![]()

1

Introduction

Small countries with large neighbors can face powerful military threats or irresistible market forces. China presents Taiwan with both simultaneously.1 Taiwan faces a rare dilemma in that its most important economic partner is also an existential threat, politically and economically. Its prosperity depends on its economic interdependence with China, now the world’s second-largest economy. But China explicitly intends to undermine Taiwan’s sovereignty and to achieve unification. China not only seeks beneficial economic relations with Taiwan, but also sees them as a way of promoting unification. It has drawn on its burgeoning economic resources to invest in its military capabilities, deploying advanced fighters and medium-range ballistic missiles, more than a thousand of which are aimed at Taiwan. Most importantly, China continues to threaten to use force to prevent Taiwan from declaring independence and has never renounced the use of force to promote unification.

Commercial ties with China therefore pose both challenges and opportunities for Taiwan that are qualitatively different from those presented by any other country; to Taiwan, China is both extremely attractive and uniquely dangerous. The dilemma is obvious: cross-Strait economic ties will carry many benefits, but they will also produce growing economic dependence on a country that is threatening to incorporate Taiwan, possibly by force.

Understandably, Taiwan has responded inconsistently to these contradictory pressures. Overall, it has lowered barriers to trade and investment across the Taiwan Strait; more than a million Taiwanese are now estimated to work and live in China and Taiwanese investments in China and two-way trade with China have both exceeded $130 billion. However, the evolution of Taiwan’s cross-Strait economic policies has not been smooth and continuous; it has been characterized by liberalization at some times and restriction at others. Until very recently, Taiwan banned direct shipping and air, postal, and telecommunications links with China.

Taiwan began allowing direct investment into China in 1991, taking advantage of China’s 1979 decision to set up special economic zones. But in 1994, in an early policy reversal, the Taiwan government started encouraging investment to flow toward Southeast Asia and away from China. Two years later, the government instituted formal restrictions on large-scale and strategic investments in China with the “No Haste” policy. In 2001, the newly elected Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) government replaced the No Haste with a policy of “Active Opening,” which liberalized some aspects of cross-Strait economic relations, only to reverse course again in 2006 by adopting the more restrictive policy of “Active Management.” In 2008, the Kuomintang (KMT) returned to liberalization by establishing regular and direct air links between Taiwan and China and relaxing previous restrictions on investment in China. It also conducted negotiations on an Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA), a preferential trade agreement with China ultimately signed in 2010. But as of 2014, Taiwanese direct investment projects in China still needed case-by-case approval if they involved sums of more than $50 million or restricted industries or products. Furthermore, Taiwanese companies were allowed to invest only a maximum of 60 percent of their net worth into China. A trade in services agreement, a follow-on to the ECFA, even led to the largest sustained public protest in many decades.

This pattern of controversy and oscillation calls into question the prevailing explanations for economic relations between nations. Some scholars believe external or structural factors to be particularly important in explaining small states’ foreign economic policies (Rosenau 1966). And the external pressures on Taiwan all point in the direction of liberalization, not restriction or even oscillation. Taiwan’s security guarantor, the United States, has made clear its desire for cross-Strait stability through more economic cooperation. China has likewise used generous economic incentives to encourage liberalization. In addition, the general process of globalization has also produced pressure for liberalization, especially given the natural complementarity between the two economies. Most countries in Asia and elsewhere have relied on China for low-cost labor, primarily for manufacturing; Taiwan has done so more than others, given its geographic proximity, cultural similarities and export orientation. In addition, the world is vying to export goods and services to China’s vast domestic market and growing middle class; Taiwan’s service industry is particularly well positioned to meet such demands as well. Given these structural characteristics of the contemporary global economy, it would be reasonable to expect Taiwan to be compelled to liberalize far more than to restrict.

Other scholars focus on domestic political pressures exerted by the interest groups that have emerged in a newly pluralistic society seeking to maximize their economic gain. Taiwan’s political process has become democratic since the mid-1980s, with highly competitive local and national elections virtually every year, often centering on Taiwan’s policy toward China. This approach would focus on the two main competing political parties in Taiwan: the KMT, which is seen as pro-unification, and the DPP, viewed as pro-independence. It would be plausible to predict that a DPP government would therefore adopt more restrictive economic policies toward China and that a KMT government would liberalize those restrictions. However, both the KMT and the DPP have championed liberalizing cross-Strait economic policies in some periods and restricting them in others. During the period covered in this book, there has been little correlation between the identity of the party in power and the content of cross-Strait policy. The oscillation has occurred regardless of which party has held the presidency.

