![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Roosevelt Court

The Critical Juncture from Consensus to Dissensus

The goal of this book is to explain consensus on the U.S. Supreme Court. A useful perspective from which to begin is to appreciate how the Court transitioned from a consensual to a dissensual body. We argue that this institutional transformation was the result of a series of internal and external changes to the judicial decision making process during the Roosevelt Court—a period roughly from 1937 to 1947 that was dominated by justices appointed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. These developments—occurring both on the Court and in the broader political environment—fundamentally altered the dynamic among the justices and forever changed the way they decided cases. The end result was the replacement of collective expression—once the long-standing norm—with individual behavior. This chapter thus serves to highlight the central question investigated throughout the book: Given all of the institutional pressures that point toward dissensus, how are the justices ever able to agree? In other words, how do we explain the puzzle of unanimity?

Here we seek to explain why and how the modern era of dissensus began. To do so, we highlight what Pierson (2004, 55) termed a “conjuncture”—a moment in time when “discrete elements or dimensions of politics” collide to produce a new, and often unintended, effect. Specifically, we identify a number of institutional developments that dramatically altered the extent to which consensus could be achieved in the Court’s decision making. We trace these trends by undertaking an extensive examination of the Roosevelt Court—the conjuncture, or moment in time, when its ability to achieve consensus changed.

Our investigation is based primarily on the private papers of Justices William O. Douglas and Harlan Fiske Stone, including memos sent between the justices, draft opinions, and other correspondence, which we use to determine the durable shifts in the Court’s decision making processes during these years. Our analysis shows that various institutional changes instituted both before and during the Roosevelt Court affected the Court’s decision making and brought about and entrenched a dissensus revolution in which individual expression went from virtual nonexistence to the norm.

While most scholars attribute the breakdown in the norm of consensus to Chief Justice Stone and his leadership style (e.g., Walker, Epstein, and Dixon 1988; cf. Haynie 1992), we break with them by highlighting the internal and external institutional developments that increased dissensus. More simply, to truly understand how the dissensus era arose we need to understand how the Court itself changed. By focusing merely on Stone’s personal style, one might make the argument that another chief, with a different style, could return the Court to its previous levels of consensus. We argue instead that the institutional changes implemented during the Roosevelt Court so fundamentally changed the Court’s operation that a return to the norm of consensus was virtually impossible.

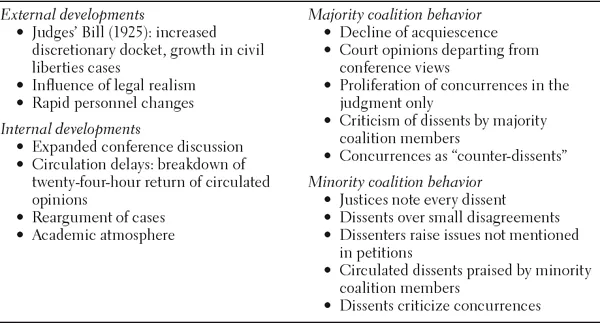

Table 1.1 shows the important institutional developments—internal and external, cause and effect—that occurred during the Roosevelt Court era. As we detail next, once on the dissensus path, there remained only a “critical juncture” to fundamentally alter the institution (Pierson 2004, 134–135). That moment arrived with the conjuncture of the external intellectual force of legal realism, the largely discretionary docket created by the Judiciary Act of 1925, popularly known as the “Judges’ Bill,” and the appointment of New Deal legal liberals, including the elevation of Stone to chief justice, who brought with them a more open, academic style. Under Stone, the justices developed new internal practices that undermined long-standing norms and ushered in the modern era of dissensus. Conference discussion was expanded, opinion writing and opinion circulation delays became common, and there were frequent calls to reargue contentious cases. In short, an academic atmosphere took hold.

TABLE 1.1

Institutional dissensus developments of the Roosevelt Court

External and internal developments on the Roosevelt Court had a dramatic, long-lasting effect on both majority and minority behavior. Justices writing majority opinions increasingly departed from the views of the Conference, the norm of acquiescence broke down, and more concurrences and dissents were issued than at any previous time in the Court’s history. Furthermore, majority opinions and concurrences were used to criticize dissents. Dissenters expressed small disagreements and discussed issues not raised in petitions, all the while praising each other for not acquiescing to the majority. The basic character of the decision making process was completely transformed.

