks are related to the sheer scale of ACI growth, which will push demand for energy and raw materials beyond levels experienced in the past. This could also severely harm the environment.

The combination of great opportunities and risks makes the stakes in ACI’s development unusually large. As Asia 2050: Realizing the Asian Century argued, the “Asian Century” is not foreordained (Kohli, Sharma, and Sood 2011). The success of the ACI economies is essential to the world’s future and the risks warrant careful analysis. The great transformation depends on the efforts and decisions of billions of people, but it will require skillful guidance from governments at many levels. Much has been learned from economies that made the transition successfully, including in Asia, and distilling lessons for policy is one of the objectives of this book.

1.2 Powerful Headwinds

As this study goes to press in 2014, the ACI economies face an uneven global economic environment. Five years after the start of the 2008–2009 global financial crisis—the most severe that the world economy has experienced in seven decades—there are signs of recovery, albeit unevenly spread. The massive financial deleveraging that sparked the crisis in the United States (US) has led to multiple aftershocks. Households and firms in many countries reduced expenditures while governments turned to debt-financed spending to sustain activity. At this writing, Europe continues to resolve sovereign debt problems—it is evident that it will not be solved without major adjustments in the financial and budgetary structure of the European Union. In the meantime, high unemployment persists in many countries, financial markets remain volatile, major financial institutions are fragile, and debt burdens are rising in Japan and the US. Growth is uneven even in emerging economies that initially helped drive the recovery. Cooperation among countries has proved difficult and further financial shocks may follow. Many governments now also face political tensions—fueled by the prolonged slowdown—that makes decision-making highly difficult.

Will these global developments adversely affect the ACI economies? The answer is almost certainly yes. The region withstood the early stages of the crisis well, thanks to strong initial fiscal positions and low levels of financial leverage and debt. The ACI economies did experience early export declines, but then turned to their own demand, including intraregional trade. The drivers of regional demand ranged from the expansion of consumption in Indonesia to infrastructure and residential investment in the PRC. Exports also recovered. Slow global trade growth is taking its toll, and opportunities for further regional stimulus are shrinking.

Given the prospect of lackluster growth, a cyclical deceleration of ACI growth appears probable. ADB (2014) shows that growth in developing Asia slowed from 7.4% in 2011 to 6.1% in 2012 and 6.1% in 2013. Developing Asia’s growth is projected to be 6.2% in 2014 and 6.4% in 2015.1 This “soft landing” is subject to downside risk, and is likely to require effective and nuanced macroeconomic policies, at least when compared to those applied in the recent period when growth rates appeared to have “decoupled” from those of developed economies.

Resilience is a complex mix of policies and economic characteristics. A resilient policy environment requires effective tools for macroeconomic monitoring and management, ample fiscal and foreign exchange reserves, national safety nets for individuals and small firms, and international safety nets for national financial systems. A resilient economic structure requires flexible labor and capital markets and well-regulated financial institutions. These policy and structural characteristics enable countries to manage shocks in less time and at lower cost, and are essential in times of turbulence.

There are two additional reasons for medium-term analysis—for looking beyond the current crisis—even in times of great uncertainty. First, a focus on medium-term prospects can help to identify policies that are useful in the short term and sustain growth beyond the short term. Embracing the opportunities and managing the threats that the ACI region faces will require structural changes with long lead times. Many of those changes must be launched now.

Second, a clear medium-term vision can reduce uncertainty and build confidence, which is in short supply in the current downturn. Rapid growth is possible and indeed likely in Asia, even as it requires shifts in the region’s growth patterns toward its own markets, investment opportunities, and technological capabilities. It will take confidence to drive progress on institutional change, infrastructure needs, and forward-looking private investment. Early initiatives to launch the necessary policies and growth engines will support the transition itself. This is why a map and policy framework for self-fueling growth—to solve the coordination problems that face economic agents in uncertain times—are essential elements of a medium-term growth strategy.

1.3 Dimensions of Transformation

A starting point for analyzing the transformation ahead is a growth path based on “continued convergence”—a baseline projection that extends the development experience of recent decades into the future. These calculations, reported in detail in Chapter 2, assume that the subset of emerging economies that have reduced the productivity gap against developed economies in the past—the members of the so-called “convergence club”—will continue to make progress in the future. Nearly all the ACI economies are such members and others are likely to join them.

Sustaining convergence does not mean that the ACI economies will be immune from global business cycles. It only argues that their trend productivity growth rates will continue to exceed those of advanced countries. The path assumes, however, that the world economy will encounter neither new roadblocks to development nor unexpected positive advances, such as in technology or productivity. Of course, no single projection is likely to be right. This study will therefore analyze deviations from the baseline, due to shocks and policy changes that lead to lower or higher development paths. That analysis is the primary focus of Chapter 2.

