![]()

1

Writing the Periphery

COLONIAL NARRATIVES OF MOROCCAN JEWISH HINTERLANDS

Global Links and Jewish Disguises

As a columnist and foreign correspondent working in the early twentieth century, Pierre van Paassen, a Dutch-American writer, worked for a number of newspapers, including the Toronto Globe, the Atlanta Journal Constitution, the New York Evening World, and the Toronto Star. He became one of the best-selling and most influential authors of his time. In addition to reporting on colonial issues in North Africa, including the slave trade, van Paassen investigated Middle Eastern issues and interviewed many key political figures in the region including the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem, Hajj Muhammad Amin al-Husayni (1895–1974) in 1929.1 In 1933, accompanied by a British intelligence officer, van Paassen visited the Dome of the Rock disguised as an Arab hajj (pilgrim) to gather information during the Friday sermon about local views regarding the British Mandate and Muslim attitudes toward Jewish migration to Palestine.2 Despite his wide-ranging activities as a journalist and writer, van Paassen gained fame for his reports on the relationship between Arabs and Jews within the British and French Middle Eastern colonies.

As a world-famous Unitarian Christian reporter, van Paassen was an ardent supporter of Zionism and a lobbyist mainly in the United States for the establishment of a Jewish state.3 He accused the League of Nations and Britain—in particular—of betraying the Jewish People, especially after what befell European Jews in the Holocaust. Van Paassen prefaced The Forgotten Ally with a critique of the British Colonial Office in the Near East, highlighting Europe’s failure to protect Jews and secure a country for the Jewish People in Palestine. Van Paassen stated that “as one who is aware and who feels with a sense of personal involvement Christianity’s guilt in the Jewish people’s woes and the constant deepening of their anguish, I could no longer be silent.”4 His political zeal for a Jewish state became reflected not only in his call for supporting European Jewries in the aftermath of the Holocaust, but also in facilitating Jewish aliya (immigration to Eretz-Israel) worldwide, even among the Jews of Africa.

On November 7, 1928, as the Paris-based foreign correspondent for the New York Evening World, van Paassen wrote an article about what he deemed a small and remote Jewish community in the heart of the African desert:

Hostile tribes, disease, hunger, poverty and other vicissitudes had interfered with the ancestral project of reaching the Promised Land, and they had remained in the desert. But the Jews . . . never had abandoned hope altogether of continuing their interrupted migration some day and of ultimately residing in the land that “that flows with milk and honey.”5

This passage was written about the Jewish society of Akka—the main ethnographic site of this book. Van Paassen based his story on an interview with René Leblond, whom he presumed to be the French consul of Akka, and who had descended on the outskirts of the Jewish settlement when his plane developed an engine problem and was forced to land. Leblond was collecting geographic and cartographic data for the colonial mapping of the southern Moroccan territories that the French military had yet to control. By 1928, Sémach, a Bulgarian teacher of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (AIU) in Iraq and Morocco, questioned the truthfulness of the story, alleging that there was no French consul at Akka and that Leblond did not show up in the registers of the French Foreign Ministry.6 Yet, van Paassen’s story about the presence of “a flourishing and tranquil Jewish community, numbering several thousand souls, in the heart of the African desert, surrounded on all sides by savage and semi-civilized Moor and Berber tribes,”7 has become part of an authoritative and institutionalized historiographical narrative about the Jews of Akka in particular and Saharan Jewries in general, despite its unsubstantiated sources.8

Apart from a few notes about the history and culture of the small Jewish community of Akka, van Paassen simply skipped over many historical dates and events without providing detailed information. He noted that the last European visitor the Jews of Akka had seen was “an explorer in 1866” and that “since that day no traveler from Europe had been in their midst.”9 Contrary to this claim, the French traveler Charles de Foucauld visited Akka around 1882 with his guide, Mardochée Aby Serour, himself a native Jew from Akka.10 I do not question here van Paassen’s sources; Leblond, if such a name existed, could have been told of these events by the Jewish elders of Akka he claimed to have interviewed. The inaccuracy of these dates and the vagueness of events reflect the dilemma of reliability in oral sources that faced European travelers and later scholars of rural Jewish societies throughout the Middle East in general and Morocco in particular.11

As rural and Saharan Jews were “discovered” by European travelers and are now studied by Moroccan historians and anthropologists,12 how should these historical and ethnographic accounts be assessed and analyzed? What are the biases and agendas of colonial and post-colonial narratives that frame the historical discourse about Saharan Jewries in particular and Middle Eastern Jews in general? What is the role of post-colonial national researchers in the rewriting of these rural marginal communities? If we use a combination of European travelers’ accounts and local oral testimonies, how should we understand these sources despite their purported contradictions and likely inaccuracies?

