![]()

One

Discovering the Nation Nathan Birnbaum and Early Viennese Jewish Nationalism, 1882–90

Nathan Nahum Birnbaum was born in Vienna on 16 May 1864 to Menachem Mendel Birnbaum and Miriam Birnbaum, née Seelenfreund. Preserved reverentially in thick photo albums in the Family Archive in Toronto are the faintest traces of the world of the families of Nathan and his wife, Rosa Korngut, all members of the same generation of immigrants. An 1868 photograph of Menachem Mendel shows a young man with close-cropped hair and the high-collared shirt, tie, vest, and jacket of a striving young Viennese merchant. Pasted on another page is a picture of Nathan’s father-in-law, Asher Zalke Korngut, a young, thin man in a rekl, a long, identifiably Jewish outer garment, and a dark skullcap. Together, the two pictures tell a story of the complex society into which Nathan was born. In the early 1860s, there would have been many Jews in Vienna that looked and dressed as both men did. Just over a decade after the revolutions and civil war of 1848–49 and the loosening of restrictions on Jewish settlement in Vienna, many had left the small towns and villages of the Austro-Hungarian Empire to seek their fortunes in its increasingly cosmopolitan urban centers. It is doubtful they would have attracted much notice, particularly in the heavily Jewish 2nd District, Leopoldstadt. Here they were two among many immigrants and strivers whose numbers swelled the Jewish population of the city for the last half of the nineteenth century until the end of the empire itself.

These photographs are commonplace, but in their banality they portray a defining journey that affected hundreds of thousands of Jews in nineteenth-century east-central Europe. For Menachem Mendel and Asher Zalke, at one end were the provincial towns of Galicia, the most economically depressed, ethnically divided, politically retrograde, and religiously traditional region in the empire. On the other was the cosmopolitan center of Vienna in the process of transformation from a sleepy and conservative capital to a center of the scientific, cultural, and political avant-garde. This movement was the defining transition in the lives of both men, definitively forming their exterior experience, the interior of which we know little.

Neither the fathers nor their children would negotiate this passage from the Galician provinces to Vienna easily. Menachem Mendel, his small family barely established in Vienna, died when Nathan was eleven. Nathan, who had been placed on the track of social ascendance for Jews of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the Leopoldstadt Gymnasium, portal to the Viennese university system, would spend most of his life repudiating that same society in ever more radical ways. When Menachem Mendel died, he left Nathan a small inheritance that a few years later the teenage university student would use to found the first Jewish nationalist newspaper in central Europe—a rejection of the path of bourgeois integration upon which he had been placed. It was an unconscious act of rebellion that would, decades later, lead Birnbaum back to an identity defined by an idealized version of the very place his father had left behind. The last images of Nathan Birnbaum show him, after a lifetime of intellectual travail and wandering, resembling both his father and father-in-law. In all later images we find him wearing a dark suit of modern European respectability and perched atop his stately, graying head, a broad black yarmulke, to him an explicit symbol of his rejection of this very modernism.

Menachem Mendel Birnbaum (Courtesy of Nathan and Solomon Birnbaum Family Archive)

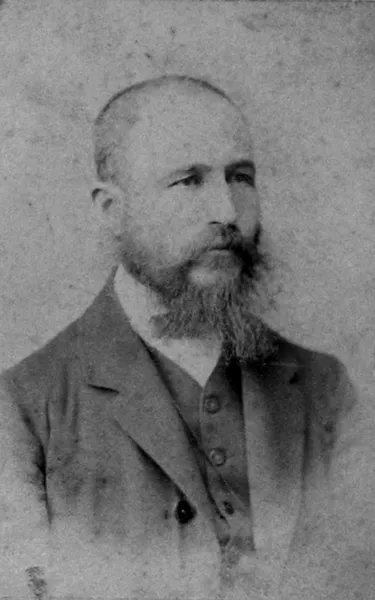

Asher Zalke Korngut (Courtesy of Nathan and Solomon Birnbaum Family Archive)

