![]()

Part I

THE BASICS

Leading in the Face of Disruption

![]()

Chapter 1

TODAY’S INNOVATION PUZZLE

You have the talent in large organizations. You have the resources in large organizations. So why can’t they be more innovative?

SAM PALMISANO, FORMER CEO, IBM

HOW LONG DO YOU EXPECT TO LIVE? Most Americans can plan on reaching the age of seventy-nine, Japanese almost eighty-three, Liberians only forty-six. Now, how long will your company live? It turns out that it’s a lot less than you are to make it to a ripe old age. Research has shown that only a tiny fraction of firms founded in the United States will make it to age forty, probably less than 0.1 percent.1 Of firms founded in 1976, only 10 percent survived ten years later. While this is somewhat understandable because of the high mortality rate of newly founded firms, other research has estimated that even large, well-established U.S. companies (maybe like the one you work for) can expect to live only between another six to fifteen years on average.2 Underscoring the fragility of organizational life, McKinsey colleagues Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan followed the performance of 1,000 large firms across four decades. Only 160 of 1,008 survived from 1962 to 1998.3 They found that in 1935, the average company could expect to spend ninety years in the S&P 500. By 2005, this average had fallen to a mere fifteen years—and it continues to fall. On average, an S&P 500 company is now being replaced about once every two weeks—and this rate is accelerating.4 One-third of the firms in the Fortune 500 in 1970 no longer existed in 1983. This led one researcher to observe that “despite their size, their vast financial and human resources, average large firms do not ‘live’ as long as ordinary Americans.”5

Why should this be? We understand why our human life is limited. Studies have shown that over time, our body’s cells lose their ability to accurately regenerate themselves. Cell senescence is at the root of many of the diseases that limit our life span. But there is no obvious equivalent cause of death for organizations. When we humans are successful, we may eat too much, work too hard, exercise too little, and do a variety of things that are not good for our health. But even the healthiest among us will succumb to cell senescence. By contrast, when companies are successful, they amass all the resources needed for their continued reign. They generate financial strength, market insight, loyal customers, brand awareness, and the ability to attract and develop human capital. Used wisely, these advantages should enable them to continue their success as markets and technology evolve. Unlike us, companies have no obvious biological limitations to their continued success. Yet even successful organizations have a disturbing tendency to perish.

Consider Netflix and Blockbuster. In 2012, Fortune magazine featured Reed Hastings, Netflix founder and CEO, as its businessperson of the year. Founded in 1999, Netflix is now the world’s largest online DVD rental service and video streaming firm, with more than 100,000 titles in its library, 60 million subscribers, and annual revenues of more than $4 billion. In 2002, the year Netflix went public, prime competitor Blockbuster had revenues of $5.5 billion, 40 million customers, and 6,000 stores. Yet only eight years later, on September 23, 2010, Blockbuster filed for bankruptcy; in a supreme irony, Netflix was added to the S&P 500 shortly after, replacing Eastman Kodak, another failed corporate icon.

When Netflix went public in 2002, a Blockbuster spokesperson said that it was “serving a niche market. We don’t believe that there is enough demand for mail order—it’s not a sustainable business model.”6 In 2005, as Netflix began moving into the streaming of videos over the Internet, the chief financial officer of Blockbuster said, “We don’t think the economics [of streaming] works well right now.”7

But before these public dismissals, there was a private one. In 2000, Reed Hastings flew to Dallas to meet with the senior executives at Blockbuster. He proposed that they purchase a 49 percent stake in Netflix, which would then become the online service provider for Blockbuster.com. Blockbuster wasn’t interested. Blockbuster didn’t have to buy Netflix—though it could have—to rent videos by mail. It had all the resources needed to crush a freshman firm that had revenues of only $270,000 and was a fraction of Blockbuster’s size when it went public. But by the time Blockbuster got around to renting videos by mail in 2004, it was too late.

