![]()

1

The Jaffa Powerhouse

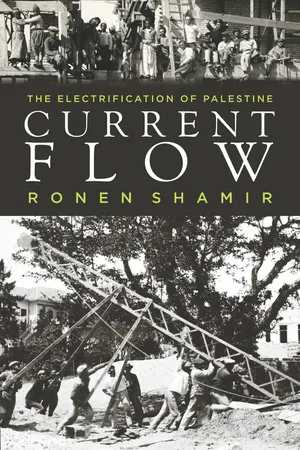

ON JUNE 10, 1923, a ceremonial photograph (Figure 1) was taken at the newly built powerhouse of the Jaffa Electric Company (hereafter the Electric Company or the company). Built in the best and latest high-tech architectural style, the powerhouse was located on a 5-acre (20-dunam1) lot somewhere along the eastern part of the loosely defined boundary between Jaffa and the small Township of Tel Aviv. Electricity first flowed through the electric grid to the two main streets of Tel Aviv on this day. Carried through low-tension cables, electrical power traversed from the transformer to 40-, 100-, and even 200-“candlepower” (watt) streetlamps. In the center left of the photo stands Pinhas Rutenberg, entrepreneur and chairman of the board of directors of the Jaffa Electric Company, dressed in spectacles and an open black jacket and tie.

The ceremonial lighting of the two main streets of Tel Aviv realized the first operational results of the Auja Concession, which had authorized Rutenberg to generate electricity by means of hydroelectric turbines that would exploit the water power of the small Auja River (the Yarkon in Hebrew) to supply electricity to Jaffa (1923 population: 55,000), the smaller neighboring town of Tel Aviv (1923 population: 16,000), and other locations within the bounds of the administrative District of Jaffa. Article 3 of the Auja Concession stipulated that the concessionaire would build a hydroelectric “generating station or power house in the neighborhood of Jerishe to be called the Yarkon Power House.”2 Among many other things, the concession created an obligation on the part of concessionaire to complete all works and to begin operations by September 1923.

FIGURE 1 Pinhas Rutenberg and staff at the opening ceremony of the Jaffa Electric Company powerhouse, June 10, 1923

SOURCE: BNA CO 1069/731.

NOTE: This photograph is part of an album documenting the construction of the Jaffa powerhouse. The photographs were all taken by Z. Brill, a professional photographer who was hired by the electric company for that purpose. The album was presented to the governor of Jaffa and currently can be found intact in the British National Archives.

Yet the plan to generate electricity by hydroelectric means never materialized, and instead Rutenberg steered the company to design and build a powerhouse that produced electricity by means of diesel-fueled engines. The powerhouse was built miles away from the original designated location, in an area between Jaffa and Tel Aviv (Ram 1996). Rutenberg justified the shift in location and technology in terms of the political conditions pertaining to the electrification of Palestine. He explained that he was diverted from his original plan by the unreasonable financial demands of recalcitrant Arab landowners in the Auja basin, who had joined forces with an all-Arab collective struggle against the British decision to grant Rutenberg his concessions. The British authorities accepted this explanation, as have latter-day historians.3

Though British electric companies did not foresee any commercial value in the electrification of Palestine, the decision to grant the concessions to Rutenberg was nonetheless a product of imperial policies. The British had taken Palestine from the crumbling Ottoman Empire toward the end of World War I, and their foothold in the region received international backing through colonial agreements with France and later through a Mandate of the League of Nations. The Mandate expressed the British commitment to promote the necessary conditions for establishing a “Jewish National Home” in Palestine, along with a general obligation to develop the country for the benefit of all its inhabitants. The commitment to promote a Jewish National Home was particularly significant considering the demographic profile of the country at the time: 643,000 Arabs and 84,000 Jews according to the 1922 census. The grant of the concessions to Rutenberg (and to the Zionist institutions that provided financial backing to the electric companies he established) functioned as an economic medium for advancing imperial interests: they were portrayed by the British both as means for economic development of the country (and hence an instrument for pacifying ethno-national tensions) and as a market-based means for promoting the Jewish National Home without resorting to controversial political steps.