The main purpose of this study is to offer a better perspective on Taiwan’s choice of economic policy toward China, especially its oscillation between liberalization and restriction, than can be provided by either of these familiar approaches. Some of the fundamental forces shaping Taiwan’s oscillating policy history actually echo similar changes in other countries. Diverging from forecasts of ever-closer economic integration among trade and investment partners, globalization has actually been accompanied by the resurgence of populism, labor movements, demands for greater economic equality, and quests for economic stability at the expense of liberalizing trade and investment policy (Garrett 1998). Local forces driven by divergent identities and interests are countering the forces of political and economic integration. In short, markets are global but politics are national—and therefore trade and investment policies are often more restrictive or more inconsistent than pure economic logic or structural pressures would predict.

The tension between economic growth and other values is more apparent all around the world; Taiwan’s dilemma is distinctive because of the combination of existential threat and economic benefit in its relations with China. In this book, I argue that national identity provides the missing key to understanding the oscillation in Taiwan’s cross-Strait economic policy. Identity is the foundation on which a community prioritizes its collective interests and formulates economic policy toward other communities. When that foundation is weak and identity is contested, prioritizing interests becomes difficult and policy may fluctuate from one extreme to another, as has happened in Taiwan. When the foundation is more consolidated and identity is uncontested, policy may still be debated among groups with differing economic outlooks and priorities, but the range of policies under consideration becomes more limited even if the intensity of the discussion remains high. This, too, has been the pattern in recent years in Taiwan.

Development of Cross-Strait Economic Relations

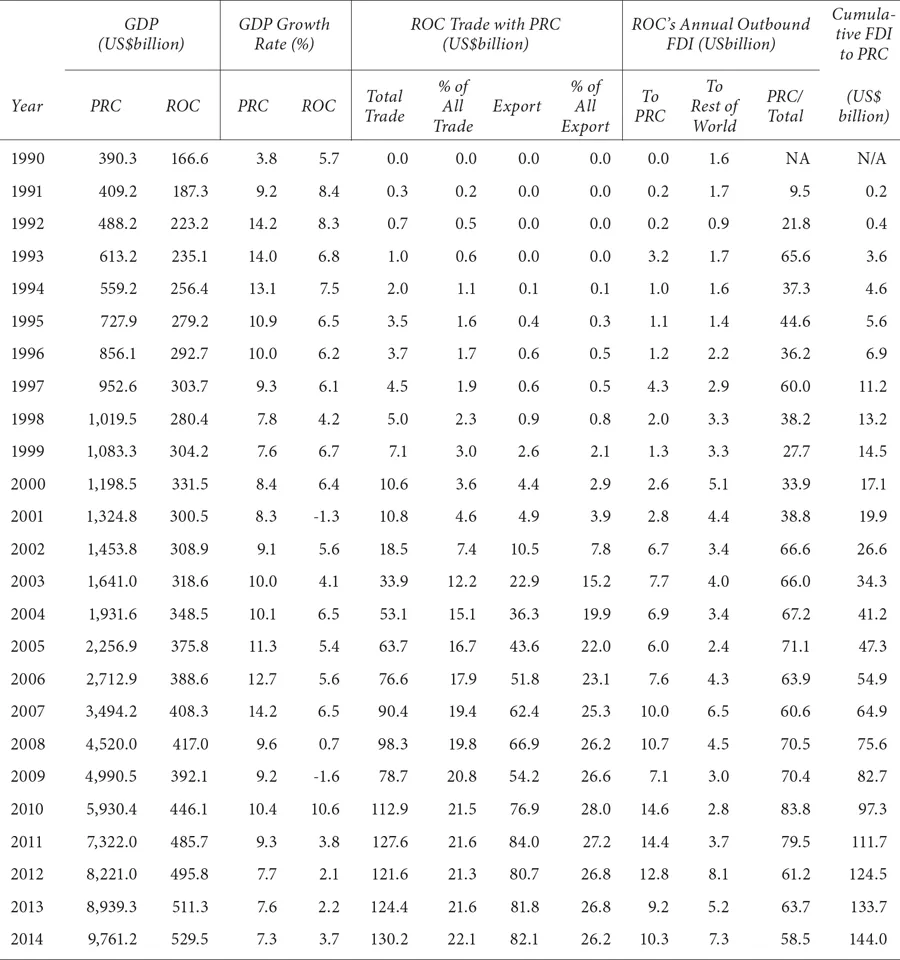

Taiwan’s economy is now structurally much more reliant on China, both as a market and as a manufacturing base, than it has ever been on any other country. Economic relations between Taiwan and China, including both trade and investment flows, have increased dramatically over the last two decades, as shown in Table 1.1.

