![]()

ONE

Contexts and Causes

We [doctors] are employed in . . . a necessary calling that enforces to us the weakness and mortality of human nature. This earthly frame, a minute fabric, a center of wonders, is forever subject to Diseases and Death. The very air we breathe too often proves noxious, our food often is armed with poison, the very elements conspire the ruin of our constitutions, and Death forever lies lurking to deceive us.1

BENJAMIN RUSH, 1761

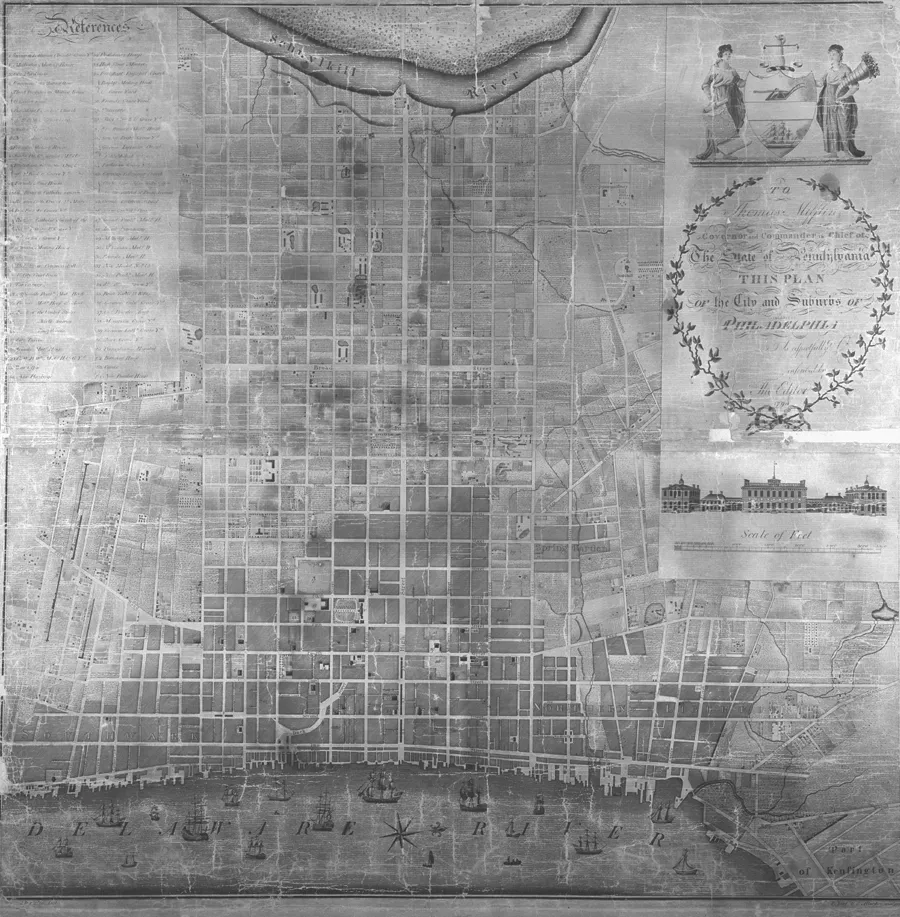

What caused yellow fever? The question was on most everyone’s mind in the United States’ capital in the winter of 1793, as legions of Philadelphians, some twenty thousand in all, trudged back into the city they had abandoned only months before. Those seeking answers would have found them, lots of them; indeed, more than they would have liked. People were talking and the newspapers were all abuzz with word of the disease. According to Mathew Carey, “almost all” Philadelphians believed that the disease came from abroad, probably along with the two thousand French-speaking refugees from Saint-Domingue who had arrived in the ports of Philadelphia earlier that summer, some of them allegedly infected with yellow fever.2 Others implicated the conditions of the city: the stinking cesspools, the decaying animal carcasses, rotten vegetables, and stagnant pools of water that bred pestilential miasma. A pseudonymous writer for John Fenno’s Gazette of the United States, masquerading as William Penn, the founder of Philadelphia writing from the “Elysian fields,” chided his contemporaries for straying from his plan for the city. “It was my intention in laying the plan of Philadelphia,” the ghost of Penn wrote, “to provide for the health as well as the beauty and conveniency of the place” (Figure 1.1). The author, evidently a localist, blamed city-dwellers for cutting down trees, narrowing the streets, and building where they should not. “Had you preserved my plan,” the imposter informed his readers, “you might have avoided the mischief which has now befallen you.”3

Figure 1.1. Plan of the city and suburbs of Philadelphia, 1794.

SOURCE: Historical Society of Pennsylvania Of 610 1794.

