![]()

1

WIKIPEDIA IN SHORT

Numbers, Rules, and Editors

Wikipedia: Basic Facts

To analyze Wikipedia as a phenomenon and a community, it may be useful to understand its origins, history, and growth. Wikipedia, contrary to popular belief, was not the first wiki. A “wiki” (derived from the Hawaiian word for “quick” and named after the Wiki Wiki shuttle at Honolulu International Airport) is a website technology that tracks users’ changes, which can be made in a simplified markup language (allowing easy additions of, for example, bold, italics, or tables without the need to learn HTML syntax). The first wiki was created and released in 1995 by Ward Cunningham as WikiWikiWeb. WikiWikiWeb was an attractive choice to enterprises and was (and sometimes still is) used for communication, collaborative idea development, documentation, intranets, and knowledge management. It grew steadily in popularity.

In 2000 Jimmy “Jimbo” Wales, then the CEO of Bomis, started up his encyclopedic project, Nupedia, which was meant to be an online encyclopedia, with free content written by experts. In an attempt to meet the standards set by professional encyclopedias, the creators of Nupedia based it on a peer-review process. The website relied on an assumption that scholars would generate content for free. But Nupedia developed slowly, and its editor in chief, Larry Sanger, hired by Wales to oversee its development, adopted a suggestion by Ben Kovitz1 to use wiki software and philosophy for the creation of encyclopedic content. This idea resonated with Wales’s vision of making a publicly editable and accessible encyclopedia, and in January 2001 Wikipedia.com (later Wikipedia.org) was launched, originally as a content feeder for Nupedia.

