![]()

1

BAIJIE’S BACKGROUND

Religion and Representation in the Nanzhao and Dali Kingdoms

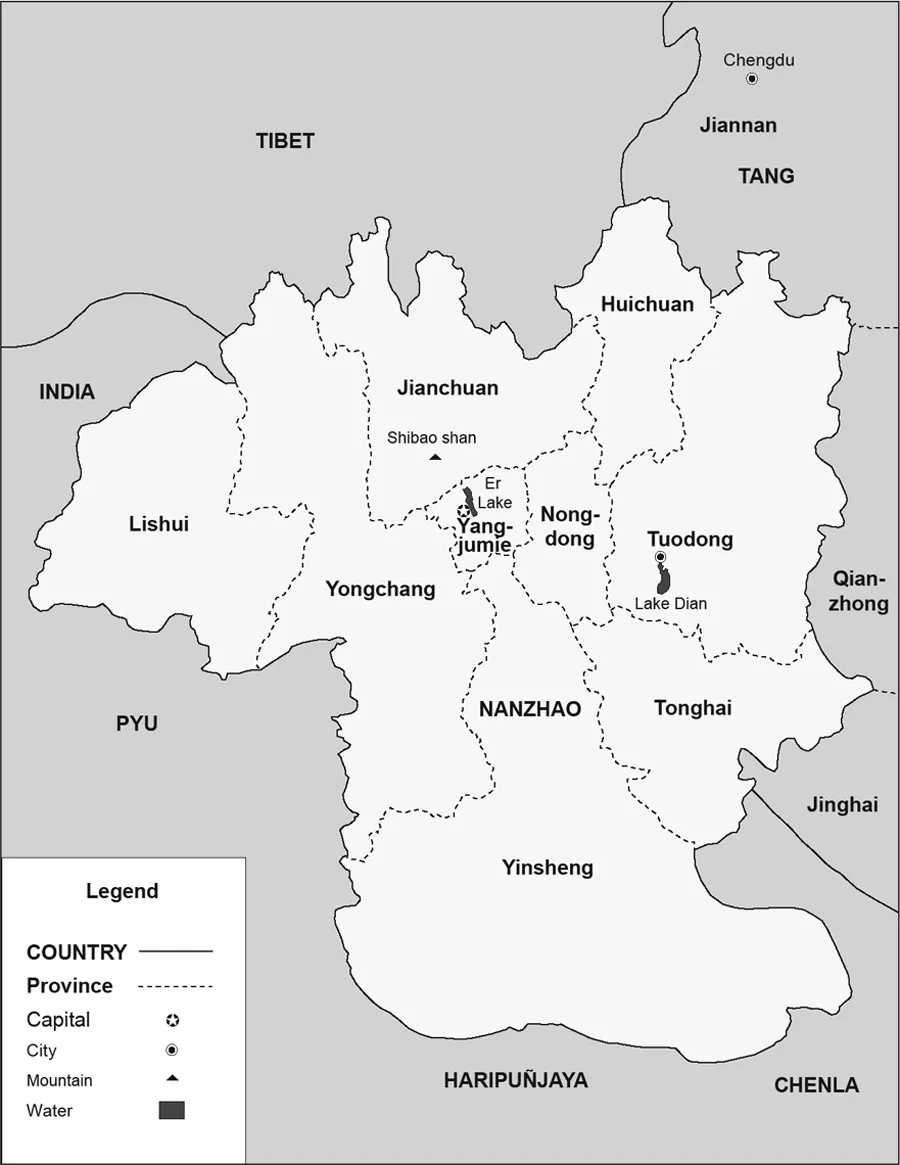

BAIJIE’S STORY begins in the Dali kingdom, an independent regime centered in the Dali plain that was roughly contemporaneous with the Song dynasty (960–1279). The preceding Nanzhao kingdom (649–903) laid the groundwork for Dali developments and played a central role in the region’s later formulation of ethnic identity. The Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms were the longest lasting of a series of independent regimes that ruled the area of modern-day Yunnan Province, along with parts of modern-day Sichuan, Guizhou, Vietnam, Laos, and Burma, from their capital in the city of Yangjumie, now known as Dali. They were surrounded by the kingdoms of India, Tibet, Southeast Asia, and the Chinese Tang (618–907) and Song dynasties. Understanding Baijie’s first form requires starting with Nanzhao and Dali culture, in order to locate Baijie within a broader context.

