![]()

1 Enter the Dragon

“China is an awakening monster that can eat us.”

Carlos Zúñiga, Nicaraguan CAFTA negotiator

La Prensa (Nicaragua), March 10, 2004

“What are the factors driving the crisis of the textile sector? First is the global competition of China, which is more and more present in every market.”

Isaac Soloducho, president of Paylana, a leading exporter of high-quality wool-based apparel in Uruguay

El Observador (Uruguay), November 20, 2006, p.13

There is a growing clamor in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) over the extent to which the region is being economically swallowed by China. Some claim that China's exports are flooding domestic LAC markets and wiping out local firms. Others refer to China as an “angel” for the region that will deliver the fruits of growth by importing LAC goods and investing in the LAC region. Yet there is no contention at all in LAC (or anywhere else) that China's export-led economic expansion since the early 1980s has been anything short of a miracle.

Amid all this chatter, what is strikingly absent from the discussion is a clear understanding of how China is globalizing its economy and what lessons that method might lend to the conundrum of economic development in LAC. Yes, China's growing appetite for primary products, and the ability of Latin America to supply that demand, played a role in restoring growth in Latin America, both in the run-up to the global financial crisis and in its aftermath. Yet, the dragon in the room that few are talking about is that China is simultaneously out-competing Latin American manufactures in world markets—so much so that it may threaten the ability of the region to generate long-run economic growth. What receives even less attention is that China's road to globalization, one that emphasizes gradualism and coordinated macro-economic and industrial policies, is far superior to the “Washington Consensus” route taken by most Latin American nations, particularly Mexico. And if LAC does not change its development strategy, many of the region's deepest fears could come home to roost. China may not be the problem, LAC's policies may be. China's rise may be able to offer clues for a better path.

This book is an attempt to confront these conversations head-on. We conduct a thorough analysis of China's economic relationship with LAC as well as an analysis of China's trade-led industrialization strategy.1

Specifically, we ask the question “To what extent has China's rising economic expansion benefited LAC countries?” We answer this question by looking at the bilateral trade that has blossomed between China and LAC in recent years. We also examine the competitiveness of LAC manufactures exports in world and regional markets relative to China. This exercise leads us to four central findings.

• LAC exports to China are heavily concentrated in a handful of countries and sectors, leaving the majority of LAC without the opportunity to significantly gain from China as a market for their exports.

• China is increasingly outcompeting LAC manufactures exports in world and regional markets, and the worst may be yet to come.

• China is rapidly building the technological capabilities necessary for industrial development, whereas LAC is not paying enough attention to innovation and industrial development.

• These three trends could accentuate a pattern of specialization in LAC that will hurt LAC's longer run prospects for economic development.

Our findings, which confirm and expand upon most of the recent peer-reviewed literature, imply that neither a hysterical fear of China nor optimistic complacency have much justification across the region. What is more, when one confronts the dragon in the room, we learn that China's rise is both a warning sign and an opportunity for LAC. China's rise is the latest warning to LAC that it cannot sit back with a laissez-faire attitude about economic policy and hope that such an attitude will automatically translate into growth and prosperity. China's rise is an opportunity because China's direct and indirect impacts on LAC exports will allow a handful of countries in the region to build reserves and bolster the region's fiscal position, enabling LAC to rekindle a serious discussion about industrial development for the twenty-first century.

Two Globalizations

Development derives from a process of diversifying an economy from concentrated assets based on primary products to a diverse set of assets based on knowledge. This process involves investing in human, physical and natural capital in manufacturing, and services (Amsden 2001, 2-3). Imbs and Wacziarg (2003) have confirmed that nations that develop follow this trajectory. They find that as nations get richer, sectoral production and employment move from a relatively high concentration to diversity. They find that nations do not stabilize their diversity until their populations reach a mean annual income of over $15,000. The question for development and trade policy then becomes “What policies will help facilitate the diversification and development process without conflicting with trade rules or jeopardizing the needs of future generations?”

The answer to this question will differ across the developing world depending on the particular binding constraints that a country's growth trajectory faces. The development policies for a small, vulnerable nation such as Haiti will be significantly different from countries like Brazil, India, and China, which may be looking to diversify beyond primary products and light manufacturing to high-tech manufacturing and services-based economic growth that develops endogenous productive capacity. Recent work in development economics shows that nations need to engage in a process of “self-discovery” whereby they undergo a diagnosis of what the binding constraints to economic growth may be (Rodrik 2007).

