![]()

CHAPTER ONE

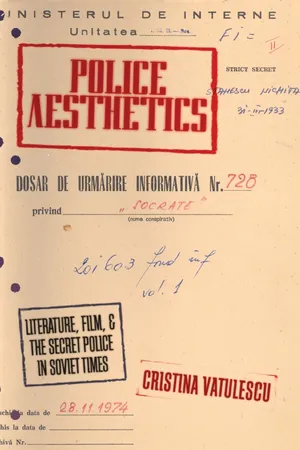

Arresting Biographies

The Personal File in the Soviet Union and Romania

Preamble: Fragmentary Archives

Romanian and Other Eastern European Secret Police Archives

The story of the partial opening of the secret police archives in Eastern Europe is often as instructive as the declassified files themselves. Anything but relics of the Cold War destined to the dustbin of history, the archives are at the very center of contemporary politics. Indeed, one could write a comparative history of post-1989 Eastern European politics by following their fate. Such an undertaking is well beyond the scope of this study; instead, I will briefly trace the story of my own access to materials used in this chapter, contextualizing that story within the larger discourse on the secret police archives.

The recent fate of these archives in Eastern Europe is a vivid, indeed often lurid, illustration of Jacques Derrida’s pronouncement that “there is no political power without control of the archive, if not of memory. Effective democratization can always be measured by this essential criterion: the participation in and the access to the archive, its constitution, and its interpretation.”1 Other theoretical concepts generated in poststructuralist rethinking of the archive, such as the return of the repressed or the death drive, were similarly literalized as Romanian villagers unearthed thousands of pages hastily buried by the secret police. Foucault’s thesis that the archive is not just a collection of documents but the whole power structure around them, or Derrida’s point about the “house arrest” of res publica by the archons of power, was similarly propelled far from theory books and into tabloid headlines through the story of the secret police heirs’ sabotage of the opening of the archives.2 Starting with the archives’ long anachronic classified status, and continuing with the delivery of the files into the rain as the successors of the secret police withheld first the space designed to house them, then the finding aids or reading know-how needed to decipher them, the story unfolded and still unfolds as unendingly as the serialized “telenovellas” that competed for transition-weary audiences.

Throughout Eastern Europe, the more or less reformed successors of the secret police who inherited the archives proved stubbornly opposed to opening their doors. These were sometimes burst open by public pressure, most dramatically by angry East Germans who made it inside the STASI archives and onto television screens worldwide.3 However, in the rest of Eastern Europe, early access to the secret police archives often happened behind the scenes, as well-timed revelations and leakages of the files attempted to compromise leading political players.4 The introduction of lustration laws in most Eastern European countries, with the notable exception of Russia, was designed to address, or sometimes just feign to address, these problems; but everywhere, lustration laws brought the archives even closer to the center of contemporary politics and fueled heated debate.5 Variously applied in different countries, lustration laws mandate that the past links of present-day politicians with the secret police be checked in the latter’s archives and made public. The consequences of these revelations vary, as lustration laws were designed and implemented differently from country to country, and also within countries in close relationship to the changing fortunes of the powers that be.

I started my search for secret police files in the late 1990s in Romania. It took ten years from the 1989 Romanian Revolution for a law to be passed founding the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archives (Consiliul National Pentru Studierea Arhivelor Securităţii or CNSAS)6; its role was to allow civil society to check the secret police ties of public figures, from the president to post-office managers, and also to allow private citizens access to their own files. CNSAS was to be led by a council of eleven representatives of the leading political parties. At best, this arrangement signified democratic pluralism; at its worst, it meant that the council’s activity was often nearly paralyzed by the wide differences among its leaders, some of whom represented parties which fought to close CNSAS and all access to the archives. Because of these internal as well as external pressures, CNSAS often proceeded by fits and starts and took over the secret police archives slowly and only partially.7