The Roosevelt Court justices did not initiate these changes out of whole cloth. Specifically, developments toward the end of the consensus era foreshadowed the coming dissensus revolution. We propose that the consensus era on the Supreme Court began at the institution’s inception in 1789 and lasted into the Hughes Court, from 1931 to 1940. Interestingly, it began at the end of the eighteenth century in a decidedly individualistic manner, with the earliest justices issuing their opinions seriatim (i.e., individually in each case), and ended at the close of the nineteenth century with a resurgence of individual expression, presaging the dissensus era to come. However, it is the period in between that largely defines what we term the consensus era. From the Marshall Court to the end of the nineteenth century, Supreme Court decision making was dominated by the institutional norm of consensus, including a desire for unanimity and a distaste for dissent and individual expression. Decision making took place orally; the justices largely acquiesced and said nothing publicly if they disagreed with the majority; institutional opinions were often delivered by the chief justice and not circulated to the other members of the Court for input (as they are today); and the practice of circuit riding provided justices with a regular outlet for individual expression. As Epstein, Segal, and Spaeth (2001) showed in their examination of the docket books of Chief Justice Waite, justices commonly muted disagreements expressed at Conference and instead joined the majority opinion. As a result, between 1801 and 1940, the Court handed down unanimous decisions approximately 90 percent of the time, if not more often (Epstein et al. 2007).

At the end of the nineteenth century, however, a number of institutional developments occurred that placed the Court on a path toward increasing dissensus. During the Fuller Court (1888–1910), the courts of appeals were created and the Supreme Court gained limited discretionary review over its docket, thereby allowing it to choose more important, and often more difficult, cases to decide. Also, circuit riding, the outlet for individual expression, was abolished. Now draft opinions began to be circulated to each member of the Court, and for the first time the justices were able to thoughtfully critique a written opinion before it was issued. These institutional developments helped promote dissensus and presaged the coming, modern era of increased discretion over dockets, the influence of legal realism, and further changes to the decision making process.

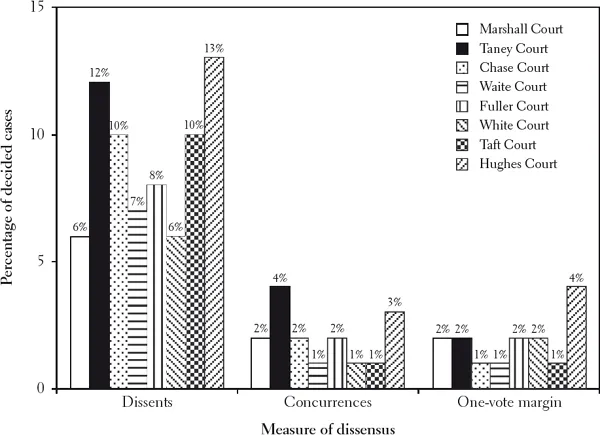

Figure 1.1 compares indicators of dissensus across consensus-era Courts. Although the transition from the relatively consensual Fuller and White Courts to the more divided Taft and Hughes Courts is evident from the percentages of dissents, concurrences, and cases decided by a one-vote margin, the levels of dissensus under Hughes were still similar to those under Taney. Thus, while dissensus was seemingly on the rise, there was no reason to believe that the Court would not soon return to more consensual levels. And yet, as we demonstrate, the justices of the Roosevelt Court so changed the way the Court functioned that even they appear relatively consensual compared to their successors.

Figure 1.1. Measures of dissensus in consensus-era courts

SOURCE: Data from Lee Epstein, Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold Spaeth, and Thomas G. Walker, The Supreme Court Compendium: Data, Decisions and Developments, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007).

Revisiting the Roosevelt Court

President Roosevelt made nine appointments to the Supreme Court, including the elevation of Stone to chief justice. Hugo Black, Stanley Reed, Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas, Frank Murphy, James Byrnes, Robert Jackson, and Wiley Rutledge joined Stone and the other holdovers to make up what C. Herman Pritchett (1948) termed “the Roosevelt Court.” And while it is conventional to name Courts after their chiefs, we consider the justices who served with Stone to be members of the Roosevelt Court in this discussion, for it is this set of justices who transformed the Court from a largely consensual body into an institution where individual expression was common.

