![]()

One

Mapping Ottoman Music-Making

Necdet Yaşar (b. 1930), Turkish classical musician and renowned master of the tanbur (long-necked lute), came to the United States from Istanbul in the early 1970s to teach in the ethnomusicology program at the University of Washington in Seattle. There he met the late Reverend Samuel Benaroya, who was born and raised in Ottoman Edirne in the early twentieth century, emigrated to Seattle through Switzerland in 1952, and was serving as hazan (prayer leader, or cantor) at one of the two Sephardic synagogues in the city. Thirty-four years after their first meeting in Seattle, Necdet Yaşar sits at his print shop in the central neighborhood of Unkapanı in Istanbul, and remembers first meeting Benaroya:

He came to the university and introduced himself. . . . Later I saw him beat a long usul [rhythm pattern]. He beat devir kebir. I was surprised. He beat long usuls on his knees, Ottoman-style, meşk usuls,1 and he recited a piece for me. He really surprised me. He beat usuls incredibly well. . . .

He knew [the old makams, or musical modes]. For example, when I gave my class at the University of Washington, he came to watch. . . . I was teaching Rast makam to the students; rather, makams from that family. I was explaining makams that were like Rast. I’d say this is Rehavi, the difference is so and so, this is Sazkar, this is Suzidil Ara. He knew the Rast family, that is, the whole family of makams. He was a good musician, an excellent musician. . . .

[He said] while in Tekirdağ [sic] he learned classical Turkish music—long usuls, makams—but I have no idea whom he learned from. Maybe a teacher lived in Istanbul. Maybe he learned in Istanbul and went back to Tekirdağ [sic] from there, I don’t know.2

Necdet Yaşar goes on to describe how “Ottoman culture has a language. It has a particular old language” that Benaroya also knew. “There are a lot of fine musicians, a lot of talented instrumentalists. But they use only the new language, they use today’s language.” Using the linguistic analogy of the Turkish word “to go,” he explains that in the past, speakers drew from a colorful palate of vocabulary with shades of meaning, such as to go hurriedly, to go and reach a destination, to go by car, train or ferry, to set off early:

To describe something there are five, six, seven, maybe eight different words, ten words. This is the richness of a language, but a person could describe their emotions with one word. They could describe them, but the richness would be lost. . . .

Music is the same. . . . In the musical and makam system, as well as in improvisation, there is such a thing. There is the same richness. . . .

[Benaroya and I] spoke the same language. He loved me and I also loved him. I respected him highly, and he also highly respected me.3