Those learned in science and medicine set out to solve the puzzle. Benjamin Rush opened the commentary. The forty-eight-year-old professor of the theory and practice of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania was one of the foremost physicians in the United States, and an established figure in the nation’s intellectual life. Born in Byberry, Pennsylvania, on Christmas Eve 1745, Rush studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh under the illustrious William Cullen. Once back in Philadelphia, Rush became the professor of chemistry at the College of Philadelphia, and he joined the American Philosophical Society. He later served in the Continental Congress and signed the Declaration of Independence. Rush labored hard to improve the medical and scientific reputation of Philadelphia, a city he rather hopefully deemed the “Edinburgh of America.”4 To that end, he helped form the College of Physicians of Philadelphia in 1789. A fierce Protestant, full of evangelical fervor, Rush also championed numerous causes—he campaigned for temperance, wrote essays against slavery, pushed for prison reform and women’s rights, and argued for municipal sanitary reform. But there was also a darker side to the good doctor, a domineering intellectual who did not suffer contrary opinions.5

No one would have been surprised when Rush’s localist manifesto, An Enquiry into the Origin of the Late Epidemic Fever in Philadelphia, began appearing at the city’s numerous bookshops in December. Yet for all his erudition, authority, and gravitas, Philadelphia was scene to a vibrant and disputatious public culture, and so Rush immediately encountered opposition. Late in 1793, William Currie published a pointed rebuttal of Rush’s first treatise. The son of an Episcopal clergyman, Currie like Rush was a native of Pennsylvania, and a member of both the American Philosophical Society and the College of Physicians. But Currie differed from Rush in a more pertinent respect—he lacked formal medical education. Though he attended some courses at the College of Philadelphia, he learned his trade chiefly through an apprenticeship with Dr. John Kearsley and as a surgeon for the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War.6 Currie’s humble origins, his hands-on training, and his proficiency in the manual skill of surgery contrasted with Rush’s impeccable education credentials and his more philosophical approach to medicine. The rivalry that emerged in the aftermath of the first outbreak lasted for the rest of the epidemic period.

And so, in the spring of 1794, when Rush published An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, a far lengthier effort, Currie immediately followed with his own full-length work, A Treatise on the Synochus Icteroides, or Yellow Fever. By that time, too, several others had joined the conversation. In their own treatises, Jean Devèze, an emigrant doctor from Saint-Domingue, and David de Isaac Cohen Nassy, a doctor and member of the American Philosophical Society, sided with the localists. On the other side, Dr. John Beale Bordley Jr., the scion of a wealthy Maryland family, and Isaac Cathrall, a doctor and surgeon, decided on importation. Even the bookseller, Carey, entered the fray with a short contagionist essay.

Epidemics in Baltimore in 1794 and 1795, and New York in 1795 and 1796, elicited similar responses.7 Yet, as the winter of 1796–97 settled over the Eastern Seaboard, localists and contagionists still vied for recognition as the purveyors of the authoritative explanation for the cause of yellow fever. The stalemate calls for examination of the investigators’ ideas about disease causation, and about nature and the proper means of investigating it. Captivated by science and its grounding in empirical evidence and inductive reasoning, the investigators sought the facts of yellow fever. But since the facts reflected the etiology of yellow fever, the facts only deepened the controversy. One group sought answers from more elusive sources. Weaned on Scottish philosophy and taught that God’s goodness suffused everything in creation, the localists insisted that the matter could be decided by common sense, a mental faculty that reveals as much about localist preconceptions of nature as the broader ideational forces hovering around natural inquiry in the late eighteenth century. After the first few years, the investigators remained bitterly opposed, but they had exposed the philosophical flaws that invested the problem of yellow fever with new significance and drove the debate forward.

In the late eighteenth century, Western-educated medical thinkers accepted localist and contagionist models of disease transmission. Both had ancient lineages, though contagionism most certainly predated its counterpart. Evidence from ethnographic fieldwork and early historical texts indicates that people predictably envision disease as an entity that can be caught from others. At the least, humans across time and space metaphorically construe even nontransmissible diseases as contagious and shun their victims as tainted. When disease struck Athens during the Peloponnesian War, citizens predictably concluded that it arrived from Ethiopia. In biblical texts, the fear of contagion translated into elaborate laws and procedures for isolating the sick and purifying infected areas.8

Contagion remained a vague concept until the seminal work of the Veronese humanist scholar Girolamo Fracastoro (1478–1553). In a groundbreaking work, De Contagione et Contagiosis Morbis et Eorum Curatione (1546), Fracastoro offered a comprehensive view of contagions as specific types of “imperceptible particles,” or seminaria. According to him, once seminaria implanted in a human body, the infected body produced identical seminaria, which could then be transmitted to others. The seminaria possessed unchanging natures and they could be reproduced infinitely, so long as they came into contact with bodies conducive to them. Fracastoro further specified that some particles spread only through direct contact between bodies, while others could survive for long periods of time without a host.9 Crucially, however, Fracastoro did not know what originally produced the seminaria, though he hypothesized that they might originate in the body or in the outside world as a result of unfavorable planetary alignments.

