![]()

PART ONE

Audiences and Actors

![]()

ONE

Opera Aficionados and Guides to Boy Actresses

Ever since the Orchids of Yan was registered, spreading tales of gay affairs,

Year upon year, time after time, a new version is published.

Be it New Poems on Listening to Youth or A Record of Viewing Flowers—

To think that money is actually paid for such frivolous rubbish!

Bamboo-Branch Ditties from the Capital, 18141

Sitting in the balcony of the playhouse, it’s so easy to lose one’s heart; The “old roués” are flush with cash and puffed up with pride. Hoping for nothing but a smile bestowed from behind the curtain, Even thousands in gold can’t buy them the joys of the “exit-door” side.

A String of Rough Pearls, 18092

Opera wielded a seductive power over its audiences in late imperial China. As revealed in these two Chinese-style limericks, or “bamboo-branch ditties” (zhuzhici), which were recorded early in the nineteenth century, the allure of the world of theater and the charm of its performers could lead literate men to squander their money on doggerel written in praise of actors and could turn wealthy men into pitiful fools for love.

The first limerick offers a tongue-in-cheek assessment of texts known as huapu, texts that evaluated the looks and talents of opera actors. Huapu came into vogue in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Part biography, part display of poetic virtuosity, and part assorted trivia about the demimonde of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Beijing, this genre of writing primarily recorded the skills and exploits of actors who performed the dan role, that is, youths who cross-dressed to play the part of young women characters in various regional styles of opera (or, as I will call them, the boy actresses). This particular limerick not only identifies the huapu genre but also explicitly refers to the first text of its type, A Brief Register of the Orchids of Yan (Yanlan xiaopu), written by Wu Changyuan and printed in 1785. Yan refers to Yanjing, the name commonly used for Beijing during the Qing dynasty, because Beijing is located in what was once the territory of the ancient state of Yan. “Orchid” (lan) refers specifically to the actor featured centrally in Orchids of Yan (who was noted as an amateur painter of orchids on folding fans) and alludes more generally to the “flowers”—the cross-dressed boy actresses—of the metropolitan stage. The limerick is simultaneously dismissive of the quality of writing in huapu and revealing of their popularity: these texts were published “year upon year, time after time,” and apparently sold very well.

