![]()

1

Israel’s Arabs

WHO ARE THE PALESTINIAN ARABS IN ISRAEL? They are Samih al-Qasim, whose Arabic poetry has chronicled and spirited the intifadas. They are ‘Azmi Bishara, the parliamentarian, whose demands for a state of all its citizens made international headlines and earned him an exile of sorts. They are filmmaker Elie Sulieman, whose films have been canonized as Palestinian “struggle” cinema. They are Asel Asleh, the nineteen-year-old who was shot by an Israeli policeman—in the neck from behind—during the October 2000 uprising. And they are ‘Abir Kobati, the telegenic contestant on a popular Israeli reality television show, who refused to stand for the Israeli Jewish national anthem.

But they are also Sayed Kashua, whose command of Hebrew and eloquence in his second language, as if it were his “mother tongue,” have made his books popular among Israeli Jews.1 They are the manager of the Maccabi Sakhnin soccer team, who says he is proud to represent Israel in matches abroad. They are Ishmael Khaldi, a veteran of the Israeli military who tours American campuses sponsored by the Israel on Campus Coalition, singing the praises of the state. And they are Taysir al-Hayb who volunteered to serve in the Israeli military and shot and killed Tom Hurndall, a British activist in the International Solidarity Movement.

Technically speaking, Palestinians living inside the 1948 borders of Israel, unlike those living in the Occupied Territories or in the Diaspora, are citizens of the state of Israel. Numbering about 12 percent of Palestinians globally, they are largely descendants of the relatively few Palestinians who were not exiled outside the borders of the emerging state of Israel during the 1948 war. Nearing 1.25 million people, these Palestinians today find themselves a minoritized 18 percent of the Israeli population.

The answer to the question of “who are they?” of course depends on whom and when you ask. Ask Israeli Jews. Some might tell you they are the fortunate beneficiaries of Israeli rule, fully equal citizens. With the exception of some bad apples, they are supposedly happy living in the modern democratic and Jewish state and are, of course, no longer Palestinians but “Arabs of Israel.” Or some might say they are ungrateful, violent fanatics who continue to constitute a threat to the state and need to be tightly controlled. The image of Palestinians in Israel vacillates between that of docile subjects, who lead rural traditional lives in villages that make excellent destinations for exotic tourism, and that of the enemy within, the lurking demographic threat, contaminating Jewish culture and constituting a key part of the problem in the Israeli-Arab conflict.

Ask Palestinians in the West Bank city of Nablus or Rafah refugee camp in Gaza, and they might tell you that Palestinians inside Israel are largely traitors, collaborators, and people co-opted en masse whom they sometimes call Arab al-Shamenet, or “sour cream Arabs.” Shamenet is an Israeli-made creamy yogurt. The term Arab al-Shamenet mocks Palestinians in Israel as soft, addicted to this modern, Hebrew-named, Israeli-made product, and accepting of their dependency on Israel. Alternatively, they are seen as victims of a different form of the same colonial system that Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza are subjected to. “ ’48 Arabs,” as they are sometimes called, are samidun, steadfast.

Ask Palestinians in Israel about themselves, and you will also get a range of performances of diffidence, acquiescence, and contradiction. One twenty-year-old Palestinian told me: “We are doing the best we can, nobody has figured out the perfect answer. If we knew how to bring back Palestine, don’t you think we all would do it?” Palestinians inside Israel number over a million, and like many minority groups, they have learned—been forced to learn—to maneuver through a complex system, straddle multiple zones, and take on an array of contradictory challenges. They are constantly negotiating, experimenting with different strategies, being silent, being brash—or in the words of writer Kashua—they are “Dancing Arabs.”