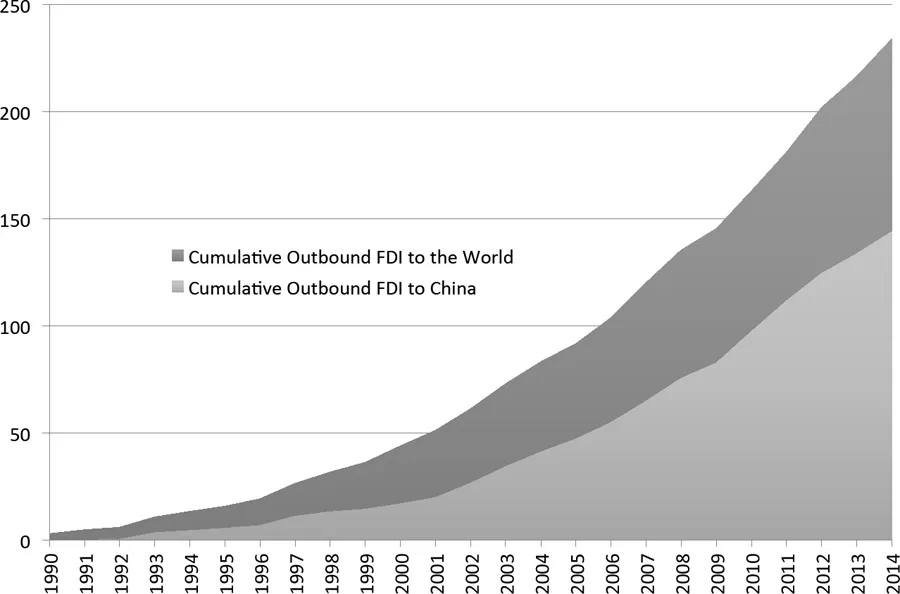

Approved Taiwanese investment in China went from a negligible amount in 1991, when it was first allowed, to a cumulative total of $144 billion as of year end 2014, exceeding the combined total of Taiwan’s outbound investments to all other countries (Fig. 1.1).2 Unofficial estimates are several multiples of the recorded approved amount. Since China began to liberalize its economy, Taiwan has always been one of its top sources of foreign direct investment (FDI), whether estimated by Beijing or Taipei. Indeed, many would claim that Taiwan is by far the leading FDI investor in China, since much of the FDI attributed to Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, and the British Virgin Islands has actually come from Taiwan. Estimates that include investments transferred through third countries are likely to be more than double the official figures. Moreover, few doubt that, if policies were more liberal, the total investment amount would be even higher.3

TABLE 1.1. Cross-Strait Economic Statistics, 1990–2014.

Sources: 1. For PRC GDP and growth rate, see International Monetary Fund, http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2013/02/weodata/weoselgr.aspx; data for 2013 and 2014 are estimates. For ROC GDP and growth rate, see Directorate of Budget, Accounting and Statistics for ROC data, http://eng.stat.gov.tw/mp.asp?mp=5; 2014 data are preliminary.

2. All trade data from Taiwan Institute of Economic Research, “Cross-Strait Economic Statistics Monthly,” no. 263, http://www.mac.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=111110&ctNode=5934&mp=3.

3. All FDI data from Investment Commission, MOEA, http://www.moeaic.gov.tw/; also available from “Cross-Strait Economic Statistics Monthly.” Includes values of previously unreported investments that were added onto totals originally reported for 1993, 1997, 1998 and all years after 2002.

FIGURE 1.1. Taiwan’s Cumulative Outbound FDI to the World and to China, 1990–2014 (US$ billion)

Source: FDI data from Investment Commission, MOEA; also available from “Cross-Strait Economic Statistics Monthly.” Includes values of previously unreported investments that were added onto totals originally reported.

As for trade, two-way flows between China and Taiwan reached $130 billion in 2014, representing 22 percent of Taiwan’s total foreign trade and up to 30 percent if trade through Hong Kong is included (Fig. 1.2). Since 1999, China has replaced the United States as Taiwan’s top export market.4 Taiwan’s exports to China have grown dramatically since 1990, from none to 26 percent ($82 billion) of Taiwan’s total exports in 2014, or nearly 40 percent if Hong Kong is included. Similarly, China has been the only country from which imports have consistently risen every year from 1996 onward. In 2006, China became Taiwan’s second-most-important source of imports after Japan, and since 2014 China has become the leading source of Taiwan’s imports, reaching $48 billion or 18 percent of the total (BOFT 2014).

