![]()

PART I

Prelude to the Sixties: Youth Unrest and Resistance to Postwar “National Identity”

![]()

1

Conflicting Interpretations of Mexico’s “Economic Miracle”

Beginning in 1938 and continuing during the presidential administrations of Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940–1946), Miguel Alemán (1946–1952), and Adolfo Ruiz Cortines (1952–1958), Mexico experienced a period of dramatic changes. The new Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI) economic model was created and ideologically promoted under revolutionary nationalism. As understood throughout the continent, the idea of ISI was that, by investing in its own national industries, Latin America would minimize the historical dependency on European and North American manufacturing and agricultural goods and, thus, become more integrated and self-sufficient, particularly, during difficult worldwide economic recessions.1 With this goal in mind, the patriotic banner of “national unity” served as the impetus for ISI, whose effect was felt primarily in the nation’s capital. In time, these economic changes came to be equated with rapid urban industrialization, an influx of entrepreneurs and technocrats into the government, the centralization of state power, and a more harmonious relationship with the private sector.2

This period was commonly hailed as Mexico’s “economic miracle.” It was widely reported, for example, that between 1940 and 1966, the Mexican GDP grew 368 percent. In addition, the press, governmental reports, and scholars also noted that the average annual growth-rate of GDP for the same period was larger than 6 percent.3 Other indications of this tremendous growth included significant advances in manufacturing, an unprecedented low inflation, and a steady foreign exchange rate.4 Furthermore, the economic miracle represented a moment when a number of important technological advances in the energy, communications, and transportation systems were realized, and increases in production, tourism, and the availability of consumer goods stimulated mass consumption for a burgeoning middle class. This was especially true following the presidential administration of Ávila Camacho, when dozens of new industries dramatically transformed the economic and social landscapes of Mexico.5

However, a closer look at other forms of statistical data reveals that this economic boom came with a high price. For example, while this period saw substantial economic growth as measured in GDP, dependency on foreign capital in the form of direct foreign investment (mostly from the United States) grew more than 700 percent between 1940 and 1957, primarily because of the state’s failure to finance itself from domestic resources.6 As a result of this investment, the economic and cultural roles of the United States in Mexico during this period grew significantly important. U.S. government officials, advertising agencies, and business executives regained ownership of production properties and dominated bilateral trade and high technology.7 Moreover, they brought with them new capitalists beliefs that primarily benefited the rising middle class in the urban sector as represented in the celebrations of upward social mobility, material prosperity, and what historian Julio Moreno calls “a form of democracy through consumption.”8 Concurrently, the economic miracle did not necessarily benefit all sectors of society equally. Economist Roger Hansen noted, for example, that economic growth during this period did not imply a reduction of social and economic inequalities. He concluded, in fact, that the cost of living index for Mexico City’s working class increased significantly from 21.3 in 1940 to 75.3 in 1950 (1954=100). Yet real wages plummeted by as much as 30 percent between 1940 and 1950.9 The situation did not improve during the next decade for the bottom 30 percent of families, as they experienced a decline in their monthly incomes from an average monthly salary of 302 pesos in 1950 to 241 in 1963.10 The top 30 percent of families, in contrast, saw an average increase in their monthly incomes from 1,132 pesos in 1950 to 2,156 in 1963.11

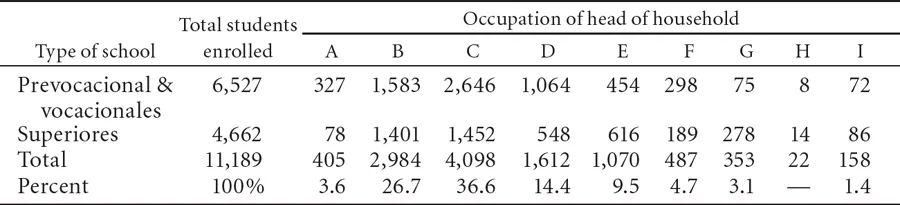

Economic disparities had an important impact on the composition of schools. More than 80 percent of politécnicos (students enrolled in the National Polytechnic Institute, IPN) during the late 1930s came from parents of the lower class, particularly the working, public, and peasant sectors (see Table 1.1). Only a small fraction of them (4.7 percent) came from households in which their parents held a professional career.12 Unfortunately there are no reliable statistics on the social background of politécnicos during the 1940s and early 1950s. Jorge “Oso” Oceguera (head of the cheerleading team of the IPN, 1950–1957) remembered during an interview, “[T]he fact that we were students certainly put us in a privileged position. But in reality, the overwhelming majority of politécnicos were from the working class or what could broadly be described as a lower middle class on the verge of upward social mobility.”13

TABLE 1.1. Social Background of Politécnicos, 1936

Key: A, Domestic workers, etc.; B, Workers, peasants, and artisans; C, Government employees, including members of the police and the military, etc.; D, Small commerce and agricultural workers; E, Female housekeepers; F, Shopkeepers and small entrepeneurs; G, Self-sufficient students; H, Students who depend on Boarding Schools; I, Not classified.

