![]()

1

Historical Aliabad

BY NOW, Shiraz and Aliabad have both expanded so that they all but meet. In 1978, though, Aliabad was half an hour by bus, some 35 kilo-meters, from the outskirts of Shiraz. The city of Shiraz had been built up a ways out on the road leading to Aliabad, with lovely residential areas and then walled-in gardens and orchards as one traveled toward Qasr el-Dasht on the outskirts of the city. Buses loading up to go to Aliabad and other settlements in the same direction waited near the Qasr el-Dasht square until they were filled with passengers. People could do some last-minute shopping for fresh fruit and vegetables at the outdoor shops near the square, as well as for other items in nearby stores. When the bus was finally out of the city, the scenery turned plain, with dry stony ground between ranges of hills lining either side of the highway. The skyscrapers of the Hossainabad housing project just outside Shiraz, where several Aliabadis had found construction work, caught one’s attention. Even in 1978, traffic was heavy, in part because of the presence of several factories between Shiraz and Aliabad. Large trucks sped along, bringing gravel to the city from the two gravel pits on Aliabad land. Moving further up the valley, one saw high rocky crags in the distance. The bus stopped at several factories to let off workers, who walked the rest of the distance off the main road to their work sites. The village of Qodratabad lay on the left, with its gendarmerie station not far off the paved highway, and then only two kilometers further on was Aliabad.

Aliabad

Aliabad is located in a valley that not many decades ago was populated by villages of riyat (sharecroppers). The province of Fars produced wheat, barley, rice, cotton, sugar beets, fruit, dates, legumes and vegetables. By 1870, opium had become an important crop, although its cultivation was banned in 1955. Grape varieties from the region were famous and included those used to produce Shiraz, Syrah and Sirah wines. As is much of Iran, Fars is arid and hot in the summer. Although dryland agriculture was also practiced in Aliabad and other villages in the area, irrigated land of course produced much more. Water sources were valuable and often the subject of contention. Before land reform in the 1960s, most of the area was under the control of the absentee Qavam family landlords. Cultivation was carried out by means of animal and human power, with produce divided between landlord and peasants. The riyat and their families in Aliabad and the other villages in the region lived in what would be seen by middle-class Western eyes as severe poverty.1 Modern roads and transportation, education and health facilities, plumbing, electricity, and natural gas for heating and cooking came to Aliabad only in the 1950s and 1960s, although this was sooner than in many other Iranian villages. Animal products were also significant in the regional economy, both for villagers and even more so for nomadic tribal groups, who shepherded their flocks up and down mountain slopes depending on the season. People of Aliabad and other villages in the area interacted with the various tribal groups making their home in Fars province, such as Qashqai and Lurs, as trading partners, political allies or victims of bandits preying on itinerant traders walking between villages, or even of large tribal groups taking over control of the village before political centralization in the 1950s and 1960s.

When I approached Aliabad, a village of about 3,000 people, for the first time in 1978, I could see several rows of new houses and their courtyards, with construction still proceeding on new additions, to the right of the highway. On the left stood the high-walled, square-shaped old village with a tower rising up at each of its four corners. The bus stopped near the entrance to the old village, where quite a few men and boys generally sat enjoying the sun and the opportunity to catch up on village affairs and news from Shiraz. A few vehicles in various stages of repair and several shops, such as a “coffee house,”2 welding shop, motor repair shop and bread bakery, as well as an old, rundown shrine, were just outside the village gate. Further on, just past the village wall, another small residential area had been built some seven or eight years earlier. The village cemetery and the little building for washing bodies before burial lay to its left. On the right side of the highway, just past the large residential area with its rows of recently built homes, were several government buildings: health center, post office and school. Beyond these and further away from the highway lay the main shrine of the village, Seyyid Seraj,3 with a little road providing access and surrounded by another, smaller cemetery.

Anyone entering the village gate would first go through a passageway lined on either side by four or five rooms, each with a corrugated metal door pulled down and padlocked. Prior to land reform, these rooms were used to store the grain produced in the village before it was transported to the landlord in Shiraz, and to keep seed for the following year. The rooms were also used as a prison for recalcitrant peasants. Just inside the passageway, large Pepsi and Coca-Cola signs marked two or three minimal grocery shops edging the large, open area. Here men often gathered to sit in the sun and talk. The mosque courtyard lay just to the right of this square. Leading off this open area were several little alleyways. The main one formed a circle around the village. Subsidiary alleys branched off from the main alley to give access to all homes. A small ditch for disposing of waste water ran through the center of each alley. Walking through the alleyways, one could catch glimpses through courtyard doors of activity within, such as women washing dishes or clothes at the courtyard water spigot.

