![]()

PART I

Reconstructing a Woman’s Life

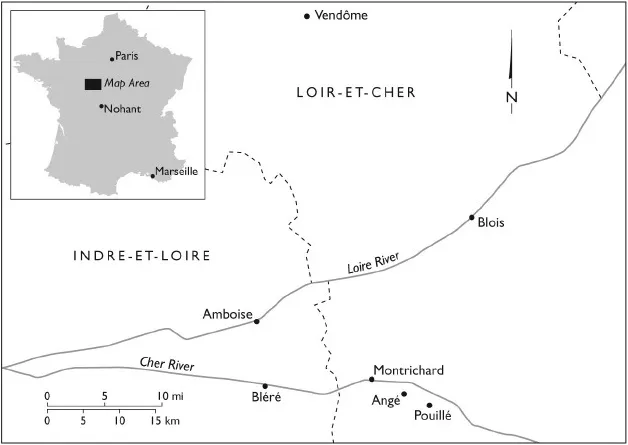

Montrichard, where Eugénie Luce was born, and surrounding towns in the Cher River valley.

![]()

1

GROWING UP IN PROVINCIAL FRANCE (1804–1832)

Véronique Eugénie Berlau1 was born in Montrichard in the Loir-et-Cher on 20 Floréal Year XII (10 May 1804), eight short days before Napoleon Bonaparte’s decision to crown himself emperor of France and a few weeks after the French civil code durably inscribed women’s inferiority into law. The same year also saw the birth of the famous woman novelist George Sand. Like Sand, Eugénie defied many of the conventions defining appropriate womanly behavior. And like Sand, she acquired a measure of notoriety during the heady years of the July Monarchy (1830–1848). Unlike Sand, this notoriety is not visible in the pages of history because Eugénie left no written oeuvre and her battles for recognition took place in Algeria, not in metropolitan France. Although both women lie buried in villages not far distant in the rolling landscapes of central France, no tourists visit Montrichard in the Loir-et-Cher in search of Eugénie Luce, in contrast to Nohant-Vic in Indre, whose tourist industry thrives thanks to the reputation of George Sand.

The juxtaposition of the two women is not just a literary device. Madame Luce wrote to Sand in the 1860s and liked to associate her name with her illustrious contemporary. Perhaps she imagined parallels in their life stories; perhaps she had dreams of achieving similar notoriety. This we will never know. Luce left no written traces of her more introspective musings, nor did she devote her declining years to writing a memoir. As a result, very little remains to reconstitute her childhood and youth, her emotions upon marrying, her feelings about motherhood, or the heartbreak associated with losing infant children. Fortunately, she left some indications about her childhood and youth, but not all of them are accurate. What follows, then, confronts her own romantic rendering of her past with the available archival information. Neither version does justice to the complicated business of disentangling the role of individual decision from the web of social and economic constraints, but combined they do shed some light on the circumstances that would later lead this obscure provincial schoolteacher to flee France for Algeria, abandoning her husband and five-year-old daughter. We begin with the only available description of Madame Luce’s youth and then turn to the archives, which reveal a somewhat different story.

A ROMANTIC FAMILY STORY

Sometime during the winter of 1857, the British feminist Bessie Rayner Parkes encountered Madame Luce through the intermediary of her close friend Barbara Bodichon. In letters to England to sister feminist Mary Merryweather, Parkes mentioned Madame Luce several times and offers the first relatively lengthy description of her new acquaintance:

Yesterday I spent part of the afternoon with Madame Luce who opened out and told me much of her private history. . . . She was one of a large family of 13 in Touraine, her maiden name was Eugénie Berlau. They were poor and at 16 she had a small school. At 21 she was married by her relations to a M. Allix, a man who had been educated in a seminary and had even sworn the Priesthood but threw it off before taking definitive vows and commenced as professor. This individual ill led her in various ways, beat and pinched her. She did not explain what his misdemeanors were except that that he took all her earnings from her school, which she still continued and she never had any of them for herself. Her father, M. Berlau, interfered several times, but there was no money to obtain a separation and she dreaded being in the newspapers. At length as a family in the neighborhood were going to Algiers, which was then hardly a conquered [territory] and certainly not a settled district [she left;] was not that a plucky thing to do? She left her little girl with her own family; coming to Algiers, she struggled on. . . . Her husband wrote over to the Algerine authorities to reclaim her, and they told her they must send her back. She declared that if they did she would try and throw herself off the deck of the vessel into the Mediterranean or if she could not do that would fly to Switzerland instantly on her arrival to seek the protection which French law would not afford. In which seeing it was a bad case and that she was getting her living honestly, she believes they wrote back to say there was no such person there. Was not that French?