In the hope of some edification about gaining research access to the former archives of the Securitate, I sent e-mails to the webmasters of all eleven political parties asking for the contacts of their CNSAS representatives. I got only two responses, but they allowed me to contact the representative of the Hungarian minority’s party, Ladislau Csendes, and then president of the CNSAS, Gheorghe Onişoru. My two contacts, both academics, welcomed my project and invited me to attend the training sessions organized for the employees of CNSAS. This turned out to be an unparalleled opportunity to witness the foundational work of CNSAS. The sessions took place in Ceauşescu’s megalomaniac palace, Casa Poporului, and I remember getting perpetually lost in the labyrinthine hallways, trying to make my way to rooms where senior officers of the former Securitate services were teaching fresh graduates of history departments how to navigate the archives and read files. Everyone looked out of place in the grotesquely oversized private residence, decorated in a boudoir version of socialist realism: the Securitate officers, pacing awkwardly in front of the room, unaccustomed to public lectures; the young historians, visibly excited to have landed their new jobs, although not quite sure what they entailed; and the senior members of CNSAS, many no doubt subjects of secret police files, watching their former watchers expose surveillance methods.

By the summer of 2000 I was working in the archives of the CNSAS. Since the question of research access had not yet been fully settled, I was often the first researcher to gain access to the files of major Romanian writers, such as Nicolae Steinhardt, Marin Preda, and Nichita Stănescu. Besides offering access to personal files from the whole period of communist rule, CNSAS also made available to me internal Securitate regulations regarding the organization of the archives, as well as the conduct of surveillance, arrests, investigation, and informer recruitment. In the meantime, CNSAS publications, such as an extraordinary collection of the Securitate internal regulations used extensively in this study; independent publishers; and even SRI (Serviciul Român de Informaţii) publications have made a wealth of secret police documents available for public scrutiny.8

A Case Apart: Russia’s Former KGB Archives

Russia never passed a lustration law. Such a law was drafted in 1992, but it failed miserably on the Duma floor.9 At the same time, the Duma passed laws making it a criminal offense to identify former secret police agents and collaborators.10 As a result, access to the archives followed a different route from elsewhere in Eastern Europe. And yet the beginnings had been promising: in 1991, Boris Eltsin established a parliamentary commission to investigate the status of the former secret police archives. The published reports of members of this commission are an invaluable source of information concerning the overall state of the archives. Nikita Petrov reports the commission’s finding that in 1991 there were 9.5 million files. He also gives figures for the main types of files (personal or “operational” files, personnel files, files confiscated from Nazi camps, and administrative files) but warns that these numbers are not reliable since many files have been destroyed, legally or illegally.11 His view regarding the KGB treatment of the files is summarized in his title: “The KGB Politics Regarding Its Archive Was Criminal.” Another important study, cowritten by a commission member, Arsenii Roginskii, with Nikita Okhotin, provides a more detailed description of the typology of the files as well as a thorough account of the activity of the commission and of the power struggles that by 1992 had already hindered the ambitious plans to open the archives to the public.12

The archives have instead remained under the jurisdiction of the successor to the KGB, the FSB, which has jealously guarded them from both public and research access. However, alternative sources of information on the archives, when put together, amount to a rather different and highly instructive portrait. The glasnost years saw the first successful efforts to open the archives. Already in 1988, heeding the initiative of Vitalii Shentalinskii, the Writers’ Union established a commission aimed at recovering the manuscripts of repressed writers as well as their files. After countless tribulations, supported and hindered at the highest levels of party and KGB leadership, the commission made its way into the archives and emerged with files of leading cultural figures, such as Isaac Babel, Mikhail Bulgakov, Maxim Gorky, Osip Mandel’shtam, and others.13 Shentalinskii edited these finds in two volumes, which remain to this day an unparalleled source of personal files from the peak of Stalinist repression. Precisely because it was such an extraordinary success, this experience also spelled out the limits of archival access: the commission, backed by the weight of leading cultural figures as well as high-level official sanction, was allowed to see only selected files from the Stalinist period, the safely distant and publicly denounced period of “the cult of personality.” Even such selective access was still denied to independent researchers and private individuals.