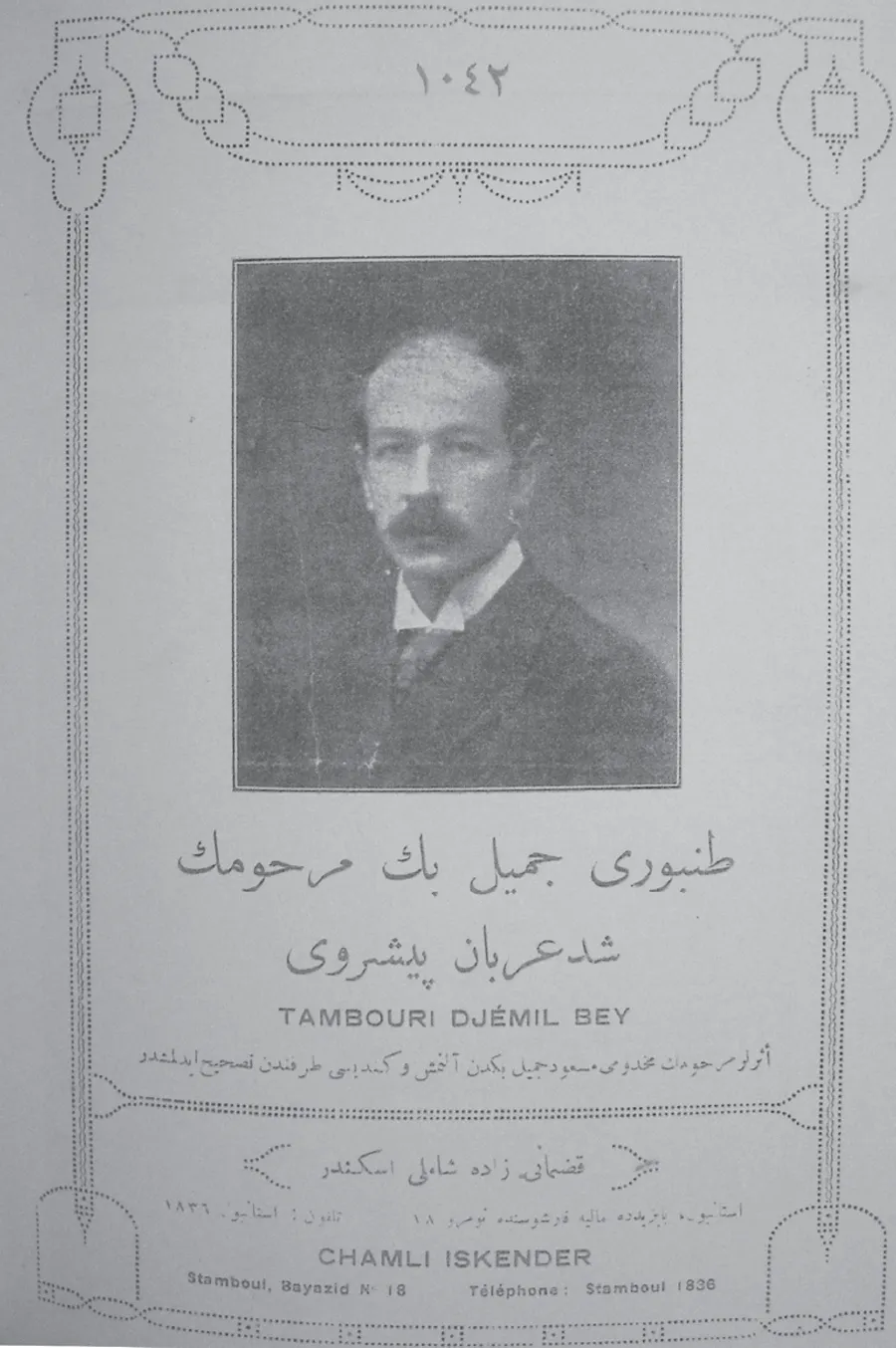

According to Necdet Yaşar, he and Benaroya shared an Ottoman musical language, even though Necdet was twenty-two years his junior, was separated for years by geographical distance, and had grown up musically among the Turkish Muslim majority of Istanbul rather than within a provincial minority. Strikingly, based on the memories of Benaroya’s daughter, Benaroya recalled Necdet with high esteem throughout the years since their first meeting, conveying an intimacy unfamiliar to her in his other relationships.4 It may not be surprising that two musicians growing up in the same home country (Turkey) and meeting abroad (Seattle) would be drawn to each other. We can also effectively bridge their musical age gap by placing both musicians within the same late Ottoman musical aesthetics: a student of Mes’ud Cemil in the 1950s, Necdet nonetheless considers the father, tanbur player and composer Tanburi Cemil Bey (1871–1916), his “spiritual teacher,” as he assiduously listened to, and strove to understand, his innovative style in his youth from recordings of the early twentieth century.5 Tanburi Cemil Bey was also among the most popular instrumentalists performing and recording at the time of Benaroya’s youth in Edirne.

Even if trained, figuratively speaking, in the same musical period, Necdet Yaşar, Samuel Benaroya, and their relationship raise questions that bear closer examination: how did two musicians, separated by community, mother tongue, and city of origin, share the same musical language? Whereas Necdet gave public concerts of classical Turkish music, locally and internationally, on the tanbur, Benaroya sang only in Hebrew for Jewish religious services in synagogues in Edirne, Geneva, and Seattle. As Necdet Yaşar himself asks, how exactly did a young Jewish man like Benaroya, growing up in a provincial city at a distance from the imperial center of the arts and performing exclusively in the synagogue, learn a broader Ottoman musical theory, complete with specialized terminology, at the advanced and comprehensive level that Necdet observed? Indeed, Necdet Yaşar, recognized in Turkey today as a living master of historical Ottoman makams, musical aesthetics, and the tanbur, is unquestionably a highly credentialed judge of Benaroya’s high-level musical skills.

Tanburi Cemil Bey on the cover of the musical score of his composition “Şedd-i Araban Peşrevi.” According to the text, the composition was taken from and corrected by his son Mes’ud Cemil and was published after his death by Chamlı Iskender (Tr, Şamlı İskender, a music publisher in Istanbul circa 1910–1950). Reproduced by permission from the collection of Mehmet Güntekin.

It is common knowledge among ethnomusicologists today that, based on the musicological evidence, Ottoman court music forms interpenetrated the religious services of non-Muslim Ottoman houses of worship—Jewish synagogues, and Armenian and Greek Orthodox churches. Moreover, a measure of published archival evidence testifies to interreligious contact and palace employment, suggesting pathways of cross-cultural flows. A number of sources, centuries apart, related to Ottoman Hebrew religious singing, confirm reciprocal meetings between Jewish and Mevlevi (“whirling dervish”) musicians.6 Recordings and publications about Jewish, Greek, and Armenian musicians reveal musical lives lived as musicians and composers at the court as well as cantors and religious leaders in their own synagogues or churches.7 One term for such individuals is haham-bestekar (haham-composer), alluding to the Jewish and wider realms that such composers sometimes worked within.8

Drawing on the rich Ottoman-Jewish musical scholarship of the past, we can enrich our understanding of Necdet Yaşar and Samuel Benaroya’s shared musicality by investigating Ottoman music-making through the prism of the historical urban landscape of the music and its practitioners. Among Istanbul’s streets and structures are the precise places, people, and activities involved in artistic cross-fertilization in the late Ottoman period. In the city, well-documented but isolated evidence of musical encounters enlarges into patterns of urban circulations, making visible and detailing our commonplace but under-articulated knowledge of multiethnicity in Ottoman music. Moreover, by tracing both structural and demographic changes in the urban landscape of Istanbul, we can track the migrations of music and its makers generally, and specifically among Ottoman and Turkish Jewry, to elucidate both the ruptures and continuities, however altered, in multiethnic music-making in a postimperial, nation-building era. Through bringing together discipline-specific source material—the ethnomusicological with urban and migration studies—we can “urbanize” the music-making under consideration and “musicalize” the urban landscape across a period of intense social change.

