![]()

CHAPTER 1

Symptoms and Diagnosis

Methods for Detection and Diagnosis of Cancer

In the case of solid tumors, initial diagnosis can be linked to the detection of an unusual mass of cells in the body. These masses of cells might be detectable by physical examination, but frequently are detected using imaging techniques that allow visualization of tissues inside of the body, such as X-rays, computed tomography imaging (CTI, CT, or CAT) scans, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, and positron emission tomography (PET) scans. X-rays are a type of energy with very short wavelengths that cannot be seen by humans and can pass through most tissues of the body. Bones and other dense tissues block some of the X-rays from passing through and form a shadow (appear white on a black background) in images. Images produced from X-rays can show information from a single direction, but CAT images consist of a type of X-ray image that is done in cross sections, or slices, through the body so that you get more detailed images than X-rays. MRI captures a detailed series of images that show cross sections through tissues, but does not use X-rays. MRI uses a very strong magnet to align the polarity (a type of directionality) of the hydrogens (protons) present in our body (largely found in water). A radio wave is passed through the person, making the protons change polarity. Once the radio wave is removed, the protons flip back to their original orientations, releasing energy. This released energy is sensed by the machine to generate an image based on how quickly the energy is released from the protons. The result is a series of very high-resolution images showing the relative size and position of tissues and organs. MRI imaging is usually not used for diagnostic purposes unless a person is at high risk for cancer, since the detailed images from an MRI can produce many false positives (natural variations of cell densities that are not cancer). PET scans leverage a metabolic feature of most cancer cells because cancer cells consume more sugar than most noncancerous cells. For a PET scan, weakly radioactive sugar is introduced into the patient. As the cancerous cells consume high levels of the radioactive sugar, they accumulate the radioactivity, which can be detected in the PET scan. PET scans can reveal any tissue that contains cells consuming relatively high amounts of sugar, including cancer cells and cells that divide quickly as a normal part of their function in the body (such as hair and intestinal lining).

If a mass of cells is detected through imaging techniques, and the mass is amenable to surgical sampling, a biopsy is done. Tumor samples are prepared for histological examination by a pathologist using a microscope. Microscopic analyses of a biopsy are frequently needed to determine if a mass of cells is benign, meaning it is not metastatic cancer, or malignant, meaning it has undergone metastasis. Microscopy magnifies histological samples to reveal the shape of each individual cell and the relative position of small groups of cells. These features allow pathologists to distinguish between metastatic cancer masses and masses of benign cells. The benign masses will have maintained more of their original cellular shape and structure, which suggests they have maintained contact inhibition. A histological analysis can also allow detection of the mitotic index, the percentage of cells in the sample that were actively dividing at the time that the sample was collected. A high mitotic index is suggestive of cancer, and the higher the mitotic index, the more aggressive the cancer. In some cases, the mitotic index will be taken into consideration when staging a cancer or when considering the prognosis of the cancer patient. Variations of histological analysis can be used to obtain information about protein composition of the cancer cells. For example, immunohistochemistry (IHC) uses antibodies that bind to specific proteins to highlight the presence and relative abundance of those proteins in the cells. IHC can help identify what type of cell is present in the tumor. Additionally, samples can be probed for gene expression through approaches such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH). These two methods can detect genetic abnormalities in the cancerous tissues. In addition to imaging scans and histological analysis capable of physically detecting masses of cells in the body, some blood tests exist that allow the detection of cancer biomarkers. A biomarker is a biological material that can be measured to indicate the presence or absence of a disease. Much like high glucose levels in urine is a biomarker for diabetes, certain factors might be present in the body of a cancer patient that are absent in a healthy patient. These materials do not necessarily cause cancer, but correlate to the presence of cancer in a patient. The use of these approaches would vary depending on the type of cancer in question and is critical in diagnosing the presence of cancer cells and the staging of the cancer. Methods of staging cancers will be unique to each type of cancer, but usually is comprised of a numbering or lettering system to indicate how advanced and/or dangerous the cancer is. Staging of cancers is part of the diagnosis process that informs both treatment and prognosis of the disease.

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Skin Cancer

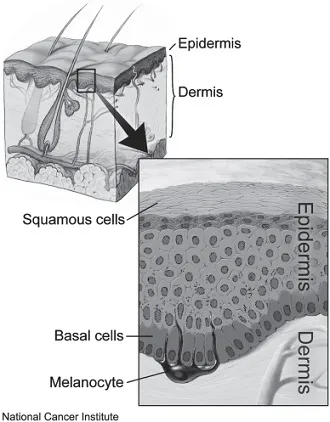

Skin cancer is the most common type of cancer reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States and presents in one of three forms: basal cell, squamous cell, and melanoma skin cancer. Additional types of skin cancer include Bowen disease (a type of squamous cell cancer), actinic keratosis (which can develop into squamous cell cancer), lymphoma of the skin (a rare cancer of the immune system that starts in the skin), Merkel cell sarcoma (cancer of cells in the epidermis that associate with nerves), and Kaposi sarcoma (cancer of cells that line blood vessels or lymph nodes). Basal and squamous cell skin cancers are the most common, grow relatively slowly, and rarely spread to other parts of the body. Basal cell skin cancer begins in cells that reside in the basal layer of the skin, while squamous cell skin cancer begins in cells that reside in the squamous layer of cells. Melanomas begin as normal cells called melanocytes, cells that produce the pigment melanin. Melanoma is less common, but leads to more deaths than the other types of skin cancer combined. In all three forms of skin cancer, the cells that become cancerous are part of the epidermis, or the outermost layer of cells on the skin (Figure 1.1). Squamous cells are located on the top surface of the skin, whereas basal cells and melanocytes are located at the base of the epidermis, near the dermis where glands, blood vessels, and nerves can be found. Melanomas begin in the skin, but they can also originate in other pigmented tissues such as the eye or the intestines. In 2014, 76,665 individuals were reported with skin melanomas and 9,324 (12 percent) of them died. The incidence of melanoma is highest among white men and women. Melanocytes are naturally mobile before they become cancerous, so they metastasize very frequently, which contributes to the high mortality rate for melanomas.