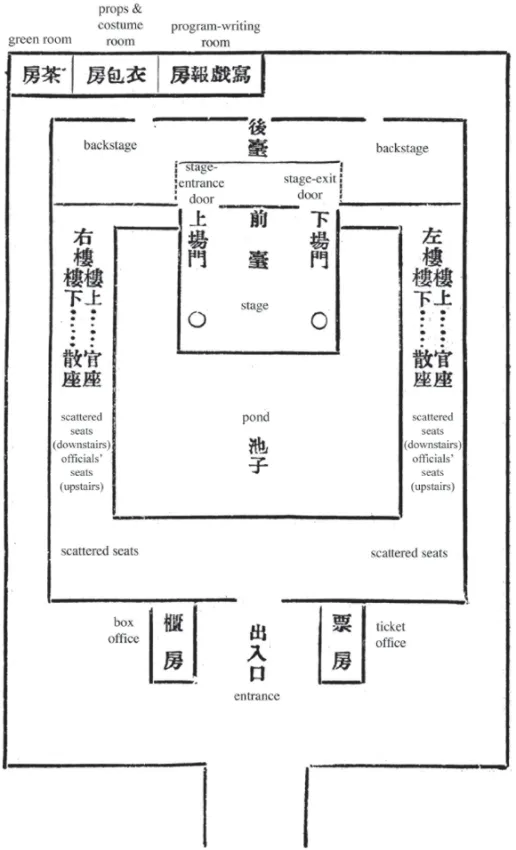

The second limerick caricatures a certain type of opera fan, the “old roué” (lao dou), or, more colloquially, the “sugar daddy.”3 The lao dou was characterized as a theatrical patron who had a surfeit of money and time on his hands and who indulged in the pleasures of the theater (including the purchase of intimate relations with boy actresses and entertainment after performances in the winehouses ringing the commercial playhouse district). Not necessarily elderly, he was old relative to the actors he ogled; and the “old” in this appellation is more an honorific (if laced with sarcasm) than a descriptive modifier. Often too, the lao dou is depicted as not entirely in the know when it comes to evaluating the quality of dramatic performances. Rather, he is a bit of a philistine, substituting money for what he lacks in taste and refinement, and easily swayed by immediate sensory perceptions such as pretty faces and revealing gestures. The stereotypical old roué also had a penchant for sitting in the seats facing the onstage exit door (xiachang men), what we would call the stage-left balcony seats (Figure 1). Within the commercial playhouse these seats were highly coveted because they afforded patrons the best angle from which to exchange meaningful glances (diagonally across the stage) with actors entering the stage through the entrance door (shangchang men), upstage right. As one mid-nineteenth-century huapu author put it: “The most expensive . . . seat is the second one in the ‘exit-door box,’ as that is a convenient spot from which to intercept a sign of the heart or the wink of an eye sent as [an actor] pushes aside the curtain to enter. As a bamboo-branch ditty [says]: ‘a dizzying glance flies to the balcony above; it clinches a date for dinner tonight.’ ”4

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the floor plan of a typical Qing-era playhouse. Adapted from Aoki Masaru, Zhongguo jinshi xiqu shi, p. 513.

The image of the opera fan, whether the lascivious lao dou or the more sophisticated connoisseur, cannot be separated from huapu, which captured and recorded (sometimes with willful distortion) these characterizations of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century theater patrons. In fact, much of what is known about opera performance in Beijing during the Qing—about actors, about styles of singing and acting, about management of commercial playhouses, or about commonly performed plays—is culled from huapu. Chinese-language scholarship on Qing-dynasty opera has assiduously mined huapu for nuggets of historical fact but has largely ignored them as a literary genre or as a source illuminating the cultural practices of the entertainment demimonde.5 A recent English-language study by Wu Cuncun has relied upon huapu to reconstruct a history of male same-sex desire in the Qing.6 But whether writing theater history or social history, scholars have generally looked through—but never at—the huapu.7 In contrast, I treat the literary claims of the huapu seriously as texts of theatrical connoisseurship; by taking a close look at the various discourses constituting huapu, I aim to gain a more nuanced reading of the social and cultural practices of metropolitan theater in the Qing. The huapu turn out to be as revealing of their author-aficionados as of the actors they wrote about, opening a window onto a middling stratum of literati culture in the late empire.

The production of huapu texts came in two waves. During the second half of the eighteenth century the circulation of huapu in manuscript and in print emerged in tandem with the maturation of a vibrant commercial playhouse culture in the Qing capital. Testament to a metropolitan theater that had become—in the words of its fans—“foremost throughout the realm,” these texts were a phenomenon almost exclusive to the capital; although the authors of such texts came from various locales throughout the empire, with few exceptions all huapu or huapu-like memoirs were about the actors and demimonde of Beijing.8 During the mid-nineteenth century the cataclysmic crises of civil war and foreign aggression slowed the tide of flower-register writings. When huapu production picked up speed again in the 1870s, such texts began to shift their focus from cross-dressing dan actors in a variety of commercial opera genres to critical assessment of a wider array of theatrical role types and increasing attention to northern styles of performance. My readings are based on the extant huapu compiled from 1785 through the first half of the nineteenth century (approximately fifteen works), the first wave of huapu production. These texts especially capture a waggish—even permissive—mood that is rarely associated with Qing intellectual culture, and for this reason, too, are worthy of consideration.

Central to texts of connoisseurship in general and huapu in particular is the concept of evaluative classification (pin), used to rank everything from poetry to people. I begin, therefore, with a brief discussion of this concept and the history of its use, showing how allusions to pin enabled Qing theater enthusiasts to position themselves in debates about taste and distinction. Next, I place the Qing-dynasty huapu in the tradition of evaluative biographies of entertainers that dates from Sun Qi’s late ninth-century Chronicles of the Northern Quarter (Beili zhi). Writers of huapu engaged in what I call a “borrowed discourse,” invoking the language, imagery, and tone of earlier texts on courtesans and actresses to assess adolescent males specializing in female roles. In appropriating the rhetorical strategies used for courtesan entertainers to record the charms of boy actresses, huapu writers signaled their perception of opera players (especially of the dan roles) as purveyors of erotic as well as theatrical spectacle. Yet I hesitate to cast these chroniclers of the theater in the role of the libertine. Huapu writers stressed that they were seeking sensibility—not sex—and their deft rhetorical positioning signifies their awareness of the stigma associated with the sex trade in boy actresses. Beyond eroticism, the connoisseurs found something deeply appealing about the female gendering of the dan actors: the combined vulnerability and resilience of the imagined feminine subject position spoke to their own senses of self.

