![]()

Section 1

Institutions and Living Standards

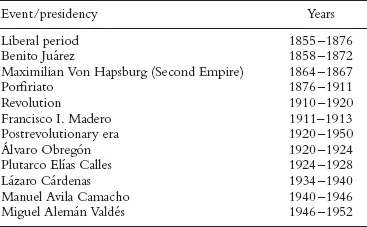

The problem of poverty all but defines modern Mexican history. This section therefore traces the origins of poverty alleviation, including social welfare programs from the mid-nineteenth century until 1950, from the time, that is, when Mexico was a preindustrial and rural nation to a period of rapid industrialization and urbanization. During the same period, Mexico underwent deep social and political transformations due to civil wars, foreign invasions, and a thirty-five-year dictatorship, among other significant events (see Table 1).

The purpose of this section is to answer one of the questions posed in the Introduction of this book: how efficient institutions in charge of social welfare were in fulfilling their mission statement over time. It does so by explaining from a long-term perspective how the issues of poverty and the needs of those at the bottom of the social scale were addressed by the authorities in power. To tackle this goal we need to survey the evolution of ideas, mentalities, and objectives that informed the design of policies concerning welfare and then assess how they were adopted in Mexico.

As industrialization gained importance in the growth and development of the Mexican economy, so did the role of the industrial proletariat in the design of welfare institutions. Concomitant to the process of industrialization and changes in the productive process were the ongoing debates around what welfare provision entailed and who should provide it. We could even talk about a distinction between welfare as charity and welfare as the services that the laboring classes were entitled to as part of their remuneration. Since both forms of welfare have an impact on living standards, both will be discussed in this section.

TABLE 1

Chronology of main events and relevant presidencies, 1855–1952

It is also important to take into consideration the role that politics played in welfare provision. During this period, politics defined the role the state would play as welfare provider and to what extent the state was going to allow or even encourage the participation of the Church and civil society in this part of the nation’s life. Welfare institutions and welfare provision would be affected by the conflictive relationship between the state and the Catholic Church from the promulgation of the Reform Laws and the 1857 Constitution until the late 1930s, when a new equilibrium in Church–state relations was established and the state took a more proactive role in the provision of welfare.

Politics remained relevant after 1910, because the state’s participation in welfare provision initiatives was defined to benefit groups that the ruling party viewed as allies. These initiatives were the antecedents of poverty-alleviation programs that became ubiquitous after 1950. As we will see in this section, the betterment of the living standards of the population at large and the potential gains that this improvement could bring to Mexico as a nation were part of the political rhetoric; the reality, however, was one of persistent inequality.

The argument of this section is threefold. First, in Mexico the design of welfare institutions was shaped by social and political events taking place during this period as much as by ideas on welfare developing in countries of the Western world as understood by Mexican intellectuals.

Second, the role of the Catholic Church, the most important welfare institution since the colonial period, dramatically reduced its capabilities of serving the needy during the period 1850–1950. With the triumph of liberals and the drafting of a new constitution in 1857, the state managed to establish a legal framework that undermined the power and wealth of the Catholic Church such that it diminished the size and scope of its welfare institutions. Although some secular private welfare institutions emerged during the second half of the nineteenth century, they did not fill the void left by Catholic charitable enterprises as they ceased to exist. Secular welfare institutions barely grew in number and size during the first half of the twentieth century, in large part because the state bureaucracy hindered their creation and the government did not grant them legal personality until the late 1940s.1 In the postrevolutionary period, the limited growth of these institutions was also the result of the new centralizing and paternalistic state rhetoric that took responsibility for the people’s welfare. This discourse did not favor the development of a sense of social responsibility among the upper strata of the population to inspire them to “give back,” in the way it evolved in other countries of the Western world.

The third part of the argument of this section is that in Mexico, the foundations of a welfare state did not begin to take a clear shape until the late 1930s, during the Lázaro Cárdenas presidency. During the second half of the nineteenth century, politicians and intellectuals reflected extensively on the role that the state should play as a welfare provider and continued to support the idea that it was not the responsibility of the state to care for the poor. There were a few laws and policies developed around that time that had some impact on welfare. Still, the incentive behind their creation usually had to do with the need to meet the requirements of economic modernization. In the early years of the postrevolutionary era there were some glimpses of intent to establish a legal and institutional framework that could help improve the well-being of the population; after all, in the consolidation of the new revolutionary state it was important to gain the support of groups that could serve as political allies. These glimpses can be seen in the reforms made to the 1917 Constitution pertaining to labor rights. Nonetheless, the actual enforcement of the new legislation was very slow and tended to favor only a limited segment of the population, namely, those groups that the government needed as allies to guarantee political stability and, after 1929, to guarantee permanence of the ruling political party in power.

