![]()

Chapter 1

Explaining Enduring Labor Codes in Developing Countries: Skill Distributions and the Organizational Capacity of Labor

Over the last century in Latin America, workers have been crucial political actors. Their incorporation into political movements, parties, and the state has allowed governments to rise, or condemned them to fail (Collier and Collier 2002). Organized labor has mobilized massive numbers of voters at critical moments during elections, and it has taken to the streets in protest at reforms. This is as true over the last century as it is today, even if it takes a new form in recent decades (Etchemendy and Collier 2007).

The institutional foundations of labor’s strength in Latin American are the region’s labor codes. Latin America’s labor laws are among the most protective and rigid in the world, restricting the ability of employers to fire workers and providing extensive employee benefits and organizing rights for unions (Heritage Foundation 2009). These laws give workers rights in both the economic and political spheres, and serve as a gateway to participation in state-organized social security programs. And against all expectations, they have remained this way even during the era of globalization and restructuring for economic competitiveness (Murillo 2005; Murillo et al. 2011). But legal provisions governing labor are also highly uneven in the region, with considerable variation across countries and economic sectors. What explains variation in labor law provisions, both those regarding the individual hiring and firing of workers and the collective action of organized workers? And why have Latin America’s labor codes been the hardest economic policy area to reform?

Too often, past analyses have treated these as separate questions. They have developed explanations of initial labor law development and differentiation (Collier and Collier 2002 is a masterpiece in this regard) or of the process of reform and resistance (Murillo 2005; Murillo and Schrank 2005; and Cook 2007 are outstanding examples). This work provided significant insights into labor’s incorporation into the state or political parties, and into the role of parties and competition and historical legacies in shaping reform trajectories. But rarely have these two literatures been able to dialogue with each other. Indeed, the Latin America of the reform period was posited to be fundamentally different from that of the incorporation period.

With the perspective of history, this book argues that the answers to the questions of difference and stability in labor codes are interrelated. Looking at Latin America now, after the dust has settled from the flurry of reformist measures and economic liberalization of the 1980s and 1990s, what stands out is continuity over the long term. Thousands of changes in specific measures within labor codes have not fundamentally altered legal systems that first came into force sixty, seventy, and eighty years ago. This is a perspective that has only become possible in recent years, with the advantage of the long span of history. And it is a perspective that can only be gleaned by looking at labor codes in a new way—as coherent bodies of regulations, and not simply as piecemeal measures. It is in these comprehensive labor codes that we can see the striking continuity over the last century. In other words, by looking at the forest that is the legal environment governing labor, rather than the trees of specific laws, we can appreciate how much continuity has reigned in the region, even despite change.

This chapter develops a microfoundational theory to explain variation in labor law outcomes across Latin America, and by extension, across all developing countries. Its basic premise is that country-level differences in labor codes, and the stability of those labor codes through time, can be explained by a common set of factors. First, higher skill levels in the workforce are posited to be tied, over the long term, to more protective and more generous laws governing individual labor relations. Second, greater organizational capacity among workers is hypothesized to permit more effective political action such that, over the short to medium run, laws governing collective labor relations will be more developed and provide greater rights and freedoms to labor unions. Together, these two hypotheses allow us to explain long-term variation in the labor codes of different countries. Short-term deviations from the predicted equilibria are possible, but they are likely to be much more fragile and short lived, emerging only when nondemocratic governments or labor-allied parties are able to temporarily impose such measures on the system.

Several steps are required to make this argument. First, the chapter develops a typology of “labor law regimes” that takes into account multiple elements of each country’s legal code. These regimes allow us to see how specific laws interact, especially those governing the individual contracting of workers, on the one hand, and the collective activity of worker organizations in unions, on the other. The result is an objective, measurable understanding of labor codes that permits comparison over time and across countries.