The increase in cross-Strait interdependence reflected in these trends has three characteristics. First, the relationship is focused primarily on long-term capital investment, rather than trade. Up to 85 percent of Taiwan’s information and communication technology exports are manufactured outside of Taiwan—mainly in China—as part of a vertically integrated supply chain. These investments in China are therefore an integral part of many global Taiwanese companies’ strategy and cannot easily be relocated once they have been made. This is a very different pattern from commodity trade, where alternative sources can be found if one country can no longer supply a certain commodity.

A second characteristic is the qualitative change in the type of Taiwanese trade and investment. Initially, Taiwanese invested in export-oriented factories, often relocating factories previously situated on Taiwan. However, Taiwanese companies and entrepreneurs in China, known as Taishang, now want to sell their finished products in China, one of the fastest-growing domestic markets in the world. Making the products in China for the Chinese market gives the manufacturer a “just in time” advantage—as well as a cost advantage—over exports from Taiwan. In addition to components and raw materials, a large amount of the most advanced technology and machinery for these factories, especially for Taishang in the technology sector, is imported from Taiwan.

Third, Taiwan’s most competitive sectors also are moving parts of their operations to China, not just companies seeking low labor costs. The migration of low-value-added and labor-intensive assembly business, starting in the mid-1990s, initially gave Taiwanese the impression that opening up to China would mainly hollow out Taiwan’s sunset industries. Early on, however, it became clear that many of Taiwan’s most advanced companies were going to China in order to stay competitive. Electronic parts, computer components, and optical products, considered Taiwan’s leading industries and the backbone of its economy, continued to be at the top of the list of industries investing in China.5

FIGURE 1.2. Taiwan’s Trade with China, 1990–2014 (US$ billion)

Source: All trade data from Taiwan Institute of Economic Research, “Cross-Strait Economic Statistics Monthly.”

As a result, economic interdependence with China has become unavoidable if Taiwan wishes to continue to reap the benefit of a growing global economy. China’s economic opening has restructured the regional and the global economies; it has become the “factory of the world” and, importantly, one of the world’s largest consumer markets. China has become an integral part of the global supply chain and the most important economic engine for Asia and the world. Therefore, Taiwan has very few alternatives if it wishes to diversify its outbound investments and trade flows away from China in order to hedge against economic and political risks. Taiwan’s main competitors, from Korea and Japan to Thailand and Indonesia, have all become dependent on investing in and trading with China. As an economy dependent on trade, which represents more than 100 percent of its GDP, Taiwan cannot be an exception.

The changing economic balance between China and the United States has also shifted Taiwan’s economic activities away from the latter and toward the former. Whereas China and Hong Kong constituted nearly 30 percent of Taiwan’s total trade and nearly 40 percent of Taiwan’s exports in 2014, the United States, which constituted 24 percent twenty years before, now represented only 11 percent of Taiwan’s total trade and exports (BOFT 2014).

A final implication is that the economic balance of power between Taiwan and China has shifted dramatically, again in China’s favor. At the beginning, Taiwan’s investments and subsequent trade were extremely important for China. Taiwan was unique in its interest in China, especially after the 1989 Tiananmen crisis, when many multinational firms reduced their presence. Taiwanese companies expanded their global manufacturing capability by providing the capital, technology, and marketing that could leverage China’s low-cost labor. When cross-Strait trade and investment began, Taiwan was growing faster than China. This changed in 1991. Between 1990 and 2014, China’s GDP grew more than twenty-fivefold, whereas Taiwan’s grew by only three times (Fig. 1.3). In 1990, China’s economy was only a little more than twice the size of Taiwan’s, despite the huge discrepancy in population, whereas in 2014 China’s was more than eighteen times larger (Table 1.1). In terms of FDI, China has become one of the world’s leading investment destinations, reaching the top position in the world for inbound investment in 2003 and attracting nearly $124 billion of FDI in 2013 compared with Taiwan’s inflow of less than $4 billion.6 Foreign trade also shows great disparity, with China’s global trade exceeding Taiwan’s by more than seven times in 2014 (TIER 2015). Taiwan’s comparative advantage ...