This presentation is followed then by a description of Madame Luce’s early intellectual influences:

Then she told me how much she had been influenced in her childhood and youth by a certain old woman who lived in Touraine and was a market gardener. How this old woman had a wonderful head, and how one of her sons was head of the Collège at Blois, but how she would never accept anything from him but preferred sending her vegetables to market on a donkey. How this old woman had somehow been educated at Chenonceau [under?] the eye of Madame Dupin, who was daughter to Louis the 15th and grandmother to George Sand. There is a complication for you. George Sands maiden name was Dupin, but Mad Luce declares that her grandmother was an illegitimate daughter of the Kings and lived at the royal chateau of Chenonceau where she was visited by Voltaire and Jean Jacques! See Madame Luce and my beloved George Sand both indirectly nourished by the same stream of thought, and the old connexions with the Capets, son of St Louis. The world is not very big and the people in it are very few. You cannot think how I delight in a bit of pedigree and a romantic family story.2

Whether Madame Luce really believed this fanciful retelling of George Sand’s ancestry—Sand’s grandmother Marie-Aurore Dupin was the illegitimate daughter of Maurice de Saxe, not the king of France—she clearly perceived that establishing a connection between her own modest origins and that of George Sand added an appropriate degree of “pedigree” and romance that would appeal to her British audience.

In this description of early poverty, an arranged marriage, and spousal mistreatment, the heroine resisted the forces of oppression, and Parkes was sensitive in her retelling to Madame Luce’s early commitment to education and bold gestures. Parkes and her feminist friends defended women’s right to work and achieve financial independence. Not only did Allix abuse his wife, he also deprived her of her earnings. Madame Luce provided a story, which deliberately played on feminist and romantic chords, particularly in her description of the old woman market gardener.

Four years later Parkes offered a far more detailed presentation of “Madame Luce, of Algiers” in three long articles of the feminist English Woman’s Journal. Although Madame Luce’s activities in Algiers formed the heart of this chronicle, her British friend was clearly intrigued by her upbringing, to which she devoted five pages. Writing for a British audience, Parkes wanted to give her readership a sense of the texture of Luce’s family life as well as of the nature of women’s lives in the French provinces in order that they “understand the influences which surrounded this remarkable woman in her younger years.” 3 And while the articles unquestionably create a serious portrait of a woman worthy, the tone is leavened with touches of humor that must have come from the storyteller herself. Madame Luce collaborated actively in this project, providing a great deal of social realism that responded to Parkes’s concern to translate French realities for a foreign audience.

Early Life and Labors

This is how Parkes begins the story: “A short account of the life and labors of Madame Luce, of Algiers, appeared four years ago in a Scotch journal. Having lately had access to the numerous private and official documents required by any writer seeking to do justice to one of the most remarkable of living French women, I offer to our readers a detailed account of her efforts in the cause of education and civilization, hoping thus to add one more portrait to the gallery of our contemporaries who have deserved the gratitude of their kind.”4 Parkes then (inaccurately) places Eugénie’s birth on the sixth of June 1804 in the Hôtel de Ville of Montréchat, “a small town in Touraine containing a population of 2400 souls. Her father, an architect and engineer by profession, was at that time Secrétaire de la mairie at Montréchat.” After noting the birth “on the Monday of the great Feast of Pentecost,”5 the journalist moves back in time to describe the “mysterious” origins of the Berlau family. Eugénie’s grandfather was an orphan, raised by a prior, who upon discovering a mathematical equation on the ground decided this was a sign from Providence to become a professor of mathematics. Eugénie was the twelfth child of her parents and grew up mainly in the countryside in an “old château in the environs of Montréchat.” Despite this aristocratic setting, however, the Berlau family was not wealthy, since her father’s salary as an architect and engineer was small and his domestic circle large: “neither his profession nor his land appear to have raised his income to 500 francs, or £200 a year.” Parkes goes on to reflect, “How French households get on at all, and contrive to bring up their children, to settle their sons, and to marry their daughters, is a subject of constant astonishment to English people well acquainted with French interests.”

Parkes describes Eugénie as a “dreamy, studious child,” who acquired an education botanizing in the countryside around the castle, enjoying a freedom of action far different, Parkes explains, from that of her Parisian sisters: “mixing among the poorer neighbors, cognizant of their family histories, and involved in their experience.” Raised in a “very natural way,” Eugénie read indiscriminately in her father’s library, mingled with country people, and sought to “inoculate the shepherds on the estate with a love for the beauties of literature; for which effort they probably expressed more gratitude than appreciation.” Notwithstanding the absence of stern parental oversight, however, Parkes presents Eugénie as “extremely sage” (well-behaved) and pious; after her first communion at age eleven, she was so gifted at the catechism that the curé asked her to teach her fellow students.

