![]()

PART I

GLOBAL ANALYSIS

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

WORLD POLITY TRANSFORMATIONS AND THE STATUS OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

States have sovereignty, counties have sovereignty, cities and towns have sovereignty, water districts have sovereignty, school boards have sovereignty. Why shouldn’t tribes have total sovereignty? Originally they did.

Vine Deloria Jr. (1969: 144)

SOVEREIGNTY IS A PROPERTY MOST OFTEN attributed to nation-states alone. The idea that indigenous peoples are sovereign not only challenges the core premise of international relations—namely, that sovereignty belongs exclusively to entities organized as nation-states—but also the notion that individuals, understood first as citizens and more recently as humans, are the sole bearers of rights. And yet, indigenous peoples advance morally and legally compelling claims to collective sovereignty, something that distinguishes them from most other racial and ethnic groups. Whereas most historically disadvantaged minorities seek inclusion, understood as the right of individuals to share in the economic rewards and political life of mainstream society, indigenous peoples demand— and increasingly command—the authority to sustain an institutionally and politically separate existence.

The most recent international statement on the rights of indigenous peoples, the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), is also the most comprehensive and far-reaching to date. Adopted by the U.N. General Assembly on September 13, 2007, UNDRIP marks the first time that the world community has formally and explicitly recognized the right of indigenous peoples to collective self-determination, defined as “the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs” (Article 4). Indeed, the declaration is unique among human rights accords in its emphasis on group-based as well as individual rights (Elliott and Boli 2008).

In one respect, one might say that UNDRIP was some three decades in the making, as the earliest drafts began circulating during the late 1970s. But, in another sense, many of the core rights enshrined in the declaration can ultimately be traced to the arrival of Europeans to the New World some 500 years ago. The exceptional quasi-sovereign status of indigenous peoples under international law—including, crucially, the authority to establish and control independent postsecondary institutions that such a status entails—is rooted in their treatment as autonomous nations in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century legal discourses. Yet the path from 1492 to 2007 was anything but linear. Several centuries elapsed during which indigenous peoples were denied basic human rights, much less rights as self-determining nations. Although Europeans equivocally recognized (but rarely respected) indigenous peoples’ autonomy in the decades following first contact, indigenous sovereignty underwent a centuries-long period of retrenchment before experiencing a renaissance in the post–World War II era. These historical shifts in the standing and status of indigenous peoples reflected broader changes in the world system, understood as a transnational political and cultural polity (Meyer 1980; Meyer et al. 1997a). The analysis of indigenous peoples’ rights must therefore begin with the origins and evolution of this “world polity.”

THE WORLD POLITY

The modern world polity emerged during the late medieval period with the consolidation, integration, and colonial expansion of the European polity. Its cultural origins, however, are traceable to antiquity.

Cultural Antecedents of the Modern World Polity

The deep historical and cultural foundations of the world polity lie in Hellenic philosophy, Roman jurisprudence, and Judeo-Christian theology. Despite the ecumenical thrust inherent to each mode of thought, all were characterized by a dialectical tension between universalism and particularism. Ancient Greeks acknowledged the universality of anthropos as a biological species but drew a rigid social distinction between themselves and barbaroi—anyone who couldn’t speak Greek (Pagden 1995). Aristotle, moreover, argued that barbarianism was an immutable condition that predestined whole categories of humanity to slavery. This idea persisted well into the sixteenth century, informing debates as to whether indigenous peoples should be regarded as barbarians and therefore as “natural slaves” of the Europeans.

Romans were somewhat more inclusive than their Greek predecessors. To be sure, “provincials” continued to be distinguished from different classes of citizens, but routine procedures existed for incorporating foreigners and even slaves into the civitas. Even more expansively, the jus gentium—precursor to the modern law of nations—reigned supreme over all humanity regardless of citizenship status. Roman emperors styled themselves “lords of all the world,” a title that would later be adopted by Roman Catholic popes who, as Christ’s vicars and benefactors of Constantine’s apocryphal donation, claimed universal spiritual as well as temporal jurisdiction over the world and its inhabitants (Pagden 1995). At issue here was whether indigenous peoples were subject to or outside of the European law of nations.

Christianity’s tremendous capacity for expansion is traceable at least to the Council of Jerusalem in ca. 50 C.E., when early Church leaders decreed that gentiles were allowed to convert directly to the new faith without first circumcising or observing Judaic law. Christians, of course, rarely concealed their contempt for infidels, whether Jews, Moors, or indigenous peoples; indeed, sixteenth-century Europeans debated whether the “savage” indigenes had souls. Still, absent the aggrandizing impulses of Christianity, it is doubtful whether the European polity would have become the truly world polity it is today.

World Polity Origins and Transformations

Most scholars trace the origins of the world system to the late fifteenth century, when capitalism began to display in earnest its global pretensions (Wallerstein 1974; Nederveen Pieterse 1995). But globalization had important cultural and political implications as well. The “discovery” of indigenous peoples, in addition to providing new economic opportunities for Europeans to exploit, also raised profound religious, moral, and political questions about the nature of the world and the place of Europeans in it.

