![]()

1

The Polythink Syndrome

Pearl Harbor and September 11

On September 11, 2001, the United States of America was attacked by al-Qaeda terrorists who flew three American jetliners into the World Trade Center towers in New York City and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. The terrorists even aimed a fourth plane at the U.S. Capitol building or the White House before resistance from the plane’s passengers forced them to change course. The plane crashed in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, killing all on board. More than 3,000 people were killed in these devastating events, including 2,606 in the World Trade Center, 246 victims on the four airline flights, and 125 in the Pentagon. The overwhelming majority of these casualties were civilians. Fifty-five military personnel were killed in the assault on Washington. These attacks were carefully planned and executed by Osama bin Laden and his covert fundamentalist Islamic terrorist group, al-Qaeda.

Since the 9/11 attacks, the U.S., and the world, have never been the same. Following the attacks, the U.S. entered the costly War on Terror, launching two wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Today, ongoing unrest in Iraq, Syria, and Afghanistan, the ISIS threat, and other terrorist attacks around the globe continue, with offensive operations by the U.S. in Iraq, Syria, and other countries in the region occurring as well.

Thus, as most academics, politicians, and pundits agree, the War on Terror continues to have profound implications for American citizens and others around the globe in an array of arenas—affecting the economy; individual freedoms and civil liberties; the security of airline transportation; the personal safety of civilians in the U.S., the Middle East, and other parts of the world; and even the conduct of modern warfare itself. However, American foreign policy decisions during these turbulent years have often been criticized as suboptimal or even damaging to America’s interests and security. The central goal of this book is to address this troubling paradox—how do smart, experienced decision makers make faulty policy decisions or experience decision paralysis and inaction in the face of critical foreign policy crises?

Polythink

At first glance, many analysts and laymen alike draw parallels between September 11 and the last devastating attack on American soil that similarly transformed the world. On December 7, 1941, “a date which will live in infamy,”1 U.S. forces in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, were stunned in a deadly surprise attack by Japanese forces, leaving 2,402 Americans dead and another 1,282 wounded. Altogether, the Japanese sank or severely damaged eighteen ships, including eight battleships, three light cruisers, and three destroyers. On the airfields, the Japanese destroyed 161 American planes and seriously damaged 102 (World War II History Info 2010). As with September 11, 2001, this attack was arguably the main catalyst for the U.S. entry into a global war of epic proportions that truly changed the face of the world as we know it today.

But how is it that such a powerful and sophisticated nation as the U.S. allowed both of these deadly attacks to happen in the first place? More generally, how is it that presidents and their policy-making teams—including foreign policy and national security experts—made policy decisions that led to such negative outcomes? Were similar factors at play in both instances? Or was it, as we will demonstrate in this book, the result of two very different, but similarly destructive, types of sub-optimal group decision-making processes at the elite level? Were these foreign and national security decisions and policies that allowed a seemingly militarily inferior enemy to inflict such damage on the American homeland a result of the distinct group dynamics among the military, intelligence, and diplomatic arms of the U.S. government? Namely, were these attacks the result of the phenomenon of Groupthink or of the dynamic we call Polythink?

As we will demonstrate, the group dynamic of a decision-making unit is indeed a vital variable that should be examined in order to understand how policies are ultimately formulated and executed (or fail to be executed at all). Indeed, “foreign-policy making is not simply a matter of a rationalist calculus, which merely requires realist inputs about power and interests to determine choices and outcomes . . . Instead we must think of the decision process as a fundamentally human one . . . To understand how a state arrives at a decision, we must carefully examine the human processes behind that decision” (Schafer and Crichlow 2010, 8).

In The Polythink Syndrome, we focus on the Polythink group dynamic, a phenomenon that can cause otherwise rational decision makers to engage in flawed decision-making processes that deeply affect the security and welfare of a country. Polythink is a group dynamic whereby different members in a decision-making unit espouse a plurality of opinions and offer divergent policy prescriptions, and even dissent, which can result in intragroup conflict and a fragmented, disjointed decision-making process. Members of a Polythink decision-making unit, by virtue of their disparate worldviews, institutional and political affiliations, and decision-making styles, typically have deep disagreements over the same decision problem. Consequently, members of Polythink-type groups will often be unable to appreciate or accept the perspectives of other group members, and thus will fail to benefit from the consideration of various viewpoints.