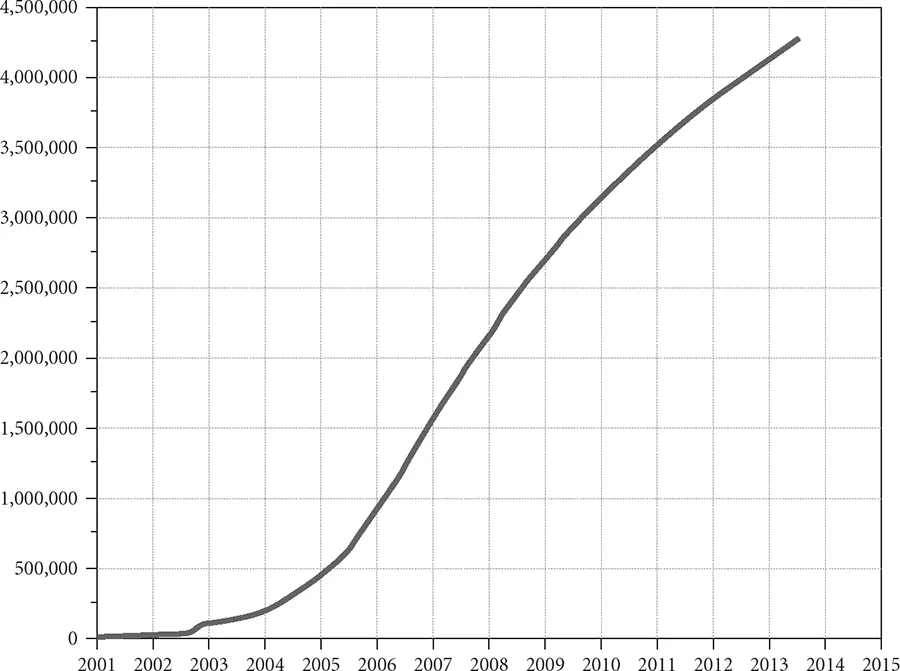

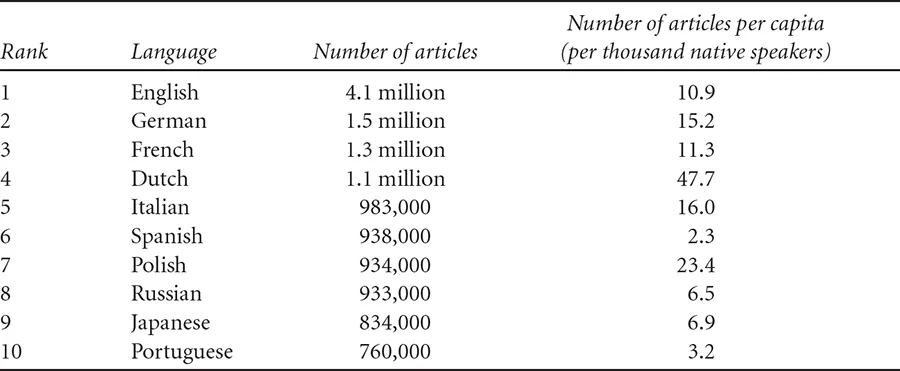

It was an instant success. The first year produced about twenty thousand articles, and the second year brought a nearly fivefold increase. Meanwhile, either Nupedia was not reaching the academic community with its message or the academic community was not interested in its mission. In September 2003 it was closed down, with only 24 articles finished and 74 in development. By then, the English Wikipedia already had more than 150,000 articles. (See Figure 1.1.) In the meantime, many editions of Wikipedia in other languages had started to spin off. The first was German (originally a subdomain of Wikipedia.com launched on March 16, 2001). The largest Wikipedias as of January 2013 are listed in Table 1.1.

The total number of articles in all Wikipedias (in more than 270 languages) exceeds twenty million. The English Wikipedia is by far the leader. However, positions from number 2 to number 10 are relatively close. There is a larger gap between number 10 and number 11, the Swedish Wikipedia, which has 564,000 articles. When the number of articles per capita of native speakers is considered, among the ten largest Wikipedias, the Dutch one takes the lead by far, and the Polish one also significantly stands out. The English Wikipedia is near the middle in this ranking (at number 5, almost equal to the French one), which is surprising given that English is the most popular second language in the world—practically a lingua franca, unlike Dutch and Polish. Approximately twenty-nine thousand English Wikipedia users declare themselves native speakers,2 and twenty-seven thousand who contribute to it are self-declared nonnatives. On the basis of these rough estimates, there are about as many nonnative editors as native ones, probably because the English Wikipedia had a head start on the other Wikipedias (especially in media coverage). In addition, the relative number of articles on the English Wikipedia is surprisingly low compared to those of other major languages. Furthermore, the page and editor growth rate on the English Wikipedia has slowed, while organizational costs of coordination have increased (Suh, Convertino, Chi, & Pirolli, 2009).

FIGURE 1.1. Number of articles on the English Wikipedia. Source: Illustration by HenkvD, [[File:EnwikipediaArt.PNG]].

TABLE 1 1 The ten largest Wikipedias in the world as of January 21, 2013

SOURCE: “List of Largest Wikis,” 2013.

However, number of articles alone is not a good indicator of an encyclopedia’s quality: many articles on the English Wikipedia are much better written and richer in sources and data than articles on the same subjects on other Wikipedias. Perhaps editors on the English Wikipedia more often decide to deepen and expand the existing articles rather than seed stubs (or start short new articles). Moreover, since the number of articles is the simplest and the most visible measure of encyclopedic size, some Wikipedias employ bots (software scripts) to automatically create articles, such as on villages in China (each receiving a separate entry) by using geographic lists and maps. This expansion strategy has been used by most Wikipedias since October 2002, when a bot added thirty thousand stubs on American cities and towns to the English Wikipedia in little over a week. Clearly, nonhuman contributors have a significant influence on the development of Wikipedia (Niederer & van Dijck, 2010; Geiger, 2011; Halfaker & Riedl, 2012). Thus, all the metrics should be taken with a grain of salt.3 Note, however, that Wikipedia’s growth is slowing (Suh et al., 2009), and some studies indicate that its growth follows an S curve (Lam & Riedl, 2011), which is not surprising.

Also interesting is that the criteria for topic notability vary significantly among Wikipedias. In a study of twenty-five Wikipedias, only 1 percent of their article topics were covered in all of them, and as many as 74 percent of the article topics were present in one language only (Hecht & Gergle, 2010). Yet the various Wikipedias have a similar rational and meritocratic development path, because the differences between average and featured (exemplary) articles within each Wikipedia are significantly greater than the differences between the Wikipedias (Hammwöhner, 2007). Different-language Wikipedias, after they reach a certain level of maturity, develop along similar patterns (Zlatić, Božičević, Štefančić, & Domazet, 2006).