Nathan Birnbaum was a prolific writer, but little of his massive bibliography was devoted to contemplating his life, and even less his youth or family. The small trace of reflection we do find is an account published in a short autobiography for a 1924 celebratory volume in honor of his sixtieth birthday. It is the most detailed account of the lives of either of his parents. “My father, Menachem Mendel Birnbaum, may he rest in peace, was from Ropshitz (Galicia) and came on his mother’s side from a Hasidic family, close associates of the old Ropshitzer rebbe (his merit be upon us). He, however, was no Hasid; on the contrary, he was a bit of a maskil, but still very much a Jew.”1 Birnbaum’s sketch of his father was an idealization even in 1924: he was a young believer, from a family of some importance due to its proximity to the local Hasidic rebbe in the religious world of the traditional shtetl. Tied to the conservative world of his town, he was nonetheless enticed by the wide world advertised by the Haskalah, yet remained—“still very much a Jew.” Unlike the unfortunate author, this passage suggests, Menachem Mendel was rooted in a reality his son was unwittingly denied, with the result that, like many of his contemporaries, Nathan had to struggle to be “very much a Jew.” He writes of his mother in the same nostalgic vein. “My mother, Miriam (may she rest in peace), was born in Hungary, in a region that . . . today [1924] has been absorbed by Czechoslovakia [Carpathian Rus]. She was an orphan, and as a young girl of ten she came to Galicia to live with a brother who had settled there earlier as a religious judge [dayan] in Tarnow. There she married my father. She was the daughter of the Kashover Rav, Rabbi Shlomo Shmuel Seelenfreund, a grandson of the Shemen Rokeah, a sixth-generation descendant of the Shakh. . . . Her family was very mitnagdic.”2 While the facts of this account are no doubt true, Birnbaum’s emphasis on his mother’s lineage and her mitnagdic affinities highlight her authentic ties to the world of her ancestors—ties that Nathan himself felt he could not take for granted.3

But it is the narrative of his parents’ life, not their lineage, that is the most interesting element of Birnbaum’s account. Written later in life, after an epic intellectual journey, his words are a charged reimagining of the inner life of his parents. He uses terms that reflect an acute awareness of his audience’s sensibilities—maskil, mitnagdic. While Birnbaum’s father may well have had an interest in nonreligious intellectual pursuits—indeed, his choice to set his son on a German-Viennese (non-Jewish) educational track indicates as much, as certainly there were other options—it is unlikely that this was as defining a feature of his identity as Birnbaum suggests. Nor was the intellectual bearing of his mother’s family or his father’s familial association with the Ropshitz Hasidic dynasty likely as consciously central to his parents’ self-perception. But in 1924, in his new identity as “the Ba’al Teshuva,” as he is still reverentially remembered in some circles, this terminology was familiar and easily consumed by his Orthodox reading public. It held meaning disengaged from the historical but was very useful to him as he sought legitimacy in the eyes of the Orthodox world he had entered late in life.

The reality of Miriam and Menachem Mendel’s lives and aspirations was more prosaic than Birnbaum’s description. Their hometowns of Ropshitz and Tarnow, located about fifty miles apart, were two of dozens of small to midsize towns that dotted the countryside of Austrian Galicia, northeastern Hungary, and Bukovina, home to a combination of Jews, Poles, and Ukrainians, with Jews often the majority of the town population. Although changing in the nineteenth century like all of central Europe, these towns retained a significant residue of the traditional social makeup that had existed for centuries. Miriam was the daughter of a rabbinic and socially important family, raised by a brother who, as a rabbinic judge, was part of the institutional religious structure of the town. As an orphan she was dependent upon her brother’s resources and reputation to find her a match (arranged marriages, especially among rabbinic families, were not unusual). Interestingly, despite an illustrious rabbinic lineage, she does not marry into a rabbinic family but a small-scale mercantile one. This may tell us about Menachem Mendel: he received a traditional education and was intellectually curious (suggested by the term maskil Birnbaum uses); however, he was not a member of the rabbinic elite. Although we have no record, the match could as likely have been the product of personal choice as arrangement; but at the very least we may assume that Menachem Mendel was suitably a part of the traditional world (and thus no maskil in the sense it would come to be understood in the Orthodox world) to satisfy the bride’s family.4