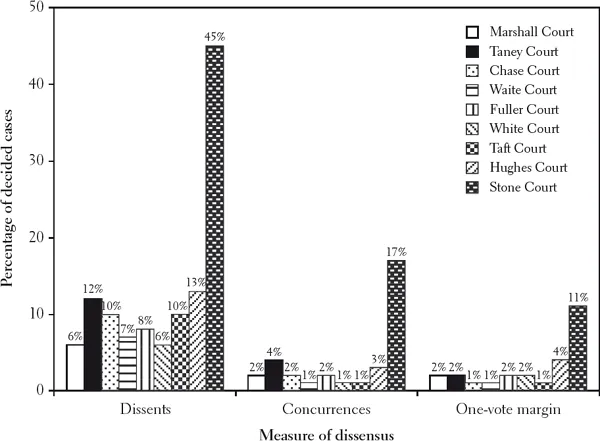

Figure 1.2 illustrates the dramatic sea change in nonconsensual behavior under Chief Justice Stone. While levels of dissensus increased during the Taft and Hughes Courts, there can be little doubt that the Roosevelt Court justices transformed the institution during Stone’s tenure as chief (Caldeira and Zorn 1998; Halpern and Vines 1977; Mason 1956; Murphy 1964; Pritchett 1948; Walker, Epstein, and Dixon 1988). Nearly half of all Stone Court decisions had at least one dissent, nearly one in five contained a concurrence, and one in ten was decided by a single vote. No previous group of justices had ever come remotely close to these levels of public discord.

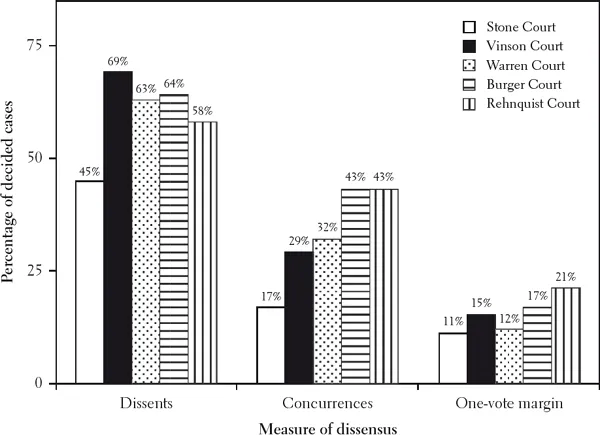

Figure 1.3 further shows that the dissensus trend ushered in by the justices of the Roosevelt Court was anything but an aberration. As new justices joined holdovers such as Black and Douglas, they adopted the dissensus norms begun by their predecessors. Dissent rates regularly reached 60 percent, concurrence rates continued to climb, to 40 percent, and cases decided by a one-vote margin reached 20 percent. Although the personal predilections of the holdovers certainly contributed to the growth of dissensus over time, a number of important institutional changes that occurred during the Roosevelt Court continued to be influential on future Courts and helped to entrench the norm of dissensus, which continues to this day.

Figure 1.2. Comparing the Stone Court to its predecessors: Measures of dissensus

SOURCE: Data from Lee Epstein, Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold Spaeth, and Thomas G. Walker, The Supreme Court Compendium: Data, Decisions and Developments, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007).

Figure 1.3. Comparing the Stone Court to its successors: Measures of dissensus

SOURCE: Data from Lee Epstein, Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold Spaeth, and Thomas G. Walker, The Supreme Court Compendium: Data, Decisions and Developments, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007).