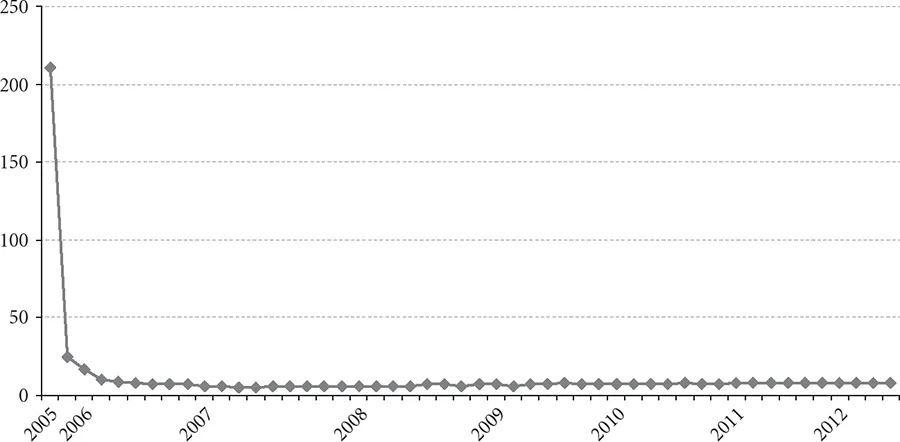

In spite of its tremendous overall growth and undisputed maturity, the development of the English Wikipedia in some ways does not seem to be slowing down. For instance, one intriguing measure of Wikipedia stability is the time it takes to achieve ten million edits (a measure independent of the number of contributors). It took 211 weeks for the number of edits to increase from ten million to twenty million and then 17 weeks to increase to thirty million. The pace soon stabilized at about 7 weeks and has stayed there ever since. In 2007 it sped up to a little below 6 weeks, and since 2011 it has been 8 weeks; nevertheless, it is amazingly consistent. See Figure 1.2. It is quite possible that editing Wikipedia has become part of a work-life routine for many editors. Also, the proportion of administrative and other coordinative edits to the overall number of edits may be increasing (Kittur & Kraut, 2008). In August 2013 the total number of edits on the English Wikipedia reached 632 million.4 Yet when the variations in the number of new editors, the number of those quitting, and general activity are taken into account, the stability in this data is surprising.

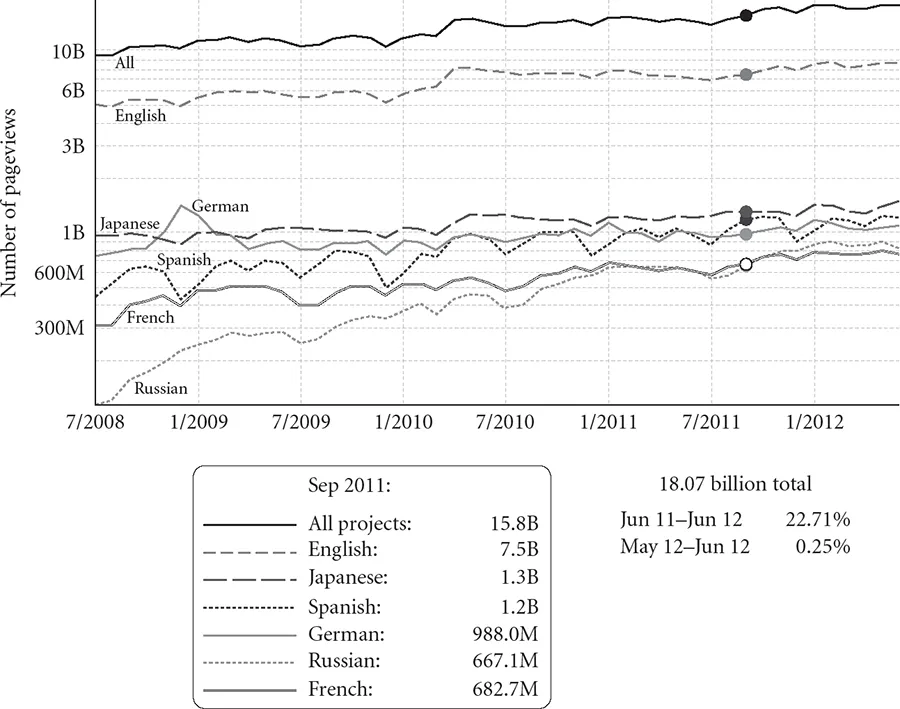

Other Wikimedia projects, and Wikipedias in particular, flourish as well. “As of October 2013, Wikipedia includes over 29.8 million freely usable articles in 287 languages that have been written by over 42 million registered users and numerous anonymous contributors worldwide. According to Alexa Internet, Wikipedia is the world’s seventh-most-popular website” (see [[History_of_Wikipedia]]). The total number of edits on all Wikimedia projects as of August 2013 exceeded 1.9 billion,5 and the number of pageviews has been growing steadily (see Figure 1.3, which covers 2008 to 2012). Similarly, the number of unique visitors rose from 242 million in January 2008 to 469 million in June 2012.6

FIGURE 1.2. Number of weeks between every ten million edits on the English Wikipedia. Source: [[User:Katalaveno/TBE]] (retrieved September 2, 2012).

