![]()

1

Guilds and Elites in the Face of Domestic and Foreign Challenges

For Western visitors to late nineteenth-century China, one striking discovery was that “the people crystallize into associations; in the town and in the country, in buying and selling, in studies, in fights, and in politics.”1 Foreign intrusion from the mid-nineteenth century reinforced the Chinese tendency to act as social groups for self-defense, while the influence of social Darwinism also galvanized late Qing elites to organize themselves for national survival and revival.2 Thus, in addition to the traditional clans, guilds, charitable institutions, secret societies, and so on, anti-Qing revolutionary organizations began to appear from 1894, and reformist associations such as study societies also experienced ephemeral development before the failure of the 1898 Reform.3 Among these organizations, merchant guilds were the direct predecessors of Chinese chambers of commerce, which also displayed strong foreign influence.

However, the Lower Yangzi chambers of commerce were neither the natural results of guild evolution nor simple imitations of their Western counterparts. Like the late Qing reformist and revolutionary organizations, these chambers represented the collective responses of social elites, especially guild leaders and other elite merchants, to domestic and foreign challenges. Therefore, the rise of such elite merchant leadership in the guilds preconditioned the development of chambers of commerce. It also reflected relational changes more important than organizational evolution from guilds into chambers.

Chinese guilds have usually been divided by previous studies into regional guilds of merchants from the same native places and occupational guilds of people within specific trades. Actually, the guilds in late Qing China developed along both regional and occupational principles, as is shown by Goodman’s research on native-place associations and other merchant organizations in Shanghai. Nevertheless, these merchant guilds are still treated roughly as native-place or common-trade associations in my study simply because they emphasized one or the other of the two organizational principles in their titles, memberships, functions, and so on.4 Such merchant guilds could develop because of informal patronage rather than legal guarantee from local governments, and their elite leaders were crucial in helping them acquire such patronage from local officials.5

In order to develop, defend, and dominate such merchant groups under business competition, governmental intervention, social unrest, and foreign economic intrusion, guild leaders in the Lower Yangzi region made constant efforts to expand and intensify their regional, occupational, and official connections. As a result, they promoted guild development and also turned their personal and familial dominance into formal elite leadership. In the face of domestic and foreign challenges from the mid-nineteenth century onward, these guild leaders expanded their associational activities from business into community affairs such as charities, because of their concern not only for market and social crises but also personal wealth and power. Such elite merchants also joined radical reformers in response to the challenge from Western chambers of commerce in treaty ports, and they planned similar Chinese organizations with the double purpose of strengthening their socioeconomic dominance and saving Chinese business and the nation. However, their plans also included designs for widespread chamber networks, a matrix of the future relational revolution.

The Growth of Guilds and Elite Merchant Leadership: The Shanghai Case

The guilds in late imperial China included urban organizations with various titles, such as huiguan (meeting hall) and gongsuo (public office). The Lower Yangzi region nurtured some of the earliest merchant guilds in late imperial China, and it was also one of the few regions with large numbers of guilds by the late Qing period.6 Although this study argues against the assumption that these guilds directly federated themselves into chambers of commerce, their organizational development still provided an institutional foundation for the latter. In particular, the institutionalization and expansion of their elite merchant leadership and their interrelations directly prepared for the advent of the Shanghai CCA and successive Lower Yangzi chambers.

After huiguan began to appear as native-place clubhouses for officials in the imperial capital of Beijing from the 1420s, sojourning merchants and officials from the same native places also founded similarly titled organizations in Suzhou around the beginning of the seventeenth century.7 In this Lower Yangzi city, a gongsuo for silk weavers had probably existed as early as 1295, although merchants did not make wide use of this term for their associations until the mid-seventeenth century.8 The unique features of these Chinese guilds, especially their regional and official connections, contrasted sharply with those of their European counterparts. Thus, some scholars have tried to distinguish the common-trade gongsuo from native-place huiguan and deny the guild nature of the latter.9 Actually, these merchant organizations used the titles huiguan and gongsuo interchangeably and developed similar guild functions for self-protection, mutual assistance, and promotion of common interests.10 These guilds could perform such important functions because they used regional, occupational, and other socioeconomic ties to bond merchants together, and their leaders formed close relations with other social elites and officials.

In 1886, D. J. MacGowan, a missionary from the United States, had already noticed the close relations between guilds and officials in late Qing China: “Chief among edifices in mercantile emporiums are buildings erected by guilds for headquarters—places of meeting, theatrical representations, and as lodging-houses for high officials when traveling, and for scholars en route to metropolitan examinations.” He further divided the Chinese huiguan and gongsuo into merchant and craftsman guilds and likened them to chambers of commerce and trade unions in the West.11

MacGowan’s early work initiated the trend for Negishi Tadashi, Shirley S. Garrett, and other scholars to define late Qing chambers of commerce as guild federations under a Western signboard. Soda Saburo and Kurahashi Masanao also argue that these chambers resulted from the confederation of Chinese guilds against foreign aggression and from their need for business administration and social control.12 Yu Heping’s more recent work further emphasizes the tendency of the late Qing guilds to federate into chambers of commerce because they had gradually reduced regional and occupational exclusiveness under the influence of modern economic development.13