Source: Data from IPN, 50 años, 63.

Nicandro Mendoza (principal leader of the 1956 student protest) gave a similar description:

Prior to the [1956] strike, the majority of us came from humble origins. This was evident in the clothes we wore, in the neighborhoods where we lived, and especially, in the nature of the demands that we raised during our student protests. The majority of students enrolled in the Politécnico came from parents of the lower classes. Many politécnicos certainly witnessed a gradual improvement in their lives during the 1940s and 1950s, but judging from the frustration expressed in many of the political rallies organized during these two decades, you could conclude that a large majority of students felt that they had been excluded from the economic boom.14

The socioeconomic circumstances of the politécnicos differed from the overwhelming majority of universitarios (students enrolled at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM) during the growth of Mexico’s economic boom. The first census taken at UNAM in 1949, for example, indicated that from a total of twenty-three thousand students, 29 percent came from parents that were described as comerciantes (merchants), 20.64 percent as empleados (public employees), and 10.58 percent as profesionistas (professionals). In other words, unlike the majority of working-class politécnicos, a total of 70 percent of all students enrolled at UNAM in the late 1940s could be broadly defined as members of the middle class. The remaining 30 percent were from the lower- and upper-class sectors.15 Historian David E. Lorey noted that little had changed over a decade later.16

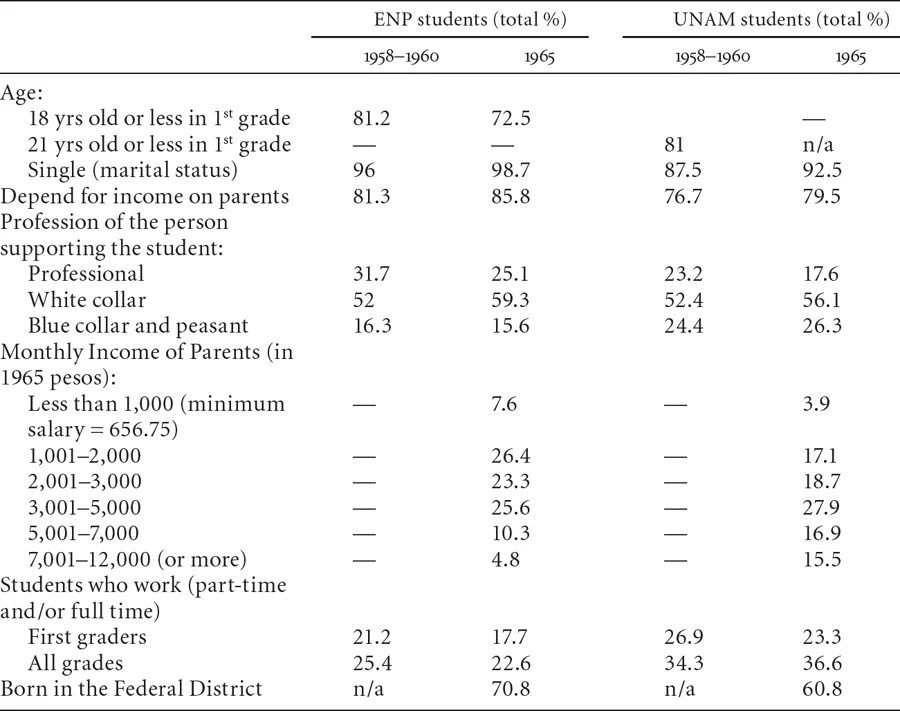

TABLE 1.2. Social Description of Universitarios, 1958–1965

Source: Data from Covo, “La composición social.”

Data compiled from a study by Milena Covo (see Table 1.2) supports Lorey’s major findings. It also offers a more detailed description of the social composition of most universitarios during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Nearly all students enrolled at UNAM during this period were between the ages of eighteen and twenty-five. At least one-third of all universitarios were born outside the Federal District. Only a small fraction of the total number of students were married. By and large, their education was paid for by their parents, who generally held a professional or white-collar job.17 An average of one-fifth of all universitarios held a part-time or a full-time job to supplement their income. In short, as Lorey similarly noted in his study, a significant number of students enrolled at UNAM came from the middle- and upper-class sectors, which witnessed the greatest benefits of the economic boom.