The Wikimedia community7 has evolved, and some changes are not as positive as the pageview statistics would imply. For instance, according to the report “Editor Trends Study,” on the five largest Wikipedias, by the Wikimedia Foundation, until 2005 nearly 40 percent of editors were still active a year after they started editing. However, after 2007, no more than 15 percent of editors remained active after a year (Wikimedia Foundation, 2011b). Clearly, integration with the Wikimedia community has become more difficult. This may be related to increased decentralized and informal gatekeeping—that is, small-scale actions of experienced community members aimed at discouraging newcomers (Shaw, 2012), possibly to assert status and flaunt seniority. The community has undertaken many efforts to reverse this decline (see, e.g., [[WP:Teahouse]]).

According to Wikipedia Editors Study, published in April 2011, 91 percent of all Wikipedia editors are male (Wikimedia Foundation, 2011a, p. 2). This figure may not be accurate, since it is based on a voluntary online survey advertised to 31,699 registered users and resulting in 5,073 complete and valid responses (p. 42). It is possible that male editors are more likely to respond than female editors. Similarly, a study of self-declarations of gender showing only 16 percent are female editors (Lam et al., 2011) may be distorted, since more females may choose not to reveal their gender in a community perceived as male dominated. Even taking into account that opt-in surveys of Wikipedia participation must be biased (Hill & Shaw, 2013), studies consistently show that the number of female editors is dismayingly small, especially when the gender gap is much smaller among nonediting readers (Glott, Schmidt, & Ghosh, 2010; Bywater, 2011). This extreme disparity is difficult to explain just by Wikipedia’s geeky past or a reproduction of social and economic inequalities (Morell, 2010).8 Some studies suggest that it may be a result of a high level of conflict on Wikipedia or a generally critical and uncooperative environment (Collier & Bear, 2012). Clearly, gendered perception of editor roles and careers could be at play, too (Bourne & Özbilgin, 2008). The phenomenon is far from being sufficiently explored and requires more Wikipedia-focused studies from a variety of angles, as well as studies of collaboration technologies and gender (Zhang & Kramarae, 2008). In general, the free-cultural-works and free/libre-and-open-source-software (F/LOSS) movements have a significant gender gap (Reagle, 2013).

FIGURE 1.3. Pageviews for all Wikimedia projects, July 2008–June 2012. Note: The box shows the data for September 2011, the point selected on the graph. Source: http://reportcard.wmflabs.org (retrieved August 28, 2012).

As a possible side effect, Wikipedia may be missing more biographies of women than of men compared to Britannica, even though in general Wikipedia provides better coverage and more comprehensive articles (Reagle & Rhue, 2011). Also, articles about gender inequality and topics of interest for women may be more likely to be deleted (Carstensen, 2009). However, there is a huge variation in recognizing people across different-language Wikipedias (Callahan & Herring, 2011). Even clear sexism occasionally occurs: the New York Times writer Amanda Filipacchi observed that Wikipedians categorized American women novelists separately from men, who remained in the general American novelists category (Filipacchi, 2013). After publication of Filipacchi’s article women authors were reincorporated into the general category.

Another finding from the Wikipedia Editors Study (Wikimedia Foundation, 2011a) is that as many as 61 percent of Wikipedia editors have finished college (8 percent attaining a doctorate, 18 percent a master’s, and 35 percent a bachelor’s degree), so the stereotypical image of a Wikipedian as a nerdy kid or, most commonly, a high school student (Greenwood, 2012) is clearly false. Only 36 percent of Wikipedia editors are able to write computer programs by themselves, so the geeky stereotype is also partly false. Moreover, Wikipedia editors are not so young; the average age is thirty-two, and 27 percent are twenty-one or younger. In another major study, however, 50 percent of respondents report being younger than twenty-two (Glott et al., 2010). In general, most quantitative studies of Wikipedia make some assumptions and are vulnerable to one methodological bias or another, since bias-free recruitment of subjects is a challenge.