In this chapter I grapple with these questions and reflect on the connections, silence, and amnesic gaps between the colonial and post-colonial historical narratives, as I wade through European travelers’ accounts, post-colonial nationalist histories, Moroccan literature about Jews, and my own ethnographic experience as a native Moroccan Muslim anthropologist studying the Jews of my hometown and region. Through the chapter we will meet pro-Zionist Christians and Muslims, and deeply anti-Semitic government officials and colonial administrators, and learn the stories of alliance and betrayal in the common lives of my ethnographic subjects and their parallels in historical figures. The common practice of disguising oneself as a traveling Jew not only links the stories of van Paassen and the colonial administrator de Foucauld, but returns in my own ethnographic experience, as I become the object of a similar rumor while in the field. Before I discuss these issues, I begin with a short ethnographic narrative that contextualizes the Jewish community of Akka in the wider region of southeastern Morocco.

Jewish Society in Saharan Hinterlands

When I arrived in Akka in February 2004, I walked through the Jewish shops outside the mellah (Jewish neighborhood) not far from where the market of Tagadirt took place. I could not access any of the tiny shops lining the mellah’s entrance. It was obvious that these shops had not been open for business since the last time Jews left for Israel in 1962. A suq (market) without Jews, as the Moroccan proverb goes, is like bread without salt. “When the Jews settled outside Morocco,” Ali, a ninety-year-old consultant, noted, “the market lost its salt.” Masses of thickened red dirt collected around the shops’ entrances leaving their small wooden doors to the mercy of termites. Between the late 1820s and 1880s, a number of European travelers such as Davidson and de Foucauld13 described the markets of Sus region and the Anti-Atlas as central trading and resting posts in the western sub-Saharan trading routes. When I visited these once busy markets in the Saharan fringes, the Moroccan adage made sense to me, especially when Ali, my guide, stopped in the middle of the square where the weekly suq was once held and said:

Look around you, the only thing left of Jews today is their deserted and decaying buildings; their shops are closed. Their houses are mostly unoccupied. The only reminder of their presence is their cemeteries. Their tombs remind us of a Jewish time and place. It is as if Tagadirt is a factory that closed, leaving thousands unemployed and without salaries. I wish Jews had never left. They added yeast to this economy.

According to Ali, without Jews, local markets could not grow or prosper. Hence, when Jews left for Israel, Akka as well as other rural and urban communities throughout Morocco suffered from the absence of the “salt” they had added to the local and regional economies. Ali’s remark echoed many statements I heard from other members of his generation of great-grandparents, whose narratives and memories were replete with nostalgic moments about a Jewish time and place that was.

In the nineteenth century, Marrakesh, Essaouira, and to an extent Tarudant and Agadir, were major urban epicenters of the Saharan economy.14 Jewish peddlers and merchants throughout the southern regions of Morocco exchanged their commercial articles as they traveled between these epicenters and chains of satellite rural communities throughout southern Morocco.15 Southern Morocco includes the Anti-Atlas, the Noun (region along the Atlantic Ocean), Oued Sus Valley, the southern slopes of the High Atlas, and southern Draa Valley, all stretched out before one can enter the Saharan interior. Throughout the Sus region, Jews lived among Berber and Arab communities; Jewish families resided in this area until their final exodus to Israel in 1962.

