![]()

PART ONE

Introduction and Theory

![]()

ONE

Introduction

Perhaps the most significant aspect of Malaya’s success is that it was achieved not by separation of political power from development, but by an infusion of that power into the development effort.

—Gayl Ness1

The main challenge for Thai policy-makers is to work out a development strategy which will try to redress the social and regional imbalances existing in the society following a period of rapid economic growth. At the same time, however, a development plan to harmonize the objectives of growth with social justice also requires some kind of political and institutional structure which has a clear sense of purpose and which will be innovative enough to bring about the necessary reforms.

—Saneh Chamarik2

Without strong political institutions, society lacks the means to define and realize its common interests.

—Samuel Huntington3

Introduction

The pursuit and achievement of equitable development—economic growth rooted in a strong pro-poor orientation—is a rare feat. Most countries in the developing world have difficulty achieving economic growth, let alone growth with equity. Only a few countries across the world have achieved growth with equity. The most prominent have been in Northeast Asia—Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan—but a few others are sprinkled around different regions of the world, including Costa Rica, Mauritius, Kerala (India), and Malaysia.

In 1955, the economist Simon Kuznets hypothesized that economic growth would affect the level of inequality through a parabolic process.4 As the economy took off, inequality would rise but would then stabilize as the economy developed and finally decline at the more advanced levels of economic development. This was known as the inverted-U hypothesis. The Kuznets curve was compelling because it had a clear deductive logic at its core: intersectoral shifts between agriculture and industry would lead to rising inequality in the early stages of modernization. It also cemented analytically what seemed intuitive at the ground level: that there were significant costs to industrialization. Yet a review of the vast body of literature on the Kuznets curve concluded that there is in fact no necessary, logical relationship between economic growth and inequality.5 In some developing countries, economic growth has not inexorably led to rising inequality. What, then, distinguishes the rare cases of growth with equity from those with growth and inequity?

This is a general theoretical question that can be addressed from different angles, including through large-N statistical studies focused on economic variables; case studies emphasizing particular economic, political, or sociological characteristics of a country; and comparative studies seeking to highlight specific factors that account for different developmental trajectories. In this book, I employ the latter strategy. I propose to answer the general theoretical question of variation in patterns of inequality through a comparative historical analysis in which political institutions, especially institutionalized political parties and cohesive interventionist states, play a central role in shaping outcomes of development.6

The central thesis of this study is that institutional power and capacity, along with pragmatic ideology, are crucial to the pursuit of equitable development. Institutionalized, pragmatic parties and cohesive, interventionist states create organizational power that is necessary to drive through social reforms, provide the capacity and continuity that sustain and protect a reform agenda, and maintain the ideological moderation that is crucial for balancing pro-poor measures with growth and stability. Strong institutions are the political foundations for equitable development because they ensure that public interests supersede private interests. Central to the politics of social reform must be the creation of institutions that are centered on representing collective goals rather than personalistic ones.

This book advances this thesis through a structured comparison of two relatively similar countries in Southeast Asia: Malaysia and Thailand. The study explains why Malaysia has done significantly better than Thailand in achieving equitable development. It takes a comparative historical approach to the problem, emphasizing the roots of inequality in both countries and the institutional structures that have emerged to address the dilemma of inequality. The book then places the comparative analysis of these two countries within a broader framework of two other Southeast Asian cases, the Philippines and Vietnam, two countries that also represent different points on the spectrum of equitable development, with the Philippines demonstrating lower levels of success like Thailand, and Vietnam being more similar to Malaysia.

The Puzzle and the Argument

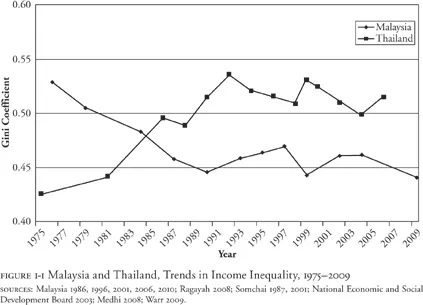

In Southeast Asia, Malaysia stands out as the most successful case of equitable development. In terms of growth in gross domestic product (GDP), Malaysia has outpaced its Southeast Asian neighbors (Singapore excepted), with a 2009 per capita GDP of US$7,030.7 Poverty fell from a high of 49.3 percent in 1970 to as low as 3.8 percent in 2009.8 Most critically, Malaysia’s Gini coefficient declined from a peak of .529 in 1976 to .441 in 2009.9 By 2005, less than a quarter of the population was working in the traditional agrarian sector.10 Within the context of the Southeast Asian newly industrialized countries (NICs), Malaysia has led the group in GDP per capita, poverty reduction, and income distribution.

