![]()

PART I

The Nation in the World, the World in the Nation

![]()

1

IN THE CRUCIBLE OF WAR

Immigration, Foreign Relations, Democracy, and H. L. Mencken

ONE OF US?

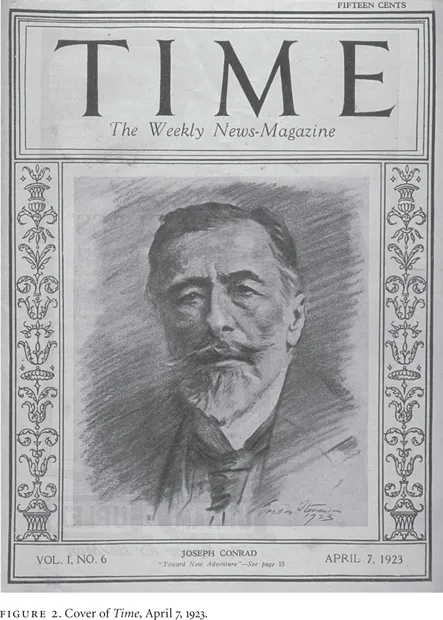

On April 7, 1923, Joseph Conrad appeared on the cover of America’s Time magazine. The occasion was Conrad’s first and only visit to the United States, which began in May and was anticipated throughout the preceding month. The mood was one of high romance, as Conrad, “rover of the seven seas” and “probably the most exalted [figure] in contemporary English letters,” was finally embarking on the most exotic adventure of them all:

Despite all the countries and seas of the world which he has made his own and presented to his readers, Mr. Conrad has never come closer to this coast than on the first voyage of his sea-life in 1875, which took him through the Florida Channel to the West Indies. It will be our especial opportunity to greet him here at last.1

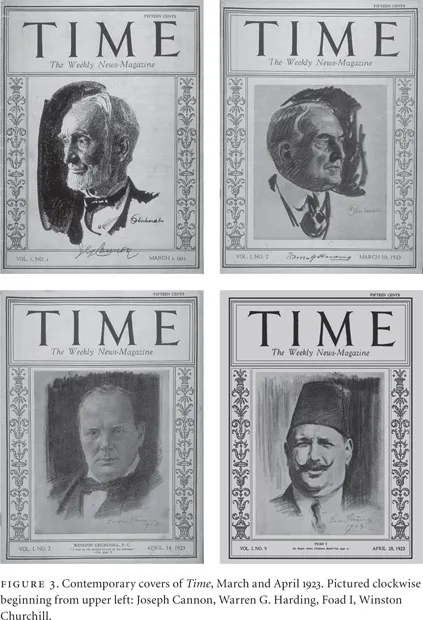

As these words suggest, there is a curious element of destiny and circular homecoming that underwrites this narrative of ultimate distance, a paradox registered in the two mythic figures most widely in circulation to gloss Conrad’s latest journey: Ulysses, the archetypal alien wanderer, and Columbus, the “discoverer” and a narrative foundation of “America.”2 This paradox is also registered in the picture on the cover of Time, unique in its artistry among contemporary numbers of the magazine (see Figures 2 and 3 on pages 44 and 45). There is a portrait of Conrad looking very much the familiar venerable writer: stately, solemn, neatly anchor bearded, grandfatherly wise. Yet this image of Conrad is embedded in a rush of dark, heavy streaks, not the background for but the occlusive and estranging medium in and through which this Conrad exists. This flattened surface creates an extraordinary—and defining—optical illusion, especially evident in the original glossy format of the Time cover. It presents Conrad simultaneously as a spectral apparition who has come from afar and as a face one might see if one looked in the mirror.

This is the image of the “distant mirror” through which I would have us understand Conrad’s heterotopic construction in and captivation of the American imagination from 1914 to 1939, and it is one quite explicitly and self-consciously used in several U.S. appreciations of Conrad during this period.3 Yale professor William Lyon Phelps, for instance, observes in The Advance of the English Novel (1916) that whereas “Dickens is a refracting telescope, Conrad is a reflector,” and goes on to identify a mirror of the mirror of Conrad’s fiction in the same dualized and shrouded image of Conrad’s face that the Time cover presents visually:

His face to some extent is a map of his soul. He looks like a competent, fearless, and highly intelligent clipper captain. His eyes have looked on the brutality of nature and the brutality of men and are unafraid.… It is a face that knows the very worst of the ocean and the very worst of the heart of man, and, while taking no risks, realizing all dangers, is calmly, pessimistically resolute. This is not a man to lead a forlorn hope, but unquestionably the man to leave in charge; grave, steady, reliable.4