This book will analyze eleven key national security and foreign policy decisions: (1) the national security policy designed prior to the terrorist attacks of 9/11; (2) the decision to enter into Afghanistan; (3) the decision to withdraw from Afghanistan; (4) the Iraq War entry decision; (5) the decision on the Surge in Iraq; (6) the decision to withdraw from Iraq; (7) and (8) the crisis over the Iranian nuclear program (analyzed from both the American and the Israeli perspectives); (9) the 2012 UN Security Council decision on the Syrian Civil War; (10) the 2013–14 Kerry peace negotiations between the Israelis and Palestinians; and (11) the 2014 decision by the U.S. to engage in targeted strikes against the emergent ISIS threat. Through our analysis of these decisions, we conclude that many of these national security and foreign policy decisions of the U.S. indeed exhibited key symptoms of the Polythink syndrome.

Polythink vs. Groupthink

The surprise attack on the Pearl Harbor base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, has been characterized by scholars as a prototypical example of a policy “fiasco” that was triggered by the Groupthink decision-making syndrome (Janis 1982a). Groupthink is “a mode of thinking that people engage in when they are deeply involved in a cohesive in-group, when the members’ strivings for unanimity override their motivation to realistically appraise alternative courses of action” (Janis 1982a, 9). At the national level, this means that cohesive policy-making groups, such as the advisors to the President, often make sub-optimal decisions as a result of their conscious or subconscious desire for consensus over dissent, which leads to ignoring important limitations of chosen policies, overestimating the odds for success, and failing to consider other relevant policy options or possibilities. The implications of this phenomenon for national security decision making are clear. In a Groupthink scenario, the overarching tendency to strive for consensus and unanimity rather than carefully reviewing a set of diverse policy options and the risks and benefits that accompany each leads to sub-optimal decision-making processes that in turn result in the many policy “fiascoes” with which we are all too familiar, such as the attack on Pearl Harbor (Janis 1982b).

And in fact, since the introduction of Groupthink in the 1970s, much emphasis has been placed in national security and foreign policy decision-making circles on the procedures, processes, methods, and techniques that can be utilized to prevent Groupthink from occurring, such as a leader remaining impartial rather than stating a particular view; dividing the group into subgroups to hammer out differences; bringing in outside experts to challenge policymakers’ views; and assigning specific members of the group to play the role of “devil’s advocate” (George 1972). However, Janis and others have also recognized that many of these policy prescriptions could have detrimental effects if they are poorly managed. These strategies could lead to prolonged debates that could be costly when a crisis requires immediate action, or they might damage good relations between group members. Thus, oftentimes the prescriptions provided by theorists and practitioners for addressing Groupthink leave decision makers at risk of swinging too far in the other direction and contributing to the advent of a very different, but no less detrimental phenomenon that we term Polythink.

While at first glance the Pearl Harbor and September 11 attacks appear to be similar due to their deadly nature, the U.S.’s astonishment and unpreparedness, and the attacks’ resulting massive impact on the global political stage, the reasons the U.S. failed to prevent these attacks were actually quite distinct. Though there was a striking similarity of inaction in the face of increasingly alarming intelligence reports before both attacks, the causes of this inaction were starkly different. While the failure to prevent the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred in part because of the overarching effects of Groupthink, and the resulting overconfidence of diplomatic and military officials in existing defense preparations, we show in this book that the failure to prevent 9/11, like many U.S. decisions in the War on Terror, was a result of Polythink among and within key governmental decision-making branches.

Indeed, the authors of The 9/11 Commission Report (2004), tasked with exploring the national security failures that preceded the attack, summarize their findings as follows:

We learned of fault lines within our government—between foreign and domestic intelligence, and between and within agencies . . . We learned of the pervasive problems of managing and sharing information across a large and unwieldy government that had been built in a different era to confront different dangers . . . The massive departments and agencies [of the federal government] . . . must work together in new ways, so that all the instruments of national power can be combined. (xvi)

These symptoms are all hallmarks of the Polythink dynamic that we will explore in depth throughout this book (see Chapter 3 for the case study on Polythink prior to 9/11 and Chapters 4–7 for case studies of post-9/11 decisions on Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Syria, the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations, and ISIS).