To some extent, China and LAC went through a diagnostic period just over thirty years ago. After such a process, both China and most of the countries in LAC determined that one of the binding constraints on their economic development was a lack of appreciation for markets in general and the world economy in particular. Although LAC is, of course, capitalist and China has remained socialist at least on paper, LAC and China have had similar goals over the past thirty years. Thirty years ago, both China and LAC were largely practicing a government-led economic policy that shied away from the world economy. In both China and LAC there were signs that such an approach had run its course. As we show in greater detail in chapter 6, both China and LAC sought to reform themselves by embracing markets in general and the world economy in particular. In 1978 for China, and 1982 for LAC, both places began to dismantle many of the vestiges of their old economic ways in favor of exports, foreign direct investment, and freer markets.

That is where the similarities end, however. LAC's approach to globalization has infamously been referred to as the embrace of the “Washington Consensus”—the fairly rapid liberalization of trade and investment regimes and the general decrease of the role of the state in economic affairs. Beginning in the early 1990s, LAC nations began to rapidly dismantle the role of the state in economic affairs. Although, of course, there are significant differences between countries, generally speaking LAC unilaterally privatized the majority of its state-owned enterprises, liberalized trade and investment, and limited government activity in macroeconomic policy, then locked in these reforms through joining the World Trade Organization (WTO). Some countries went even further in locking in these reforms by adopting the disciplines contained in free-trade agreements with the United States and other developed countries.

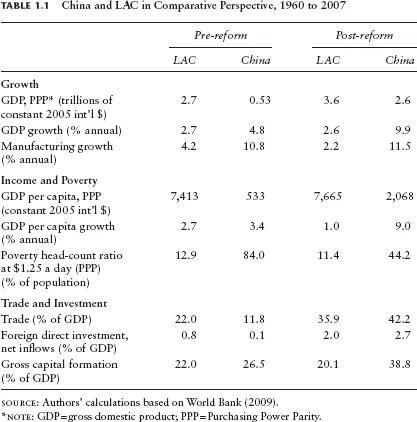

As we detail in Chapter 6, China's approach to globalization could not be more different. In contrast to the “shock therapy” practiced in LAC, China has globalized by what Deng Xiaoping said was “crossing the river by feeling each stone.” China's more gradual and experimental approach to reform allowed for the development of domestic firms and industries before liberalizing fully. More importantly, it also created an environment so that the potential “losers” from liberalization would be less numerous. Finally, China has shied away from trade deals with the United States and has focused more on the more multilateral WTO, which it joined in 2001. The results, shown in table 1.1, are stark.

Table 1.1 covers the period 1960 to 2007. For LAC the “pre-reform period” runs from 1960 to 1982, for China from 1960 to 1978. LAC started out with a higher GDP, a higher level of income, fewer people in poverty, and higher levels of trade and investment. And in terms of growth in income, LAC as a whole still remains much richer than China. Yet what jumps out in this table is that LAC has barely gained ground during its reform period, and China has excelled.

By every measure China has outreformed and outperformed LAC. Whereas LAC's GDP growth since reforms has been 2.6 percent annually and only 1 percent in per capita terms, China's growth has been an unprecedented 9.9 and 9 percent respectively. Whereas LAC still has many fewer people in poverty than China does, China has decreased the number of people in poverty (in the order of hundreds of millions) by half, and LAC by just over 10 percent, one percentage point. And when it comes to indicators of globalization itself—trade and investment—China trades more and outperforms in terms of investment.

All is not rosy in China, however. The environmental costs of China's growth miracle are of grave concern. China has become the world's largest emitter of carbon dioxide, and it is also riddled with contaminated water supplies and localized air pollution (Economy 2004). In addition, inequality has become a concern on China's booming eastern coast.

Of course, LAC does not need to compare itself to China. In many ways, when China reformed, it was starting out much further behind than LAC. What matters most is how LAC is faring in general. Looked at on its own, LAC growth is lackluster but not terrible. In contrast with sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia, growth has been positive, and, with the exception of the years during financial crises, poverty has not increased.

What does call for attention, however, is the extent to which China affects LAC's longer-term prospects for development. Will China's extraordinary growth spill over to LAC, or will China attract investment and trade that will divert from LAC? These are the questions we dwell on in this book.

Book Overview

This book examines the extent to which China's rising economic expansion has benefited or damaged LAC countries and draws implications for the future. We take an empirically based approach to this question from a number of angles. Throughout this volume we analyze the bilateral trade relationship between China and LAC countries, and the extent to which China and LAC compete in world markets. We want this work to be accessible to policymakers, students, and academics outside the economics profession, as well as to economists. For that reason, we have transferred the details of our methodological approach to a technical appendix in the back of the book so that the reader can get a crisp and clear understanding of our findings and their implications. Aside from the appendices, the volume has six chapters. Even with the appendices in the book, the reader may find some parts of the chapters to be fairly dense. Given how underresearched this area is to date, we make scores of calculations to answer our research questions. We have streamlined them to the extent we could, but discussion of the most important calculations is unavoidable. Taken together, this effort tells a story that is important for researchers and policymakers to understand. That said, this first chapter very briefly introduces and outlines our research and findings and puts them in context.

