![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE MIGRATION OF ENTERTAINERS TO JAPAN

AMY TURNED EIGHTEEN YEARS OLD NOT long after I met her. At the age of seventeen, while many U.S. students are worrying over college applications or drivers’ license tests, at an age where anyone is considered “severely trafficked” under U.S. policy guidelines,1 she chose to leave her home to become a first-time contract worker in Japan. Amy fraudulently entered Japan with the use of another person’s passport, but no one coerced her or forced her to do so. Instead, it was Amy who was quite determined to secure a contract as an entertainer and venture to Japan before she turned eighteen years old to help her parents financially.2 Because all of her older siblings had gotten married quite early, Amy felt that this responsibility was left to her. She wanted to work in Japan for a few years to raise the funds that her parents would need to start a small business to support them in their old age.

Amy grew up as one of the working poor in Manila. Her fifty-six-year-old mother was a homemaker, and her father, whose age she did not know, hardly made ends meet with his daily earnings as a driver of a passenger jeepney.3 Like Amy, many entertainers are among the poorest of the poor in the Philippines. Many had to drop out of school prior to migration. While some members of the middle class pursue hostess work in Japan because they have a passion for singing and dancing, most enter this line of work to escape their lives of dire poverty. Many of the entertainers I met grew up having to pick through garbage for food, sell cigarette sticks in bus terminals, and clean car windows in heavy traffic. Amy peddled pastries at the bus stop for a local bakery. She considered migrant hostess work her most viable means of financial mobility. Without financial resources, most other migrant employment opportunities had been closed to her. For instance, she could not afford the US$3,000 to US$5,000 fee that recruiters charge prospective migrant domestic workers in Hong Kong or Taiwan.4 Yet, even if she could afford the fees imposed on domestic workers, Amy had no desire to become one, seeing their work as more difficult and dangerous than hostess work. For Amy, domestic work was made more perilous by the fact that it isolates the worker in a private home. Hostesses in Japan generally prefer their jobs over domestic work. Rikka, a veteran hostess, explained:

Well, the salary is higher. In Hong Kong, it is only maids there. The contract workers who come back from Japan wear nice clothes, and the ones who come from Hong Kong have bags made of boxes. The women from Japan wear Louis Vuitton, and they have big earrings. The women from Japan, they have impressive necklaces, as big as dog chains. [We laugh.] The people from Hong Kong and Saudi Arabia, they are callused. The people from Japan, their hands are milky.

While migrant hostess work is considered desirable, it is not easily accessible.

Prospective migrant hostesses must undergo a highly selective audition in which they have to compete with around 200 other women for a handful of slots to go to Japan. At the audition, which is held at various promotion agencies in Manila, prospective hostesses are not judged on the merits of their talent but instead on their looks. Prospective migrants do not have to sing or dance at an audition but must instead look more attractive than the scores of other women around them. The local staff of the promotion agency, along with a Japanese promoter who has flown to the Philippines for the sole purpose of finding entertainers to place at various clubs in Japan, physically evaluate prospective migrants at an audition, where women parade in front of them as they would in a beauty contest. The women do not have to speak except perhaps to say their name, age, and how many times they have worked in Japan as an entertainer. Return migrants are sometimes tested briefly on their Japanese language skills, but their skills need not be more than rudimentary. For instance, they at most would have to demonstrate that they know how to throw a compliment to a customer in Japanese.

Amy had to undergo an audition at least three times before she was finally chosen to go to Japan. She described her slew of auditions as a disheartening process, one in which she had to undergo a series of rejections that she only managed to survive with the emotional support of the woman who had designated herself as her “talent manager.” Amy’s manager basically acted as her job coach, teaching her how to dress and apply makeup. In exchange for her services, she would receive at least 50 percent of Amy’s salary, evidently not only for Amy’s first labor contract but apparently for her next six. On signing a contract to be one of her manager’s “talents,” Amy agreed to complete six contracts for the next few years; yet securing six job contracts to work as a hostess in Japan is not easy. Unless Amy would be requested at the end of her contract to return to her club of employment, she would have to go through another round of auditions in various promotion agencies in Manila. Amy would have to do so because migrant entertainers cannot work continuously in Japan; instead they must return to the Philippines between contracts.