British hopes to neutralize the political implications of granting the concessions to Rutenberg were disappointed. The political and financial backing for the electrification plan came almost exclusively from Zionist organizations and Jewish philanthropists—the London-based Jewish Colonial Trust and the Palestinian Jewish Colonization Association (funded by Rothschild). Rufus Isaacs (Lord Reading) sat on the board of the Palestine Electric Company as the representative of several British trust associations, and other notable British Jewish funders included Sir Alfred Mond (Lord Melchet) and Michael Nassatisin. The Anglo-Palestine bank, a major financial arm of the Zionist movement, was also involved in financing the scheme.4 In turn, the financial and political backing of the Zionist Executive in London and influential Jewish British figures served as a highly useful bridge to key British policy makers.5 Consequently, the grant of the concessions to Rutenberg met fierce public and diplomatic resistance from Arab leaders, who feared that the electrification scheme would allow the Jews to obtain “a stranglehold on the economic life of Palestine and Transjordania.”6 The construction of a powerhouse and the appearance of electric poles in Jaffa two years later served to corroborate these fears and triggered various public displays of Arab national sentiments. The suggestion that “Arab agitation” in general and recalcitrant Arab landowners in particular prevented Rutenberg from building an electric powerhouse on the Auja was therefore in line with the political reality of the times.

Nevertheless, this chapter finds that while Arab agitation was real, it mainly served as a discursive trope for justifying a decision prompted primarily by commercial considerations and the technological imperatives of machines. Arab agitation—neither in the form of recalcitrant landowners nor, more broadly, in the form of organized public and political opposition—did not determine the location of the powerhouse and the technology used for generating electrical energy. Neither did some presumed Zionist master plan. Rather, deliberations over location and the technology for producing electricity were an occasion for various ethno-national performances: asserting national concerns in newspaper articles and public speeches, associating electric light with matters of national pride or otherwise national humiliation, and scripting the relations between Jewish Tel Aviv and Arab Jaffa. The “concrete” process that solidified an attachment between electricity and ethno-national identities, in other words, should be looked at on a par with the “context” of relations between the colonial state, local governments, and the Arab and Jewish populations of Palestine.

But all this will come later. The powerhouse had just been completed, and the very process of its design and construction should give a first idea about the type of sociology that may be extracted from following the assembly of an electrical infrastructure.

A First Circuit: London, Jerusalem, and the Construction of a “Political Context”

Here, then, is this techno-political issue of Arab agitation. It is made of a set of connections whose materiality mainly consists of traces left behind by the circulation of requests and statements of appeal, confidential memoranda, government minutes, legal opinions, and various other textual forms. These documents flowed in the form of letters, hand-delivered notices, dispatches, and telegraphs mainly between Jerusalem and London, involving correspondence between Pinhas Rutenberg; High Commissioner Samuel and later High Commissioner Plumer; Secretary of State for the Colonies Winston Churchill and his successor in office, Leo Amery; Zionist officials and Jewish financiers; technical experts and electrical engineers; and a considerable number of officials in the Colonial Office and in the law offices of the Royal Courts of Justice.

Yet so-called Arab agitation was only one of many issues moving back and forth between London and Jerusalem. Among other things, there was the techno-political issue of Germany’s electrical capabilities. While Arab-Jewish relations were mainly invoked at this point with respect to where to locate the powerhouse, British-German relations came to life over the question of who would assume a leading role in providing materials and technology for the electrification project.

The circulation of policy documents, legal proposals, and technical schemes regarding such issues were strongly personified in the international travels of Pinhas Rutenberg himself. Soon after being granted the concession, in September 1921, Rutenberg embarked on a trip from London to Jaffa with the intention of entering “into negotiations for the acquisition of land required for the Auja project” from Arab landowners.7 He returned to London in late December 1921 and was soon off to Berlin to consult German electrical engineers and to negotiate the purchase of German machinery. On his return to London, sometime in mid-January, he received a letter, urgently hand-delivered by his brother Abraham,8 from his lawyer and most intimate and faithful legal advisor, Harry Sacher. Having heard of Rutenberg’s decision to build a diesel-fueled powerhouse, Sacher warned against the idea of dropping the plan to build a hydroelectric station on the Auja River. He minced no words and composed a carefully reasoned three-page letter, dividing his arguments into “financial” and “legal-political” aspects.

The financial aspect concerned the fact that Rutenberg wanted to purchase 150 dunam (roughly 42 acres) in the Auja, for which the Arab landowners asked £259 per dunam, bringing the estimated total cost to £3,750. Sacher concurred that the price was burdensome, yet reminded Rutenberg that they had also planned an alternative hydroelectric scheme that would have required the purchase of only 25 dunam. Besides, Sacher wrote, they had already spent considerable sums in preparing the plans, and “if the Auja scheme is dropped and fuel stations are substituted, then I would imagine that most of this money would be wasted.”