Figure 1.1 Layers of the Skin. The dermis and epidermis layers of the skin are drawn with an inset showing a close-up view of squamous cells, basal cells, and melanocytes. By Don Bliss (Illustrator) (Public domain or public domain), via Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c1/Layers_of_the_skin.webp

The primary symptom of a skin cancer is a change in the color or texture of skin. Skin cancers are distinct from common moles, which are noncancerous growths on the skin resulting from clusters of melanocytes, which give color to the skin. Some moles called dysplastic nevi (DN) have the potential to develop into melanoma. They appear larger than common moles with more variations in color, and have borders that are difficult to see. In attempts to detect skin cancers, a mole or previous growth could change, a sore can change during healing, or new growth could occur. When considering the likelihood that a change in skin might be skin cancer, the CDC suggests that individuals consider A-B-C-D-E:

A stands for asymmetrical, meaning that the new growth has an irregular shape.

B would stand for border, where an irregular, jagged, or difficult-to-see border would be of concern.

C indicates color, where uneven color would be of concern.

Diameter, D, becomes a concern when it is larger than an approximate size of a pea.

E stands for evolving, meaning that the skin is continuing to change in the previous few weeks or months.

Any of these changes would warrant a visit to a physician to determine if the changes are potentially skin cancer. A physician might use a dermatoscope, a special magnifying lens and light, to more clearly see changes in the skin. If the area is considered potentially cancerous, then a biopsy would be taken from the skin in question. As much of the concerning area as possible will be removed, and the healing may leave a scar. A physician might choose to remove an area of skin by shaving off the top layer of skin with a blade, or using a cookie cutter–like tool for a punch biopsy removing a circle of skin, or using a surgical knife if the physician feels that the sample needs to include cells from deeper layers of the skin. The biopsy is used to prepare a histological sample that can be observed by a pathologist using a microscope. If findings are not clearly cancerous from the histological observations, additional tests may be performed on the sample such as IHC, FISH, and CGH, as described above. When IHC approaches are inconclusive, FISH and CGH can help distinguish between melanoma and DN by identifying changes in the overall genomic structure of the patient’s sample cells.

If melanoma is detected, then the cancer thickness and mitotic index of the tumor will be determined. These features allow the pathologist to assign a grade to the melanoma. Although there are multiple staging systems for skin cancer, the American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) suggests the TNM system, where T means that the primary tumor has grown within the skin. This category is based on the thickness of the melanoma, using the Breslow measurement. Essentially, a melanoma smaller than 1 mm is less likely to spread to other parts of the body. The mitotic index and level of ulceration are used to stage different values for a T tumor as follows:

TX (tumor cannot be assessed)

T0 (no sign of primary tumor)

Tis (carcinoma in situ, or only in the epidermis with no spread)

T1a (less than 1 mm thick and mitotic index less than 1/mm2)

T1b (less than 1 mm thick and mitotic index 1/mm2 or more)

T2a (between 1.01 and 2 mm thick without ulceration)

T2b (between 1.01 and 2 mm thick with ulceration)

T3a (between 2.01 and 3 mm thick without ulceration)

T3b (between 2.01 and 3 mm thick with ulceration)

T4a (more than 4 mm thick without ulceration)

T4b (more than 4 mm thick with ulceration)

The next stage is called N, which stands for lymph nodes, meaning that the melanoma has spread from the skin to one or more lymph nodes as follows:

NX (cannot be assessed)

N0 (no spread to nearby lymph nodes)

N1 (spread to nearby lymph nodes)

N2 (spread to two or three nearby lymph nodes or to nearby skin that is near a lymph node)

N3 (spread to four or more lymph nodes, or lymph nodes that are clumped together, or to the nearby skin)

The M stage indicates that the skin cancer cells can be found in additional organs in the body and may include detection of the cancer biomarker LDH, indicating that the cancer has metastasized as follows:

M0 (no distant metastasis)

M1a (metastasis to skin, below the skin, lymph, or distant parts of the body with normal blood LDH levels)

M1b (metastasis to the lungs, with normal LDH level)

M1c (metastasis to any other location with elevated blood LDH levels)

Once the T, N, and M status has been determined, then an overall stage is used to describe the cancer as stages 0, I, II, III, or IV, where higher numbers associate with more serious cancers. This level of staging can be complex with many subheadings for each overall stage, and care should be taken to fully understand the staging employed by the physician.

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. The CDC reports that in 2014, of the 215,951 individuals diagnosed with lung cancer, 155,526 (72 percent) died. Lung cancers originate in cells of the lungs, but can spread to other parts of the body. Cancers of other tissues can spread to the lungs, impairing lung function—but these cancers would not be classified as lung cancer. Healthy lungs allow gas exchange into and out of the blood (CO2 out, O2 in). The bronchi connect the lungs to the windpipe or trachea, and lead to small tubes called bronchioles, which terminate in air sacs called alveoli. Sympt...