Huapu also blended the connoisseurship literature about courtesans with the city guidebook genre. The latter had a venerable history of commenting on the delights of urban theatrical spectacles, beginning with Meng Yuanlao’s 1147 memoir of Kaifeng, A Dream of Splendors Past in the Eastern Capital (Dongjing menghua lu). On the one hand, like guidebooks, huapu served a practical function. They were discursive maps of one segment of the city—the entertainment district—and could be used by would-be audiences to locate the places and people associated with opera in the capital. In this guise, the huapu writer acted as both ethnographer and tour guide, brokering insider knowledge of the metropolitan theater world to outsiders seeking a way in. On the other hand, huapu often exuded a strong sense of nostalgia for cherished places and entertainments. The sentimental, wistful quality of such writings reveals as much about the author and his perceived relation to his object of study as it does about the city and the world of theater itself.

For all the attention that huapu paid to actors and demimonde gossip, the star of such texts was the author. He (and it was always a he) was the opera fan par excellence, the true cognoscente. Through his writings about the theater scene in the capital he could record his aesthetic choices for both his peers and posterity. The voices of these opera enthusiasts ring out the most clearly, whereas the interests and opinions of other patrons and the actors are muted and mediated by the texts that purport to represent them. The writer was often a sojourner to Beijing (frequently from Jiangnan or places farther south), and his prefatory remarks usually traced his trajectory from neophyte to cognoscente. Often depicted as having rejected the “official life,” or its having rejected him, the connoisseur drowned his disappointment in obsession with the theater. His dismal prospects in public life—resulting from a lack of recognition of his talent—moved him to identify with the lowly actor and partly drove his interest in recognizing, ranking, and recording the skills of actors. The connoisseur as huapu author was concerned with both the physical charms and the artistic prowess of the actors he cataloged, but he insisted that it was his appreciation of talent that distinguished him from less sophisticated fans.

His protestations to the contrary, the flower-register connoisseur was nonetheless also clearly fascinated with the seedier side of the opera world but cloaked this interest in ethnographer-like comments about the taste of the lao dou, whom he often characterized as “great patrons” (hao ke) or “wealthy merchants” (fu gu). The huapu writer’s distinctions between self and lao dou betray his unease about class and status, likely fostered by the manner in which he partook of the theater. The flower-register literature of opera connoisseurship was a by-product of the mid- to late Qing commercial playhouse. Unlike their late Ming literary exemplars, who mostly experienced and wrote about theater in private settings, the men who chronicled eighteenth- and nineteenth-century opera had to share their experience of it with anyone who could afford the ticket price. This troubled them. By their own accounts, they shared the playhouses with men whom they considered their social and cultural inferiors. Through appropriation and transference of the world of performance to the page, these connoisseurs were reinventing (and reclaiming) a status distinction that was being eroded in the socioeconomic sphere.

The Texts

The introductory passage to Wu Changyuan’s Orchids of Yan combines a clever mix of whimsy and precision:

Orchids are not native to Yan, and yet the Commentary of Master Zuo [Zuo zhuan] records that Consort Ji of Yan had a dream about an orchid in which she was told: “The orchid is the lord of fragrance, and so men are won over to it.” Thus, we know that the intrinsic virtue of the orchid has been recognized both in the north and in the south. It was midsummer of 1783; [the actor] Wang Xiangyun had a penchant for making ink-brush paintings of orchids. Because he painted several stems of orchids on a folding fan, I, together with some like-minded friends, took a sudden fancy to elaborate upon this gay amusement by making a record of it. My idle humor not yet abated, I further culled and assembled lore on the best actors to create A Brief Register of the Orchids of Yan. This work covers altogether fifty-four actors from 1774 to the present and records 138 poems about them. It also contains a total of fifty entries of miscellaneous verses, anecdotes, and hearsay. It begins with the poems on painting orchids in recognition of its original inspiration. It follows with the entries on the “orchids of Yan,” which praise the various actors. It ends with verses on a variety of subjects, which are invested with sardonic words of caution.9

In this recollection of a summer’s lark Wu’s pleasures in the theater and in the literary games of polite society are reined in and ordered by classical allusion, meticulous detail, and numerical particularity. In style, tone, and content this “register” of opera actors ushered in a subgenre of connoisseurship writing about performers, especially about actors playing the dan roles. The three main features of Or...