Then came the legal-political considerations, which apparently were graver than the financial ones. “As you are well aware,” wrote Sacher, “the Auja concession is for hydro-electricity and your right to erect [a] fuel plant is simply supplementary to your right to make use of the water of the Auja.” In other words, “the setting up of a fuel station and the consequential abandonment of the hydro-electric scheme would, in effect, mean the dropping of the whole Auja Concession.” Sacher concluded that Rutenberg would then have to negotiate a new concession and, horrified, he wrote that “as your legal adviser I cannot contemplate you with equanimity beginning all over again the negotiations.” He warned Rutenberg that in all likelihood the British Government would not grant him a new concession because of the political circumstances that led to the granting of the original one: “The Government looks upon the Auja enterprise as a link to co-operation between the Jews and Arabs. If you were to drop it now, it would be a confession of failure which would have a deplorable appearance and effect.”10

Sacher added another “political” consideration that proves important in tracing the connections that would lead to the fuel powerhouse. He reminded Rutenberg that the Municipality of (mostly Arab) Jaffa “approved of the Auja hydro-electric scheme” and cooperated in negotiating a supply contract. Dropping the scheme, especially if interpreted as a political failure, might drive the municipality to retract its approval. “A very grave blunder can now be made,” Sacher concluded. “Your advisers in London and Berlin may have influenced you to reach a mistaken decision . . . and it is our duty to do everything to prevent it being made.”

Yet, in spite of Sacher’s dire warnings, Rutenberg was able to change course without losing the concession. In fact, by the time he received his lawyer’s letter he was already busy placing orders for machinery from Germany and finalizing the plans for erecting a fuel power station. Moreover, while Sacher worried about a scenario that would link the technological change to the problematic political issue of Jewish-Arab relations, Rutenberg deployed the very same issue in order to pursue his new plan.

A string of documents and letters from the Electric Company, the first of which is dated July 24, 1922, and addressed to the Undersecretary of State for the Colonies in the Near East Department, provides an opportunity to trace the way in which the link between technology and politics furthered the move away from the hydroelectric plan.11 This first letter does not announce the dropping of the hydroelectric scheme. It does not even ask for a postponement. Rather, it suggests a way to legally construct Rutenberg’s actions as if work toward a hydroelectric scheme had actually begun: “I left for Palestine with the intention of acquiring land for the Auja Scheme,” Rutenberg began, but “the prices demanded by the owners of the land were out of all proportion to the market prices.” Article 14 of the concession authorized the Government, under certain conditions, to expropriate needed land and installations and to pay owners “fair” compensation to be financially borne by the concessionaire. However, Rutenberg explained that, for political reasons, “I agreed with the Government” that it was inadvisable to do so. Rather, “I decided to build a fuel power station in Jaffa,” he wrote, with the expectation that work would begin in August 1922 and conclude by January 1923 (eight months prior to the date set in the concession for finalizing the hydroelectric station on the Auja River). Moreover, “in view of the fact that energy will thus be provided before the time stipulated in the concession, I respectfully beg to request you to consider the building of the fuel powerhouse as the commencement of work within the meaning of the concession and release me from the commitment to finish the hydro-electric station until September 1923.” Not having to work under the pressure of time, Rutenberg concluded, “I shall be able to soon reach amicable arrangements with the owners of the land on the Auja.”

The concerns of his lawyer notwithstanding, Rutenberg expressed no intention of waiving the Auja Concession when he decided to build the powerhouse. And his plan worked. No apparent “grave blunder” followed. The Office of the High Commissioner secured the consent of the Colonial Office and responded within two days, welding diesel and hydroelectric technologies through a new contractual understanding: Rutenberg would finish the fuel powerhouse by January 1923 and in exchange would not have to commence work on the hydroelectric station until September 1923.12 From then on—for a number of years stretching well beyond the completion of the powerhouse and in tandem with its extensive and ever expanding electric grid—Rutenberg used each new request to extend the date for commencing the hydroelectric project as a medium of change, as a means to make slight yet meaningful modifications in the type of connections between the construction of the fuel powerhouse, the concession, and the suspended construction of the hydroelectric statio...