Next, the chapter lays out the theoretical framework for understanding the initial origins and historical development of the labor law regimes. Because these legal regimes tend to be lasting and stable, it focuses first on long-term economic constraints of labor policy. It argues that over the medium to long term, labor relations are constrained by existing economic conditions, in particular the resource base of labor and capital and national development programs. Labor laws must take into account the economy’s underlying economic conditions—most important, the skill distribution among workers and the skill needs of employers—or face constant pressure for change. For this reason, the theory developed below treats skill profiles as a critical constraint on labor law development over long periods of time.

The theory further argues that political factors play a role primarily in the short to medium run and in specific, focused reforms. Politics provides the mechanisms for interest articulation that result in labor legislation. Among these mechanisms, I focus most attention on labor’s role in the political process, which I call the “organizational capacity of labor.” This concept captures the extent to which labor is united as a political and economic actor, has effective leadership and substantial resources, and functional ties to political parties and leaders. It is complemented by other political factors, including the institutional framework of the regime in power, government partisanship, legacies of previous governments and labor regulations, and pressures from international financial institutions and private investors.

The theory concludes by mapping the relationship between these economic and political factors, on the one hand, and resulting long-term labor law configurations, on the other. This provides a framework for the empirical work that follows in subsequent chapters, which consists of both quantitative cross-national testing in Chapter 3 and historical case studies in Chapters 4 through 6. The final section of the chapter discusses how the theory developed here relates to previous work and outstanding questions about labor law in Latin America.

A Preview of the Argument

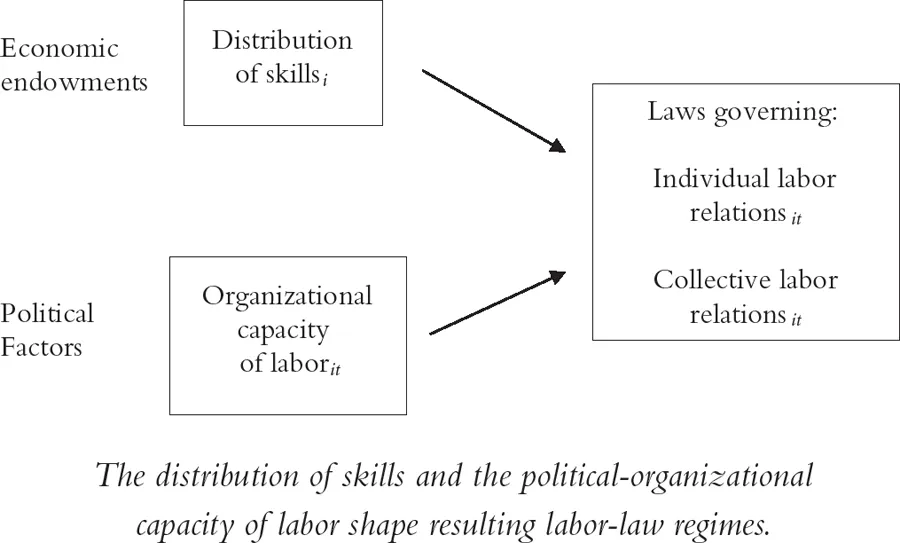

For ease of understanding, Figure 1.1 depicts the key elements of the theory developed in this chapter in schematic fashion, prior to their full development in later sections. Begin on the right-hand side, which describes the dependent variable: the labor law configuration in country i at time t. Note that the outcome is a single configuration, or “regime,” that contains interrelated individual and collective measures. The emphasis is on explaining not just particular labor law measures (although these will be given significant consideration), but the labor code as a whole.