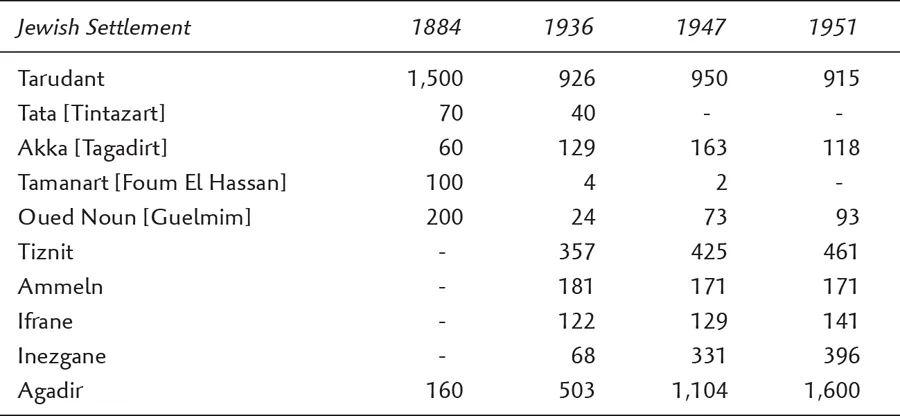

Early legends claim that these Jewish communities are some of the oldest in North Africa. The Jewish kingdoms of Ifrane (Oufran) and the Draa Valley date back to the pre-Islamic period.16 The trading centers of Essaouira (Mogador), Agadir, and Tarudant had always been regarded as the urban capitals of the Jews of Sus, although Marrakesh was also a major urban destination of Jewish students and traders (Table 1).

In the southern Saharan hamlets, Jews lived among Muslim communities under the protection of tribal lords. As the French succeeded in their gradual pacification of the south, completed by 1933, a few Jews applied for French protégé-status for fear of losing local tribal support. The Jewish communities of the bled (hinterland) continued to fall under the protection of tribal lords and local individuals.17 The French administrators left the political and economic management of the south in the hands of tribal qaids, known as the lords of the Atlas, specifically Si Abdelmalek M’Tougi, Si Taieb Goundafi, and Thami Glaoui.18 The use of the tribal qaids was for the subjugation of the tribal dissidents. Therefore, Marshal Hubert Lyautey, the first resident-general in Morocco (1912–1925), and his followers opted for a policy of indirect rule in the lands under the management of these lords, deferring to local qaids on issues relating to local Jews. In Teluet, a village under the control of Thami Glaoui, Slouschz reported that the chieftain of Teluet would imprison members (including Jews) of tribes he had conflict with when they attempted to travel to Marrakesh for business until his feuds with the tribes were resolved. Slouschz claimed that during his travel through Teluet, “there were ten Jewish merchants from Askura who had been imprisoned because their Mussulman patrons had refused to recognize the authority of the Kaid of Teluet.”19

Table 1 Jewish population in some areas of Sus, 1884–1951

Throughout southern Morocco, Jews were caught in these political changes, remaining indispensable economic agents as well as marginal political players in the social structures of these rural communities.20 The traditional rural economy was reliant on Jewish peddlers and artisans,21 who provided important services to the local agrarian Muslim society. As peddlers, metalworkers, and saddlemakers, the Jews of Akka and other communities throughout the Anti-Atlas played an active role in tribal economy, which depended on them as mediators between the city and remote rural settlements.22 In return for these valuable services, Jews were guaranteed the protection of local Muslims—though guarantees were sometimes jeopardized by feuds between neighboring tribes.

Akka became an important satellite community in the trans-Saharan commercial chains in the nineteenth century.23 It housed one of the most important Jewish communities at the fringes of the Moroccan Sahara. Akka is a green valley of palm groves at the mouth of Oued Akka, a tributary of the Draa River. It comprises the villages of Irahalan, Rahala, ayt-‘Antar, Tagadirt, Taourirt, Agadir Ouzrou, Qabbaba, and al-Qasba. An abundance of water (ten water sources) has made it one of the major settlements of the Anti-Atlas that survive on intensive subsistence agriculture.24 Situated about thirteen kilometers from the ruins of the Islamic city of Tamdult,25 Akka emerged as an entrepôt in western Saharan trade following the fall of Tamdult in the fourteenth century. During the nineteenth century, Akka and Tata (Tintazart) became among the most prosperous centers of the Moroccan south. According to de Foucauld, Akka was one of the principal resting posts of the caravans toward Essaouira.26 Gold, slaves, leather, and fabric brought from the Sudan were traded in its markets.27

Jewish communities were largely concentrated in urban conglomerations of the region of Sus, such as Agadir, Tiznit, and Tarudant, as well as pre-Saharan remote settlements like Aguerd (Tamanart), Tahala, Tintazart, and Ouijjane. As part of a colonial census of the Jewish population of Sus in 1936, Capitaine de La Porte des Vaux argued that the Jewish population of Sus underwent major transformations because of massive local and regional movements since de Foucauld’s Reconnaissance au Maroc in 1888.28 De La Porte des Vaux asserted that major economic changes during the nineteenth century at the level of maritime trade, in addition to ...