![]()

PART I

ENVIRONMENT AND HISTORY

As is true anywhere in the world, there is much about the human ecology of Samosir, north Sumatra, that does not meet the eye. As soon as one attempts to describe what does, one is forced to refer to that which does not. The first chapter concerns deceptive appearances. I describe the place of the village of Huta Ginjang, the environment, and the area’s demography. I then give an account of Dutch-induced agricultural change, the first of several indictments of colonial policies for the Samosir microcosm of the larger Dutch experiment in what is now Indonesia.

The second chapter expands on the historical background of the area and on the changes imposed by the Dutch and those resulting from their influence, particularly regarding monetization.

![]()

Chapter 1

Deceptive Appearances: Environment, Demography, and Agricultural Change

The hamlet cluster on which this study is based is called Huta Ginjang, ‘top village.’ It lies some 3 degrees north of the Equator, perched about two miles up the north side of Pusuk Buhit, ‘Mount Navel,’ a dormant volcano that connects Samosir ‘island’ (actually a vast peninsula in Lake Toba) to the body of Sumatra (see Map 2). The nearly 600 inhabitants of the village share a single spring for all water they use domestically.

Generally the climate of Sumatra is characterized as being of “equatorial monsoon” type. Samosir has the most pronounced dry season of all Sumatra, since it lies in a highland crater, from which the surrounding landmass slopes down to the encircling seas (see Map 1). In the dry season, the winds blow in, often with incredible and repeated gusts, from the southwest and from the west. They may start as early as April and continue well into October. Beginning in July, the wind often blows constantly, day and night, at some 50 miles an hour, with gusts up to 80 miles an hour.

At times one gazes out over the parched expanse of the northern half of Samosir ‘island’ and imagines that if only its clayey whiteness were a dark tree-green, the misty clouds that hover around the lake at the edges of the crater would somehow yield a bounteous wet rain rather than the mistlike drizzle that never penetrates the ground more than an eighth of an inch. After a three-week blow, the wind lets up and gives way to scorching hot, clear days with only a rare puff of cloud in sight. Then, just as it seems that enough of these rare puffs are appearing to give rise to a real thunderhead or two, the wind starts up again, and what had seemed to be clouds reveal themselves to have been apparitions dissipating into the mist-bearing collar that sits, apparently immobile, hugging the upper edges of the lake crater in uncanny defiance of the wind. The sky turns white, and another three-week blow begins. So it goes, alternately, from May through September, primarily between June and August.

Map 2. Mount Pusuk Buhit, with Sagala and Limbong Valleys and Huta Ginjang.

TABLE 1.1

Monthly Variation of Rainfall (mm)

The seasonal oscillation of rainfall recorded between 1922 and 1928 by the Dutch administrators at Pangururan, the town at the point where the mountain and island are joined, can be seen in Table 1.1. Whereas in the dry season, during the stretches of overcast gale winds, the sun often does not break through the cloud cover, much of the “rainy season” is actually sunny for most of the morning and afternoon, except for an hour’s downpour toward the evening. Parts of the rainy season are, then, much hotter than parts of the dry season.

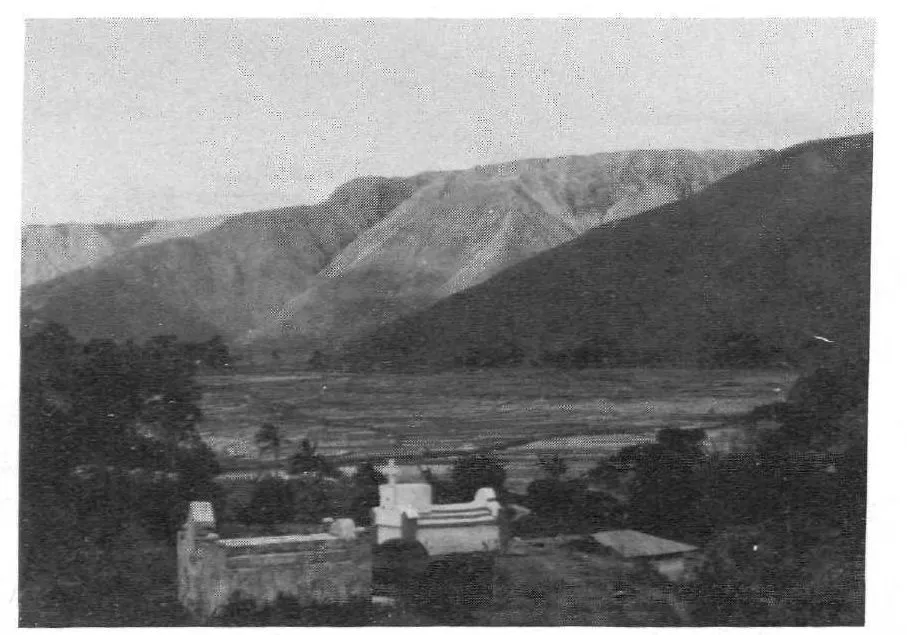

Mt. Pusuk Buhit in the early dry season, from the north. Huta Ginjang lies halfway up on the right. Farmers’ fields extend beyond far upper left puff of smoke.

