![]()

1

A POSITIVE NEGOTIATION FRAMEWORK

Ask any executives attending a negotiation workshop what they seek, and they will say they came to learn the most potent evidence-based tactics to persuade others and increase profits. More sophisticated negotiators, often more experienced, explain that they are looking to persuade others to cooperate and embrace a win-win approach. Nobody attends to better understand themselves. But those who do learn about themselves reap tremendous returns and subsequently send their teams, even their competitors, to become more effective negotiators from the inside out.

Over the past two decades, I have worked with for-profit and nonprofit executives and their clients to better understand their negotiation challenges. To help them succeed, I have pushed the boundaries of negotiation research and developed a theory of positive negotiation. Whether you are negotiating for positive results or simply would like to feel positive about the negotiation process, a positive lens illuminates elements of negotiation that frequently go unnoticed. My positive framework broadens and deepens our understanding of the social interactions that constitute the negotiation encounters we experience on a daily basis.

If you work with people, negotiating is one of your most prevalent daily activities—whether you consider it that way or not. Negotiations definitely include formal mergers and acquisitions, procurement, and sales. More frequently, we negotiate when we brainstorm about ideas, tasks, roles, innovation opportunities, and strategy. A common definition of negotiation describes it as a situation in which at least two people interact and decide how to allocate a resource. Sometimes the resource is money, for example price or salary. Other options include time (how much time to spend on a project), roles and responsibilities (who does what), and psychological resources (energy, responsibility, or blame when things get derailed). The way I view the world, it may be more challenging to find an interaction at work that is not a negotiation.

For many people, a snapshot of a negotiation includes people wearing business suits, sitting at opposite ends of the executive suite. In the United States, another image is sitting at a car dealership, waiting for the salesperson to return to the desk with a response from the sales manager. But most negotiations are neither so structured nor rigid. Many negotiations do not take place around a table. A broader interpretation suggests that negotiations can happen in any place, at any time. They are fluid and often casual.

Executives often learn about the resources on the metaphoric table and the communication across it. The key to negotiating genuinely is examining who you are at the table.

WHO AM I WHEN I NEGOTIATE?

The process of negotiating genuinely begins with the internal question, “Who am I when I negotiate?” Are you only a businessperson representing yourself, or your company, with the sole purpose of maximizing shareholder value? Or perhaps you focus more on stakeholder value? Does being a businessperson lead you to ponder, “To win, do I need to take on an inauthentic negotiation identity?” Many people feel pressured to adopt a style they believe is expected in business.

What if you could just be you? The best you?

The way that we think about ourselves as negotiators relies, at least in part, on the way that negotiation is ritually conceived. This can be traced back to clear intellectual roots. In line with its origins in mathematical modeling and economics, the focus of much early negotiation research was on resources, not people. In the past three decades, negotiation research has been influenced by psychology and sociology, and yet much of this research focused on people’s deviations from rationally maximizing resources. Research has been theoretically grounded in a social exchange approach, which views relationships as socioeconomic transactions of material and nonmaterial goods. It has produced important insights about how resources are, or are not, maximized and how they are allocated. It has also produced insights about the context of negotiations, and how communication, personality traits, and culture influence negotiations.

