![]()

ONE

Origin Time

Perhaps more than any other geographical element, rivers have a way of provoking the imagination. Their constant motion suggests a living being; their distant origins spark the romantic itch for discovery; and their dual roles as benefactors and destroyers provide a metaphor for the gods’ fickle friendship with humanity. Just as the ancient Egyptians looked on the Nile as the source of both life and suffering, so too, the rough-hewn people of Tabasco could read in their rivers a lesson regarding the enigmas of their worldly existence.1 Those same meandering bodies also offer something more mundane, some fiber common to the social world that emerges along their banks. Riverscapes provide national metaphors, with the august Hudson Valley symbolizing a providential role for the United States, the winding Volga summoning up the peasant essence of Russia, or the bustling Thames reflecting London’s imperial economic status.2 But the myth power of riverscapes holds doubly true for Tabasco. Unlike all other parts of Mexico, the province is shot through with a bewildering network of streams and swampland that makes water excess, not aridity, the principal geographical challenge to human settlement. The southern Gulf coastal waterways define their surroundings, and those who choose to live and die by their caprice have always been, and will always be, river people.

Most Tabascan waters originate along the northern and western ridges of the Chiapan-Guatemalan highlands. Even today, the headlands of these rivers constitute a unique area for Mesoamerica: mountainous, well watered, lushly vegetated, and thinly populated next to the dense concentrations of Mexico City or the coastal capitals of the Yucatán peninsula. Few people not born in this region ever visit it in any serious way, save to see the magnificent archaeological sites . . . most of them discovered by peasants in search of land for the slash-and-burn agriculture that has been the basis of life here from time beyond memory. They were higher once, these mountains pushed up from the sea by the collision of tectonic plates deep within the earth. In fact, Tabasco itself only exists because eons of erosion have carried down uncountable millions of tons of soil and mineral from the uplands and deposited them on an alluvial plain.

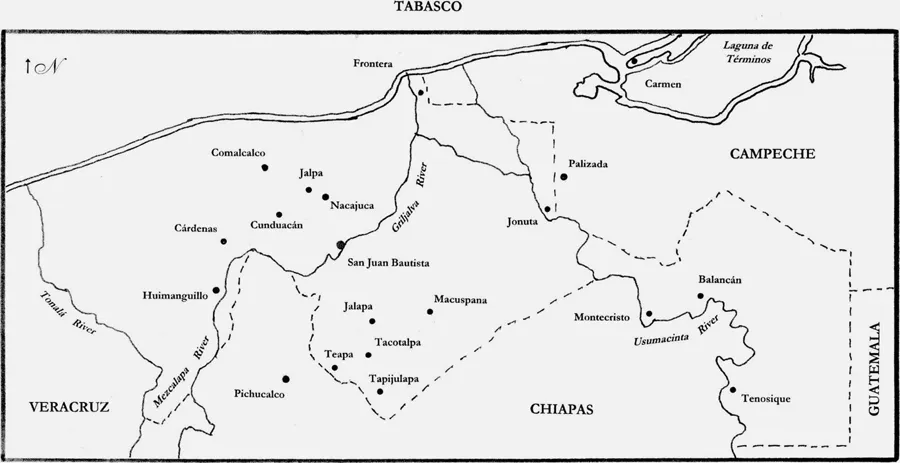

Lands to the south of present-day Tuxtla Gutiérrez empty into streams leading to the Pacific coast. But drainage north of that point feeds into Tabasco’s westernmost waterway, the Tonalá (“place of heat”), which marks the current-day boundary with the state of Veracruz. From these same points, but moving northeastward, issues the Mezcalapa (“river of magueys”).3 It originates in a remote southern point to which few people ever travel. There stands Malpasito, an Early Postclassical Period (roughly 900–1200) site of the Zoque peoples, built high on a mountainside and noted for its exemplary prehistoric ball court and sweat bath. From their highland vantage point, the pre-Columbian Zoques mediated overland trade passing between the Caribbean and Pacific coasts. The Mezcalapa has an unusual history that joins natural caprice with human interest and initiative. Prior to the late seventeenth century, the river ran due north, passing successively through a string of towns from Huimanguillo to Comalcalco, past fields of herons, cranes, and egrets, before emptying into the swerving shores and bending bays of the Gulf of Mexico, near the current-day town of Paraíso, at the Tupilco bar. However, the natural levees of the river were low formations of soft mud and easily given to meanderings, breaks, deluges, and redirections.4 One of the most important of these happened in 1675, when the east banks gave way just south of Huimanguillo (“place of the great cacique”), causing the entire river to shift eastward into the Grijalva. Far from being alarmed, Spanish settlers dug canals in order to accelerate the process: by turning the Mezcalapa into a Grijalva tributary, they robbed pirates of an easy entry into central Tabasco, forcing both merchants and raiders alike to traverse the more easily fortified Grijalva. The former course of the Mezcalapa still exists, mainly in the form of a low area with occasional wetland pockets, and is known, appropriately enough, as Río Seco, or “dry river.”5 Such abrupt changes in major waterways may well have played a role in the abandonment of some of the earliest pre-Columbian settlements, which depended on rivers for both drinking water and transportation.