Why did Blockbuster fail and Netflix succeed? The difference boils down to how their leaders thought about change. Blockbuster leaders were focused on growing and running today’s business: video rentals through conveniently located stores. And they were good at this. Their strategy focused on growth in new markets, increasing penetration in existing ones, and maximizing the number of movies rented. In 2003 Blockbuster had a 45 percent market share and was three times the size of its closest competitor. In 2004, as Netflix was becoming an even bigger threat, Blockbuster revenues still increased 6 percent and senior executives talked proudly about “the experience of a Blockbuster store.” In addition to extracting revenues from their existing business, the company saw opportunities for expansion through acquisitions (e.g., Hollywood Video), methods for boosting rentals, and the creation of a DVD trade-in program. Their decision to enter into the mail order and online rental business was reactive and defensive, not proactive and transformational. In hindsight, we can see that they focused on winning a game that was soon to be irrelevant.

In contrast, leaders at Netflix didn’t think of themselves as being in the DVD rental business; rather, they identified their offering as an online movie service. In Hastings’s words, “I was obsessed with not getting trapped by DVDs the way AOL got trapped, the way Kodak did, the way Blockbuster did. . . . Every business we could think of died because they were too cautious.”8 Even though their mail-in rentals caught on first, they’ve been focused from day one on how to be a broadband delivery company. “It was why we originally named the company Netflix, not DVD-by-mail.”9 The Netflix strategy emphasizes value, convenience, and selection. To deliver on these, they have been willing to cut prices and invest aggressively in new technologies ($50 million in 2006–2007 in video on demand). More important, they have been willing to cannibalize their old business to succeed in the new.

Video streaming puts Netflix revenue from DVD rentals at risk. Yet its leaders needn’t fear because they have been aggressive in moving into streaming; today more than 66 percent of Netflix subscribers use streaming, and the company has retained customers who might have otherwise moved to Hulu, HBO, or another of their many competitors. In Hastings’s view, DVD rental by mail is just one phase of the business. His goal is to have every Internet-connected device capable of streaming Netflix videos. To accomplish this, Netflix gives away the enabling software and is now on more than two hundred devices. In making this transition, Netflix is beginning to close some of its fifty-eight regional mail order distribution centers. While subscription rates for online service are lower than for DVD rentals, Netflix is beginning to save some of the $700 million that it spends for mailing DVDs. In the process, it is still growing its customer base by close to 50 percent every year.

More recently, in order to attract and maintain customers, Netflix has moved into video production and in 2015 will spend $6 billion in producing hit shows like Arrested Development and Orange Is the New Black. In producing original programming, Netflix is not seeking short-term profits but playing a game for the long haul. In the words of chief content officer Ted Sarandos, Netflix wants “to become HBO faster than HBO can become Netflix.”10

What was it about Netflix and its leadership that helped the firm transition from DVD rentals to video streaming, while Blockbuster and its management struggled and failed? This is the puzzle that is at the heart of our book. It’s a puzzle that we have been working on with companies from around the world for the past ten years in our research and consulting.

Organizational Evolution

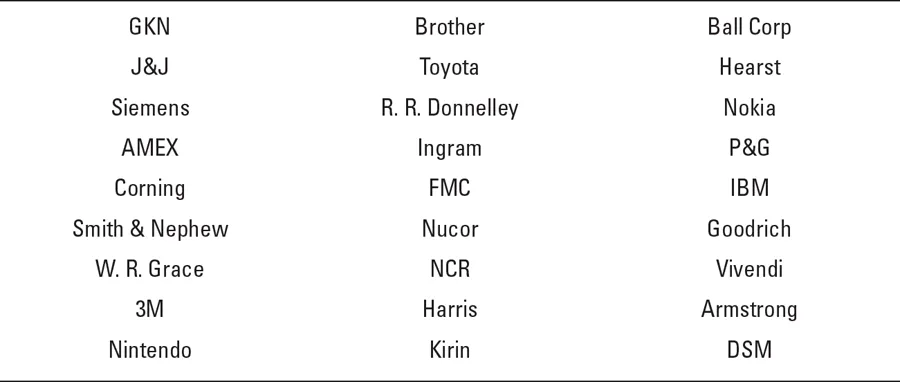

To get a sense of just how common this problem is, take a look at the companies listed in Tables 1.1 and 1.2 and ask yourself: What is the difference between those in the first table when compared to those in the second?

TABLE 1.1 What Is True of All These Companies?

TABLE 1.2 What Is True of All These Companies?