Dali’s position as a hub in cross-cultural networks means that studies of the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms, including their Buddhist traditions, have focused on which neighboring country exerted the most influence on the region. Scholars generally agree that Buddhism entered Dali along multiple routes, but differ on the relative importance of these channels. Among art historians, for example, Helen Chapin and Angela Howard identify Chinese, Indian, Himalayan, and Yunnanese styles in Nanzhao and Dali kingdom art, while Li Lin-ts’an and Lee Yü-min reject Himalayan influence.1 Buddhist texts from these periods are almost exclusively written in Sinitic script, which means that scholars who focus on texts tend to emphasize the region’s ties with Tang-Song China. Hou Chong, the leading scholar of Dali Buddhism, attributes the region’s religious culture solely to Chinese forces.2 This chapter reconsiders claims about the nature of Nanzhao and Dali Buddhism by examining visual and textual materials together, shifting focus from influence to agency and reevaluating the salience of “ethnicity” for understanding Dali’s population in this period.

Rather than focus on which neighboring country exerted the most influence on Nanzhao and Dali religion, I focus on Nanzhao and Dali agency in examining not only where the different elements of Nanzhao and Dali Buddhism came from, but why the ruling class adopted certain elements over others and represented their Buddhist tradition as they did. “Representation” underscores the exteriority of the identifications that appear in the sources rather than imputing an interior, psychological basis to them, and it does not assume that the sources of Dali Buddhism determine its meanings. Juxtaposing the networks by which Buddhist materials entered Dali with the representations of those networks in Nanzhao and Dali Buddhism illuminates how political and religious elites exercised agency in shaping court Buddhism.

In addition to emphasizing the role of agency in the development of Nanzhao and Dali Buddhism, I rely only on contemporaneous sources from or about the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms in order to avoid anachronistic interpretations of the region’s history. Quantitative limitations on sources from Nanzhao and Dali have led some scholars to rely on Ming (1368–1644) and Qing records about the transmission of Buddhism to Dali, despite the complete absence of Nanzhao or Dali records corroborating these accounts. The ethnonym “Bai” (or “Bo”), which only becomes widespread in the Ming and Qing and is used today as a “nationality” (minzu) designation, is read back into Nanzhao and Dali history.3 Hou Chong’s recent work, which reveals the later construction of Dali’s legendary history, has provided a much-needed corrective to this problem, but more remains to be done.4

The quantitative limitations of extant sources complement their qualitative limitations: almost all extant materials about the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms come from the Tang and Song dynasties, and almost all extant materials from the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms are written in Sinitic script and contain few details about foreign relations with countries other than China.5 This raises the question of whether surviving sources represent Nanzhao and Dali history or if many non-Sinitic documents disappeared with the increasing Chinese influence of later centuries.

The sources’ limitations foreground China-Dali relations, but this does not entail adopting the perspective of Chinese discourse, which places the Dali region on China’s periphery and labels its inhabitants “barbarians.” Nanzhao and Dali paid tribute to the Tang and Song courts and in doing so adopted a subservient role, but this does not mean Nanzhao and Dali rulers blindly accepted the terms of Chinese discourse. Nanzhao and Dali rulers’ self-representations show how they actively engaged with Chinese discourse and positioned themselves geopolitically and historically. Even without much information concerning the Nanzhao and Dali kingdoms’ interactions with their other neighbors, this reveals how such interactions were depicted for an audience that could read Sinitic script.

Looking at Nanzhao and Dali elites’ engagement with Chinese discourse also prompts reconsideration of ethnicity under these kingdoms. Ethnicity has been central to academic discussions of Nanzhao and Dali history, but the category of ethnicity does not emerge in representations of collective identities from these kingdoms. Focusing on Nanzhao and Dali rulers’ self-representation provides a new perspective that does not privilege Tang and Song writings, which record ethnonyms rooted in the Chinese-barbarian binary; the uncritical use of these sources in secondary scholarship reifies the Chinese discourse that spawned them. Though Nanzhao and Dali elite self-representation cannot be called ethnic, it does draw on gendered discourses that intersect with Chinese notions of barbarism and civilization. Tang and Song writings highlight how gender practices in Nanzhao and Dali diverge from those of Chinese culture, while Nanzhao and Dali sources allow for divergence in masculinity but not in femininity.

