![]()

Part I

The Past

The emergence of new models of collective business leadership

Part I focuses on the past. Chapter 1 provides a brief overview of the rise of the corporate responsibility movement, which has been covered extensively elsewhere, and Chapter 2 gives a definition of business-led corporate responsibility coalitions. Chapter 3 focuses on three key stages in the evolution of these coalitions over the past four decades. Chapter 4 then highlights some of the global trends that have played a role in driving the growth of business-led corporate responsibility coalitions during this period and Chapter 5 reviews the role of individual champions, companies and foundations in supporting the creation and expansion of the coalitions.

![]()

1

The rise of the corporate responsibility movement

Corporate responsibility – in sum, the approaches that companies employ to embed environmental, social and governance (ESG) risks and opportunities into their core business strategies and operations with the aim of either protecting or creating shared value for business and society – is increasingly recognized as a fact of business life.

A 2010 Accenture study found that 93% of more than 750 CEOs surveyed globally believed that sustainability is critical to their future business success, and 96% said sustainability has to be embedded in business strategy and operations.20 McKinsey, in its 2011 sustainability survey, reported that more than 70% of over 3,200 company respondents from a range of industry sectors across the world said that sustainability is either a top three or priority item on the CEO’s global agenda.21Also in 2011, KPMG found that 95% of the world’s 250 largest companies report on corporate responsibility, concluding that corporate reporting on ESG performance is now de facto law in some countries.22 An academic study by Kolodinsky et al. in 2010 found that 90% of Fortune 500 firms embraced corporate social responsibility as an essential element in their organizational goals.23

The underlying drivers of corporate responsibility over the past three decades have been well documented. The ESG performance of business has become a more important issue as the processes of economic liberalization, privatization, globalization and technological transformation have opened up markets around the world and expanded the reach, scope and influence of the private sector, especially that of multinational corporations, whose numbers, according to UNCTAD, have grown from circa 60,000 in 2000 to over 80,000 today. As David Rothkopf points out in Power Inc., over the last few decades, the world’s largest private-sector organizations have grown dramatically in resources, global reach and influence:24

The world’s largest company,25 Wal-Mart Stores Inc., has revenues higher than the GDPs of all but 25 of the world’s countries. Its employees (2.1 million) outnumber the populations of almost a hundred nations. The world’s largest asset manager, a comparatively low-profile New York company called BlackRock, controls assets greater than the national reserves of any country on the planet.26

Simultaneously, the dramatic growth of information and communications technology and social media has enabled many more people around the world to learn about what is happening in previously remote locations or to become aware of issues that were known or noticed locally at best. It also means that these newly aware citizens can rapidly and effectively organize online campaigns against corporate behavior of which they disapprove. The continued growth of social media will only intensify the potential for viral campaigns against business misbehavior.

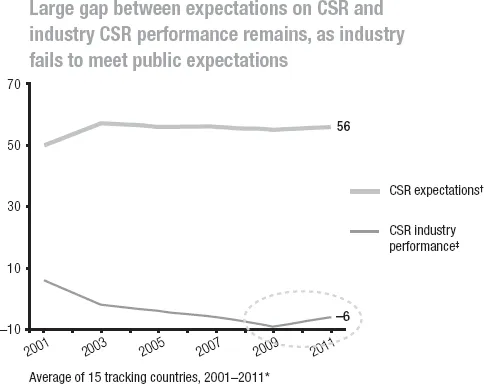

Corporate governance and ethics scandals and the global financial crisis have further undermined trust in business, especially in large corporations. As the Edelman Trust Barometer has tracked during 12 years of annual surveys, the corporate sector has a large, and growing, trust deficit to overcome in many countries.27 It also has to meet a large gap in expectations. GlobeScan – an international center for objective survey research and strategic counsel – has, since 2000, tracked the gap between popular views about how business should behave on corporate social responsibility issues and perceptions of how business is behaving.28 As Figure 1.1 illustrates, the private sector is failing to meet public expectations.

Figure 1.1 Expectations versus performance gap

Source: GlobeScan 2011

* Includes Australia, Brazil, China, France, Germany, Italy, Mexico, Nigeria, Russia, South Korea, Turkey, the UK and the USA

† Aggregate net expectations of up to 10 responsibilities of large companies (not all responsibilities were asked in each country each year)

‡ Aggregate net CSR performance ratings of 10 industries

The upper line is the aggregated figure of respondents expecting business to meet the basket of CR standards specified, and the lower line is the net aggregated figure of those respondents perceiving businesses to be meeting versus those not meeting these standards.