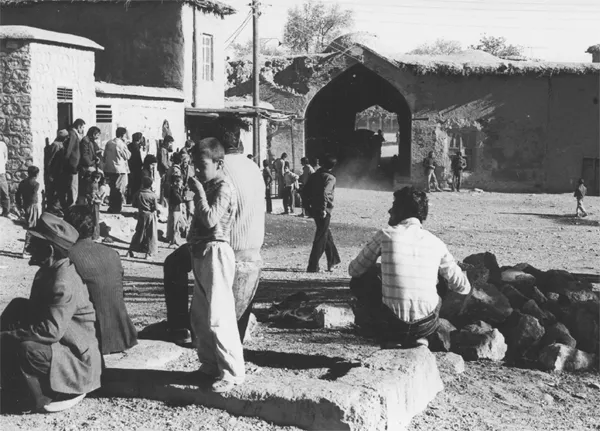

FIGURE 2. Men and boys hanging out in the large open area just inside the entrance to the walled village of Aliabad. The sunshade of Haj Khodabakhsh’s shop (see Chapter 5) is on the left, and the entrance to Kurosh Amini’s courtyard (see Chapters 4 and 5) is to the right of the village entrance. Photo from 1978–1979.

Although the “new village” homes across the highway were built of fine-looking fired brick, homes in the old village were constructed of sun-dried mudbrick plastered with mud. The color of the mud-covered buildings together with the dusty, plain appearance of the alleyways gave a drab look to the interior of the village. I remember watching dirt and scraps of paper tossed up by wind gusts and feeling rather dismayed at the thought of living there for a year and a half.

Several Aliabad residents told me the history of the settlement. It had been decimated by the Mongol invasion in the 13th century. Over time, people—many from the surrounding areas—immigrated in and out.

According to local historians, at some points it contained some 8,000 households. For the last 200 years, people told me, Aliabad had been a large village and an important political, market, cultural and religious center. Persons trained in religion and religious law who had long ago emigrated from Bahrain to Aliabad had directed the mosque and Qoranic school. Aliabad, along with most other villages in the Shiraz area, became the tax farm of the Qavam family of Shiraz, though not without some resistance, villagers told me.

Later, many tax farmers—the government tax-collectors of agricultural areas—took over as their own private property the villages from which they were supposed to collect tax revenue for the government.4 In Aliabad too, the head of the Qavam family was able to take ownership by force. Stories have been passed down of men tied up and beaten or taken to Shiraz and put in chains in the Qavam effort to gain possession of the village. In Aliabad, this process apparently took place 100 years or more before my 1978–1979 fieldwork.

Informants talked about the great power of the Qavams and how for some hundred and fifty years the current head of the Qavam family had controlled the regions of Darab5 and Fasa and acted as the “shah” of the region from Shiraz to Bandar Abbas. They owned at least 50 villages similar to Aliabad, people reported. According to one informant, there had been three “shahs” in the region: Qavam, Qashqai and Shaikh.6

Reza Shah—the father of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi—who ruled Iran from 1925 to 1941, wanted to cut back the power of such regional political figures and bring the country under centralized political control. In the 1930s, Reza Shah abolished the office of mayor of Shiraz, held by Ibrahim Khan Qavam, who had controlled Aliabad. Ibrahim and his family were exiled to Tehran for a time,7 as was the head of the Qashqai tribespeople, Solat ed-Doleh Qashqai. One complaint against Ibrahim Qavam was that he acted like an independent power and cooperated too closely with the English. Later, though, he regained the favor of the central government, which was concerned about Qashqai power in Fars. Ibrahim Qavam was appointed governor-general of Fars in 1943 and provided with rifles to distribute among the Khamseh tribesmen.8 At some point, Aliabad was given over to Khanum Khorshid Kolah Qavam, sister of Ibrahim Qavam and daughter of Habibollah Qavam ol-Molk.

The villagers of the next village, Darab, could relate even more vivid tales about the period several decades after the Qavams took over ownership of Aliabad, when Nazem ol-Molk, Khanum Khorshid Kolah’s husband at the time, came with a retinue and tented outside Darab. Nazem ol-Molk wanted to forcefully take over ownership of his tax farm. The struggle continued for some time in Darab, with members of the Qavam family, Nazem ol-Molk and his wife, Khanum Khorshid Kolah, attempting to use internal factionalism and gaining the support of a poorer group who owned no land or orchards to obtain control of Darab. The members of this minority faction were willing to cooperate with the Qavam outsiders in the struggle against the dominant faction. They hoped thereby to serve their own interests through taking over as the socioeconomic and political village elite. Sometime between 1935 and 1938, a number of Darab villagers were killed, and Khanum Khorshid Kolah was able to appoint a kadkhoda and a bailiff and enforce the giving of one-sixth of dryland crops and one quarter of irrigated crops to her as landlord. But the matter was not settled conclusively, and for another 30 years or so the conflict continued, with eruptions of violence every few years.