Reasons for participation in surveys among Wikipedians vary greatly, and survey interpretation depends on the paradigm and discipline of the researcher. Some studies indicate that a dominant motivator for participating in surveys is the possibility of gaining recognition in the community (Forte & Bruckman, 2005), which is particularly attractive when paired with a relatively low transactional cost of entry and participation (Ciffolilli, 2003). Other motivators are gaining self-fulfillment, having fun, and acquiring and sharing knowledge (even if just to boost one’s ego; Rafaeli & Ariel, 2008), maintaining a positive self-image, contributing to the common good (Ciffolilli, 2003; Baytiyeh & Pfaffman, 2010; Yang & Lai, 2010), and enjoying a sense of accomplishment (Kuznetsov, 2006). Such reasons are not uncommon for other online knowledge-sharing activities (Lee & Jang, 2010). As research on other virtual communities shows, many users participate to elevate their communal social status (Lampel & Bhalla, 2007) or simply feel that they belong (Lampe, Wash, Velasquez, & Ozkaya, 2010). Other motivations may be ideological (e.g., a strong belief that information should be free) and driven by principle (Nov, 2007; E. G. Coleman, 2013). Incidentally, even as beginners, those who become die-hard Wikipedians differ in how they participate in the community and edit (Panciera, Halfaker, & Terveen, 2009). This could indicate a significant selection bias in the Wikipedia community. Long-standing Wikipedians are sometimes perceived as a different kind of person by newcomers, and this perception adversely affects retention of new editors (Antin, 2011). They also take the role of gatekeepers in the eyes of the newcomers, especially in the case of breaking news articles (Keegan & Gergle, 2010).

At the same time, high user retention in the Wikipedia community does not have exclusively positive effects, contrary to popular belief. In fact, moderate levels of membership turnover on Wikipedia improve the production of collaborative articles (Ransbotham & Kane, 2011).

Basic Rules and Norms

The English Wikipedia, and to a lesser extent the Polish Wikipedia, has hundreds of rules, norms, policies, and guidelines. Whereas many other virtual communities rely on governance by a few leaders (Lessig, 1999; Butler, Sproull, Kiesler, & Kraut, 2007), the Wikipedia community establishes these strictures. A proliferation of rules, statutes, deliberations, and meetings is typical of truly community-driven cooperatives (Whyte & Whyte, 1991; Cheney, 2002). Rule formalization and emergence of coercive institutional structures are discussed later. Here I summarize the chief policies pertaining to editing on most Wikimedia projects.

Wikipedia is distinguished from other contemporary Internet fora by one hard-and-fast rule: no personal attacks (NPA),9 which possibly evolved from Usenet traditions. Editors are not allowed to attack each other, not even in retaliation for a personal attack; the attacked editor must try to reason with the attacker. Retaliation most likely leads to both parties being blocked. If an intervention is necessary, an administrator can be asked for help (or take the initiative to do so, upon spotting aggressive behavior). Editors are expected to comment only on content. A similarly strong and related norm is civility (CIV). It requires editors to treat each other with respect and consideration and to refrain from personal comments. Wikipedians are advised to forgive and forget (FORG) when insulted or wronged.

Enforcement of the civility and no-personal-attacks rules depends on the project, the people involved, and the situation. Sometimes a single snide comment may be a reason for blocking a user, at other times a major offense will go without a reaction. In one case, a Wikimedia Foundation employee who was also an administrator on the English Wikipedia called his disputant “a troll.” Although the disputant had a long history of criticizing Wikipedia, in this instance he was actually making a point in a discussion and in my judgment not trolling. I suggested the employee retract the name-calling comment, but he refused.10 Nobody else reacted. Clearly, the norm was bent because of the status of the people involved, one high, one low, but the outcome was not typical. I have blocked other admins (administrators) for not mincing their words when they should have and have witnessed others doing so often enough to believe that status and position in the community are no protection from policy enforcement. In general, all users, regardless of their experience and standing in the community, are expected to follow the rules of etiquette (EQ). The rules of civilized discourse reflect those used in academia: discussion is based solely on the strength of the argument rather than eristic tricks or participant status. In any case, blocking users is meant to be preventive rather than punitive and to ensure ...