Chapter 2 performs a detailed analysis of the bilateral trade and investment relationship between LAC and China. In this chapter we calculate the levels of China-LAC trade. We find that China has had a positive impact on LAC through this channel in two ways. First, China's rise has led to an increase in demand for LAC products. Since 2000 China's imports from LAC have quintupled, reaching close to $25 billion in 2006. More indirectly, China's economic expansion and corresponding demand have increased the prices of many of the goods that LAC trades, and therefore LAC improved its terms of trade in part owing to China (at least until 2007). Finally, the increase in trade directly and indirectly caused by China has given LAC more reserves that can prove useful during an economic crisis such as the current one.

The China boom has not been without cost for LAC, however. Although the level of LAC exports to China has surged of late, exports to China as a share of total LAC exports have stayed the same for decades. What is more, six countries and ten commodities dominate all LAC trade with China, meaning that many LAC countries have not seen much of a change in exports at all as a result of China. Of more concern is that virtually all of LAC's exports to China are in the form of primary commodities. Commodities markets are notoriously volatile, and the long-term trend for commodities prices is negative. If China demand then contributes to an increase in the specialization of LAC production, LAC's terms of trade could deteriorate and affect the region's growth prospects for decades. Moreover, without the proper environmental policies in place, surges in commodities exports to China can leave a large environmental footprint. Many of these potential costs can be avoided if some of the potential benefits of China trade are set aside to mitigate those costs.

The costs of lost world market need to be juxtaposed alongside the benefits of increased exports to China. In chapter 3 we examine the extent to which LAC is competing with China in world and regional manufacturing markets. Based on measures of export similarity and initial market share, only a handful of countries compete with China (at present): Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Mexico. We calculate the extent to which manufactures exports in these and other LAC countries are “threatened”—meaning that China's growth in an export sector is much faster than a LAC competitor in that sector—by China's rise. Astonishingly, we find that 94 percent of LAC's manufactures are threatened by China, representing 40 percent of all LAC exports. LAC manufactures are still growing, but at a slower pace and in sectors where China is rapidly increasing its market share.

The jewel of manufactures trade, and trade-led growth in general, is high technology. Nations that diversify into high-technology exports grow faster and better. Some LAC nations, particularly Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico, made significant inroads in global high-tech markets during the high-tech boom of the 1990s. chapter 4 focuses on the extent to which China is outcompeting LAC high-technology manufacturing and services exports in world and regional markets. China's rise in this regard has been unprecedented. We find that China has gone from being one of the most insignificant high-technology exporters to the number-one high-technology manufacturer in the world. The only two LAC nations that have maintained some significance in international competitiveness are Brazil and Mexico. We find that 95 percent of all high-technology exports in LAC are under some threat from China. What is additionally striking about the Chinese case is that China's composition of high-technology exports has not only increased but also diversified during its surge. In other words, whereas China started its high-tech export surge by serving as a low-wage haven for low-skilled goods, it has climbed the technology ladder and now exports personal computers, cars, appliances, and other high-tech goods under Chinese name brands. Mexico, on the other hand, has gained competitiveness only in low-wage, low-skilled high-tech goods.

Because Mexico tops everyone's list of nations under direct threat from China, we devote two whole chapters to the Mexican case. chapter 5 empirically examines the extent to which China is outcompeting Mexico in Mexico's most important external market, the United States. By any measure and in every analysis, Mexico stands out as the most similar to China (in terms of export structure) and mostly likely to be affected by it in world markets. In chapter 5, then, we perform a Mexico-specific analysis and confirm that Mexico is already experiencing cutthroat competition with China that is starting to have a very negative effect. Ninety-nine percent of Mexico's manufactures exports, comprising 72 percent of all Mexican exports, are under threat from China. As we show in this chapter, many manufacturing firms have relocated from Mexico to China, and statistical analyses show that China is significantly affecting Mexican manufacturing in a negative manner.

Chapter 6 tries to shed some light on the causes of China's relative increase in competitiveness, going behind the statistical analyses of previous chapters and conducting a comparative analysis of trade and industrial reform in China and Mexico, the LAC country most affected by China. It is striking how two countries with very similar profiles of manufacturing exports that liberalized both their markets ended up on very different trajectories. Based on field research, statistical analysis, and an assessment of the peer-reviewed literature, we detail macroeconomic, trade, and industrial innovation policy in the two countries during the period of reform. What becomes clear is that China has actively managed the globalization process, and Mexico thought that markets alone could manage Mexico's economy.

In Chapter 7 we summarize our results and key findings and draw implications for research and policy. Rather than blaming China for LAC's poor performance, we encourage the LAC region to look inward for the source of its lack of competitivene...