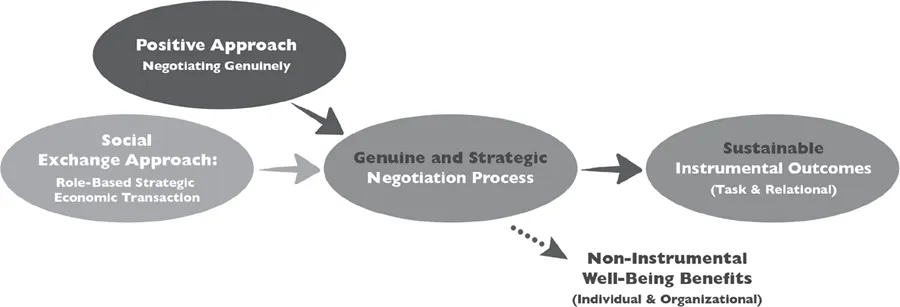

Established negotiation theory assumes that people engage within the capacity of their role to trade ideas, emotions, or goods. These encounters lead to two sets of outcomes that concern negotiators: task outcomes such as financials, and relationship outcomes such as reputation or long-term productive business relationships (see Figure 1.1). This approach is quite broad to describe the goods that might be exchanged. Some academics even describe marriage and love as social exchange processes with transaction costs and opportunities. Likewise, the established approach is broad in that it includes both task and relationship processes and outcomes and considers objective and subjective utility models. However, it is constrained in how it conceptualizes the identity of the players (role players) in the exchange. Although most negotiation research does not explicitly refer to economic frameworks or social exchange theory, these assumptions drive the way negotiations are framed.

FIGURE 1.1. Negotiation through the lens of economic social exchange

Despite great advances in theory and practice, I believe that the established approach constrains how we view the people who negotiate.

First, this approach assumes that people in business are solely role-senders, people who hold a defined role or set of roles, representing a business entity. Roles and position are important, as they define the scope of responsibilities and empower people. But they may also have negative, unintended consequences such as narrowing the identity that surfaces in a given situation or negotiation. For example, a CFO might be more likely to take a leadership perspective and focus on broader and longer-term horizons of your firm’s financial strategy. However, how likely would she be to consider the basic human values that are salient to her as a mother or daughter?

If you are an American negotiator, given that U.S. corporate culture separates work and family, you are probably less likely at work to draw on knowledge and wisdom that informs decisions you make outside of work. This can be a real drawback. Consider your cultural background and the business culture in which you are immersed. When you negotiate, to what degree does your business identity empower you and in what ways does it constrain you?

Second, given the established approach to negotiations, many people assume that being a strategic negotiator requires them to strive to be solely economically rational. It is important to note that economically rational self-interest can be aligned with maximizing joint gains; the more resources available, the larger an individual’s potential portion. Thus a competitive businessperson would also cooperate to further maximize individual profits. To whatever degree you emphasize competition or cooperation, do you, personally, conceptualize yourself as an economically self-interested and rational businessperson? Are you solely inclined to maximize your own subjective utility? Theory assumes this. However, many people do not necessarily feel this way. Business culture often reinforces and emphasizes economic rationality. Consider your stereotypical negotiation persona. Is it grounded in an economic-rational perspective, along the lines of the research framework that I’ve just described?

NEGOTIATING BEYOND ROLE

The positive theoretical approach at the base of negotiating genuinely incorporates and augments the economic social exchange model (see Figure 1.2). The role-based economic transaction depicted in Figure 1.1 does not disappear. We do function as a member of the marketing department, a procurement officer, a hair stylist, a waiter, or a bank teller. This reality does not go away.

In parallel, beyond any combination of roles, we also engage as full, integral, and genuine persons. Engaging beyond roles and adopting a positive genuine approach enables additional generative processes to transpire when people interact (the negotiation process in the middle of Figure 1.2). The interaction is both strategic and genuine. A strategic and genuine process enhances instrumental negotiation outcomes, such that traditional outcomes, for example, profits and reputation, become more sustainable. Furthermore, genuine and strategic interactions spark well-being benefits that would not be captured by a traditional economic model.

FIGURE 1.2. A positive approach to negotiations: Being strategic and genuine

When you negotiate genuinely, the process is no longer solely strategic. To be genuine suggests that you need to engage in a way that also resonates with you, as if you have no goals. Or more precisely, in a way that resonates with the you beyond the business roles and positions you hold (such as corporate lawyer, nurse, fundraiser, chef, or interior designer) and their associated goals.

To excel at economic social exchange, you also need to adopt a positive approach and negotiate genuinely.