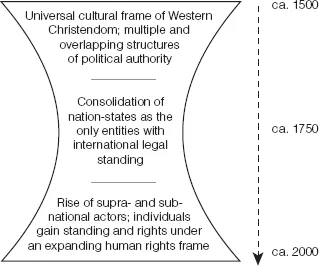

FIGURE 1.1. “Hourglass” development of the world polity, ca. 1500–ca. 2000.

The history of the world polity can be divided into three approximate periods (1500–1750, 1750–1945, 1945–present) during which different world-cultural logics—religious, statist, and “glocal” or postnational—prevailed.1 These logics, defined as “set[s] of material and symbolic constructions” that are “symbolically grounded, organizationally structured, politically defended, and technically and materially constrained” (Friedland and Alford 1991: 248–249), have shaped the basic cultural, ontological, and institutional contours of the world polity since its emergence.

To illustrate these shifts in world-cultural logics, Figure 1.1 maps the “hourglass” trajectory of the world polity from approximately 1500 to the present. The diagram portrays historical changes in the polity’s constitutive structure: the number of entities with legitimate political, legal, and normative standing. Time is arrayed vertically rather than horizontally to capture the secular—and secularizing—devolution of ultimate sovereignty first from God to states and then from states to individuals and subnational groups (Boli 1989).

Sovereignty in the nascent world polity was, as Perry Anderson (1974) put it, parcelized among an overlapping patchwork of feudal emperors, kings, princes, nobles, and lords who ruled alongside and under the auspices of the Catholic Church. The dual character of the European polity—its cultural, economic, and geographical integration but political fragmentation—made it dynamic and volatile. Diplomacy and warfare were regulated by an eclectic synthesis of Christian theology, Roman law, and humanist philosophies, resulting in a law of nations that was at once supranational and supernatural, existing “above” and prior to secular sovereigns (Williams 1990; Pagden 1995; Thornberry 2002).

The political authority of the Church and the legitimacy of its claims to universal jurisdiction waned dramatically after the Reformation in the early sixteenth century and the Peace of Westphalia in 1648.2 Territorially and culturally delimited monarchies gradually consolidated power in a centripetal process that siphoned the Church’s sovereignty from above and the nobility’s authority from below. Eventually, the religious upheaval that linked individual souls directly to God found its political corollary in the notion of citizenship, whereby the holy covenant between God and His elect was replaced by the equally sacrosanct (if still fictive) social contract between individuals and their elected sovereign.

With the decline of divinely ordained dynasties and the rise of a secularized system of states, positivism became the organizing principle of international relations. Just as social contract theorists reduced all meaningful political activity within the state to individuals, the positivist worldview recognized states as the only legitimate actors on the global stage. The desacralized law of nations no longer transcended nations (that is, supranational law) but now derived from and existed purely between them (that is, international law). At about this time, it also became common to imagine that states were homogenous communities (Anderson 1991). In most cases, of course, these imaginings remained little more than delusions until extensive nation-building projects could bring them to fruition (Weber 1976).

In the aftermath of World War II, the ontological structure of the world polity reexpanded to include newly decolonized states (Strang 1990, 1991), non-state groups (Kingsbury 1992), international organizations (Boli and Thomas 1997, 1999), transnational regimes (Krasner 1982; Donnelly 1986; Meyer, Frank, Hironaka, Schofer, and Tuma 1997b), and individuals with rights and standing independently of state membership (Soysal 1994). Meanwhile, efforts to submerge citizens under a common national identity gave way—in principle if not always in practice—to the celebration of cultural diversity, and the enjoyment of one’s native language and culture are now fundamental human rights. This postwar “disenchantment” of the nation-state coincided with a resurgence in supra- and subnational identities.3 Still, states have more to do than ever before: Education, health care, and social welfare are human rights that states are now expected to make available to citizens and non-citizens alike (Meyer et al. 1997a; Soysal 1994). And, to an unprecedented degree, a regime’s external legitimacy is contingent on the (perceived) level of internal legitimacy it enjoys. According to Paul Keal (2003: 1), “The moral standing or legitimacy of particular states is bound up with the extent to which other members of international society perceive them to be protecting the rights of their citizens.”

Colonialism in the World Polity

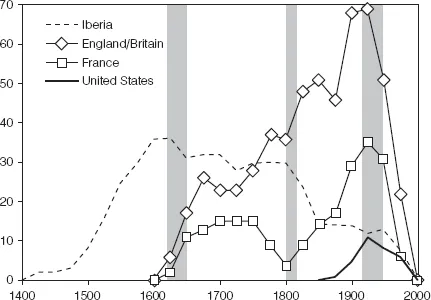

As the world polity contracted structurally during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, with national states becoming the sole receptacles of sovereignty, it expanded geographically via colonization. This expansion had tremendous and usually disastrous repercussions for indigenous peoples. Figure 1.2 charts the net number of overseas colonies held by Iberia (Portugal and Spain), the United Kingdom, France, and the United States between 1500 and 2000. Patterns of relative growth and decline were punctuated by three “global” wars identified by Immanuel Wallerstein (1983) as world-systemic watersheds—the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), the Napoleonic Wars (1800–15), and the two world wars (1914–45). These colonial eras corresponded roughly to the periods during which religious, statist, and glocal logics prevailed in the world polity.