From its vantage point halfway up the mountain, Huta Ginjang overlooks the north end of Samosir and, to the west, the raised, stream-fed bowl of Sagala Valley (invisible from the lake or from Samosir Peninsula), that has one bottleneck egress lying between the mountain and the lake-crater wall that encircles both. In 1933, J. C. Vergouwen referred to this area as the “out-of-the-way mountain territory of Sagala.”5 Numerous other isolated, well-watered valleys nestle in the crevices of the vast crater enclosing the lake. What makes for Sagala’s apparent isolation is that it is not a thoroughfare and is divided from the lake by a long-solidified shoulder of the mountain. To the south, it is cut off from its proper extension, Limbong Valley, by another shoulder of Pusuk Buhit. (Two of the grandsons of the first man, Si Raja Batak, were named Limbong Mulana and Sagala Raja.)

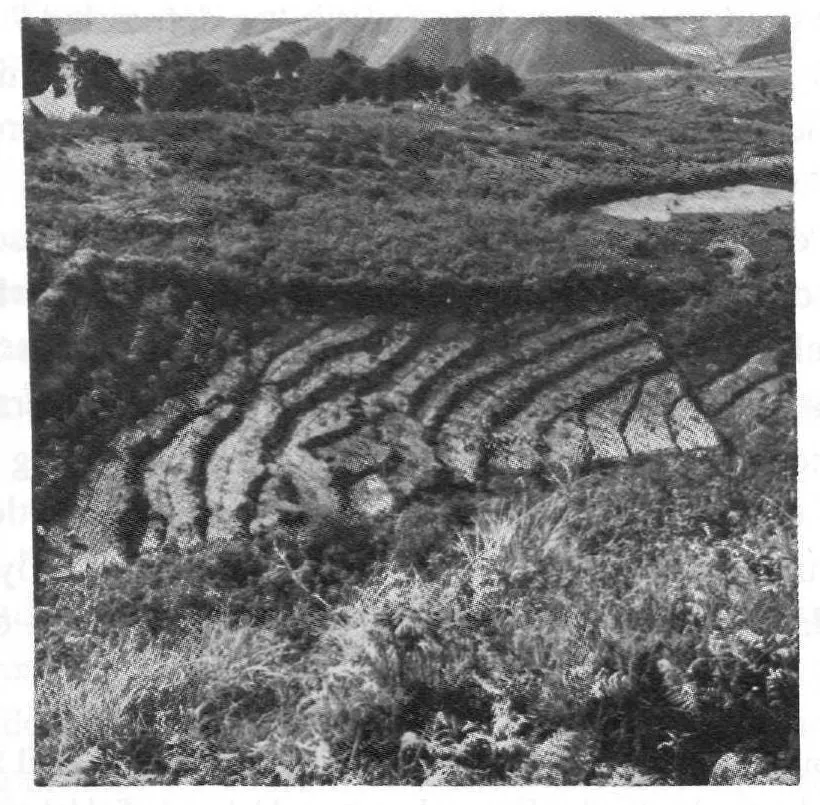

Sagala Valley from the north. A school roof visible at right, below concrete tombs.

Pusuk Buhit seen from the northwest, in the early dry season, June 1978.

Hundreds of tourists each year pass within 5 kilometers of the village on “round-the-island” diesel steamer tours and do not see it. Its existence is signaled by what appears to be a tiny clump of trees in the vast, seemingly barren and uninhabitable expanse of brush and savannah that cloaks the mountain. A keen eye may note the darker brown of cultivated areas of level stone terraces, an occasional puff of smoke from some distant shoulder (the sign of a raging savannah fire), or the deeper green that sets off ripening rice in scattered, minimally terraced patches high on the mountain. But even the ubiquitous terraces of the mountain’s middle and lower reaches are normally hidden from sight by brush and Imperata grass cover, at least until a boat reaches the canal at Pangururan and passes through the land bridge that connects the mountain to the Samosir peninsula. There, the terraces covering the lower half (as high as the eye can see) are in almost constant use, and at seasons when most are planted, the mountainside resembles a wall of stone.

Water and Settlement Patterns

Sianjurmula-mula, the purported site of the original Batak hamlet and home of the first man, Si Raja Batak, is at the southern end of Sagala Valley, at the foot of the spur connecting the mountain to the high plateau that extends west from the lip of the crater. It was on our way to visit it that my wife, Hedy, and I happened on the village of Huta Ginjang.