Underpinning all these trends has been growing evidence of climate change and natural resource depletion, and the role of business in exacerbating or addressing these challenges. The International Food Policy Research Institute has estimated that the demand for water will have increased by 30% by 2030 and that some two-thirds of watersheds will be stressed.29 The UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization estimates that food demand will have increased by 50% by 2030,30 while the International Energy Association predicts that demand for energy will have also increased by 50% by the same period.31

As the McKinsey Global Institute noted in its seminal report of 2011, The Resource Revolution:

The size of today’s challenge should not be underestimated; nor should the obstacles to diffusing more resource-efficient technologies throughout the global economy. The next 20 years appear likely to be quite different from the resource-related shocks that have periodically erupted in history. Up to three billion more middle class consumers will emerge in the next 20 years compared with 1.8 billion today, driving up demand for a range of different resources. This soaring demand will occur at a time when finding new sources of supply and extracting them is becoming increasingly challenging and expensive, notwithstanding technological improvement in the main resource sectors. Compounding the challenge are stronger links between resources, which increase the risk that shortages and price changes in one resource can rapidly spread to others. The deterioration in the environment, itself driven by growth in resource consumption, also appears to be increasing the vulnerability of resource supply systems . . . Finally, concern is growing that a large share of the global population lacks access to basic needs such as energy, water, and food, not least due to the rapid diffusion of technologies such as mobile phones to low-income consumers, which has increased their political voice and demonstrated the potential to provide universal access to basic services.32

The combination of growing demand, increased resource scarcity, volatility and risk, and stronger links and feedback loops between certain critical resources (increasingly referred to as the energy–food–water nexus) is putting growing pressures on ecosystems, social systems, economic systems and political systems. This has led to consequent demands, including from business itself, for more concerted and systemic efforts to improve water, energy and food security, and to achieve sustainable development more broadly. Research by McKinsey and others has “established that both an increase in the supply of resources and a step change in the productivity of how resources are extracted, converted and used would be required to head off potential resource constraints over the next 20 years.”33 New models of corporate responsibility and sustainability will be essential to achieving this step change, alongside and within an enabling framework of better government policies.

At the same time, the economic and human costs of the global financial crisis, high levels of unemployment and growing inequality of opportunity in many nations have added further pressure on the private sector to help address broader socioeconomic issues. The International Labour Organization (ILO) World of Work Report 2012 states that “more than 200 million workers will be unemployed in 2012,” with some 50 million jobs having been lost since the financial crisis began in 2008.34 According to the ILO’s Global Employment Trends 2012 report: “The world faces the ‘urgent challenge’ of creating 600 million productive jobs over the next decade to generate sustainable growth and maintain social cohesion.”35 The ILO estimates that one out of every three workers in the world is classified as unemployed or poor, and argues that young people and the low-skilled are bearing the brunt of the jobs crisis. Young people are three times more likely to be unemployed than adults and over 75 million youth worldwide are looking for work. The ILO warns of a “scarred” generation of young workers facing a dangerous mix of high unemployment, increased inactivity and precarious work in developed countries, as well as persistently high working poverty in the developing world.36 Growing inequality is also a problem in many countries. In the United States, the share of national income going to the upper 1% more than doubled from 1979 to 2012, from about 10% to about 23.5%.37 According to the Economic Mobility Project of the Pew Charitable Trusts, only one-third of American families will surpass their parents in wealth and income and climb to a new rung on the economic ladder.38 Similar patterns of high unemployment and declining equality of opportunity are being repeated elsewhere and they put increasing pressure on the private sector to play a more proactive role in working with governments to find solutions.

Another important driver of corporate responsibility over the past decade has been a growing focus on the responsibilities of business, especially large corporations, in relation to human rights. In 2005, following a series of well-documented cases of companies being responsible for or complicit in human rights abuses, the former UN Secretary-General, Kofi Annan, appointed Professor John Ruggie to serve as his Special Representative on Business and Human Rights. This was the first time in the history of the United Nations that such an appointment had been made to focus specifically on the role of the private sector. In 2008, after three years of extensive research and wide-ranging consultations around the world with governments, business associations, companies and civil-society organizations, Professor Ruggie proposed a framework to clarify the relevant actors’ responsibilities in relation to human rights.

This framework, now referred to as the UN Framework on Business and Human Rights, and popularly called the “Protect, Respect, Remedy” Framework, was unanimously welcomed by the UN Human Rights Council. It rests on three pillars: the state duty to protect against human rights abuses by third parties, including business, through appropriate policies, regulation and adjudication; the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, which means to act with due diligence to avoid infringing on the rights of others and to address adverse impacts that occur; and greater access by victims to effective remedy, both judicial and non-judicial.39

The Special Representative’s mandate was extended until 2011 to develop more operational guidance on how to implement the Framework, and in June 2011 the UN Guiding Principles were unanimously endorsed by the Human Rights Council. Professor Ruggie notes:

we now ha...