Figure 1. Map of Tabasco, with principal cities, towns, and rivers. By Terry Rugeley.

Due south of the capital city of San Juan Bautista de Villahermosa a series of rivers descend from the Chiapas border: originating from a broad catchment in the Guatemalan highlands, the Teapa (originally, “Teapan,” or “river of rocks”), the Tacotalpa (“place of uneven surface”), and the Puyacatengo (“on salt water banks”), all flow northward, where they combine into the Grijalva, named for the first European to explore these parts.6 This great waterway originates in Guatemala’s Huehuetenango district, flows northward through Chiapas, at which point multiple tributaries combine to form the Grijalva proper. It passes to the right of Villahermosa and continues north, eventually joins with the east-lying Usumacinta, and empties into the Gulf just north of modern-day Frontera. Collectively, the Grijalva-Usumacinta waterway constitutes the fifth-largest river system in Latin America.7

About sixty kilometers westward along the coast, at the mouth of the González River lies at the sandbar of Chiltepec (“place of the chiles”).8 Well into the nineteenth century, vast inundations often covered lands of the center north and allowed travelers to paddle from the González directly eastward into the Grijalva without having to go overland, but modern flood control (far from perfect, it turns out) has since heightened the separation of the two. From Late Postclassical times (1200–1519) onward, most human settlement has clustered in this middle Tabascan region, along the Grijalva’s banks. The area bounded by the Grijalva to the east, Río Seco to the west, and the rerouted Mezcalapa to the south form a region known as the Chontalpa: literally, “region of foreigners,” in all probability a reference to precontact settlement by Nahuatl-speakers from central Mexico.9 Hot, low, flat, and eternally watered, it has long been Mexico’s premiere greenhouse for cacao, the tree whose seed forms the basis of chocolate.

There were rivers . . . and then there was the Usumacinta. The brave people of Tabasco feared only God and this waterway, in some mysterious way manifestations of the same being. Few men traversed its lengths, or learned its secrets. Juan Galindo (originally John Gallagher, an Irishman who came to Guatemala seeking his fortune in 1827) explored much of the territory between Tabasco and Belize, and he understood well the air of impenetrable mystery that lingered around it:

The Usumacinta is peculiarly remarkable among the rivers of this part of America, not only for the length of its course, advantages of its navigation, fertility of its banks, and superiority of the climate of its district, but also for the almost total ignorance in which even the inhabitants of the surrounding country remain with respect to its relative position, its course and branches.10

This mighty force originates in the relentless precipitation of the highland rainforests. The river’s principal tributaries are the San Pedro Martirio of the Guatemalan Petén, the Salinas-Chixoy (pronounced “Chi SHOY”) river of Guatemala’s Alta Verapaz of Guatemala’s north-central zone, and the Lacantún of southeastern Chiapas, all in turn fed by lesser tributaries such as the San Pablo, the Pasión, and the Ocosingo. Of the region’s many waterways, it was this river—the broadest, the deepest, the most volatile, the road into jungle territories little known and never to be fully understood—which dominated both commerce and the imagination. Gentleman-archaeologist John Lloyd Stephens came this way in 1840 and reported, “Amid the wildness and stillness of the majestic river, and floating in a little canoe, the effect was very extraordinary . . .”11 “I must say,” wrote the French naturalist Arthur Morelet years later, “that the scenes on the Usumacinta, by their melancholy grandeur, and primitive poetry, have left the most profound and lasting impressions on my mind.”12 The modern-day explorer will readily agree. The majestic, pale-green waterway coils through the state’s eastern lowlands like the sleepy and overfed serpent-monster of some forgotten mythology. Huge trees like the macuilí and the guayacán line its banks. Further beyond stretch fertile alluvial plains. Human beings first came here to plant corn, and their numbers paled beside the wealth of deer, alligator, turtles, and innumerable tropical birds that gathered to take advantage of the river’s bounty.13 In the late afternoon, howler monkeys awaken from their siestas and stake out their territory through a series of frightful cries that resound for miles . . . all from a timid tree-dweller slightly smaller than a chimpanzee. British explorer John Herbert Caddy took this same journey in 1840 and reported, “The noise of the large black baboon at night is awful, you would fancy a herd of wild cattle were in full combat so loud is the roaring they make.”14 Apparently it has always been thus, for the name Usumacinta is a Nahuatl derivation meaning, “place of the sacred monkeys.”15

The Grijalva and Usumacinta merge some twenty-five kilometers south of the Gulf of Mexico. The closer they come to the coast, the more they jump their low-lying banks and break into numerous smaller flows, almost as if the water were reluctant to leave Tabasco altogether. In the process, these many bifurcations create a huge marsh stretching from the Chontalpa to Lagúna de Términos, to the east. This area, known as Centla (“in the cornfield”), comprises Mexico’s most extensive wetland, and is home to fish, turtles, and innumerable species of birds.16 Spaniards steered clear of the mosquito-ridden expanse, leaving it as a region of refuge for Chontal Mayas, who understood how to make their living amid the prodigally generous marshes.