The class distinctions between politécnicos and universitarios would influence the distinct political trajectories that these two groups of students would take during the 1940s and 1950s. Because the postrevolutionary state proceeded to transform UNAM into the most important educational institution in Mexico’s pursuit of modern industrial capitalism, universitarios overwhelmingly fared much better as a result of the restructuring of the economic and political systems during this period than did the politécnicos. For the latter, the “shift to the Right” in politics and the state projects of “modernization” and “national unity” meant a gradual abandonment of the cardenista policies, including what they deemed as an “attack” on popular education and a deterioration of their schools. For universitarios, on the other hand, these two decades brought unprecedented economic opportunities celebrated with the creation of Ciudad Universitaria and a new attitude of middle-class consumption. For both, this period of extraordinary economic expansion also marked the rise of a unique environment of corporatism and nationalist anticommunism, as well as an unprecedented growth in student population. A further examination of the impact these socioeconomic, demographic, and political changes had on the student population lays the groundwork for the so-called student problem that emerged during the long sixties and the perceived need on the part of authorities to control it. But first, a brief historical sketch of the founding of UNAM and the IPN and the successful efforts to extend state corporatism into the domains of these major centers of higher education is in order.

Conflicting Origins of UNAM and the Politécnico

UNAM has its roots in the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico, which was founded in 1551 and officially inaugurated in 1553 as the oldest North American university in the Western tradition. For two centuries it would serve as one of the principal institutions of colonial culture and authority. Its time-honored elite status repeatedly expressed itself in a conservatism, a resistance to change from without, and an uneasy, see-saw relationship with the state. For example, in 1821 the university refused to accept the new independent nation, and it sheltered those who fought in favor of retaining colonial rule. The conservative university was viewed as a threat to the new nation by influential liberals like José María Luis Mora, who declared it “useless, pernicious, and irreformable.”18 Following the war of independence, the university was forced to close its doors several times.19

After closing the university in 1867, President Benito Juárez opened the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (National Preparatory School, or ENP) in the colonial building of San Ildefonso. Located at the center of what became known as the barrio estudiantil (student neighborhood), the ENP served as the most prestigious institution since its creation in 1867 until September of 1910, when the National University reopened its doors as part of the centennial celebration of independence. Two months later, the Mexican Revolution erupted, and once again the university served as a refuge for those who found themselves in opposition to the insurgents.20 Tension between the university and the state continued to grow following the violent phase of the revolution (1910–1917). The subordination of the university to the Ministry of Public Education (SEP) in 1923, and the creation of the secundarias (Secondary Schools) two years later, further worsened the relationship.21 The tension came to a head in a 1929 student protest that resulted in important concessions. The protest forced the state to grant the university its autonomy; it gave the school the legal rights to administer its resources, make academic decisions, and appoint its own administrators. By incorporating the Federación Estudiantil Universitaria (University Student Federation, FEU) into the University Council, students were represented as a unified body.22

Relations between the university and the state would turn bitter once again in the early 1930s during a debate over the role that socialist ideas should have in the schools. Student strikers had raised the issue of a specifically socialist approach to education during a 1929 strike, and the 1933 University Congress in Puebla provided a forum for opposing sides on this issue to meet.23 One camp of students and school authorities was represented by Vicente Lombardo Toledano, a teacher, union leader, political activist, and a director of the ENP at the time. While praising the university for its “affirmation of spiritual values and human dignity,” Lombardo Toledano believed that only a radical redistribution of wealth on the part of the state and a socialist educational campaign carried out with the help of universitarios could incorporate the poor into the revolutionary project to create a truly just society.24 Strongly disagreeing with this position was a second and larger faction. It was composed of old liberals, conservatives with close affiliations to the church, and leftists, broadly represented by the man of letters and former university rector Antonio Caso. For Caso and his followers, academic freedom could be guaranteed only with institutional neutrality and, thus, a legally sanctioned socialist pedagogy placed this in jeopardy. For those who agreed with Caso, politics had no place inside the schools. Rather, they envisioned the universities as cultural communities exclusively concerned with research and teaching.25 Key players inside the university—including José Vasconcelos (rector of the university in 1920 and first Secretary of Public Education, 1920–1925), Rodolfo Brito Foucher (director of the Law School), and Alejandro Gómez Arias (leader of the 1929 studen...