This intellectually talented girl grew into a “very tall and strong” young woman, showing evidence of the “personal vigor and beauty” that her British friends appreciated more than half a century later, despite “manifold trials and labor.” But Eugénie is more than just a do-gooder in the feminist retelling. Parkes emphasizes as well that she was a young lady with a mind and political opinions, thanks to the influence of her father, who had been a devoted royalist and had transmitted his hostility toward Napoleon Bonaparte to his daughter. On two occasions, she showed her commitment to the royalist cause by tearing up a Bonapartist banner discovered on the property of a married sister and then out-singing a young Bonapartist boy in a musical tournament in 1815: “Song after song proceeded for some time without any flagging, but the moment came when, alas! Master A—’s memory was completely exhausted, whereas Eugénie, to whom her papa brought sheets of royalist rhymes whenever he went to town, continued crowing triumphantly like a little cock, to master A—’s infinite disgust and mortification.” When the guests tried to have them kiss and make up, the boy refused to honor “a young lady with such strong political principles and audacious lungs . . . and dealt her a hearty cuff, which it is whispered that Eugénie returned with interest.”

Familial tragedy also marked Eugénie’s early life when her older brother died at age twenty. Although only thirteen at the time, she sought to alleviate her parent’s grief by persuading them to move back into town: “As a further means of creating a little more movement in the house, she opened a small school, of which the pupils were as old as herself, but at thirteen she was so tall and womanly that no one would have guessed her age.” In these early years of the Bourbon Restoration (1815–1830), schools opened and closed without much control, but such an enterprise was nonetheless unusual. For several years Eugénie taught students, inspiring the local education inspector to encourage her, upon reaching eighteen, to pass a school teaching certificate.6 These were created for women in 1819, so if she had listened to the inspector, she would have been among the first female rural schoolteachers to receive accreditation.

Love and Discord

Eugénie’s youthful years were filled with more than just study, work, and concern over her parents, according to Parkes’s retelling. She also fell in love with the son of a judge. This young man was not her parent’s choice of a suitor, but they did not force her to marry the “young gentleman from Holland” they had chosen for her. Alas, her sweetheart died of consumption when she was still younger than twenty, and so “depressed and disheartened,” she accepted the marriage arrangement her parents had made for her with M. Allix. She presented this decision as a response to her parents’ “extreme anxiety to see her settled.” She did not want to be a burden to them.

Eugénie’s loquaciousness about her childhood faded into innuendo with respect to her married life: “Little is known, and nothing need be said, about this marriage, but that it was a very unhappy and unsuitable tie.” Still, she did tell her British friends that her future husband had been raised for the priesthood but renounced his vows. No mention of the mistreatment she recounted to Parkes makes its way into the English Woman’s Journal’s version of her history; instead, readers are told:

Why he married, and why once married he did not make his young wife happy, is one of those sad mysteries which are best left in the shadowed privacy of domestic life. That Madame Allix three times returned to her father’s house, and at last, with her father’s consent fled to Algiers, then recently acquired by the French is enough to say; and so great was her distress, and so moving her representations, that on M. Allix sending to inquire for the fugitive, the Algerine authorities actually sent back word that no such woman had been heard of in the colony!

Parkes mentions the existence of a daughter, left in France with Eugénie’s mother, but dwells lightly on domestic discord before plunging into the description of Madame Allix’s early years in Algeria.

This presentation of Eugénie’s early life highlights aspects of her character that clearly appealed: “a certain shrewd, practical simplicity of character”—so different from British representations of the frivolous French society woman—her strong will, her ability to rise above misfortune, and her determination to do something with her pedagogical talents. The story also contains a number of inaccuracies, such as her date of birth, the name of her native town, and the number of her siblings. The first two errors were probably inadvertent mistakes on the part of her British friends, but the issue of family size is more puzzling. Parkes carefully situates Eugénie’s birth within the Christian calendar, born on the “great feast of Pentecost,” celebrated as Whitsun in Great Britain, and then presents her as the twelfth child of her parents. This precision as to the number of children must have come from Eugénie herself, but why did she invent such a large family? Was this simply a penchant for exaggeration? Whatever the answers to such questions, the presentation bears all the marks of a good storyteller and does a nice job disrupting not just British representations of French womanhood, but also historical descriptions of women’s lives in the early years of the nineteenth century. We have very few portraits of lower-middle-class girls acting independently, expressing political opinions, and teaching. The archival version confirms the socioeconomic context Parkes described but offers little op...