![]()

PART I

READERS AND WRITERS

![]()

CHAPTER 1

CHÈRES LECTRICES

Cinderella Powder, Poet Queens and the Woman Reader

In the back pages of Femina’s first issues, full-page advertisements described the wonders of the beauty-enhancing Cinderella powder and soap (Fig. 1.1).1 Drawing on the fairy tale heroine, one advertisement claimed that Cinderella’s dramatic transformation was not unfamiliar to many women: “All creatures of beauty and seduction have a double life.” Furthermore, the ad insisted that Cinderella was very much alive in Belle Epoque France—as witnessed by several recent performances and publications—and was poised to pass on her secrets to “all women, her sisters, so that they could be, like her, sure to please.”2

This advertisement performs, I would suggest, the work of Femina and La Vie Heureuse themselves: they both served as a kind of Cinderella powder, introducing women to new worlds that fascinated because of their exclusiveness and inaccessibility, while at the same time allowing women to identify with the realm of the elite and to view their own existences as refracted through its beautifying, edifying lens. Cinderella powder promised to transport women to a realm of fantasy in the context of their daily lives. At the same time, as the advertisement suggested, Cinderella was no longer an exclusive sort of figure. All readers were capable of—and entitled to—her upscale existence; it was simply a matter of learning her secrets. Cinderella thus symbolized at once an aristocratic elegance inscribed in a longstanding and revered courtly tradition, and the democratization of that elegance, available now to all, regardless of birth.

Both La Vie Heureuse and Femina were in this sense perfect vehicles for the democratization of luxury that Emile Zola had identified decades before in his novel about the department store, whose drama grew directly out of women’s newly available purchasing power.3 The magazines were filled with articles on real-life royals, alongside advertisements for fashion and furs; study these women’s lavish interiors and then run to the furniture shop advertised a few pages later and buy that same lamp. This was, at least, the initial way in which those whose privileged destinies were meant only to cast a little warm light on a mundane existence very quickly became models to emulate. Yet while the Cinderella advertisement focused on beauty and seduction, both magazines were soon coupling their affirmation of conventional feminine norms with an insistence on women’s capacity for other kinds of stunning transformations, as they featured them in an array of compelling new roles. Indeed, both publications energetically invited readers to not just admire these new models of female achievement but to imitate them; the democratization of luxury so clearly celebrated in these magazines at the outset became, over time, tightly linked to what I am calling a democratization of female intellect, as the magazines insistently encouraged their readers to become thinkers and writers themselves.4 This chapter explores the process through which Femina and La Vie Heureuse constructed a new kind of reflective woman reader, who was seen not just as a consumer of goods, but of culture and literature. Part of Belle Epoque literary feminism’s most important work—and its appeal—was to make its devoted lectrices into veritable collaboratrices, an outcome that, by both magazines’ own admission, was both welcome and unexpected.

Figure 1.1 Advertisement for Cinderella powder and soap, Femina (March 15, 1902).

Becoming a Princess

The first issue of La Vie Heureuse explicitly formulated a proposed relationship between its readers and the select, elite women who would be featured in its pages. In the mission statement included in their inaugural issue, the editors wrote:

There are female destinies so brilliant that the world seems to look at them with admiration. Their luminous reputations, their large estates and their radiant youth make these marvelous Women dazzle. But isn’t it good for other hardworking women to occasionally catch a glimpse, as if in a dream, of the lives of queens and princesses, of Women who are the most refined expression of the elite of all species? In this heaven filled with fortune and splendor shouldn’t the less fortunate get to see the care, worries and obligations that compensate for the privileges with which these ones had the fortune to be born?5

This justification for readers’ anticipated fascination with famous women conforms to certain traditional theories of fame through which celebrities were viewed as models of an ideal existence that offered a respite from the banality of the fan’s own necessarily more mundane reality.6 Inscribed explicitly in an aristocratic model, the elite women to be featured in the magazine were deemed worthy of attention simply because of their birth. The ideal of happiness embodied by these special “Women” would appear in La Vie Heureuse, “in its true state,” promised the editors, as they offered readers comfort from—while inevitably reminding them of—their lesser lot. Those lucky enough to catch a glimpse of these bright lights could thus “return more satisfied to the modest calm of their own condition.”

And yet, even with this insistence on traditional class structures, the editors clearly suggested a shift towards a more democratic paradigm: while these exceptional women were born into their superior role, realizing their grace required work. By opening a window onto the “care, worries and obligations” required of them, the magazine also ensured a lessening of the gulf between humble readers and destinées brillantes—between “women” and “Women,” as it were. In appealing to an aristocratic model, La Vie Heureuse addressed a conservative readership eager to hinge modern femininity to familiar French ideals. Yet the fact of putting these women, their homes, children and intimate thoughts on display through a captivating layout of images and text was actually a key step in making these famous women more accessible, collapsing the distance between admired and admirer.