Doubtless the inhabitants of Tabasco’s many ranchos and fishing huts had their own sense of awe concerning the natural world around them, even if they never had the chance or wherewithal to write down their impressions. For these people the waters also amounted to practical matters, inescapable facts to be considered for both good and ill. The Usumacinta in particular is the quintessential big two-hearted river. For most of the year, this slow and drowsy waterway treats its inhabitants with an almost grandfatherly indulgence. Canoes skirt with ease over its surface, their occupants intent on errands of commerce and farming, or of romance, or of simple itch to be somewhere else. Its normal flow of three miles per hour makes for a gentle descent if a somewhat more taxing return.17 But in the course of their lives Tabascans became accustomed to periodic floodings that scourged the land. As if enraged by the hubris of its human offspring, the Usumacinta suddenly rises to sweep away houses and roads and bridges. These events, known as crecientes or inundaciones, concentrated in June through November, when torrential rains here and deeper inland, toward the Grijalva’s and Usumacinta’s sources, sent cascades of water racing toward the Gulf of Mexico. Normally no more than twelve to fifteen feet deep, the Usumacinta could abruptly surge by as much as twenty-five yards (one of the reasons that the ancient Mayas astutely built cities such as Yaxchilán so high atop the bluffs). The surges subsided as the waters dispersed over the vast alluvial plains from Tenosique onward. In such moments there was no hope of resisting or stopping the deluge; there was only the question of survival. But less predictable flooding at other times of the year always remained a threat, and when those floods did come, they brought death and disaster. One of the worst inundations in Tabascan memory came in 1852, hard on the heels of another terrible flood the year before. Beginning on October 17, heavy rains had begun to swell the tributaries, transforming the Usumacinta into an irresistible force. Soon the river had washed away the towns of Cerro (four hundred people) and Ríos de Usumacinta (seven hundred), and killed one-third of the some fourteen hundred inhabitants of Tenosique (“the weaver’s house”).18 Waters reached three to four meters in height, well over the tops of the smaller homes.19 When padre Tiburcio Talango lived through one such event in Teapa in 1874, he described how all human activity had to come to a stop until the fury had spent itself.20 For the inhabitants of such villages, these were disasters far more terrible than the 1847 Caste War of Yucatán, whose tremors they felt only peripherally, while the days of particularly dire catastrophes would remain in human memory decades after the event. The unanswerable power of the river is a lesson that Tabascans continue to relearn, even into the twenty-first century.

Tabasco’s byzantine network of waterways carried implications for the traveler as well as for the healer of souls. The 1892 memoir of Porfirian archaeologist Pedro Romero gives some idea of how difficult it really was to move from one town to another.21 Despite the arrival of steam engines, most of Romero’s vessels depended on wind power, particularly for coastal navigation. The relative shallowness of even the larger rivers, including the Usumacinta, permitted only vessels of relatively light tonnage. Principal river traffic consisted either of canoas, shallow flatboats capable of carrying some thirty to forty tons and perhaps equipped with primitive lateen sails; or cayucos, simply mahogany dugouts that were pulled or paddled. Travelers might go for days without encountering anything other than these two basic crafts. This capricious river remained the dominant feature of life in eastern Tabasco, just as its twin, the Grijalva, dominated the southwest.22 Karl Heller, the tireless Austrian botanist who roamed through these parts in 1848, described how boatmen on the Teapa River patiently propelled their vessel, known as a pongo, by hooking long poles to branches along the coast, then pulling themselves by walking backward along a gangplank that ran the length of the ship.23

Once beyond the coast, most of the state is a flat, low-lying plain intersected by a web of rivers. The huge Centla marshland covers much of the northeast, but from the Grijalva westward the elevation is sufficient for agriculture. This area, known as the Chontalpa, became one the most critical pockets of human settlement in the colonial and early national eras, and its landscapes are among the region’s most evocative. Cattle graze on low, broad savannas, occasionally wading deep into the marshes in search of the succulent grasses that grow in such abundance there. White egrets, or cattle-birds, follow them everywhere in search of insects. In the days before extensive habitat reduction, flocks of parrots, parakeets, and scarlet macaws, flamelike in their brilliant plumage, filled the daytime skies.24 Punctuating the scene stand stately ceiba trees, along with the shorter fan palms known as xiat (SHEE aht), prized then as now for thatching roofs. High above them, tall and slender royal palms sway in the breeze. Until quite recently, humans made no more lasting construction here than the occasional hut that was assembled from natural ...