The left-hand side of the diagram displays the causal factors that are hypothesized to determine labor law configurations. First, the theory developed in this chapter gives special attention to the way that economic resource endowments shape labor relations and labor law. Among these factors, it hones in on the distribution of the skills in the economy—across workers, geography, and industries—as a medium- to long-run constraint on labor law configurations. The subscript i refers to the country-level skill distribution; the lack of a time subscript indicates that the skill distribution is taken as fixed in the medium to long term (since worker training and education sufficient to alter the skill distribution in the economy take significant time). Skills determine the demands that workers make regarding workplace treatment and rights, as well as the relative responsiveness of employers and governments who need worker support. I argue below that it is this slow-changing skill endowment that makes labor law configurations so lasting and resilient. Empirical evidence in Chapter 3 will show that countries throughout Latin America have only marginally changed their relative skill profiles over recent decades, and that labor codes have remained similarly stable over that same period.

Second, political factors shape Latin American labor codes. I concentrate most attention on what I term “the organizational capacity of labor.” This concept captures the political institutions and processes that shape interest articulation and determine regulation, allowing workers to effectively demand different kinds of labor rights and benefits. The subscripts i and t indicate that, at the country level, labor’s organizational capacity may display short- to medium-term fluctuations. Union strength, leadership, and political ties can all change through time, even from leader to leader or government to government. As a result, they can have dramatic effects on the labor code in the short run. On multiple occasions, labor law reforms have been used throughout the region to court votes or stave off worker unrest, or to attract investment or reassure creditors.

Figure 1.1. An Overview of the Argument

As Figure 1.1 shows, both skills and labor organization have an impact on the entire labor code. Nevertheless, I will argue that each is more closely associated with one portion of the labor code. The distribution of skills plays a dominant role in determining the medium-term range of possible individual labor regulations, while the organizational capacity of labor is most closely associated with ongoing regulation governing collective labor relations.

In addition to labor’s organizational capacity, a number of additional political factors highlighted in earlier work on Latin American labor also play a role in the final shape of labor regulation. These include the governing regime type (authoritarian or democratic, for example) (Haggard and Kaufman 2008; Mares and Carnes 2009), government partisanship (Murillo 2005; Murillo and Schrank 2005; Murillo et al. 2011; Huber and Stephens 2012), legacies of past governments and existing policies and organizations (Cook 2007; Etchemendy and Collier 2007; Etchemendy 2011; Caraway 2012), and the international system (Ronconi 2012). They are not depicted in Figure 1.1, as they can be understood as exerting their influence through, or in interaction with, the organizational capacity of labor.

With this schematic overview of the book’s argument in mind, we can enter into the details of the theory.

1.1. Conceptualizing Labor Law Configurations

This study takes national-level labor regulation as its dependent variable. It focuses on the set of written legal provisions that govern labor relations within a national economy. In Latin America, these laws are generally the product of the legislature. The executive, however, has also played a very active role in formulating labor regulation, and in many countries has used decree powers to make significant changes to the laws governing workplace treatment, hiring, and firing. And in some countries, most notably Uruguay, the judicial branch also plays an important role in setting standards in labor relations through its interpretation of the constitution and other laws. Thus the labor laws examined in this study are those statutes written, publicly promulgated, and published in the domestic Código Laboral, regardless of the branch of government in which they originated. I use the terms “laws” and “regulation” interchangeably, for ease of presentation, to indicate this written body of state-sanctioned regulatory policy.

It is crucial to distinguish the labor laws examined in this book from other important labor market and political outcomes. Labor regulation, as understood here, is restricted to the written laws “on the books.” In Latin America, compliance with labor law is known to be far from universal, and to vary across countries and policy areas, but the dimensions and explanations for evasion are still poorly understood. Important work has recently begun examining labor law enforcement (Mosley and Uno 2007; Almeida and Carneiro 2007; Anner 2008; Ronconi 2010, 2012). Based on studies of a small set of cases and limited temporal scope, this literature suggests that compliance is enhanced when governments undertake stronger enforcement efforts, and that more democratic and more left-leaning governments are more likely to seek to enforce their labor laws (Ronconi 2010, 2012), and that compliance increases and violations of labor law decrease as foreign investment increases (Mosley and Uno 2007; Greenhill et al. 2009; Ronconi 2012). Nevertheless, much work remains to be done to understand the political and economic determinants of enforcement and compliance. This book incorporates insight from these nascent studies wherever possible, but it must leave a fuller study of the politics of enforcement and compliance to future work.