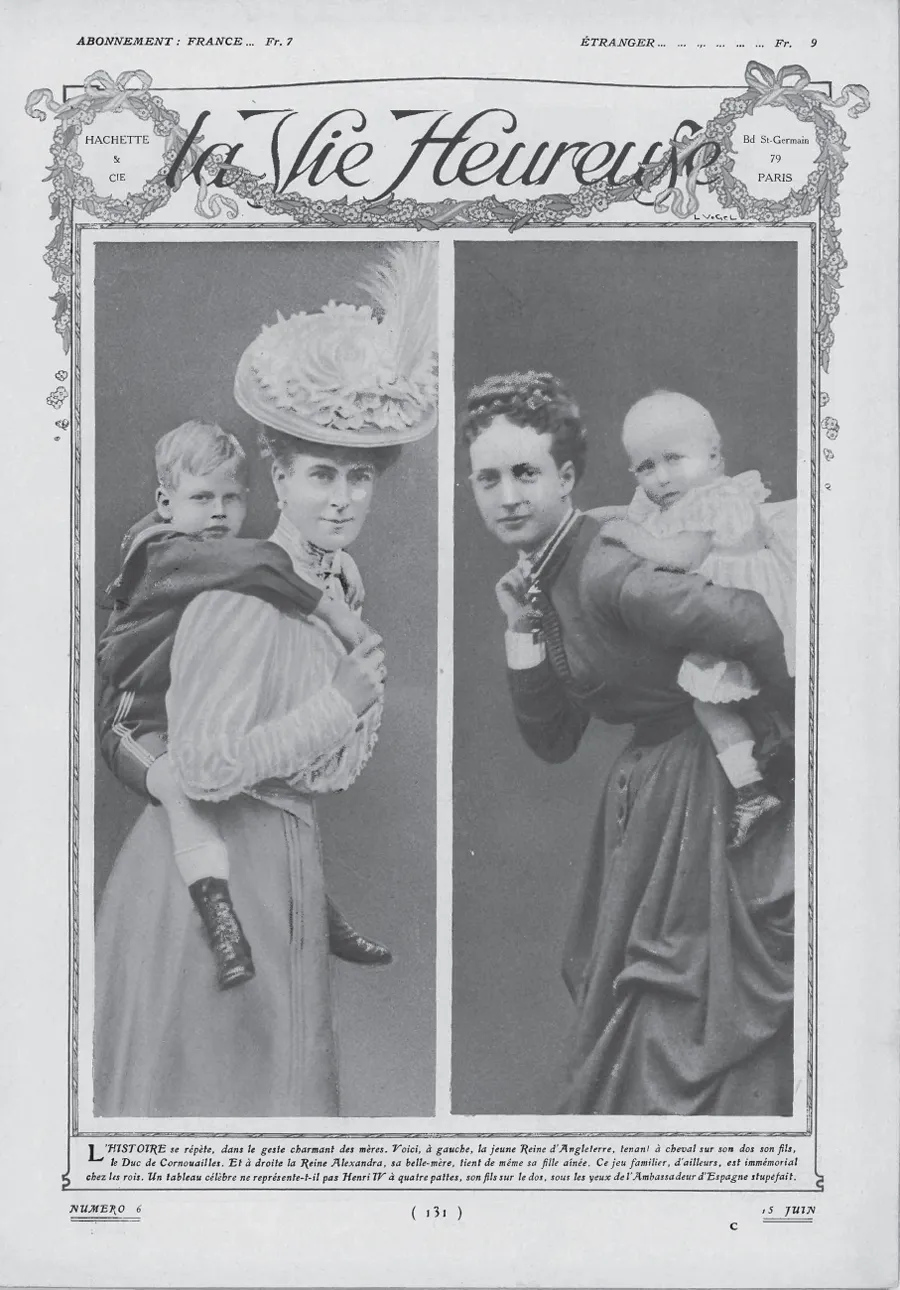

In fact, the women of La Vie Heureuse were compelling at once because of their exceptionalness, and because of the ordinariness and familiarity of their domestic preoccupations. The magazine’s repeated depiction of female royals tending to their children provides a perfect example of this dynamic. The June 15, 1910 frontispiece featured a startling photograph of the queen of England giving her young son a piggyback ride (Fig. 1.2). Similarly, a September 1907 story, “Young Royal Mothers,” showed several queens and princesses holding their children. On the one hand, the text of this particular story details the somewhat exotic rituals that follow a royal birth, like the firing of one hundred canons. On the other hand, what the accompanying iconography demonstrates in a series of images of mothers cradling children, and what the article ultimately concludes, is that royal motherhood is no different from that of the rest of society: “Outside of political realms, queens are nothing more than young women watching tenderly over their precious, frail offspring [. . .] under their sparkling crowns, they laugh with their babies like the most modest of their subjects.” La Vie Heureuse’s success thus offers perfect evidence for Lenard Berlanstein’s and Vanessa Schwartz’s claims that celebrity “united rather than divided the upper classes and the masses” by the late nineteenth century in France, and that spectatorship—in this case, through an endless array of photographs—“had the power to convert potentially antagonistic classes into a culturally unified crowd.”7 Readers of this story, mothers everywhere, were asked to see the royals they admired as fundamentally no different from themselves.