Borrowing from the tradition established by Fracastoro, the investigators imagined the material cause of yellow fever as a specific, though invisible, particle of matter. As Columbia Professor Richard Bayley wrote in 1796, “By contagion we understand something peculiar and specific, possessing properties essentially different from anything else.”10 The contagionist Cathrall identified three ways through which these “peculiar” and “specific” particles infected hitherto healthy individuals: first, through “immediate contact with the patient’s body”; second, through “the matter of contagion arising from the morbid body impregnating the atmosphere of the chamber, and being applied to susceptible constitutions”; and last, from “substances which had imbibed the matter of contagion” and had “the power of retaining and communicating it in an active state, such as woollens, furs, &c.”11 Cathrall likened the contagion of yellow fever to the contagion of the much better understood smallpox, a baneful disease in the eighteenth century. Long experience with smallpox had convinced everyone, even those who most strenuously argued for the local origins of yellow fever, that it operated through contagion.12

Unlike contagionism, localism derived from a specific place and time: fifth-century BC Greece and the works imputed to Hippocrates of Cos. Like contagionism, it rested on observations about the patterns of certain diseases. Hippocratic authors acknowledged the existence of a class of diseases, known as fevers, which were not manifestly contagious. Noticing that fevers came tied to local environmental conditions, they conjectured that they spread to humans via environmental corruptions, or miasmas (the Greek word for “impurity”), such as the exhalations from marshes. Undoubtedly the fevers to which they referred were forms of malaria (from the Italian for “bad air”), an endemic disease long present in Greece, which is caused by any of a number of protozoa, called plasmodia, and spread through the bites of female mosquitoes of the genus Anopheles.13 Since Anopheles mosquitoes prevail in specific environmental conditions, hot and wet areas, the fevers they transmitted appeared to have been caused by those conditions.

In North America localism appealed to the scores of doctors who confronted the deadly ravages of malarial “fevers.” Known to Americans as the “bilious,” “remitting,” “intermitting,” or “autumnal” fevers, the falciparum and vivax varieties of the malaria plasmodia, along with its insect vector, Anopheles quadrimaculatus, imposed a harsh reign over the Low Country of the American South. Malaria also struck farther north, in and around cities such as Philadelphia and New York, where it was known as the “autumnal” fever, for its tendency to strike during the hottest and rainiest time of year.14 Given its environmental specificity, however, everyone agreed that these “fevers” were caused by miasmas. In his health manual for inhabitants of the malarial Low Country, the doctor turned historian David Ramsay claimed that the seasonal fevers arose “from the separate or combined influence of heat, moisture, and marsh miasmata.” Even Currie, the most energetic advocate of the contagionism during the yellow fever years, acknowledged the local origins of Philadelphia’s “autumnal” fevers.15

The fever investigators believed that miasmas possessed physical properties. Countless particles of matter, miasmas emitted from decaying or putrid substances—such as rotting carcasses or the fetid matter in swamps and stagnant waters—and then either hovered in the air, like dust or pollen, or were themselves different types of air. Borrowing the language of Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier’s new chemistry, investigators described miasmas as the products of fermentation, the process by which the chemical bonds that held living bodies together dissolved, only to form new, sometimes deadly, combinations. Given their identification with the aeriform state, disease inquirers likened miasmas to odors (they often described them as “putrid” or “noxious” “effluvia” or “exhalations”), which they believed arose from the constitutive elements of the matter from which they came (thus, the characteristic smell of, say, wood came from small pieces of floating wood).16 One anonymous investigator rather fancifully tried to prove the local origins of Philadelphia’s fevers by claiming that he knew someone who could smell the putrefactive miasmas choking the city.17

Localism and contagionism offered early republicans compelling models for considering the origins of new and unfamiliar diseases such as yellow fever. Both held that small pieces of noxious material entered the fragile, temperamental human body, inducing states of disease. Moreover, both approaches convincingly and unambiguously explained the causes of certain diseases. Clearly, then, the fever investigators did not simply appeal to their favorite theory in order to explain yellow fever. They were still faced with an important question: Given the existence of two long-standing, widely accepted models of disease transmission and causation, how were they to determine which one applied to yellow fever?

Though they would come to disagree over a great many points, the investigators agreed that the problem of yellow fever demanded “facts.” The lexicographer Samuel Johnson defined a “fact” as “a thing done; an effect produced,” adding that it could also be described as “reality; not supposition; not speculation.”18 Conceived as distinct pieces of knowledge, or as isolated observations or measurements of nature, facts provided the building blocks of deeper understandings. Crucially, facts enjoyed a “rugged independence of any theory”—they would still be facts even if they did not agree with favorite theories, or if there were no theories to explain them—which suited the dominant epistemological orientations of early American knowledge producers.19 Since anyone could produce facts, and most could evaluate their meanings, facts negated social distinctions and educational levels. Facts freed natural inquiry from the clutches of entrenched authorities, systematizers, and learned, though frequently misguided, theorists. In a society that was deeply suspicious of authority and disdainful of elitism, the facts linked inquirers to a transparent, egalitarian method of knowledge production, in which truth c...