This double Conrad—his “eyes” reflecting both reassuring safety and vast penumbral stretches of distance and darkness—is also presented by Christopher Morley in The Mentor in 1925. Morley, too, begins by introducing Conrad’s fiction in terms of its “mirror” function and then elaborates that function through an even more intensely dualized reading of a recent bust of Conrad by U.S. sculptor Jacob Epstein:

[Conrad] had, as highly as any man of our time perhaps, the genuinely poetic mind which dreams about its experiences in life and, by its magic faculty of seeing secret resemblances and analogies, builds a fable which mirrors ourselves.… The great sculptor Epstein has done a bust of Conrad which has startled some of those who loved him because they do not find it “like the Conrad they knew.” It isn’t: it is great sculpture because it is like the Conrad they didn’t know, that probably no one knew: the secret and fierce and imagination-wracked soul of the great poet—with an enemy in his breast.5

The Epstein bust is, in fact, quite representative of the many curiously and variously distorted images of Conrad in circulation in the United States at the time; but perhaps the most precise contemporary formulation of the “distant mirror” of Conrad’s fiction, struggling through and against difference to arrive at and to erode an image of identity, may be found in the work of idiosyncratic Brown professor, public essayist, and future editor and novelist Wilson Follett (perhaps most famously known for his Modern American Usage). In an important essay in the Atlantic Monthly in February 1917, Follett presents the whole of Conrad’s fiction through the exemplar of “The Secret Sharer”; in particular, Follett emphasizes the captain-narrator’s “secret,” specular fascination with the mutinous Leggatt—who is “the negation of tranquility in a solid and respectable ship’s company,” “a negation of [all] the serene immensity of the cosmos that mocks him”—to theorize Conrad’s fiction in terms of mirror operations that negate and “disentangle” all the artificial boundaries preventing identification.6 Taking his cue from the claim in the Preface to The Nigger of the “Narcissus” that the artist’s “task” is to “awaken” a “feeling of unavoidable solidarity” among “all humanity” (NN ix), Follett argues that Conrad’s characters, always “outside” of and “outcast” from our normative spheres of reference, are nevertheless “so near to being ordinary characters that we see ourselves reflected in them.” The crucial element of this “perception,” however, is not the “nearness to common life” but rather “the strangeness that underlies the familiarity; the strangeness that comes from the something inexplicable and nameless at the center of every soul, which makes it eternally foreign to every other.” Whether with respect to “the mystery of race,” “a world in which East is East and West is West,” or the local psychology through which “everyman [becomes] a foreigner to his neighbor,” “the secret and invisible thing that renders us alien to each other is the thing Mr. Conrad is always trying to disentangle.” Conrad’s fiction, by effecting identification through the negative prism of alienation, comprises a “mirror” through which the “outward wrappings” in which are lives are “suffused” become momentarily collapsed into the space of the alien.7

All of the previous formulations speak to a sense of Conrad’s fiction—as well as his persona, invariably invoked to explain the fiction’s anomalous character and to contain its unstable and contradictory applications—as a matrix of spatio-conceptual difficulty: a shadow-line of foreign and familiar space; an interference in the constitution of boundaried identity; an excess of narrativity that becomes blurred together in a common undifferentiated contact zone; an external virtual vantage through which—as happens when one looks in the mirror—presumptive self-integration itself becomes displaced by an expanded, estranged, reversed, derealized image of one’s self in a world. Such modern U.S. reactions to Conrad, hence, are much like the “sort of counteraction on the position” of the observer that Foucault theorizes of heterotopias through the instance and analogy of the mirror:

From the standpoint of the mirror I discover my absence from the place where I am since I see my self over there. Starting from the gaze that is, as it were, directed toward me, from the ground of this virtual space that is on the other side of the glass, I come back toward myself; I begin again to direct my eyes toward myself and to reconstitute myself there where I am. The mirror functions as a heterotopia in this respect: it makes this place I occupy at the moment when I look at myself in the glass at once absolutely real, connected with all the space that surrounds it, and absolutely unreal, since in order to be perceived it has to pass through this virtual point which is over there.8

Conrad performs this kind of desanctification of space in the modern United States, as I begin to tell the story in this chapter. Offering up an entire “external” world in mirror relation to the United States, the United States becomes not only absolutely realized in all its worldly connectedness and implication but also absolutely derealized (and variously rerealized) with respect to all the narrative and ideological machinery through which the United States has traditionally constructed itself as an emphatically separate, exceptional, self-reliant, self-determined, fundamentally self-contained space. Making the conception of “America” pass through the vantage of the foreign, Conrad becomes an American problem whose contestation and proliferation emerge from the degree to which he turns the United States into a contested space—not by taking a “position” with respect to it but by rendering problematic, susceptible to controversy, as a species of trouble, the very vocabularies through which the United States constitutes itself as a fundamentally distinct and distinctly selfregulated national domain.