The state tries to define them on the one hand not as a single national minority but as a fractured collection of ethnic and religious groups: Druze, Bedouin, Christian, and Muslim. On the other hand, it frequently lapses into categorizing them all in relation to the core Jewishness of the state as “non-Jews.” Indeed, the state policy of differentiation is constantly collapsing under the weight of larger Zionist imperatives, such as the appropriation of Arab land. The Druze are defined as a special and loyal minority who are conscripted into the military. Yet, like all other Arabs, they are subject to having their land expropriated for the good of the (Jewish) state. Given this schizophrenic treatment, state attempts to differentiate between subgroups seem half-baked.

The line between Palestinians inside Israel and Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza, or those in nearby Arab countries, is also a line that is constantly drawn, erased, and redrawn, blurring, fading, and reemerging. By virtue of multiple wars and generations of subjection to different state powers, and with divergent and shared histories, Palestinians inside Israel are both linked to other Palestinians and disconnected from them. Sixty years of living in the state of Israel has made them into contradictory subjects: they are formally citizens, but inferior ones, struggling, marginalized, feared by the state yet largely Hebrew-speaking, passport-carrying, and bureaucracy-engaging. On Israeli independence day, or the Palestinian day of the Nakba or Catastrophe, some of them have been pressured into experimenting with waving the Israeli flag—non-Jews awkwardly holding up the large star of David, hoping that somehow the flag will protect them, bring them closer to the fold of the Jewish state. Others suffer the consequences of waving Palestinian flags, while still others forgo flag waving altogether.

All Palestinians in Israel, however, are forced at some level—sometimes mundane, at other times more profound—to engage in absurd and contradictory practices similar to the waving of the Israeli flag. This might be as simple as the legal requirement to carry ID cards at all times—cards covered with blue plastic embossed with a menorah on the outside and a nationality entry on the inside reading Muslim, Christian, Bedouin, or Druze (to be distinguished from Jewish, and never “Palestinian” or simply Israeli).2 Palestinians inside Israel are constantly required to work within and show allegiance to a state that by definition views them as outsiders. They are forced to deal with a state that problematizes their very existence within its borders and prioritizes members of another religion, but constantly requires compliance, acquiescence, and paperwork.

A Snapshot

Consider the following snapshots. As an Arab student in Israel, you are required to study Hebrew, while your Jewish peers do not have to study Arabic. You are taught about Jewish literature and history, not Palestinian literature and history, and the security services oversee the appointment of your teachers. Upon graduating—if you make it that far—from an underfunded high school, you are not conscripted into the military as your Jewish counterparts are, unless you are Druze.3 Because of your ethnicity you are “spared” the three years of mandatory service (or two if you are a woman), as well as all the benefits that are tied to that service. When you apply to a university—none of which is Arab in Israel—your Jewish co-applicants are given preference because they have completed military service. The student loans and scholarships available to you are inferior because you have not served in the military. The faculty club on campus is a former Palestinian home from a village erased from Israeli existence and even Arabic literature is taught in Hebrew.4 You pick up an Israeli newspaper and the help-wanted ads call for veterans. You must pay extremely high taxes on privately owned land (the majority of Jews lease land from the state and do not own it privately) and all the forms are in Hebrew and everything is stamped with stars of David and menorahs. You likely live in one of the three main regions where Arabs now live—the Galilee, the Triangle, or the Naqab. Your village might be only occasionally marked on maps, or altogether unrecognized. The road signs to it, if there are any, are in Hebrew. Occasionally Arabic, usually misspelled, is added. If your village is recognized, its zoning maps were created by planners with the explicit goal of maximizing Jewish land and population. In mixed cities, where you are minoritized, Arabic street names have been changed to the Hebrew names of Zionist leaders or biblical figures. Housing prices in your neighborhood might be driven up by “gentrification-as-Judaization” and developers want to turn the old mosque down the road into a shopping mall.5 You might work in construction, where “Arab work”6 is the term used for inferior workmanship, or you might work as a doctor in a hospital where patients often express a strong preference for Jewish doctors. You might work as a cook in a Jewish restaurant opened in an old Arab home evacuated in 1948. Or you might be internally displaced yourself and employed doing renovation work on your relatives’ former home that was emptied of your relatives and is now occupied by Jews.

