![]()

ONE

The Pursuit of Long-Run Economic Growth in Africa

An Overview of Key Challenges

Haroon Bhorat and Finn Tarp

Historically, the African continent has been largely dismissed as a case of regional economic delinquency, with the levels of growth necessary to reduce poverty and inequality deemed to be consistently unattainable. In the last decade, however, significantly higher levels of economic growth have ushered in a new era to the region, suggesting it may, potentially, serve “as the final growth frontier with the last of the great untapped markets, ripe for rapid growth and development” (Bhorat and others 2015a). Data from The Economist and the International Monetary Fund (2011) support these assertions, as six of the fastest growing economies globally over the period 2001 to 2010 were in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA hereafter): Angola, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Chad, Mozambique, and Rwanda. This volume specifically refers to the following six economics as the African Lions: Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, and South Africa.

The 1980s is often referred to as the continent’s lost decade. The combination of massive external economic shocks; governance failures; under-investment in vital social services; significant macroeconomic imbalances; poor infrastructure; and structural trade deficits (Devarajan and Fengler 2012; Collier and Gunning 1999) undermined the early progress achieved after independence from Africa’s colonial masters. Orthodox stabilization and structural adjustment programs dominated the policy agenda (Tarp 1993, 2001) and stagnation continued well into the 1990s. The post-2000 African economic boom, in contrast, has been built around a composite of factors, including improved macroeconomic policy; high commodity prices; significant improvement in the quality of governance and institutions; technology (mobile phones in particular); demographic growth; urbanization and the rise of new, dynamic African cities; and, in some cases, better targeted social policy. In turn, these factors, regularly supported by substantial inflows of foreign aid (Tarp 2015), have enabled the growth momentum on the continent to be maintained.

Not surprising given where African countries found themselves in the mid-1990s, socioeconomic indicators—poverty, inequality, access to social services, institution development, and infrastructure levels—remain weak in Africa (see Arndt, McKay, and Tarp 2016) and typically lag behind developing nations in other regions of the world. There are also concerns related to the sustainability of recent economic performance and socioeconomic advance for various reasons. First, an important part of this growth has been driven by dependence on extractive resources, which are volatile and subject to exogenous factors. Further, being a capital-intensive sector, there remains limited scope to address the rapidly increasing supply of labor through resource-based development. Second, emerging labor trends indicate that agriculture’s share of employment is diminishing, with the services sector absorbing a significant share of the labor force (Newman and others 2016a). However, due to low human capital levels, the majority of these workers are employed on the fringes of the economy, working mainly in informal low wage and low productivity jobs. The manufacturing sector in most of these countries is shrinking following a considerable decline in manufacturing value added between 1990 and 2000. Third, while inequality is notoriously difficult to capture, it does appear as if inequality indicators are widening through the continent, driven by wage differentials across sectors, differences in human capital levels, and urban and rural splits. Finally, many African countries are at different stages of demographic transition—shifts from a high fertility, high mortality phase to a low fertility, low mortality state—a state associated with dividends that should, ideally, contribute to economic growth and development, which does not, however, seem to be materializing (Oosthuizen 2015).

A BRIEF MACROECONOMIC OVERVIEW

Africa’s postcolonial growth history may be divided into two distinct phases. The first, between 1965 and 1990, was characterized first by progress and then by dismal growth in the 1980s. More recently, growth has surged. This chapter presents a brief overview of key macroeconomic indicators for Africa broadly, and specifically for our sample of six African economies.

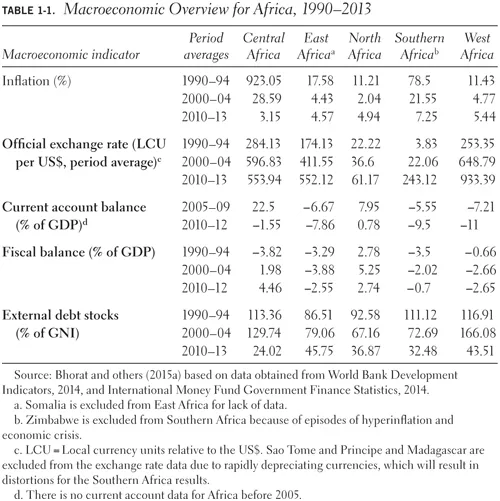

Table 1-1 presents an overview of inflation, exchange rates, and current and fiscal accounts, as well as external debt, for the various African subregions. It is evident that macroeconomic performance has significantly improved across SSA, as demonstrated by inflation, which dropped from exceptionally high rates in 1990–94 to single-digit values in the two subsequent periods.

Over this period, these economic regions experienced slight exchange rate depreciation against the US$, but since then, the exchange rates have stabilized closer, possibly, to their equilibrium value. Despite significant currency depreciations, exports have not increased sufficiently to improve the current account balances. For example, Kenya experienced what has been termed a clogged “exports engine” (World Bank 2014) as the exports of goods as a percent of GDP declined in the period between the mid-2000s and 2014, while imports of goods continued to increase. However, over this period, Kimenyi and others (2015) note that Kenyan services exports continued to expand, although not sufficiently to offset the widening gap between exports and imports. Overall, however, current account deficits within the context of a developing nation do not indicate fiscal imprudence, as external funds (that is, especially aid) often supplement domestic resources.