Ultimately, the existence of this village may be attributed to the fortuitous occurrence of a spring on the northwest flank of the mountain. Water is carried to the houses throughout the year by women and girls, who imitate the carrying of buckets from the time they learn to walk. Villagers bathe, wash clothes, and get water for household use at a divided bathing place with three pipes below a small holding tank. Two pipes go into the women’s compartment and one into the men’s, since some women and girls need water for domestic purposes while others are bathing or washing clothes. No water is piped for household use to any of the hamlets because many are afraid that the flow would not be sufficient to meet the needs of washing, etc., and they therefore refuse to invest in pipe. In the dry season the downstream bed of the brook is parched for months, because all the “excess” water is diverted for irrigation.

The area on the southern flank of the mountain contrasts with Huta Ginjang on its north. It was never even settled in the traditional walled-hamlet pattern, because of the lack of year-round springs. Some 200 scattered houses built there in the recent past have rectangular concrete water tanks with a capacity of 2,000 to 3,000 gallons of water fed by gutters that run around the edge of the roofs.

Until this century, Sumatra’s coastal lowlands had much lower population densities than the interior highlands. In 1824, on a journey to what is now the site of the regional capital, Tarutung, the missionaries Burton and Ward, after scaling the escarpment on the Indian Ocean side of Sumatra, were astounded to find a long, broad valley of wet-rice terraces between grass-covered hills.

Why were population densities greater in the highlands? In addition to Batak fear that the spirits thought to cause tropical diseases are more prevalent in the lowland areas and to their dislike of the heat and humidity of those areas, it may be that over the course of many centuries the denizens of the coastal areas grew averse to their exposure to the levying of taxes and demands of fealty by coastal/riverine patrols emanating from Srivijaya and other maritime powers that controlled the sea-lanes. A trend to move upland, away from the coast, may have developed. Lower temperatures and less rain in the mountains would also have favored the deforestation so necessary to high population densities, because forest would not retake clearings as quickly as under moister conditions. In particular, the pronounced dry season of the Samosir region would have inhibited regrowth of secondary forest, and lake fish would have helped assure settlers a reliable source of protein. At the same time, the perennial springs could be exploited for irrigating rice.

Dutch data on Samosir population, based on the counts of village headmen who were expected to collect and pay taxes for those under their jurisdiction, might be underreported. In 1913 there were 78,169 Samosirese (40,187 males and 37,982 females) in 2,236 hamlets (Middendorp 1913:13). By 1931, the number had risen to 96,267. The chief administrator (Dutch, Controleur) at the time remarked that “emigration is hardly taking place” (van Bemmelen 1931:13-14). Although much out-migration has since occurred, the Indonesian government reported the 1980 population as 126,696. These and other data are shown in terms of density in Table 1.2.6

The density of over 500 persons per square mile far exceeds the densities reported for forest shifting cultivators (Conklin [1957:10] reports a range of 65-91 for the Hanunóo; Freeman [1970:133], a range of 52-65 for the Iban; Dove [1985:381], 30 persons per square mile for the Kantu’; Hanks [1972:57], an average of 31 persons per square mile based on six cases). However, from the area of fallow terraces one sees in Samosir, the population may have been even higher at times in the precolonial past. This would explain the exaggerated claim, often made by educated, city Batak, that Samosir, or their lakeregion homeland generally, has been deserted by all but the very old and the very young. The notion of near-total abandonment of the Toba homeland has a strong and pernicious hold, perhaps because quite a number of young men become emigrants for varying lengths of time. Yet, as will be shown, in spite of adverse climatic and other environmental factors, the people maintain a firm foothold and finance a variety of means of more or less successful outmigration in agriculture, trade, and education.

TABLE 1.2

Density of Samosir’s Population and Increments per Year

Illusions of Timelessness in the Landscape

Most accounts of Batak agriculture highlight the feats of engineering of their irrigation systems, but mention of the equally impressive, rain-dependent, dry-field terracing, so much in evidence in the Samosir area, is rare. All around Mount Pusuk Buhit and in the valleys on the west, north, and east sides of the lake, as on the east side of Samosir, the earth on which terraces were built appears to be more than half stone, much of it boulders. A tremendous amount of effort and skill was required to transform the terrain into the humanized landscape it now presents to the eye.

A farmer (bent over, 6 terraces up from the bottom), his son (to the right, 7 up), and daughter (center, 9 up) prepare an irrigable field for dry-season bulb planting.

Five foot-high terraces in a non-irrigable mulched garlic field. Cassava is growing on the edges of the walls. Man and wife visible in lower left corner. Proximity to the hamlets inhibits burning in this area, hence the brush. Foreground: Imperata.

Contemporary villagers remain expert rock-wall builders. Steepness of slope never appears to prevent terracing, either for irrigated fields or for dry. In long-fallow areas, walls are completely dismantled when a field is reworked. They are also built around some fields next to cattle paths, and in the past walls were built between certain clan areas. Running up the western side of Mount Pusuk Buhit, from the point at which the Sagala and Limbong Valleys come closest to joining, is a wall of boulders, surrounded on both sides by deep drainage ditches. Its purpose was said to have been not to keep cattle in but to prevent attacks by horse-mounted ride...