The following section is organized into three chapters. The first chapter presents the different philosophical, political, and economic ideas that informed and influenced decision makers in Mexico on the subject of welfare. This chapter will overview debates on how the poor should be considered an undeniable part of society, if they should or should not receive any form of help, and, if so, who should be responsible for providing such assistance, the state or civil society. This chapter will also examine the different discussions around the social question that stemmed from changes in patron–client relations as a by-product of the transformation in productive processes and the rise of capitalist modes of production. In general, Mexicans emulated the Western world model, but the different countries of this group each had its own way of addressing the different aspects of welfare provision; Mexicans did not follow the example of one particular country. Instead, they borrowed ideas from different countries that they deemed feasible to adopt in Mexico, then designed and implemented their welfare institutions à la mexicaine.

The second chapter will present an overview of the evolution of charitable institutions during this time period, but will also provide a brief background on the colonial era. The purpose of this chapter is to explain how the Catholic Church went from having a monopoly in the provision of welfare through different entities such as convents, hospitals, schools for the poor, and hospices, in close collaboration with civil society at large, to being gradually dispossessed of its wealth and attributions. We will explain how the Church continued to assist those in need, even under the persecution of the state, and how new nonreligious charitable institutions emerged despite the legal and bureaucratic obstacles posed by the government.

The third chapter will cover the evolution of welfare as a public policy. For most of the nineteenth century there was recognition from a good number of people in power that there was widespread poverty, but there was no direct commitment to alleviate it. Instead, they sought to modernize the nation and to foster economic growth, assuming that as a result there would be fewer poor people. Although governments at times took concrete actions to rid society of social problems that poverty provoked, such as vagrancy in the cities, the results were not necessarily successful over the long run, since they did not address the root causes. I will also explain how changes in the modes of production as a by-product of the rise of capitalism required a revision in patron–client relations. In this chapter I will show how at the end of the Porfiriato, attempts to modernize the organization and operation of the government brought changes in the institutions that provided some form of welfare assistance. A distinction emerged between welfare assistance to the poor and welfare as a means to enhance social development. In addition, by the late 1930s the postrevolutionary government made a commitment to care for those in need. Institutional changes to establish a strong welfare state were promising, but the actual reach of the new institutions was disappointingly small.

![]()

Chapter 1

The Ideas Behind the Making of Welfare Institutions

The Catholic Church of the nineteenth century viewed poverty as inherent to human society and hence ineradicable. The biblical foundation of these assertions, rooted in the readings of Matthew 26:8–11, among other texts, gave the basis for accepting poverty in the Western world as well as for proclaiming the Catholic Church the mother of the poor and hence the institution responsible for assisting them. In general terms, this is how in the history of the Western world the terms Catholic Church, poverty, and charity became closely intertwined. In this chapter I will discuss the ideas that shaped concepts and policies on welfare, poverty, and charity as they evolved in the Western world and as they were adopted in Mexico.

Prior to the mid-nineteenth century it was, in fact, basically impossible to eliminate poverty from societies.1 This was because all societies during the preindustrial era—and even during the first phases of the Industrial Revolution—were still economies whose growth was bounded by physical restrictions inherent to traditional modes of production, especially in agriculture. Agriculture required that the greatest portion of laboring people made use of extant production techniques; the constant threat of potentially adverse climatic conditions such as droughts or frosts made societies vulnerable to crop failures, and these failures forced people into poverty.