Questions arising from the particular musical friendship of Yaşar and Benaroya in the late twentieth century motivate this investigation into the details of Ottoman musical history in order to conceptualize the social ethos, economy, and urban configuration—and reconfiguration—of their world. How were artistic and social relationships cultivated between local Jews and musicians of other ethno-linguistic communities in the late empire? By extension, how did the well-documented musicological linkages between the respective repertoires develop within these diverse communities? What stories does the changing urban landscape of Istanbul have to tell us about distinctive residential soundscapes, patterns of music-making, Jewish practitioners and their migrations within and out of the city across the twentieth and twenty-first centuries?

Focusing on music as a social, collective process, rather than a series of artistic products, we will follow a selection of understudied Jews working as composers, commercial performers, religious leaders, and hazanim as they circulated in a variety of inclusive urban spaces, some composing or performing exclusively for their own communities, others participating in both Ottoman synagogue and court music, including its popularized forms. The life stories of such late Ottoman Jewish musicians—some of whom were religious leaders—who composed court music forms, be they instrumentals, or Hebrew and Ottoman-Turkish song, provide valuable evidence from daily life in Ottoman cities to delineate how court music circulated among Jews and their synagogues, and the ways in which Jews circulated among the music of the court. By analyzing Jewish biographical data in terms of how musicians moved within urban space, individual life details cohere into a fuller understanding of interactive urban music-making based in common patterns of musical activity, such as patronage, professional specialization, and apprenticeship. As we encounter distinctive examples of performing, composing, and teaching, we will contextualize particular activities in wider Ottoman music practices, to specify the contemporaneous nature of Jewish musical involvement. A focus on patterns of transmission will illuminate the pathways of the musical interactivity around such repertoires as the Maftirim. As a whole, the individuality of the biographies takes us beneath the surface of a seemingly amorphous imperial cosmopolitanism as the apparent source of cultural confluences, expanding on evidence from previous periods toward an understanding of the late Ottoman era. Our musicians’ shifting patterns of residency, moreover, together with the changing musical cityscape of Istanbul will lay the foundation for investigating the upheavals and survivals in their musical culture across the Turkish Republic.

A vibrant Ottoman studies scholarship is enriching our understanding of the empire’s social complexities in different locales at different historical junctures. Several studies spanning the empire, from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries, challenge past assumptions of ethnic divisions of labor and residence, suggesting groupings that include and cut across ethno-religious communities, such as networks of migrants, shopkeepers, workers, and café-goers.9 From the outset the Ottoman court employed teachers, performers, composers, and theoreticians from a wide swath of the population, cultivating musical forms held in common and an Ottoman artistic identity at times separate from or opposing one’s religious community.10 To the growing body of intercommunal research this chapter contributes a case study of late Ottoman musicians and their quotidian encounters, activities, and relationships within and beyond the palace.

This is not to say that the musical world or other social and economic relationships were without ethnic tension, conflict, or even violence in the course of the empire’s history. Those making music moved within multiple other worlds as well, and were thus affected by wider sociopolitical currents beyond their particular artistic milieu. As we shall see in Chapter Two, in times of social and political crisis, such as the violent shift from empire to nation, a musician’s affiliation with the Jewish community became increasingly significant to his social experience and life choices. As we follow Jewish composers interacting in shared urban spaces among diverse personages, then, we will see that these same musicians lived amidst distinctively Jewish spaces as well, and their lives, in the end, were shaped by their status as Jews as much as by their multireligious artistic relationships. It required specific musical, personal, and political advantages, as the following pages will show, to succeed as a Jewish musician in the Turkish Republic.

Musicians Circulating in the City

The life stories of four late Ottoman Jewish musicians—Hayim Moşe Becerano, Samuel Benaroya, Nesim Sevilya, and Mısırlı İbrahim Efendi—provide clues about the musical activity and urban ambulations that constituted interreligious music-making in the late Ottoman period. Two of these musicians composed or performed solely for liturgical settings (Becerano and Benaroya), whereas the other two composed a largely nonreligious repertoire (Sevilya and Mısırlı İbrahim Efendi). Three of them were religious functionaries at various levels (Becerano, Benaroya, and Sevilya), and one (Mısırlı İbrahim Efendi) worked only in the “secular” music marketplace (piyasa) outside the synagogue.11 All four musicians, nonetheless, moved among urban spaces, both far-reaching and more closely communal, that facilitated musical flows between their religious communities and the Ottoman public sphere as a whole. On the one hand, individuals performing both musical and religious roles, such as Hah...