Being genuine is not the same as being authentic. Authenticity can be fabricated. A restaurant touting authentic French cuisine does not necessarily provide a genuine French experience. Authenticity suggests the attributes of the original thing are reconstructed, but does not necessarily refer to the genuine construct. For example, a tourist attraction may mimic the archaic Roman Cardo (a north-south-oriented street in Roman cities) and construct an authentic experience for people visiting and shopping in a particular city. However, if you are lucky, there are places in the world where you can see genuine archeological remnants from the Roman Empire, and also genuinely experience them as the Romans may have thousands of years ago. I was fortunate to attend concerts in an original Roman amphitheater. During the day, it is a tourist destination, but at night it is a local theater. Sitting in the same exact seats and imagining who sat there two thousand years ago was a wonderful experience that provided a deep connection to people and to humanity. Genuine experiences fuel deep connections.

Architects and leaders may construct or fabricate authenticity, and negotiators can too. The pretense of authenticity quickly can lead to reputational damage. Being genuine can provoke anxiety about revealing oneself, but it has a tremendous upside. Being genuine does not mean telling everyone everything all the time, as of course that would not be wise. It does not even suggest putting your cards on the table or being overly cooperative. It suggests mindfully, and appropriately, revealing yourself in negotiation. To do so, you need to be your full self in the moment—not a partitioned identity, wearing a discrete hat.

Being genuine is an ongoing pursuit. Becoming a genuine negotiator is about integrating yourself. It requires intentional and iterative internal negotiations that acknowledge and resolve what at first glance may appear to be paradoxically contradictory, or overly harmonious clusters of yourself. It’s about simultaneously being you, for example, the CFO, a mother, an employee, an American, or so on, without being stuck or limited by your roles, positions, or a particular identity. This book is about the continuous process of becoming a genuine negotiator who crafts positive processes and outcomes.

A genuine approach does not preclude use of power, such as setting boundaries, or expressing negative emotions, such as sadness, anxiety, or anger. Sometimes power and negative emotions lend a capability to illuminate and lead people to address important and difficult topics. For example, expressing anger about a potential ethical breach may clarify a loophole or sharpen a boundary. And if it comes from someone who rarely expresses anger, it would also communicate the importance and urgency of the matter. Thus anger could enhance positive negotiation processes and outcomes. On the other hand, being happy and friendly sometimes leads people to avoid addressing key concerns. Issues may remain unresolved, preventing positive negotiation outcomes. Being genuine, in this sense, is not the same as being solely nice. Nor is it about communicating the first thing that comes to mind. Negotiating genuinely requires mindful integration and alignment of positive and negative emotions toward constructive resource-generating conversations. Conversations that address the core interests and priorities of all negotiators enable negotiators to co-create value and reach extraordinary instrumental and non-instrumental outcomes.

In this book, I will lead you on a path that explores how to internally negotiate your multiple identities and become the integral, and therefore genuine, you in business. I will demonstrate why negotiating genuinely is important in negotiations, a challenging task in which to succeed you need to simultaneously cooperate and compete. We will then assess what happens when you genuinely engage in business relationships. Finally, we will examine how negotiating genuinely enables emotion management in challenging conversations and discover how, reciprocally, emotion management helps maintain a genuine approach.

Before moving ahead to further explore what it means and how to adopt a positive approach, to negotiate genuinely, let’s take a moment to explore the strategic task in which negotiators are situated—a negotiation.

RECOGNIZING NEGOTIATIONS

Many books have been written about the successful economics and psychology of negotiations. Some are based on personal experiences; others are evidence-based and build on systematic empirical research (see the recommended readings at the end of this book). Despite the plethora of research, there is no formula of tactics a negotiator can learn and always apply. There are discrete evidence-based tactics that will likely lead a negotiator toward predefined goals, such as anchoring by making the first offer on price to maximize individual gains. But any tactic depends on the uniqueness of the individuals involved, the business context, situational factors, cultural nuances, and the manner in which the tactic is deployed. A wise and knowledgeable negotiator must assess the situation and decide if a tactic is appropriate, or choose which tactic would be best. Although there is no magic formula for tactics, there are strategies that consistently guide a negotiator toward successful outcomes. To successfully negotiate and implement these strategies, you need to recognize when you are negotiating.

Take a moment to think about your day. Have you engaged in any negotiations today? At work? Or outside of work? What did you negotiate over? Money? Task responsibilities? Distance between cars on the highway? In some countries, when you keep what you would consider a safe distance from the car in front of you, immediately s...