Labor laws have an outsize impact beyond the workplace in Latin America, both economically and politically. First, they set the terms for participation in the region’s employment-based social security programs. Legal employment constitutes the point of entry to a host of state-regulated benefits, including pensions and health care. Workers who are employed “off the books” do not enter into these social programs. Likewise, labor laws confer political rights—to organize and meet, to collect dues, to strike—that allow workers to more easily make their voice heard, especially through alliances with political parties. Indeed, labor laws can set up two tiers of citizenship—one for formally registered workers, who are “insiders” to the state’s social security measures and to certain political parties, and one for informal-sector workers, who are “outsiders” in the worlds of welfare and electoral politics (Rueda 2005). Throughout this study, I seek to keep distinct the direct effects of labor laws in labor relations, on the one hand, and their indirect effects on economic and political incorporation, on the other. The focus here is on the former. But their impact on the latter cannot be denied, and will form an important part of the story told in the case histories presented in Chapters 4 through 6.

In addition, labor regulation is distinct from the economic policies or priorities of the sitting government. Leaders have a variety of mechanisms that they may employ to affect the labor market, ranging from subsidies to employers and control of monetary policy and exchange rates, on the one hand, to training programs or unemployment benefits for workers, on the other. The use of these policy tools is, of course, related to the labor law environment. But labor law is among the least wieldy mechanisms in the state’s arsenal for implementing policy; it often requires significant time to pass, and as will be seen below, it is among the slowest policies to change. Similarly, this study does not examine voluntary norms adopted by industries or groups of employers. While significant new initiatives have been taken by particular firms and industries in recent years, they constitute a fundamentally different object of study. And they are likely to be driven by a very different economic and political process than domestic laws that have passed through the state’s policy-making process.

In sum, this study examines written labor laws, whether passed by the legislature, executive, or judicial branches, that apply broadly throughout the national economy. In some cases, it also considers laws written to apply only to particular industries, especially in the early years of labor law development. This emphasis on written law allows for analytic clarity and precise comparison across countries and over time. And it permits careful tracing of the causal process that produces particular labor law configurations.

The Labor-law Policy Space

The comprehensive focus of this book requires carefully defining the labor-law policy space. Surprisingly, this has not been done in previous studies. Most comparative work has focused on examining a limited set of laws across a small number of cases, and thus it has considered particular laws detached from the overall labor code.1 Comprehensive analyses of labor codes as wholes—the combinations of labor laws that exist in a given country—are lacking. This fails to appreciate the ways that laws interact with one another. The legal environment has an impact on economic activity and political competition precisely through the combination of measures that exist. And workers, firms, and politicians are acutely aware of how specific measures can be traded off one for another. Greater job stability might be ensured, but with less expectation for regular wage increases because of diminished collective bargaining regulation. Or unions might be given a greater capacity to raise funds, but be limited in their ability to use those funds to underwrite strike activity. And individuals may be willing to accept longer hours or less overtime pay if they believe that stronger union rights will allow them to renegotiate such benefits in a future bargaining round. Understanding how legal measures fit together, and not just their individual stipulations, is crucial to understanding the politics of labor regulation.

In this section, I delineate the policy space in which labor law functions. After arraying legal measures across two dimensions, I develop a “conceptual typology” (Collier et al. 2012) of labor law regimes—consisting of different combinations of labor law provisions. This typology is a first step in understanding the variation that exists across labor codes. The subsequent section will develop a political theory of labor code variation.

Legal scholars distinguish two principal types of labor laws based on the area of labor relations that they regulate (Botero et al. 2004; Murillo 2005). I use these two types to construct the labor law policy space. First, provisions that cover the hiring, treatment, expectations, and firing of workers are called “individual” laws. These provisions cover the presumed duration of employment, working conditions, rest and leave po...