Even if you are lucky enough not to encounter any individual prejudice—which is widespread—there is little room for doubt that you are at best, a second-class citizen. How do Palestinians deal with this? Which of the multitude of violations of their rights and identities that they face simply by existing in this colonized space do they decide to challenge? Moments after they are born, their nationality is registered in the hospital, and the marginalization begins.7 Some of it becomes routinized and no longer given much thought since it would be nearly impossible to challenge every aspect of it. Other aspects of marginalization are of greater consequence—to income, opportunities, work options and conditions, travel, mobility, access. And yet, Palestinians in Israel have continued to play largely by the state’s rules, in the state’s game, despite—or perhaps also because of—decades of losing at that game.

The legal system in Israel has allowed and even mandated much of the injustice against Palestinians, from land expropriation to torture of political prisoners.8 Palestinian rapper Tamer Nafar chants, “I broke the law? No, no, the law broke me.”9 Yet time and again Palestinians turn to that very same legal system to seek redress. This attempt to hold state institutions to their best conceivable potential began early after the establishment of the state. For example, after brutal military sweeps of the relatively few remaining Arab cities and villages in 1949, Palestinian residents cabled petitions to the Military Administration objecting to the behavior of soldiers during the sweeps.10 Regional planning committees have the explicit goal of expanding Jewish land control and settlements in the Galilee and the Naqab. Yet Palestinians submit appeals and write letters to such committees in the hopes of keeping their land. The police shot and killed thirteen unarmed Palestinians, twelve of them citizens, during demonstrations in October 2000. Palestinians then placed their hopes on a government-appointed commission to hold the police accountable (none of the mildly reformative recommendations of this committee were carried out).11 Two hundred thousand Palestinians live in villages not formally recognized by the state because it wants to relocate them to more concentrated locations (where they will occupy less land), and thus they do not receive water, electricity, education, or health care. Members of these communities then create nongovernmental organizations that attempt to advocate—through the usual Israeli channels—for formal recognition of their villages.

In his award-winning novel The Secret Life of Saeed, Palestinian writer Emile Habiby calls his protagonist Saeed a pessoptimist—a combination of pessimist and optimist. Luckless Saeed “saves his life by succumbing to the side that has the power.”12 Not unlike Saeed, most Palestinians inside Israel play by the unfair rules of the state’s game. This is mostly because they lack other options. But it is also because somewhere in the Israeli story there is a promise, as fleeting, misleading, and unactualized as it is, of democracy. The Palestinian struggle to be included in the state—baffling as it is given repeated disappointments—seems to constitute the core of democracy in Israel (to the extent that it exists), rather than the state’s practices or institutions. Time and again, Arabs try to succeed in a game in which they desperately grasp at rules that promise them contingent rewards, even as many other rules fundamentally foreclose that possibility.

A Military With a State Attached

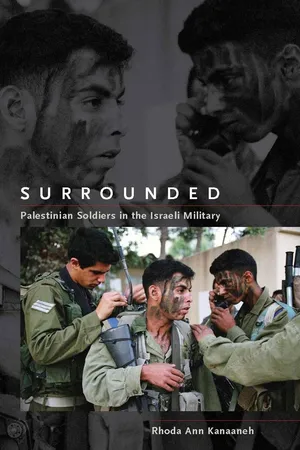

Palestinian citizens who serve in the Israeli security forces are an extreme and rare example of this trend.13 Mostly products of underfunded and badly staffed schools, with limited opportunities because they are Arab and don’t serve in the military, they decide, of all things, to serve in the military, Border Guard, or police.14 Numbering only a few thousand, they represent less than one percent of the Palestinian population.15

Military service lies at the extreme of a continuum of Palestinian strategies that range from collaboration and informing all the way to armed struggle against the state, with many different shades in between. The choice of soldiering is unpopular and rare and soldiers are considered traitors by the majority of Palestinians. But it is ...