The search for economic sustenance led Menachem Mendel and his bride to migrate from the Galician provinces to Vienna, probably around 1860, as did an increasing number of Jews from the region in the late nineteenth century. Nathan, born soon after, described his early life as succinctly as he does his parents: “My parents immigrated to Vienna, and I was born there on the tenth day of Iyar, 5624. I was given a Jewish and a German name: the Jewish name ‘Nachum’ after my father’s father, and the German ‘Nathan’ (a reference to the play Nathan the Wise by Lessing).”5

In spite of the synthesis his father may have hoped for in naming his son after Gotthold Lessing’s most famous literary character, Birnbaum recalls his alienation from Viennese Jewish culture beginning early. “I was educated in German schools. After four levels of elementary school, I went on to Gymnasium. There is no doubt that German culture had a profound impact on me. Only I was in no way disposed to consider myself a German despite the fact that one would be unable to find a single Jewish youth in Vienna who didn’t consider himself a German.”6 Such sophisticated ideas about cultural homelessness placed in the mind of a young boy by his sixty-year-old self may invite skepticism. He was, after all, one of many of his generation who went through the same process of acculturation at a young age; many, if not most, went on to identify deeply with Austrian-German culture and made it their own in a variety of ways.7 But clearly some aspect of his identity as a first-generation Viennese Jew unsettled Birnbaum deeply at an early age. He himself pinpoints the coalescence of his feelings to a revelation that occurred while he was an adolescent in Gymnasium: “I myself was uneasy when I saw Jews acting so completely German, without following the thought through any further for the time being. It was [only] in the fourth or fifth form of Gymnasium (1879 or 1880) that I was struck as though by lightning with a thought during a conversation with a friend, which I put this way: ‘Really, we should recognize ourselves as a Jewish nation, but of course that’s not possible.’”8 Written in 1933, these words reflect decades of involvement in Jewish nationalism and, like his earlier comments, should not necessarily be accepted uncritically. Yet the tension he describes, his feeling of unease with schoolmates he regarded as aping German culture and mannerisms, persisted in his young mind.

Whether or not at the age of fourteen or fifteen he had already formulated a nationalist solution as he claims, one can readily accept that Nathan Birnbaum’s early life experience had made him pessimistic about his society. His parents had chosen to live in a cosmopolitan city that differed radically from the mores and pace of life of the provinces from which they came. Like many Jewish immigrant families from Galicia, there was probably a mixture of German and Yiddish spoken in the home. Although not particularly poor for their place and time (young Nathan was left with an inheritance of fifteen hundred gulden), neither were they wealthy; but with Menachem Mendel’s passing in 1875, the family was left without its head and sole provider. The urban surroundings that the young Birnbaum encountered in the imperial capital may also have been a source of anxiety. The 1860s was undoubtedly a decade of great optimism, not the least because Jews had been granted full legal emancipation with the creation of the Dual Monarchy in 1867. But at the same time, the dark clouds of simmering anti-Semitic resentment were beginning to gather and would soon resolve themselves into a persistent feature of Viennese social and political life, targeting with the most viciousness immigrants exactly like Birnbaum’s parents. Birnbaum as a young child was thus confronted with several destabilizing elements. His inability to find solace in the normal quest for a comfortable middle-class life likely played a significant role in his youthful alienation.