Spain and Portugal spearheaded the first wave of Europe’s overseas excursions, under papal aegis. The Spanish and Portuguese empires peaked near the turn of the seventeenth century and receded thereafter, in lockstep with the decline of the Habsburgs and the papacy in Europe. Their last vestiges persisted until Napoleon’s invasion of Iberia presented revolutionaries in Latin America with the opportunity to wage successful independence movements. British colonial expansion during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries reinforced its own (and Protestantism’s) ascendance to hegemony in the world-system.

The sun began to set on the British Empire after reaching its zenith just prior to World War I, and rapid decolonization after World War II precipitated the incorporation of newly independent and juridically equal nation-states into the family of nations. At the same time, sovereignty was circumscribed by the ideology of human rights (Sikkink 1993; Donnelly 2003). The unabashedly statist world “polity” has become, after World War II, a more inclusive world “society” populated with a variety of nonstate actors, including indigenous peoples.

FIGURE 1.2. Net number of Iberian, British, French, and American colonies, 1400–2000.

SOURCE: Strang (1991).

Note: Shaded regions indicate periods of global warfare as identified by Wallerstein (1983): the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48), the Napoleonic Wars (1800–15), and the World Wars (1914–45).

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN THE WORLD POLITY

Changes in the normative and legal status of indigenous peoples have followed the same hourglass-shaped trajectory as the world polity in general. During the era of first contact, as feudalism waned in Europe, indigenous–colonial relations were couched in the muddled discourses of salvation and sovereignty. The redemption of savage souls justified conquest, but indigenous nations also had natural-law rights that, although frequently violated, were nevertheless clearly articulated by the leading religious and legal scholars of the day. Any pretension of indigenous peoples to sovereignty was quelled by the rise of states, after which dispossession and assimilation became policies du jour. And the contemporary erosion of national sovereignty is producing a global society vaguely reminiscent of the old feudal order, a transformation that has incubated the reemergence of indigenous peoples’ claims to sovereignty under the rubric of self-determination.

Religious Logic: Salvation and Sovereignty

Fifteenth-century Spaniards viewed their trans-Atlantic colonial excursions as the next installment of a long and venerated history of expansion that included Joshua’s conquest of Canaan (Donelan 1984; McSloy 1996), Rome’s colonization of the Iberian peninsula (Lupher 2003), the medieval Crusades (Williams 1990), and the Reconquista of Spain from the Moors. Drawing from a variety of religious and civil sources, legal scholars sometimes acknowledged the inherent sovereignty of indigenous nations and at other times vested ultimate title to their lands in Spain. Meanwhile, theologians debated the nature of the Indios, conceptualizing them alternately as rational humans or savage barbarians, little better than peasants (Vitoria [1557] 1917: 127–128).

Shortly after Columbus’s fortuitous landfall in the New World, Spain dispatched envoys to Rome for papal validation of his “discovery.” Authorization was given in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI, himself a Spaniard, in the bull Inter caetera. Alexander’s bull granted sovereignty over most of the Americas to Spain on the condition that the Spaniards convert the native inhabitants to Christianity. Over the next two centuries, Spain grounded its territorial claims to the New World exclusively in the papal bull.

Despite having received the imprimatur of Christ’s worldly representative, the Spanish Crown remained curiously obsessed with justifying its presence in the New World (Hanke 1959). In 1512, King Ferdinand sought the advice of Dominican theologian Matías de Paz and civil jurist Juan Lopez de Palacios Rubios, who concluded that “the Indians had complete rights of personal liberty and ownership but that the king was entitled to rule over them because the Pope had universal temporal and spiritual lordship and had granted him this right” (Donelan 1984: 83). Dominium, or ownership rights, resided in the Indians, but imperium—ultimate sovereignty—was vested in the Spanish monarch by virtue of the papal donation.

With its legal claims to America so validated, Spain and the papacy turned their attention to the normative and legal status of the continent’s native inhabitants. The Laws of Burgos, enacted in 1513, provided for the Indians’ conversion to Christianity, and the New Laws of 1542 manumitted all but a small number of Indian slaves by making them direct subjects of the Spanish Crown. In the interim, Pope Paul III had declared in Sublimis Deus (1537) that “the Indians are truly men and… are by no means to be deprived of their liberty or the possession of their property, even though they be outside the faith of Jesus Christ” (Washburn 1995: 13). However, t...