Polythink is a general phenomenon; that is to say, it is a horizontal concept that can be applied to myriad realms. Indeed, Polythink is relevant to any group (not just decision units), including multiple groups within a decision unit. It has far-reaching implications for decision makers in the arenas of foreign policy, domestic policy, business, national security, and any other small-group decisions in individuals’ daily lives, from group projects in school to decisions about what to do on a Saturday night with friends. In this book, we show how Polythink is applied to the realms of national security and foreign policymaking, areas in which Polythink’s detrimental consequences can be particularly problematic and destructive. We also show how leaders can move from Destructive Polythink to Constructive Polythink (a dynamic we term “Productive Polythink”) and benefit from diverse points of view among group members.

The Groupthink-Polythink Continuum

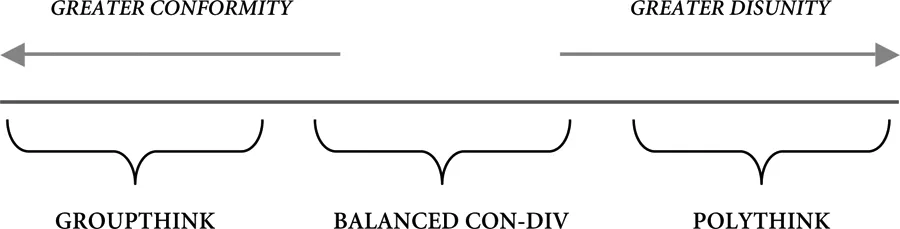

Polythink is essentially the opposite of Groupthink on a continuum of decision making from “completely cohesive” (Groupthink) to “completely fragmented” (Polythink). While Polythink is defined as a plurality of opinions, views, and perceptions among group members, Groupthink tends toward overwhelming conformity and unanimity. The divergence of opinions present in Polythink groups will often lead to myriad interpretations of reality, and policy prescriptions, making it difficult to formulate cohesive policies. Polythink can thus be seen as a mode of thinking that results from a highly disjointed group rather than a highly cohesive one. For example, some of the symptoms of Polythink are intragroup conflict and the existence of contradictory interests among group members (Mintz, Mishal, and Morag 2005), which may lead to a situation where it becomes virtually impossible for group members to reach a common interpretation of reality and common policy goals.

In the context of decision-unit dynamics, it is important to distinguish Polythink from the concept of “multiple advocacy,” in which decision makers “harness diversity of views and interests in the interest of rational policy making” (George 1972, 751). Rather, the multiple advocacy model can actually be construed as a type of structured Polythink process, in which the leader strategically capitalizes on the already existing Polythink dynamic to carefully lead and bring the divergent opinions of group members into a single, cohesive policy direction. Thus, whereas multiple advocacy is a type of Polythink, it is important to note that most forms, structures, and variants of Polythink are not multiple advocacy (see Chapter 2 for a detailed discussion of concepts related to the Polythink syndrome).

Both Polythink and Groupthink should also be considered as “pure” types. In real-world decision-making situations, there is rarely a case of pure or extreme Polythink or Groupthink. It is therefore more useful to think of these two concepts as extremes on a continuum in which “good” decision-making processes typically lie toward the middle and defective decision-making processes fall closer to one of two extremes—the group conformity of Groupthink or the group disunity of Polythink. The case of September 11 provides an illustration of this continuum. While both the Clinton and the Bush Administrations exhibited a mainly Polythink dynamic in their approach to national security and counter-terrorism policy in the pre-9/11 years, there was also a Groupthink-like nearly unanimous sentiment that an attack on the American homeland was impossible.

The Con-Div Dynamic

On the Groupthink-Polythink continuum, there is also a range in the middle in which neither Groupthink nor Polythink dominates. We call this area Con-Div, the range in which the convergence and divergence of group members’ viewpoints are more or less balanced and in equilibrium. In this situation, group members do not all share the same viewpoint and opinions, although they do share the general vision of the organization. In this scenario, the group is most likely to benefit from thorough yet productive decision-making processes that consider a multitude of options but ultimately reach some sort of consensus or agreement and execute well-formulated policies and actions. This is very different from either Groupthink or Polythink, which are both characterized by more extreme cohesion or dissent, respectively. Con-Div’s balanced nature should benefit group leaders as they can assess diverse inputs that are nonetheless reviewed in the context of overall consensus about vision and key goals.

FIGURE 1.1 Continuum of Group Decision-Making Dynamics

Symptoms and Conseque...