What especially distinguishes Malaysia is its sharp reduction of income inequality. No other country in the region has been able to significantly reduce the uneven distribution of income in the context of high growth rates. Although Malaysia’s distribution of income rose in the 1990s, when viewed in the long term, the trend has been a significant decline in income inequality largely through the evening out of interethnic disparities. In the context of the debate regarding the relationship between growth and equity, Jacob Meerman writes: “[H]ere is a case [Malaysia] where social policy may have been the instrument that made growth at all possible.”11

Thailand’s development has been impressive in terms of growth rates. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Thailand’s galloping growth rates set records in the developing world. With an average growth rate of 9 percent during the boom years from 1985 to 1995, it succeeded in lowering poverty to 11.6 percent before the eruption of the Asian financial crisis in 1997.12 In 2009, its GDP per capita stood at US$3,893.13 Yet what stands out in Thailand’s developmental trajectory beneath the impressive growth statistics is the stark rise in inequality. In 1975, the Gini coefficient was .426; by 1992, it had peaked at .536. From 1992 to 1998, the Gini coefficient dropped to .509, but in 1999, it had risen back to .531. In 2004, it declined slightly to .499, but in 2006, it was .515.14 In essence, from the mid-1980s until 2006, the Gini coefficient has moved upward, despite a few years of slight decline, but has generally hovered around or greater than .50. Between 1981 and 1992, the period during which the boom began and a democratic transition occurred, the average income of the top 10 percent of households tripled, whereas the income of the bottom 30 percent of households registered little change. The gap between the top and bottom income groups widened from seventeen to thirty-eight times.15 And despite high growth rates, Thailand’s social structure has not changed as much as Malaysia’s, with between 40 percent and 50 percent of the population still employed in the agrarian sector. These trends in inequality stand in stark contrast with those of Malaysia, where the Gini coefficient has decreased since 1976 (see Figure 1-1). “Nowhere in Southeast Asia, or even in Asia, has this twin problem of growth-equity trade-off become more unique and more interesting than in the case of Thailand,” observed Medhi Krongkaew, an economist who has studied Thailand’s distribution of income throughout his career.16

Given these different trends in equitable development writ large, this empirical puzzle therefore arises: why has Malaysia done much better than Thailand? In Malaysia, a highly institutionalized ethnic party, the United Malays National Organization (UMNO), has forcefully sought to implement pragmatic social reforms along ethnic lines. Along with a capable bureaucracy, it has advanced a battery of policies that have gradually reduced the uneven distribution of income between the Malays and the Chinese. By contrast, Thailand has been devoid of institutionalized parties with programmatic agendas. Its bureaucracy has stimulated high growth rates but has remained largely aloof with respect to the concerns of the popular sector. Strong institutions—especially institutionalized parties and effective interventionist states—are thus key to the pursuit of equitable development.

In Malaysia, the problem of inequality has deep roots that go back to the British colonial policy of “divide and rule.” Colonial authorities divided the economy across ethnic lines, relegating the Malays to traditional economic sectors while giving the Chinese free rein over the more modernized areas of the economy. This ethnic division of labor became deeply entrenched in the Malaysian soil, aggravating Malays’ anxieties that their status in a land that they believed belonged to them was under grave threat. This came to a head in devastating ethnic riots in Kuala Lumpur on 13 May 1969.

