![]()

CHAPTER 1

Preparing Tea

Spaces, Objects, Performances

To the foreign eye, the tea ceremony may seem unavoidably Japanese: a kimono-clad woman kneeling on tatami mats, gracefully preparing the beverage by means of a dense array of arcane procedures. But to outsiders, much in Japan is read as an expression of a foreign culture, from the politely crowded subways, to the exquisite yet simple aesthetics of prepared food, consumed with the eye before the mouth. For Japanese, most of these experiences are taken for granted as simply how things are done—people are more concerned with getting on the subway and getting fed than reading a cultural specificity into their activities. Yet even to many, accustomed to the quick preparation of simple green tea, consumed on tables and chairs while sporting Western clothes, the tea ceremony often connotes the traditional and evokes images of a fading cultural heritage. How is it that for the Japanese in Japan, where Japaneseness can be taken for granted, such an experience can be maintained?

Japaneseness within Japan

Delaying for a moment the question of origins—where these national inflections came from—which will be addressed in the next chapter, let us consider the positioning of the practice. The tea ceremony does not serve the work of signifying Japaneseness alone, but is situated within an assemblage of other practices and objects that also represent this diffuse concept—a cultural matrix, as Tim Edensor terms it, that “provides innumerable points of connection, nodal points where authorities try to fix meaning, and constellations around which cultural elements cohere.”1 The complexity and reciprocity of these associations give rise to the “nebulous condensation,” to use the words of Roland Barthes, that is Japaneseness.2 Some items of the matrix display qualities akin to those of chanoyu—such as the delight in asymmetry found in flower arrangement—while others offer contrasts, as in the military self-sacrifice of Nitobe’s bushidō. In this interconnected field, the tea ceremony occupies a privileged position, for it alone combines so many different practices and objects of the assemblage—clothing, cuisine, craft—into what its theorists describe as a “cultural synthesis.”

A second axis of connection and contrast weds national meanings to the doing of tea. For the ceremony is at once an expression of the rhythms and aesthetics of ordinary existence, and detached from such unreflective lifeways as a consciously focused objectification of what is traditionally Japanese. It is through the alternation of parallels with and contrasts to common features of everyday life in Japan that tea condenses the nation. Barthes described a similar process when he remarked of houses in the Basque region of France that they do not strike the eye as particularly Basque in their local setting. But transposed to Paris, in a simplified, clarified form omitting many of the practical details (the barns, the external stairs) that made them functional dwellings in their homelands—such houses impose their Basqueness on the viewer.3 In modern urban Japan, women in kimonos kneeling on tatami-mat floors invite a similar gaze. The Japaneseness encoded in tea places, captured in tea objects, and patterned into tea movements can be interpreted and experienced as quintessentially Japanese by the Japanese themselves because it is different—but not completely removed—from mundane aspects of life unmarked with national significations.4 As we shall see, the apartness and deliberateness of the tea room and the objects and actions within it concentrate and purify aspects of the community diffusely lived elsewhere, but bent through the prism of tea. In Barthes’s telling terms, the Japaneseness of chanoyu is “neither a lie nor a confession: it is an inflection.”5

How tea “just is Japanese” can be conveyed by taking a tour of an actual tea room. We will begin by examining how its architecture molds the body into recognizably Japanese forms and corresponding sensory experiences, and go on to look at the objects used in tea practice and their cultural significations. Finally, we will greet the practitioners in a chanoyu performance.

Tea Spaces

The tour begins at the tea complex Mushin’an,6 designed by a successful architect in the early 1990s for his daughter, a tea aficionado, who was delighted when her father converted her apartment into a compact but versatile tea complex as a marriage gift. Adhering to the numerous detailed standards of tea architecture, Mushin’an has not only appeared in magazines, but is also rented by high-ranking teachers for their classes. Many lessons do not take place in such authentic spaces—what practitioners emphatically label real tea rooms—and teachers hold classes in their homes or public tea rooms at community centers or schools. When “making do” in these cases, adjustments are often accompanied by apologies, measured against standards represented by places like Mushin’an. Thus even if not a typical example, this tea complex is a good example, for its seriousness—as well as that of the lessons that take place inside it—renders in sharper detail the ideal to which tea practice is held.