Table 1.1 lists a set of companies, some large and well known, like IBM, Toyota, and Nokia, and others less well known, like GKN, DSM, and the Ball Corporation. As you scan this list, ask yourself: What do these companies have in common? It isn’t obvious since they come from around the world and represent a hodgepodge of industries. But if you think more deeply, a couple of patterns will emerge. First, these are old companies. The average company on this list is 130 years old. They’ve all been around for a long time. Only a few were founded in the twentieth century (e.g., IBM, Marriott, Toyota, 3M, and DSM). Some are genuinely old. GKN, for example, is a British aerospace company founded in 1759. Think about that for a second: How could a firm founded in 1759 be an aerospace company? The Wright brothers didn’t make their first flight until December 17, 1903.

This leads us to the second truth about these companies—and the part that is most relevant for leaders today. All of these have been able to transform themselves to compete in new businesses as markets and technologies have changed. GKN began as a coal mine and then, with the industrial revolution, became a producer of iron ore. By 1815, it was the largest producer of iron ore in Great Britain. In 1864 it began to produce fasteners (nails, screws, and bolts) and by 1902 was the world’s largest producer of these. Drawing on its expertise in metal forging, GKN began to produce auto parts and then aircraft components in 1920. In the 1990s, the company sold off its fastener business and began to provide services as an industrial outsourcer to firms like Boeing. Today it is a $9 billion corporation competing successfully in aerospace, automotive, and metallurgy and employs more than 50,000 people. These transformations and their successes have been possible only because of leaders who were able to foresee how the company could leverage its strengths as markets changed.

BF Goodrich is best known as a maker of automobile tires, but it began by making fire hose and rubber conveyor belts in 1870 and parlayed its expertise in the manufacture of rubber products into automobile and aircraft tires, and then into high-performance materials. In 1988 it sold its tire business. By 2000 it was a $6 billion aerospace firm employing 24,000 people and selling engineered products and systems to the defense and aerospace industries. In 2012, it was purchased by United Technologies. W. R. Grace is a $2.5 billion maker of specialty chemicals, but it was founded in 1854 to ship bat guano (a fertilizer) from Latin America to the United States. DSM (Dutch State Mines) was founded 112 years ago as a state-owned coal mine. Today it is a life sciences and material sciences company. When it was founded in 1913, IBM made mechanical tabulating machines. Today it is a $100 billion company that earns 85 percent of its revenue from software and services that didn’t exist even fifty years ago. Kirin, the Japanese beer company, founded in 1885, is leveraging expertise in fermentation to become a producer of biopharmaceutical and agricultural products. Hearst, the eponymous publisher, was founded in 1887, but today more than half of its revenues come from electronic media; it is a growing business while most media companies are failing.

We could expand this list to include a large number of younger companies that have also been transformed. EMC, the $14 billion maker of storage products, began selling office furniture in 1979. Today it is morphing from a maker of computer hardware into a software developer and has recently been acquired by Dell. R. R. Donnelley began 150 years ago as a printing company and today is using its core technologies to move into the fast-growing business of printed electronics (e.g., RFID tags). Amazon, famous as an online book seller, is now the largest web retailer and a major player in the provision of cloud-based utility computing. Xerox is moving aggressively from selling machines to becoming a service company. Who knows what Google will become in the next decade?

To put a finer point on what is remarkable about these companies, we must consider how they have been able to successfully transform over time. Each of these businesses was able to capitalize on its dynamic capabilities: “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments.”11 As a result, they have been able to compete in both mature businesses (where they can exploit their existing strengths) and new domains (where they have leveraged existing resources to do something new). As their core markets and technologies changed, they have been able to change and adapt rather than fail. They have built bridges to their next destinations as the footing under them was quaking. How were they able to do this?

The short answer, which we elaborate on in the rest of the book, is that they had ambidextrous leaders who were able and willing to exploit existing assets and capabilities in mature businesses and, when needed, reconfigure these to develop new strengths. We’re talking about Netflix’s ability to invest in video streaming and rent DVDs by mail; IBM’s capacity to sell large mainframe computers (the z-series server) and do strategy consulting; Cisco’s success in selling routers and switches to large corporations and developing its high-end videoconferencing product, TelePresence. This is the positive side of the story we tell.

Now, look at Table 1.2 again and ask yourself: What’s true of these firms? What is most striking is how well known many of these names are: Sears, Polaroid, Firestone, RCA, Kodak, Bethlehem Steel, Smith Corona. These are (or were) great brands. They were compa...