Refusing to complete six contracts in Japan would incur Amy a sizeable penalty of at least US$3,000. Amy could avoid this penalty without completing six contracts if she tried but fails to secure a contract at an audition, which is a risk that managers knowingly take when investing on the “training” of prospective migrant entertainers such as Amy. But Amy would probably have to go to at least twenty more auditions and do poorly, for instance not be selected as one of the top twenty candidates in any of them, before her manager would release her from future bookings. The point is that managers do not easily release entertainers such as Amy from their long-term contracts.

It would not only be Amy’s manager in the Philippines who would be entitled to a portion of her salary. So would the promotion agency in the Philippines and the promoter in Japan. Between the two of them, they could legally obtain up to 40 percent of Amy’s salary. For a number of reasons, a club in Japan technically cannot employ Amy; as I will later explain, the promotion agency in the Philippines and the promoter in Japan were her official employers. In most cases, a club would usually pay the promoter and promotion agency the salary of entertainers such as Amy prior to their arrival in Japan, but they in turn would withhold this salary from the entertainer until her very last day in that country. In fact, Amy had yet to be paid a dime of her earnings after having already worked in Japan for almost four months. Instead, she would not be paid the wages given by the club owner to her promoter until she completed her contract. It is common practice for the promoter to pay entertainers such as Amy at the airport when they are about to depart for the Philippines.

To survive, Amy lived off the tips she receives from customers, the commissions she received every ten days for her sales, and a daily food allowance of 500 yen, or US$5, that she received from the club owner. Some advocacy workers in Manila have said that the practice of withholding wages forces entertainers such as Amy into prostitution. Regardless, the fact that her wages were withheld not only violates Japan’s labor laws but technically made her vulnerable to forced labor.5 Also leaving Amy vulnerable to abusive work conditions was the fact that her promoter had confiscated her passport soon after she arrived in Japan. The promoter told Amy that he would return the passport to her at the airport on the completion of her six-month contract. Having her passport and wages withheld not only discouraged Amy from quitting but technically made her an unfree worker.

Although Amy had not yet been paid her salary, she already knew that she would receive only US$500 on her last day in Japan. The Japanese government stipulates a minimum monthly salary of 200,000 yen (approximately US$2,000) for foreign entertainers, but the middlemen who brokered Amy’s migration are entitled to most of her salary.6 Under the terms and conditions of her migration, Amy agreed to allocate US$1,000 of her monthly salary to the promotion agency and promoter who arranged her migration, while a US$500 monthly stipend was earmarked for her manager in the Philippines. These terms left Amy with a monthly salary of no more than US$500. Yet Amy knew that she was going to return home to the Philippines with a cumulative salary of only US$500 for six months of work in Japan, which is far less than the US$3,000 to which she should have been paid after the completion of her contract. This was the case because Amy had been paid US$500 of her salary prior to migration, and she additionally accrued US$1,000 in debt to her promotion agency, which compounded to US$2,000 due to the 100 percent interest rate the agency placed on it. Amy incurred this debt to cover various migration-related expenses such as the passport fee, medical exam fee, and so on.

Migrating to Japan is not free, as prospective migrants eventually learn they must pay the promotion agency for the dancing or singing lessons they must complete to qualify for an entertainer visa along with the cost of their passport, police clearance, medical examination, and other government requirements. Amy had borrowed money to pay for some of these costs. Most if not all entertainers accrue some debt before they go to Japan for the very first time, but most are not saddled with an interest by promotion agencies or managers, as Amy had been.

Disgruntled by her small salary, Amy admitted to selectively engaging in paid sex with customers. She knows that solely relying on her salary would not get her far. Amy did have certain boundaries. She had sex only with customers whom she found physically attractive. She also never received a direct payment for sex; instead, she received gifts. Amy told me that she engaged in compensated sex so as to guarantee that she would amass some financial gain from her time in Japan. However, still somewhat constrained by the moral stigma attached to prostitution, that is, the direct payment of money for sex, Amy wanted to clarify that she did not engage in prostitution. Interestingly, some of Amy’s co-workers still ostracized her, as most of them would not engage in any form of commercial sex, suggesting that Amy’s actions are the exception and not the norm among Filipina hostesses in Japan. The nineteen-year-old Reggie, for instance, was saddled with an even larger debt than her co-worker Amy but could not be tempted to accept the US$100 tip offered to her by a customer in exchange for a French kiss. The third-timer Kay, who also worked with Amy, also could not get herself to go to bed with her frequent customer, despite his threat that he would no longer give her gifts of jewelry from Tiffany’s if she did not have sex with him after a month. The actions of Amy raise the question of whether she is a “severely trafficked person,” not only because she was under age but also because her salary reductions pushed her into sex work in the first place. Some would say yes, but Amy herself would say no and insist that it had been her choice to engage in sex with some of her customers.