Mushin’an is tucked away in Roppongi, one of Tokyo’s many hubs, known as a center for consulates and foreign businesses and as a popular nightlife district. Emerging from the subway, one is beset by ten-story high-rises lining the street and an elevated highway blocking the sun. The megalithic Mori Building—symbol of the decadent Tokyo architecture planned during the economic bubble of the 1980s that combines shopping, working, and entertainment—beckons in one direction, and Tokyo Tower, a red steel TV transmission station inspired by Eiffel’s Parisian creation that serves as an architectural symbol of the city itself, guides the way to the tea room. Visiting a lesson on a Saturday morning may require dodging a few still-drunk revelers emerging from one of the numerous nightclubs and bars that dot the district. During the week, however, one is more likely to weave through the packs of shoppers and workers overfilling the sidewalks while trying to avoid volunteers requesting charity donations stationed at the subway entrance. A short distance down the street, the tea room is tucked away in an unremarkable multistory building, a few signs advertising the businesses inside speckling its narrow front, just like most edifices in the neighborhood. It is hard to imagine from street level that a tea room complex would occupy a significant part of the top floor in a building shared with a restaurant, an architectural firm, and a dance school. The owner of the complex even commented once on the strange juxtaposition as we walked to the subway station. “I sometimes wonder what is normal and what is not normal when I’m going between the tea room and here. Is this really everyday life? Sometimes the tea room seems so much more normal.”7

The urban infrastructure of Roppongi, Tokyo

Entering the building, the ground floor with its narrow hall, linoleum tiling, row of mailboxes, and potted plant looks like any other small, multipurpose office building. Up the elevator to the eighth floor and a short trip down the hall, the standard gray outward-swinging metal doors give way to a wooden lattice portal that slides to the side with the garagaragara sound often mimicked in traditional rakugo comedy sketches.8 Visitors are greeted by the name of the tea complex, engraved in flowing calligraphy written horizontally in the traditional style of right to left on the wooden name plate that hangs on the wall opposite the entrance.9 The three characters of Mu-shin-an, or Hut of the Empty Spirit,10 are followed by the signature of the Urasenke iemoto, who christened the complex with this Zen-infused name. Only tea rooms meeting standards of excellence are granted an appellation by the iemoto, an honor applied for, and subsequently compensated for, with thousands of dollars in financial contributions.

In the small entrance space, guests leave their shoes on the slate flooring before rising up on a single wooden step and then onto the tatami mats that cover the floor of much of the complex. While most modern shops and businesses have done away with formal entranceways, a change in elevation between the threshold where shoes are removed and the interior proper is still common in many houses, restaurants, and schools, though the difference is typically a mere five inches or so. However, like many older or traditional buildings where the change is much greater, Mushin’an includes a long wooden step to bridge the almost 1.5-foot gap between the levels, and on which shoes may be set for guests about to depart. Because the distance is so large, brief greetings that do not require the visitor to enter the complex are met by the person on the interior kneeling rather than standing. When tea sweets are delivered, for instance, the difference in height beckons the person collecting the parcel to move to the floor or else tower awkwardly over the deliverer. Kneeling at the entrance—a scene invoking hospitality sometimes featured in tourist brochures at traditional inns11—is not only considered the most polite way to greet people at the door, it is almost required by the feeling of space. And once on the ground, a formal bow, rather than a polite head-nod, flows easily from the body as the hands slide from the lap to the floor.

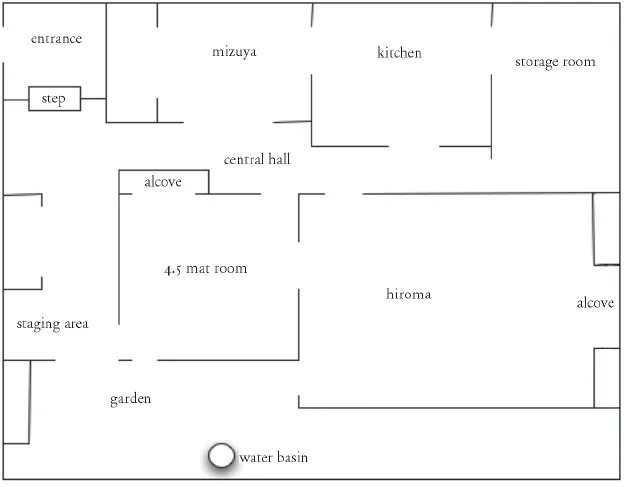

The complex itself is constructed in an interlocking layout, with every room connected to others by at least two doors—an openness that facilitates the adaptation of the space for multiple purposes. Proceeding through the entrance, one comes to a narrow room with shelves for storing coats and bags, and a hook on the wall where a scroll might be hung if it is transformed into a waiting area during a formal tea gathering. The space—like most tea spaces—remains empty unless in use, but the absence of objects draws attention to how it is enclosed. The walls are made of high-quality kabe, a mixture of clay and sand that was a staple in building construction before plaster—easier to install and less prone to cracking—came to cover most walls after the Second World War. Along one side, the textured, earthen comfort is disrupted by a set of sliding doors connecting the space to a small tea room. The off-white papered portal is dotted by elegant pearl-colored prints of a chrysanthemum and paulownia pattern—a traditional combination that the knowledgeable will identify as popularized by the sixteenth-century warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