The baseline projects ACI output to quadruple by 2030, in essentially one generation. Per capita incomes would triple, and the region’s share of world output would rise from 15% to 28% (in 2010 constant prices as reported in Chapter 2). In that generation, the economy of ACI would become larger than that of the United States or Europe—inheriting new economic opportunities as well as responsibilities in governing the global economy. It has been increasingly observed that the world’s economic center of gravity, after shifting westward for much of the previous millennium, is moving into the middle of the ACI region.2

These are aggregates for a region characterized by great variations in productivity, wealth, resources, culture, and economic structure. Yet because the prospects of the 12 ACI economies are interconnected, all are likely to participate in the region’s progress. The aggregates are inevitably dominated by the PRC and India, which are expected to have average growth rates of 7.0% and 7.6% annually (in 2010 constant prices), respectively. ASEAN is projected to grow at an average rate of 5.4% annually, also a strong rate by most historical standards. Meanwhile, the world’s most developed economies—Japan, Europe, and the US—are likely to have average growth rates annually in the 1%–2% range. Their prospects are dampened by having reached the frontier, and by stable or declining populations and high levels of debt and social expenditures.

The growth of ACI—arguably the world’s most promising growth engine—is thus critical for the world economy and will depend increasingly on the region’s own policies. The implications, both positive and negative, are assessed in four key dimensions of the coming transformation: the quality of life; the structure of production; the management of resources and the environment; and international cooperation.

1.3.1 The quality of life

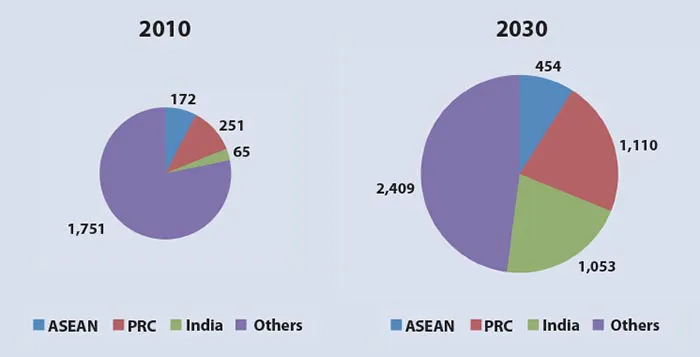

ACI citizens are poised, if not guaranteed, to experience dramatic improvements in their quality of life. The region’s development could eliminate extreme poverty, lift billions into the middle class, and raise incomes for virtually all subregions and social groups. To some extent, these improvements will follow from growth. Chapter 2 shows that under plausible assumptions the number of middle-income consumers in the ACI economies—in this study defined as those with consumption levels between $10 per day and $100 per day in 2005 dollars—will grow to 2.6 billion, representing 72% of the region’s population in 2030. This means that the size of middle-income markets will grow extremely fast: in 2010, the number of middle-income ACI consumers was only 12% of the population (Figure 2.5). ACI will drive the expansion of the world’s middle class: by 2030, half of all middle-class people will live in the ACI economies (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: ACI Will Lead the Expansion of the Global Middle Class (millions of people)

ASEAN = Association of Southeast Asian Nations; PRC = People’s Republic of China.

Source: Authors’ calculations.

The reason these developments are so significant is that middle-income spending can support substantial discretionary expenditures, allowing people to reach living standards comparable to those experienced mainly in developed countries. This has tangible effects. Middle-class consumption does not mean exactly the same in different countries, but it does usually mean improved housing, both in scale and quality, and ubiquitous access to white goods such as refrigerators. Middle-class ACI consumers also enjoy the reasonable luxuries of everyday life—plentiful food, attractive clothing, and digital technology. Most have access to education, health care, and public transport. In many countries, people enjoy the freedom offered by their own motorcycles or automobiles. Middle-class urban neighborhoods may have parks and shopping centers for socializing and entertainment, and typically feature long-distance communications and transport services that allow people to connect with families and friends, wider work opportunities, and new experiences. Even with incomes that are relatively low compared to those in developed countries, the region’s immense absolute demand will provide incentives for products and services tailored to ACI budgets.

These gains will depend in large part on urbanization. On average, cities are more than twice as productive as the areas around them, and their dense populations facilitate the production of a great variety of goods and services at relatively low cost. Between 2010 and 2030, the urban population of the ACI economies is projected to expand by some 700 million people to nearly 2 billion, reaching 40% of the ACI population by that time (UN 2012).

The list of the world’s urban agglomerations will be increasingly dominated by the ACI economies. By 2025, seven of the world’s 15 largest cities will be in ACI. Some of these cities will be immense—New Delhi (33 million), Shanghai (28 million), Mumbai (27 million), and Beijing (23 million). The world’s largest city will be Tokyo (39 million), also in Asia (UN 2012). The PRC alone is projected to have 221 cities with a million or more people (McKinsey Global Institute 2009). Most of these cities will face severe challenges in managing burgeoning growth. But building infrastructure and providing related services for this wave of urbanization is not only a burden; it is also a growth engine. For example, it is estimated that as many new subway systems will need to be built in Asia over the next two decades as exist in the world today, and four times as much office space will have to be added as now exists in Europe (McKinsey Global Institute 2011b). All this sounds futuristic, but it follows from reasonable projections. Moreover, the simulations of Chapter 2 suggest that the broad characteristics of the transformation are similar across alternative scenarios.

Even if the positive projections are realized, rapid market-based growth will not, by itself, guarantee gains for everyone. Nor will it automatically deliver many goods and services that people value and expect. Market forces maximize the pace of growth and reward the nimble: the young, the well educated, those with resources to invest, and those lucky enough to live in ce...