Breaking through structural inequalities compounded by ethnic divisions is not an easy task. Countries facing similar problems and with comparable demographics have been consumed by ethnic violence (Guyana), civil war (Sri Lanka), and cyclical coups (Fiji). Malaysia, however, was able to tackle ethnic and class divisions through a combination of party organization, state intervention, and moderate policies of redistribution. Institutional resilience has been crucial to Malaysia’s ability to address social reforms without destabilizing the polity. An institutionalized party has been able to channel grievances from the grass roots into the policy arena, to maintain a consistent focus on its programmatic agenda, and to monitor the implementation of policy in the periphery. This institutional depth provided Malaysia with the political foundations for wide-ranging social reform.

Ideological moderation has been a crucial element of Malaysia’s reform agenda. Although UMNO was born of anxieties of ethnic survival and has upheld a strong ethnic raison d’être throughout its history, its policies and political behavior have not been characterized by ethnic chauvinism or violence against rival ethnic groups. The Malaysian state has used authoritarian measures within a semidemocratic environment since 1969 to enforce its redistributive agenda, and it has discriminated against the large Chinese minority. The politics of equitable development in Malaysia has not come without costs. But on a comparative level, these authoritarian tactics have not been as severe as in other countries facing the same problems of ethnic inequality, such as Fiji or Guyana; nor have the policies been so draconian as to completely marginalize the ethnic minority and drive it to wage war for a separate state, such as in Sri Lanka. Furthermore, in its redistributive mission, the Malaysian state never seized assets through a nationalization program like that of Venezuela under Hugo Chávez.

In Thailand, inequality can be traced to a pattern of laissez-faire growth, in which incomes from export-oriented industrialization have heavily outpaced incomes from agriculture. Compounding this income differential has been the slow pace of labor absorption in modern industry, where the rural sector’s decline as a share of GDP has not been matched by a similar decline in the rural population. Although industrialization has taken off, about 40–50 percent of the population still remains within the rural sector. Compared with countries with a similar GDP share of industrialization to agriculture, Thailand’s failure to absorb the rural population in the modern sector is striking. A tendency to concentrate economic resources in the capital, Bangkok, also exacerbates this imbalance. With the recent exception of the Thai Rak Thai (TRT) Party, no political institution has emerged in Thailand to fundamentally tackle uneven growth and rural-urban disparities.

Unlike Malaysia, in Thailand personalism has largely shaped political parties. Parties have not stood for public agendas but rather for private interests. Most parties have had shallow organization, amorphous ideology, and brief life spans. They have therefore lacked the motivation and the capacity to represent the poor or any collective group. Furthermore, a conservative bureaucracy has dominated policy making, and the military has perennially intervened in the affairs of civilian politics, thereby preventing the sustainability of any social reforms. Despite having achieved some of the highest growth rates in the world, Thailand also experienced a severe worsening of its distribution of income. Most notably, the democratic transition dating from 1988 led not to improvement in the distribution of income but to its worsening.

The populist policies of the Thaksin Shinawatra government (2001–06) and the TRT Party were a notable effort to incorporate the interests of the poor and change the trajectory of Thailand’s development model. For the first time, a slew of pro-poor policies, ranging from universal health care to a debt moratorium for farmers, was implemented in an organized and sustained manner. But with the exception of the universal health-care program, these policies did not make fundamental changes in the livelihoods of the poor. Although some of the spending programs provided the poor with short-term opportunities to reduce their debt or to engage in small-scale entrepreneurship, the long-term effect does not appear to have been sustainable in terms of significant advancements in capacities and in income. This is, in part, because some of these policies represented the party’s more populist orientation.

Analytical Contributions of the Study

This book intends to make several contributions to the study of the comparative politics and political economy of developing nations. First, the book emphasizes the importance of political institutions, especially institutionalized parties, in effecting equitable development. Institutionalized parties are crucial to the reduction of inequality because they provide the “organizational weapon” necessary for a state to implement social reforms.17 Institutionalized parties back reforms with organizational power, sustain policy continuity, maintain dialogue with the grass roots, monitor the bureaucracy’s implementation of policy, and emphasize programmatic policies rather than personalistic and clientelistic exchange. All of these factors are necessary for advancing social reform. Above all, an institutionalized party reinforces the importance of public over private interests. Without institutionalized parties, a state with some ...