A second sliding door—this one of translucent rice paper stretched across a wooden lattice that stages a play of shadows when the sun is shining—leads out to a small garden.12 Here a flood of light greets visitors through a floor-to-ceiling wall of glass defining outdoor and indoor sections. Bearing little resemblance to the typical rooftop or yard packed with flowers and carefully sculpted trees, the tea garden is laid out on a bed of round pebbles strewn with irregularly shaped stepping stones that are interspersed with islands of small plants and moss. At the visual center stands a large stone basin, about two feet tall, and kept constantly full by the slow drip of water from a bamboo fountain. To the side sits a simple wooden bench where guests attending a formal tea gathering wait until invited to enter the main tea room.13

Floor plan of Mushin’an

A guest at a tea gathering entering the garden

When the garden is in use, an earthy scent creeps into one’s awareness from the slowly evaporating water sprinkled judiciously across the stones and path—a symbol of welcome still performed outside some storefronts and restaurants, particularly in Kyoto. Because the guests have left their shoes at the main entrance, sandals of woven straw are provided for traversing the uneven stepping stones. These are slipped on and worn with relative ease by those in a kimono, their split-toed socks fitting snugly into the thong-style slippers, though guests in Western clothes wearing socks usually have a more difficult time both putting on—and keeping on—the slippery straw sandals. Still, they manage to walk to the stone basin, where they purify their hands before entering the tea room. Here they encounter a bamboo scoop placed diagonally, the cup resting on its side, across the basin for their use. Almost all Japanese will have some familiarity with ladling water to purify the hands and mouth, a symbolic activity carried out whenever visiting a shrine. But at these sites less attention is paid to the fine details of movement than is demanded in the tea ceremony, where novices are instructed in how to hold the ladle to pour water over their left hand, their right hand, and then into a cupped left hand to use in rinsing the mouth. Afterward they may be gently reminded to return the scoop as they found it, on its side.

Two tea rooms stand at the core of the complex, a 4.5-mat room—the nine feet by nine feet classic size of a tea space—and a larger 8-mat room, or hiroma.14 A sense of confinement in the smaller chamber is moderated by the numerous doors leading into it: two sets of sliding panels connect it to the waiting hall and to the larger tea room, a diminutive white papered door used by the host leads to the preparation areas, and an opening so narrow that one must crawl through it—a classic symbol of a tea room—leads to the garden. Explanations at temples and in history books, as well as by tea practitioners themselves, often point out that the crawl-through entrance was initially designed so small (approximately 28 by 28 inches) that samurai were forced to remove their swords before entering the tea room, symbolizing the equality of all in the space. More immediately consequential than its historical associations, the crawl-through door compresses the body such that, when entering, one is automatically positioned to kneel on the floor, the space spreading ahead with a deceptive impression of capaciousness. The transition between the inside and outside, created by the momentary tunnel, thus provides a smooth segue into the sensory and behavioral orientations of the tea world.

Defining the room is an alcove built into a wall and used for display—typically an arrangement of flowers resting on the slightly raised floor under a scroll inked with the bold characters of a terse Zen phrase. Once considered such a central part of interior architecture that debates raged on whether these recesses—superfluous from a utilitarian point of view—should be included in the public housing hastily erected on the rubble of World War II, alcoves have become less common in recent years.15 Along with sliding doors, tatami mats, and clay walls, alcoves are a definitive element of washitsu, literally “Japanese rooms,” found in homes, restaurants, and hotels.16

The crawl-through entrance of a tea room built within a room at a hotel

The alcove marks the upper end of a nonlinear hierarchy of positions that locates all guests on a scale of importance, anchored at the other end by the host’s door. Such negotiated orders of interior space may be disregarded in more mundane aspects of daily life, but still appear in both business and formal etiquette.17 Trainees at large companies will learn the “high” and “low” positions in a waiting room or car, and are expected to develop a subtle skill for sliding toward the control panel marking the most honored place within an elevator to hold the “open” button for a social superior. Tea gatherings, however, stand out for the degree of deference displayed. Guests do not simply assume a seat, but position themselves in this unequal space through active, energetic (and even tiresome) negotiations. Experienced practitioners are remarkably adept at displaying the much-lauded value of modesty by situating themselves on the lower rungs of the spatial hierarchy—an inversion that even newcomers know not to tolerate. At larger gatherings these “no, after you” refusals can continue for so long that the host may step out and appoint a guest to the place of honor.

If one is standing, it is not hard to notice the wooden ceiling, which looms lower than in the rest of the complex. Over the guests’ area rest patterned slats of wood, their upward slant contributing a sense of spaciousness while maintaining intimacy. A second section made of unfinished branches hangs flat above the place where the host sits. Hovering close to anyone standing up in the space, the low-lying ceiling prescribes a seated position as the most comfortable. Indeed, anyone app...