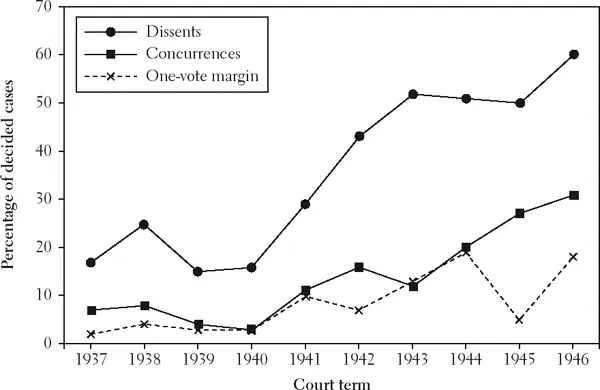

Once the justices of the Roosevelt Court set out on the dissensus path, their practices and behavior only increased the amount of divisiveness over time. Figure 1.4 shows that cases with dissents reached an all-time high of 52 percent in 1943, only to be topped at 60 percent in 1946. This upward trend continued until 80 percent of the decisions handed down in 1952 contained a dissent—a record that still stands. Dissents were common among Roosevelt Court justices in landmark cases. These included Betts v. Brady (1942), in which Black, Douglas, and Murphy disagreed with the majority opinion denying a right to counsel for indigent defendants; West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette (1943), in which Frankfurter, Reed, and Owen Roberts dissented from a ruling protecting students from being forced to salute the American flag and recite the Pledge of Allegiance in public schools; and Korematsu v. United States (1944), in which Roberts, Murphy, and Jackson opposed the Court’s decision allowing the government to intern Japanese Americans during World War II.

Figure 1.4 also reveals an increase in the percentage of cases with a concurrence, which climbed to another record of 31 percent in 1946. Eventually, the justices issued concurrences in 57 percent of cases by the 1970 term—an as yet unsurpassed high-water mark. Even some of the landmark cases decided unanimously contained concurrences. For example, both Stone and Jackson concurred in Skinner v. Oklahoma (1942), which invalidated state criminal sterilization laws; and Douglas, Murphy, and Rutledge each issued separate concurrences in the World War II Japanese-American curfew case Hirabayashi v. United States (1943).

Figure 1.4. Measures of dissensus on the Roosevelt Court, 1937–1946 SOURCE: Data from Lee Epstein, Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold Spaeth, and Thomas G. Walker, The Supreme Court Compendium: Data, Decisions and Developments, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007).

Finally, Figure 1.4 shows that the percentage of cases decided by a one-vote margin reached an apex of 19 percent in 1944. For example, both the Free Exercise tax-solicitation case Murdock v. Pennsylvania (1943) and the Commerce Clause insurance case United States v. Southeastern Underwriters Assn. (1944) were decided by a single vote.1

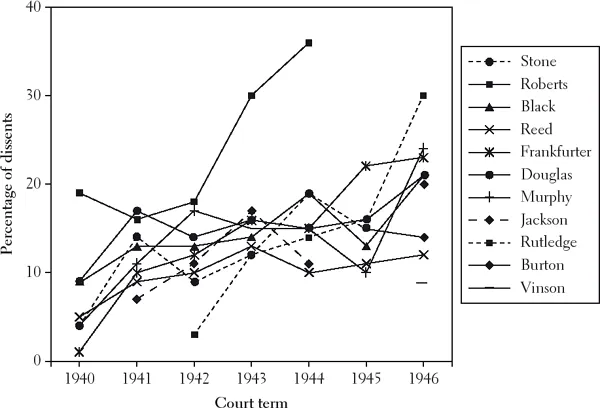

It is important to note that the Court’s disagreements were not simply the product of a few justices. Figure 1.5 illustrates how each justice on the Roosevelt Court increased his level of dissenting votes over time. For example, Stone’s dissents increased from 4 percent of cases in 1940 to 19 percent in 1944; Roberts’s, from 19 percent in 1940 to 36 percent in his final year on the bench; Black’s, from 9 percent in 1940 to 21 percent in 1946; Reed’s, from 5 percent in 1940 to 12 percent in 1946; Frankfurter’s, from 1 percent in 1940 to 23 percent by 1946; Douglas’s, from 9 percent in 1940 to 21 percent in 1946; Jackson’s, from 7 percent in 1941 to 20 percent in 1946; and Rutledge’s, from only 3 percent in 1942 to a striking 30 percent in 1946. As the figure shows, the dissensus trend was plainly a collective enterprise.

Figure 1.5. Dissenting behavior of the Roosevelt Court justices, 1940–1946 SOURCE: Data from Lee Epstein, Jeffrey A. Segal, Harold Spaeth, and Thomas G. Walker, The Supreme Court Compendium: Data, Decisions and Developments, 4th ed. (Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2007).

Still, despite the unprecedented amount of dissensus occurring on the Roosevelt Court, the justices reached consensus half of the time and in a number of important cases. They spoke in a single voice in the “fighting words” case Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942), the World War II “enemy combatant” case Ex parte Quirin (1942), and the Commerce Clause agricultural case Wickard v. Filburn (1942). These decisions illustrate that even on a...