THE PROCESS OF MIGRATION

In the last twenty-five years, a steady stream of migrant women from the Philippines has entered Japan with entertainer visas.7 These visas allow them to work as professional singers and dancers in Japan for a period of three months up to a maximum stay of six months. Because the government of Japan bans the labor migration of unskilled workers,8 the visas of entertainers restrict their employment to singing and dancing on stage.9 Their visas additionally bar them from interacting with customers because doing so would supposedly jeopardize the professional status of their jobs, as government officials fear that interacting with customers would mirror the activities of a waitress.10 Still, most if not all entertainers closely interact with customers. Most enter Japan knowing that their work will require they do so.

While the government of Japan worries that close interactions between entertainers and customers would threaten the professional status of entertainers as performance artists, the U.S. government argues that such interactions suggest their prostitution. In the 2004 TIP Report, U.S Department of State identified migrant Filipina entertainers as sexually trafficked persons, asserting that the “Abuse of ‘Artistic’ or ‘Entertainer’ Visas” is a vehicle “used by traffickers to bring victims to Japan.”11 Disregarding the factor of consent, the U.S. Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) defines sex trafficking as “the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person for the purpose of a commercial sex act.”12 This definition automatically renders any migrant sex worker a trafficked person, one who is assumed to be in need of “rescue, rehabilitation, and reintegration,” regardless of their volition.13

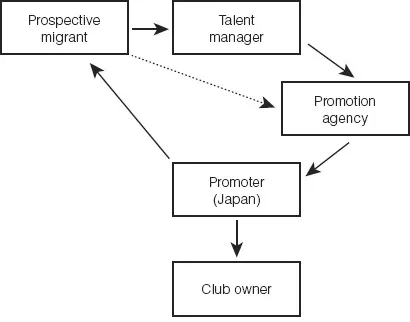

Migrant Filipina entertainers are susceptible to forced labor. Their vulnerability arises primarily from their relation of servitude to middlemen, some of whom have been legally designated to broker the hostesses’ migration. These include (1) the labor recruiter from Japan, otherwise known as the promoter, who places the entertainer at a club; (2) the local promotion agency in the Philippines, who makes sure that the terms of employment for hostesses abide by labor standards in the Philippines; and lastly (3) the talent manager, the self-designated job coach of prospective migrants whose responsibility is to increase the marketability and employability of prospective migrant entertainers.

Due to the presence of migrant brokers, going to Japan from the Philippines is not a simple process of moving from A to B for migrant entertainers. It begins with a prospective migrant signing on with a talent manager, who then takes the prospective migrant to an audition at a labor placement agency in the Philippines, otherwise known as a promotion agency, and the subsequent selection of the prospective migrant by what is called a Japanese promoter at the audition. The Japanese promoter then places the prospective migrant in a club in Japan without much input from the club owner. Notably, the club in Japan is not the employer of the migrant entertainer, even though the migrant entertainer is technically working for the club owner. Instead, the Japanese promoter and Filipino promotion agency are the employers of the migrant entertainer. What explains this complex migration process? (See Figure 1.1.) Why the need for brokers such as the promoter or promotion agency? Can migrant entertainers ever circumvent this process and negotiate directly with the club, that is, their workplace, in Japan? In what sort of dependent position vis-à-vis brokers does the current migration process leave migrant entertainers? By addressing these questions, I unravel the relationship of entertainers and migrant brokers, specifically talent managers, promotion agencies, and promoters, and explicitly describe the legally sanctioned relations of servitude that these brokers maintain with entertainers.

FIGURE 1.1 The migration process.

By calling attention to the role of middlemen in the process of migration, I am acknowledging the susceptibility of migrant Filipina entertainers to forced labor. My discussion establishes that a culture of benevolent paternalism shapes the migration of women, resulting in the state’s impulse to support their social and moral values with protectionist laws,14 including minimum age requirements, a stringent professional accreditation system, standards of employment, and broker regulation. Protectionist laws in Japan and the Philippines—laws that emerge from the state’s culture of benevolent paternalism—diminish women’s capacity to migrate independently because they leave the women dependent on middleman brokers. The word paternalism in the most recent Oxford English Dictionary (OED) refers to “the policy or practice of restricting the freed...