These previous studies have correctly indicated that merchant guilds laid an institutional foundation for chambers of commerce, but their analyses have oversimplified the relational changes among merchant organizations. Because social relations tended to become denser, stronger, and more intimate among merchants from a smaller area or a specific trade, regional and occupational guilds would naturally multiply and even subdivide into more localized and specialized organizations once they accumulated sufficient members and resources. In William T. Rowe’s study of late Qing Hankou, he indicates that regional and occupational guilds in this city gradually formed alliances because of the prolonged residence of nonnative merchants in this city and their need to cooperate with locals in trade and in the face of official and foreign interference. By contrast, late Qing guilds in the Lower Yangzi region rarely confederated along regional or occupational lines, and that was true even for Shanghai, the largest treaty port under direct imperialist dominance.14

Actually, the Lower Yangzi guilds in the late Qing period experienced continual multiplication and subdivision because their merchant participants increasingly formed regional and occupational ties at a more intimate level. However, they also developed interconnections through both interpersonal and institutional links in the face of domestic and foreign challenges. Moreover, elite merchants often held concurrent posts in various guilds because of their diverse business involvements and widespread social relations. They further formalized such guild leadership through their intermediary role between guilds and governments. It was through such relational changes that the Lower Yangzi guilds paved the way for the future chambers of commerce.

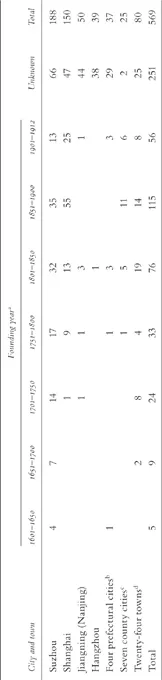

As Table 1 shows, the Lower Yangzi guilds began to appear around the beginning of the seventeenth century. They developed not only in Suzhou and Shanghai, the two successive centers of commerce in the region, but also in other provincial, prefectural, and county cities, as well as in market towns. Their number gradually increased from the year 1600 on because of long-term commercialization and urbanization in the Lower Yangzi region, but their numerical increase greatly accelerated after 1800. Because most guilds in this region were rebuilt or created after the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864) was suppressed, their development reflected mainly the associational activism of merchants, especially elite merchants, in the face of mounting social and national crises from then on.

These elite merchants used regional and occupational relations to create a large number of new guilds and also subdivided the existing guilds into more numerous organizations for more localized groups of merchants or more specialized trades. By creating and subdividing such organizations, they expanded their interrelated leadership in varied guilds and also intensified their communications with local governments concerning guild affairs. The relational changes among these Lower Yangzi guilds and their influence on future chambers of commerce can be clearly seen when one examines a case study of the dozens of merchant organizations that provided elite leaders for the Shanghai CCA and its successor, the Shanghai GCC.

TABLE 1

The development of guilds in Lower Yangzi cities and towns, 1601–1912

The major founder of the Shanghai CCA, Yan Xinhou, came from the Ningbo Guild (Siming gongsuo), which became a large and complex native-place association mainly through its organizational subdivision and relational expansion under interrelated elite merchant leadership. Around 1797, the Ningbo Guild appeared in Shanghai as a regional association at the prefectural level; it developed further through a fundraising campaign led by two of the Fang brothers. One of their nephews, Fang Chun, succeeded to the leadership and successfully petitioned Lan Weiwen, the Ningbo-born Shanghai magistrate, to exempt their guild properties from taxes. From the 1870s, new generations of upstarts from Ningbo, such as Yan Xinhou, got rich through quasi-official services and the management of family businesses and modern industries. They soon joined the Fangs and other established elite families in the leadership of this regional guild.15

By 1911, the Ningbo Guild had spawned one native-place association for merchants from Dinghai subprefecture, and forty-two occupational guilds or groups. These formal guilds and informal groups had more than 300 “major and minor directors” in 1901, and they all maintained personal and institutional links with the prefectural-level guild. Meanwhile, the Fangs and other wealthy Ningbo lineages in Shanghai gradually established their empires in businesses ranging from the sugar and silk trades to native banking and coastal shipping, and formalized their familial dominance in the Ningbo Guild. By 1836, these elite merchants had already developed a stable guild leadership composed of four directors (dongshi), including two of the Fangs; they also established the position of assistant director.16

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the Ningbo Guild was still under the leadership of four “annual directors” (sinian dongshi), including Yan and one of the Fangs. Under them, about a dozen monthly directors (siyue dongshi) were selected from the affiliated occupational groups for supervising business affairs, while two salaried managers (sishi) were appointed by these directors to handle general and accounting affairs.17 Although this guild experienced continuous subdivision after its emergence and did not even affiliate with the Shanghai CCA in 1902, such elite merchant leaders as Yan Xinhou still used their concurrent positions in occupational guilds, semiofficial enterprises, and so on to found and dominate the first Chinese chamber of commerce.18 Thus, the link between the Ningbo Guild and the Shanghai CCA reflects how the Lower Yangzi guilds led relational changes toward chambers of commerce through the development of formalized and interlocked elite merchant leadership rather than through the progressive confederation of their organizations.

In late Qing Shanghai, Cantonese people were rivals of thos...