Three classical economists of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries described and explained these limitations: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and Thomas Malthus. Although Smith and Ricardo had a great optimism about the benefits of industrialization, they recognized the limits imposed on economic growth by agricultural production. In his Wealth of Nations (1776), Adam Smith declares his enthusiasm for the effectiveness of the division of labor. In his famous parable of the production of nails, he explains the gains to be made from this innovation in the organization of production. Still, he recognizes that the division of labor as introduced in industrial production could not be applied in agriculture.2 In the early nineteenth century, David Ricardo, in his On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation, presents the different angles of diminishing marginal returns (DMRs), which offers an additional explanation of the limits of agriculture production to the one posed by Smith.3 Ricardo assumes a fixed method of agricultural production, such that the condition of the land becomes the key variable in value.4 Ricardo explains that DMRs were among the causes that inhibited the further growth of economies at the time, and that DMRs also held true not only for food production, but for all sectors of the economy. He reasons that nearly all branches of production were based mainly on animal and vegetable raw materials that were a part of agriculture. Thomas Malthus’s argument of human demographic behavior (ca. 1803) was another compelling explanation, contending that traditional societies would always have poor people.5 In times of plenty, better nutrition would decrease mortality and, lustful as human beings were, they would raise fertility rates and eventually the additional labor supply would force wages back to the minimum subsistence level.

Decades later, the ideas of these three classical economists were put into question by technological innovations in agricultural production that would free economies from such barriers. The introduction of these innovations increased the production of agricultural goods while it required fewer people working in the fields. Fewer people working in the fields meant more people available to work in other sectors of the economy, such as the nascent industries. These changes resulted in a steady rise in real incomes for the economy in general. More wealth was created. Changes in the productivity of the economy resulted from innovations in agricultural technology and industrialization as much as from research and innovations in the fields of physics, chemistry, and biology that made it possible to develop technologies that increased the supply of energy available for production.6 In addition, despite the growing prosperity in the economy, fertility tended to decline in most Western societies. Alas, Malthus did not live long enough to see that the evolution of populations in the industrializing world did not match his argument on human demographic behavior.

Karl Marx was one of the contemporary observers of the mid-nineteenth century who realized that the new modes of production created more wealth, and he understood the depth of transformation that the rise of capitalism would bring to Western economies. Marx feared that, in the new capitalist economy, workers would not receive a fair remuneration for their labor and the poor would not have any part in the distribution of the new wealth created.7 He noted that the scale of economic growth taking place in the mid-nineteenth century was such that enough wealth was being created to eliminate poverty. From that time on, if poverty existed, it was no longer the fault of weather calamities producing poor harvests or lack of land to put to work, but rather a lack of political will to provide the lower strata of the population with sufficient remuneration from labor to acquire adequate food, fuel, housing, and clothing. Malthus, in other words, had been refuted by the capitalist mode of production. Thus, Marx insisted, if poverty existed in an industrialized society, it was because of the unequal distribution of wealth. From this point onward, industrializing economies had the potential to create sufficient resources from growth, and, for the first time in the history of humankind, the abolition of poverty was a possibility. Henceforth, Western societies had to modify their ideas on poverty. New modes of production also required a modification of labor relations as a rising number of people began to depend solely on their wages to earn their living.

It is important to define what we understand by the word poor as well as by the concept of poverty, both of which took on different meanings in the century this study examines. People could be poor in a definitive way, such as the elderly who had no one to care for them, those with incurable diseases, those with a physical or mental disability, or those who were so malnourished that they did not have the energy to work and make a living. Others could be poor due to unfortunate circumstances that could be described as temporary, for instance, those who were out of work or lost their crops and thus were not able to feed themselves and their families. The poor could also be pregnant single mothers or widows who had no one to look after them, or orphan children. These poor people were also defined as the able-bodied. Some poor people were lifetime urban dwellers; others were rural dwellers who in times of harsh conditions in the countryside migrated to the cities in search of work. Some scholars have drawn a distinction between those who are poor and those who are marginalized.8 The argument for this distinction is that poor people have an income, albeit insufficient to make a living; they are inserted in the economy. The marginalized are individuals alienated from the economy. Just as there were different reasons why someone could fall into poverty, it is reasonable to assert that each type of poverty requires different kinds of assistance. The Catholic Church decided its duty was to help both the poor and the marginalized according to the needs of each group. For the poor it was help to endure their condition (illness, old age), normally by giving them room and board. To the marginalized, it was helping them acquire skills that would integrate them into society as productive people. The definitions just described can be generalized to any preindustrial society or any society in the process of industrialization. What cannot be generalized is the way each society reacted to this phenomenon.

When trying to determine who is poor, we should also keep in mind that although some of the basic definitions of poverty are universal, poverty is very much ...