The result of this discomfort for Birnbaum was an intense preoccupation with the study of Jewish subjects from the moment he entered the Vienna University. He quickly lost his doubts about the potential for a Jewish national awakening. “Of course, the resignation I felt . . . soon fell by the wayside. I began to look at the Jews as a particular people, with a unique history and a unique, territory-based future, and undertook to enlist my acquaintances to my worldview. . . . [I] began . . . to learn from the Hebrew Bible that my father (may he rest in peace) had taught me from as a youth; I took an instructor in Talmud and read Jewish, especially Hebrew newspapers. Through them I became apprised of the Jewish-national movement in eastern Europe.”9 As a young university student, Birnbaum found a few others who shared his discomfort with the German culture that his Gymnasium schoolmates imbibed so readily, and he shaped his alienation into proto-Jewish nationalism.

Birnbaum attributed the impulse to deepen his Jewish learning to an internal drive, but this was only part of his motivation. Also crucial was his relationship with two men he met in his first months at university, Moritz Schnirer and Reuben Bierer. Schnirer and Bierer were both medical students in the university and shared a similar background. Each was born outside Vienna and came to the city as an adult: Schnirer was from Bucharest, and the forty-six-year-old Bierer was a surgeon from Lemberg who had come to Vienna with his family to become certified as a medical doctor. Like Birnbaum, both shared a deep dislike for what they perceived as the mass denial by Viennese Jews of their core identity. “[Birnbaum] felt a deep shame over the worthless obtrusiveness of Viennese Jews and most of the Jewish students,” Schnirer wrote, “and he realized that, under the veneer of liberalism and freedom festered spiritual enslavement, self-deception, and self-negation.”10 Although Schnirer and Bierer met first, Schnirer quickly brought the trio together by introducing Birnbaum, who, he recalled, was an “exceptionally intelligent, earnest young man filled with a glowing love for Judaism.”11 The three became close associates and formed an informal Jewish studies reading group; Bierer, himself seasoned by affiliation with the Hovevi Zion in Lemberg, assumed a sort of leadership role over their studies and developed a basic curriculum.12 Schnirer wrote of himself later in life, “Bierer, despite being overworked . . . seeing these two young students without direction, without the means or the experience sufficient for such a great undertaking, came up with a fantastic program. They first began to immerse themselves in Hebrew literature and the writings of Peretz Smolenskin.”13

The Creation of Kadimah

The informal reading group that Bierer, Schnirer, and Birnbaum formed quickly evolved. Adding student members such as Bialystok native Israel Niemcowicz, the group attracted the attention of Hebrew writer Peretz Smolenskin, whose enthusiasm for the group’s program led him to advise the students as they developed their nationalist curriculum.14 By the winter of 1883, and with the addition of a few new members, the society grew into a formal organization and sought official recognition. It was in deciding on a name for their group that Peretz Smolenskin made his biggest contribution to its history (chronically ill, Smolenskin died not long after the group’s founding).15 As Schnirer recalled later, “For weeks on end discussion [of the name] went on to no satisfactory conclusion. . . . The name should be Hebrew and at the same time be easy to pronounce for circles of assimilated Jews; it should sound good phonetically and should allude as much as possible to the program. Smolenskin arrived at the happy solution. His poetic genius is to thank for the name ‘Kadimah,’ with its double meaning ‘forward’ and ‘eastward’ a synthesis of the forward thinking and the Zionist idea.”16 Once a name was chosen, its members, including Birnbaum, Bierer, Schnirer, Niemcowicz, Adolf Klein, Isidor Imeles, Leo Schwartz, Ignaz Nadel, Kleomenes Kaplan, Emil Blumenfeld, and Moritz Springer, met in Bierer’s apartment on Kleinen Schiffgasse in Leopoldstadt.17 As Schnirer recalled, “Bierer, the oldest of the circle, gave an address in which the entire wealth of this modest man’s soul was laid open, making an indelible impression on every participant,” and the language of Kadimah’s charter was formulated with the following goals: (1) resistance to assimilation, (2) recognition of the Jewish nation, and (3) furthering the colonization of Palestine as the means of constructing a Jewish com...