This changed in 1991 when repressed individuals gained access to their own files according to the law concerning “The Rehabilitation of the Victims of Political Repression.”14 According to the FSB, around two thousand people take advantage of this right every year.15 Some of them have made files public, either independently or by adding them to collections such as the pioneering Memorial Society archive, thereby filling in gaps of official disclosures by offering information concerning more recent periods of Soviet history.16 Significant collections of secret police documents, often its correspondence with other institutions which have made their holdings available to researchers, have accumulated into a substantial, if indirect, archive.17 Furthermore, the partial opening of the archives in certain former Soviet republics, such as Latvia and Estonia, has revealed significant information about the Soviet secret police. Thus, a KGB textbook on the history of the Soviet secret police from 1917 to 1977, which remains top-secret material in Russia, can be accessed online thanks to the opening of Latvian archives.18 As Peter Holquist wrote in surveying post-Soviet historiography, “the problem is not [primarily] one of archival access to relevant materials, but of our ability to work through them. . . . Tellingly, the most representative genre of post-Soviet historical study is the documentary compilation, bursting with primary source documentation but eschewing interpretation.”19 This chapter takes on the task of analysis and interpretation and offers the first sustained study of the secret police personal file in Soviet times.

We are certainly far from a comprehensive picture of secret police archives in Eastern Europe. In Russia, the near future does not promise much in this respect.20 Elsewhere in Eastern Europe, the opening of the archives is at best in process, with much yet to be unearthed. But rather than waiting for the heirs of the secret police to invite us to the grand opening of the archives, I think it is time to pick up and analyze the available pieces of declassified or leaked information. When cobbled together, they result in a substantive, if often indirect and fragmentary, archive. With all its drawbacks, this fragmentariness is an instructive antidote to a problematic fantasy of the complete archive.21 The secret police never kept complete or truthful records, and it has often destroyed the records it did keep. These gaps were often deliberately created to compromise the value of existing archival collections as incriminating evidence to be used in the administration of retroactive justice. It is telling that the successors to the secret police remind us with hardly dissimulated satisfaction that informer records have been partly destroyed.22 As a result, no one can be absolved of the accusation of having collaborated with the secret police—it might simply be that the informer’s file has been destroyed. If we go to these archives to find out the definitive answers about our past, we are bound to come back with the answer that we are all potentially guilty. The relativist position espoused by the heirs of the secret police is self-serving and deeply problematic; but also problematic is the initial question, which even while openly incriminating the secret police, betrays an enduring reliance on its power to give us answers to the hard questions of the past and present. Like the door in Kafka’s famous parable, the doors to the secret police archives will not be opened by waiting. And the guard does not have the key. Indeed, there is no one key, just as there is no complete archive; however, the fragments of this incomplete, often indirect, but still sizzlingly active archive give us plenty to explore. So we had better start off.

A Short Genealogy of the Secret Police File

As the name suggests, the secret police file is a variation on the genre of the criminal record. Walter Benjamin wrote that the challenge of identifying a criminal shielded by the anonymity of the modern masses “is at the origin of the detective story.”23 The elusiveness of the criminal’s identity is also at the origin of modern criminology, a discipline that developed in the late nineteenth century around discoveries about matching traces such as fingerprints, bloodstains, and handwriting with the individual who left them. In the 1870s, pioneering criminologist Alphonse Bertillon proposed a method for identifying criminals, which synthesized many of these discoveries.24 His police records combined mug shots, anthropometric measurements of the body, the verbal portrait (portrait parlé), and the record of peculiar characteristics (such as tattoos and accents). By the end of the nineteenth century, the skeleton of the modern police file was already well in place throughout Europe.25

Whereas criminal records are usually limited to the investigation of one crime, the Soviet personal file is typically concerned with the extensive biography of the suspect. Already in 1918, Martin Latsis, a leading Chekist, instructed: “Do not look in the materials you have gathered for evidence that a suspect acted or spoke against the Soviet authorities. The first question you should ask him is what class he belongs to, what is his origin, educatio...