After Nazem ol-Molk died, Khanum Khorshid Kolah married Asadollah Khan Arab Shaibani—“Arab”—who had been the Qavams’ bailiff for Aliabad.9 The Qavams owned the large building in Aliabad that housed the government kindergarten in 1978–1979. When Khanum Khorshid Kolah came to Aliabad for a visit accompanied by a retinue of some thirty horsemen, she stayed in that building. Seyyid Ibn Ali Askari, who became the largest landowner in Aliabad after land reform, later bought this building from the Qavams. Seyyid Ibn Ali lived there with his family until the hostility of other villagers during the 1962 land reform conflict forced him to move to Shiraz. Khanum Khorshid Kolah also owned the house and courtyard that in 1978–1979 was home to Seyyid Ibn Ali’s brother, Seyyid Yaqub Askari. Together the two brothers controlled village affairs, with Seyyid Ibn Ali residing in Shiraz, before the Iranian Revolution of February 1979.

Before the 1950s and 1960s, half or more of the working force of Aliabad, at least 200 men, engaged primarily in agriculture. Another 200 villagers worked primarily in trade. Others filled the specialties required by the local population, such as carpenter, shepherd, bath attendant, barber, blacksmith, guard of the vineyards, guard of the fields and religious specialist. Ten or more men were shoemakers, sewing the tough, handmade shoes with crocheted cotton uppers and leather—later rubber tire—soles worn by villagers and especially valued by migrating tribespeople because of their durability. Only some ten men practiced migrant labor, journeying to Abadan to work for extended periods in the oil industry. Women were not expected to work outside the domestic environment but kept busy in their own courtyards. Agricultural families kept animals, and women took responsibility for them in the courtyard, feeding chickens and milking goats, sheep and cows, as well as preparing milk products and preserving other foods. Widows were often forced to work to support themselves and their children and might go out to camps of migrating tribespeople to trade.

Khanum Khorshid Kolah continued to be the owner of Aliabad until land reform in 1962. Ibrahim Qavam died in 1969.10 His two sons, Ali and Mohammad Reza, and his daughters lived in Tehran in 1978. Khanum Khorshid Kolah died in the early 1970s. Her husband Arab Shaibani, who had also served as her agent, died at about the same time. Although the former landlords of Aliabad were no longer in the picture when I came in late summer 1978, their ownership of Aliabad and the taifeh-keshi political system in operation during their time were recent enough that oral history interviews could shed light on them.

Political anthropology had become one of my main interests before I went to Aliabad for field research. To study political anthropology, which typically deals with local politics and the connections between national and local politics, I should talk with men, I assumed. I owe it to the revolutionary turmoil and to periods when, with few exceptions, men would not talk with me—a suspect American in their midst—that I was forced to start asking women about their activities and observing their interactions with others, and began to realize the unique roles women played in politics. I questioned them about engagements, weddings, cooking and distributing food in the name of holy figures, mourning ceremonies, women’s visits and gifts when a daughter became pregnant and then gave birth, and women’s many other formal and informal visits and exchanges. Through observation and asking questions, I became aware of women’s lively socializing and networking, which helped keep political alliances active, and of the close relationships between women and their families of origin—which could provide men with more political clout to protect people and resources, as well as alternative alliances in case men deemed it best to shift allegiance to another coalition of taifeh. Then, when taifeh-keshi emerged again during the revolutionary upheaval, I was better prepared to understand the parts of both men and women. Men’s and boys’ public actions of violence were more visible and dramatic—and resulted in outrage and extensive discussion. Women’s part in politics was less apparent but went on as part of everyday social life before, during and after eruptions. Without being sensitized to the political aspects of women’s lives, I might well have overlooked a crucial part of taifeh-keshi politics in village history—political relations through women and women’s political work—and then in the Revolution and the post-Revolution local uprising.11

Bilateral Kinship and Political Alternatives in Aliabad Taifeh-Keshi

Much of the flexibility of taifeh and the ability of men to shift from one taifeh to another to best serve their own and their families’ interests was based on the bilateral kinship system: in Aliabad as elsewhere in Iran,12 children are considered equally related to their mother’s and father’s families. The nuclear family is primary, and a woman is considered to be a member of her husband’s household rather than her father’s. Beyond the nuclear family, almost equal importance is placed on ties through both men and women, rather than only on patrilateral (through the father) kinship.

In Aliabad, matrilateral (through the mother) and affinal (in-law) ties held weight: in-laws were called relatives. Wedding celebrations were held at the home of the bride as well as at the home of the groom, indicating the significance of the bride’s family in social and political alliances.

In form (or rather lack of fixed form), the Aliabad taifeh system resembled the kinship system commonly found in other Iranian communities, urban as well as rural, which is characterized by indefinite boundaries, alternative ties, leadership yet interaction among members, flexibility a...