Richard Curle, hence, is only partially right in his attempt in 1928 to explain Conrad’s “tremendous” stature in the United States—why “to numbers of Americans, he is the author of all authors, the one writer to whom they pay a single-minded homage”—in terms of “sheer” difference:

At first sight this was astonishing, because the kind of admiration which amounts to worship is usually bound up with deep spiritual affinity, but I have come to the conclusion that it is the sheer exoticism of much of Conrad’s atmosphere which appeals so particularly to the Americans. It is, in brief, the romance of contrast. … [I]t is in romance that one may discover the final secret of Conrad’s hold upon America.… Conrad awakens the American sense of adventure.9

Rather, it is the very question of difference, the very clusters of “American” relations that are unsettled, reasserted, fiercely contested, and finally unfixable in Conrad’s image, that makes for the romance of and with Conrad in the modern United States. “I dare say there were multitudinous Conrads,” Christopher Morley observed in late 1924;10 and from these many Conrads, generating and mediating equally multitudinous fissures and suturings of the U.S. spatial and ideological imaginary, arise many of the signature aspects of Conrad’s discursive production—especially his remarkable ability to be processed on any side of many binaries (cosmopolitan/national; metropolitan/provincial; democratic/aristocratic; elitist/popular; reactionary/radical; aesthetic/political; imperialist/anti-imperialist; masculinist/womanist), and his simultaneous overdetermination and underdetermination by the idea of “debate” itself.11 Conrad, in short, allows modern Americans to ask and engage with unusual depth and extension the “unhomely” question that Conrad’s aptly named Yanko Goorall poses to himself in “Amy Foster”: “Was this America, he wondered?” (TOT 129).12

History, I have suggested, emerging at just the right “slice of time,” is the key to Conrad’s U.S. cultural emergence, and in this chapter we begin to consider the relation between the rise of Conrad as a modern U.S. fascination and the historical threshold and U.S. cultural-political implications and circumstances of the Great War. The focus of this chapter is H. L. Mencken, one of the major oppositional figures in U.S. history and a primary cultural generator of Conrad as a figure of trouble, interference, and neutralizing subversion and inversion in the modern United States. The first section begins by discussing the general terms, affectual and perceptual, of Mencken’s attraction to Conrad, and the exilic positionality that enables Mencken to become a powerful disseminating force of Conrad—well beyond his own writings and this chapter. The following sections trace Mencken’s specific inscription and construction of Conrad in terms of a triply mapped assault on the idea of the “Anglo-Saxon”—a nexus of foreign relations, racialized response to immigration, and “Puritanical” ethos of democratic government and culture—all made visible and actionable through the crucible of war. The “distant mirror” of Conrad for many modern Americans begins with Mencken—and as we shall see throughout this book, it never entirely escapes him.

AS HLM SAW IT

Mencken’s vigor is astonishing. It is like an electric current. In all he writes there is a crackle of blue sparks like those one sees in a dynamo house amongst the revolting masses of metal that give you a sense of enormous hidden power.… When he takes up a man he snatches him away and fashions him into something that (in my case) he is pleased with—luckily for me, for had I not pleased him he would have torn me limb from limb. Whereas as it is he exalts me above the stars. It makes me giddy. Who could quarrel with such generosity, such vibrating sympathy and with a mind so intensely alive?

—Conrad to George T. Keating, December 14, 1922

The blue sparks of Conrad in the modern U.S. imagination begin with Baltimore iconoclast H. L. Mencken. Though by no means the first American to discover or become passionately attached to Conrad, Mencken was the primary force that first galvanized Conrad as a figure of broad public recognition, and his are the surging volcanic tones—richly and fiercely heterotopic in character—that not only provoked but established many of the terms of the larger American counterpoint of Conrad to follow. This Menckenian awakening of “our Conrad” must be understood in the more general context of the literary, cultural, and political impact that Mencken had on the generations that came of age during World War I, an impact that one ignores at the risk of evading a primary cultural interface of “our America.” Described by Walter Lippmann in 1926 as “the most powerful influence on this whole generation of educated people” and by the New York Times in 1927 as “the most powerful private citizen in America,” by his friend Huntington Cairns in retrospect as “the closest embodiment of the Johnsonian dictatorship that the U.S. has ever known,” and by Vincent O’Sullivan in 1919 as simply “the first American critic, since Poe,” Mencken may be considered as something of the Ralph Waldo Emerson of modern U.S. letters.13 In recovering the terms of Mencken’s claims to twentieth-century Emersonian centrality—a proposition I advance heuristically and historically, not didactically—we begin to recover not only the large field and mechanism of affectual and cultural-political controversy that propelled Conrad’s invention as a master literary figure but also, through Conrad, a good deal of the peculiar genius and complexity of Mencken.

Mencken is sufficiently i...