Although the majority of the current fiscal accounts remain negative, they are within a narrow and sustainable range for the different regions. It is also apparent that external debt has been relatively well managed, as debt to Gross National Income (GNI) levels has fallen steadily since 1990 for all regions of the continent. This is in part due to debt relief, but is also partially a result of various African economies diversifying their output, resulting in a significant proportion of these states financing investment through (fast-expanding) domestic credit markets rather than through external debt.

Growth within the African Lion states was often accompanied with significant welfare gains. In South Africa and Ethiopia, significant welfare gains were observed, as measured by increasing access to social services, improved housing and basic infrastructure, and a reduction in poverty levels. Overall, while table 1-1 paints a positive picture of the state of Africa’s macroeconomic environment, risks arise from political instability, war and conflict, and external shocks such as changes to commodity prices, as well as the spread of disease (Bhorat and others 2015a).

STRUCTURAL ECONOMIC TRANSFORMATION AND INCLUSIVE GROWTH

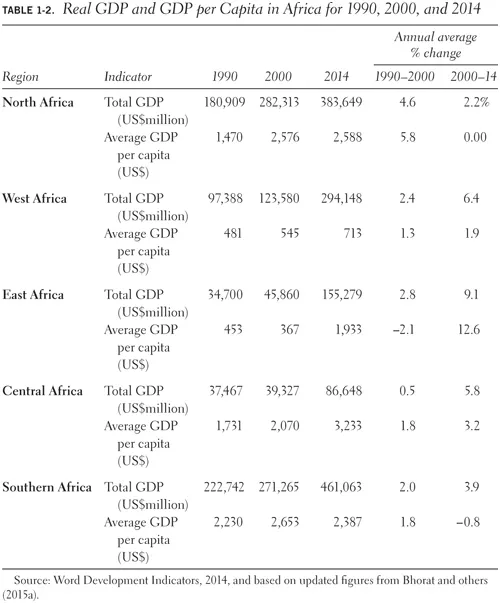

Along with the rapid economic expansion across Africa in the post-2000 period, the continent experienced quickly rising average income levels, as well as shifts in the composition of output of the various economies. Tables 1-2 and 1-3 provide additional insight into these fundamental changes.

Table 1-2 demonstrates that most regions experienced real annual GDP growth exceeding 4 percent over the 2000 to 2014 period, with the exception of Southern Africa, where growth dipped slightly below this threshold. South Africa, the most dominant economy, experienced contractions in overall growth. As already alluded to, growth accelerated relative to the previous decade in all regions, including countries such as Ghana and Mozambique. Lastly, we note an increasing trend in real per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP), except in the North Africa region, which experienced economic and political turmoil following the social upheaval wrought by the Arab Spring.

While these economic indicators are promising, it is necessary to take a closer look to discuss the overall sustainability of Africa’s economic expansion and assess whether this growth translates into the achievement of Africa’s development objectives of equitable growth and is also reducing poverty. To understand whether growth is sustainable, it is important to come to grips with the drivers of growth. Economic theory and cross-country evidence suggest that a more diverse economic base—achieved through structural transformation—increases the likelihood of sustained economic performance and growth. Such structural transformation involves the reallocation of labor from low- to high-productivity sectors, and the rate of such structural change can encourage growth significantly. Rodrik (2014) posits that rapid industrialization or structural change toward high-productivity sectors can help shift countries into middle or upper income status; this follows the notion that modern manufacturing industries exhibit unconditional convergence to the global productivity frontier.

Table 1-3 presents the contribution of the various sectors to GDP between 1990 and 2012. We see that the agricultural sector remains a dominant contributor to GDP, particularly in West, East, and Central Africa, although there has been an observable downward trend in agriculture in most regions. In the African case, where industrialization has taken place, it has generally been dominated by mining rather than manufacturing activities. In fact, in most regions and periods since the 1990s, manufacturing has declined substantially. This weakness in manufacturing represents a key indicator alluding to the vulnerability of the growth and development trajectory of many of Africa’s economies. In contrast, the tertiary services sector has grown to be the largest contributor to GDP for most SSA nations.

Africa’s growth dynamic thus far has been characterized, on average, by a move into resource-based production, with small gains spilling over into manufacturing output. Indeed, some of the highest growth has been recorded in low-skilled, low productivity jobs in the urban services sectors of these economies (see Newman and others 2016a). Africa’s transition away from primary sector activities toward tertiary sector activities has, in other words, not resulted in a discernable shift toward a more sustainable growth path. Attempting to quantify the effect of this structural change, McMillan and others (2014) estimate that this restructuring made a sizeable negative contribution to overall economic growth between 1990 and 2005, by as much as 1.3 percent per annum on average.1 In this sense, their estimates show that labor moved in the wrong direction, becoming less productive. In Nigeria, Ajakaiye and others (2015) also find that the manufacturing sector has become more capital-intensive over time, hampering the capacity of this sector to absorb significant volumes of labor. Rodrik (2014) characterizes this phenomenon as premature deindustrialization, where a significant proportion of the population is absorbed into low-productive, informal sector work. This begs the question whether Africa will be able to skip a stage of economic development that all other developing nations have gone through (namely moving from a core, vibrant manufacturing base toward growth) and effectively reap the benefits of a mining- and services-led growth path in the pursuit of long-run growth and employment creation. On current evidence, it would appear that a “manufacturing...