The Dali Region in History

CHINESE DYNASTIES IN YUNNAN: HAN THROUGH SUI

Before the seventh century the Dali region does not feature prominently in Chinese records. Instead, Chinese records focus on areas to the east and west of Dali where the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) established the Yizhou and Yongchang Commanderies as part of their imperial expansion.6 Han interest in the area stemmed from its potential for developing trade routes with India and its natural resources of salt and precious metals.7 The Dali region, called Yeyu in this period, first fell within Yizhou Commandery, but became part of Yongchang Commandery after the latter’s founding. The area controlled by these two commanderies had a diverse population before the arrival of Han representatives, though Han records only provide substantial information about the more powerful among them. Within Yizhou was the Dian kingdom (ca. fourth century–109 BCE), which according to the Han shu (Han history) was ruled by the descendants of the third-century BCE Chu general Zhuang Qiao.8 The Dian ruler reportedly offered his submission to the Han, for which he was granted the seal of office and invested as the Dian king.9 Even though the Dian rulers’ purported ancestral homeland was closer to the Chinese heartland than Yunnan, their kingdom still fell into the category of “barbarian.”10 Yongchang Commandery was home to the “Ailao barbarians” (Ailao yi), who reportedly submitted to Han rule but rebelled several times shortly thereafter. The Ailao adopted neither Chinese appearance nor ancestral claims: the Hou Han shu (History of the Latter Han) describes the Ailao as having pierced noses, stretched ears, and tattoos, and it recounts the origin myth of the Ailao that traces their ancestry to the coupling of a woman and a dragon at a pond below Ailao Mountain.11 The differences between the Dian rulers and Ailao—at least as described by the Han—show that the population of Yunnan had differing degrees of exposure to and acceptance of Chinese culture before the establishment of Yizhou and Yongchang Commanderies.

The Han presence in Yunnan familiarized some of the native population with Chinese culture but did not impose Chinese culture upon them. Though Han expansion into the Southwest brought a wave of settlers from the empire’s interior, the Han lacked the resources to enforce strong central rule. Their presence in Yunnan relied on the cooperation of native authorities, with whom Han officials tried to cultivate mutually beneficial relationships. After the fall of the Han, subsequent Chinese dynasties maintained administrative offices in Yunnan.12 Until the Tang, these offices possessed virtually no real power, but they served as a constant reminder of the Chinese tradition introduced to the region by the Han.

NANZHAO FOREIGN RELATIONS

With Tibet’s rise in the seventh century, the Dali area became militarily important for the Tang. When Tang officials reached the Er Lake plain in the 650s, the region was divided into six small kingdoms called zhao; the strongest was the southernmost kingdom of Mengshe, also called Nanzhao, or “Southern Kingdom,” and ruled by the Meng clan.13 The term zhao, which means “king” and “kingdom,” resembles a Thai word with the same meaning.14 This resemblance has been cited by scholars as evidence that Nanzhao was a Thai kingdom, a theory that has now been debunked based on analyses of other Nanzhao vocabulary and Nanzhao culture.15

Tang-Nanzhao (and Zhou-Nanzhao) relations began by the late seventh century, when the Nanzhao rulers Xinuluo (r. 649–674) and Luosheng (r. 674–713) sent tribute missions to the courts of Gaozong (r. 649–683) and the female emperor Wu (r. 690–705).16 This was an important gesture owing to the Tang’s weakening position in Yunnan, where many groups north of Dali had given their allegiance to Tibet. To reward the Nanzhao rulers’ loyalty, Tang did not attempt to limit their expansion: when Piluoge (r. 728–748) wanted to conquer the other five zhao in the 730s, he received approval from the Jiannan military commissioner Wang Yu (with the help of a generous bribe) and was granted the title “Yunnan King” (Yunnan wang).17 The Nanzhao rulers shifted their base from the Mt. Wei area to the Dali plain and established Yangjumie as their capital.

MAP 1.1. Nanzhao kingdom (649–903)

The Tang-Nanzhao friendship was short-lived. With Nanzhao expansion, the Tang began to fear that by supporting this powerful ally in the Southwest they had created a dangerous rival. Tensions came to a head...