Rather than “return more satisfied to the modest calm of their own condition,” then, everything about La Vie Heureuse seemed to encourage women to see a better version of themselves in the ever-expanding smorgasbord of models of modern femininity. Bit by bit, it seems, the stars whose privileged destinies were meant only to cast a little warm light on a mundane existence easily became paragons of achievement, if not models to emulate. The very women celebrated within the pages of both magazines immediately invited this slippage. La Vie Heureuse seemed at first to suggest that the women it would feature had gained their distinction by birth. The first issue contained an article, just a few pages after the mission statement cited above, on the acclaimed poet Countess Anna de Noailles, seemingly confirming this fact. And yet, her presence in the magazine was assured as much by her literary prowess as by her aristocratic lineage, which turned out to be the main focus of the article, in which her poetry was quoted and extensively commented upon. In fact, within the first months of the magazine’s existence, the distinction between women born into glory and those who had earned it by talent quickly dissolved: distinguished women writers and artists were regularly depicted as celebrities in the magazine, alongside queens and princesses. In feature after feature, these women’s children were pictured, their home decor and sartorial choices examined and glorified. They had become veritable celebrities, a status defined in part by the blurring of the line between their public accomplishments and private lives.8

Figure 1.2 The queen of England (left) giving a piggyback ride to her son, the duke of Cornwall; her mother-in-law, Queen Alexandra (right), holding her oldest daughter. Frontispiece to La Vie Heureuse (June 15, 1910).

“Chères lectrices”

Like La Vie Heureuse’s, Femina’s aristocratic valences were mitigated by its repeated efforts to draw the reader closer, collapsing social boundaries between reader and editor, between the aristocratic world that it glorified and the lives of the readers it sought to enhance. This is apparent from its very first issue of February 1901, even as it featured the Empress of Russia on its cover, Queen Wilhelmine in its first article, replete with images of her in royal garb and pictures of her estate, and lavish photographs of Prince Roland Bonaparte’s home (Fig. 1.3). To be a woman was, Femina explicitly argued, in itself a very special privilege, a kind of nobility really, and that is why the magazine would devote itself to offering “an exact idea of everything that takes place in her charming kingdom.”9

Femina cultivated its readers as a community, referring to them consistently and throughout each issue directly as “chères lectrices” (dear readers, in the feminine), if not “charmantes lectrices” (charming readers). The directness of this second person address encouraged readers to see themselves as fully part of, indeed implicated in, a conversation, rather than simply observers. It transformed the editorial voice into the semblance of an actual person on the other end. The repetition of the refrain also suggested a single person where there were many, bridging the gulf between reader and writer(s). In the regular column she began in 1908, writer Lucie Delarue-Mardrus encouraged readers to think of her as an “attentive and trustworthy friend,” and that was indeed the overall persona of Femina’s editorial voice. In addition, the repeated invocation of the magazine’s plurality of female readers served as a reminder to each individual that she was not alone, but rather part of a shared community of women that was separate, distinct and special.10 In her history of mass culture in fin-de-siècle France, Vanessa Schwartz argues that at the end of the nineteenth century “the apprehension of urban experience and modern life through visual re-presentation was a means of forming a new kind of crowd” and that these “re-presentations” had the effect of effacing class and gender “in their conceit that diverse consumers should, could and would have similar access to them.”11 The women’s press offered a similar experience in its effacement of class lines, while maintaining a deliberately gendered point of view that only further contributed to the illusion of exclusiveness, in the special kingdom of women.

Figure 1.3 Prince Roland Bonaparte’s salon, from the first issue of Femina (February 1, 1901).

The recurring second-person address also had the effect of fleshing out the alternative universe of the magazine. Not only were readers invited to see celebrated actresses and writers as alternate images of themselves, but they could also see better versions of themselves through their consoeurs, their fellow lectrices, who shared many qualities with their favorite celebrities. In April 1908, the novelist Marcel Prévost, a frequent contributor to Femina, accepted Pierre Lafitte’s invitation to offer a monthly chronique in which he would “con...