![]()

PART I

MODERNIZATION

![]()

1

A Relic of the Past, Fast Disappearing

Until the end of the Second World War, Prishtina was a typical Oriental town, with small one-story houses and narrow streets. Only after the Liberation has Prishtina passed through strong economic, cultural, and social development—and grown into a completely new modern town.

ESAD MEKULI AND DRAGAN ČUKIĆ, EDS., Prishtina

Anything about which one knows that one soon will not have it around becomes an image.

WALTER BENJAMIN, “The Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire”

War by Other Means

In the mid-1960s, the Yugoslav government published a number of books on the progress of socialist modernization in their country. Many books were published in 1965, the twentieth anniversary of the end of the Second World War. This was a war in which the Communist Party of Yugoslavia’s Partisan forces, under the leadership of Josip Brož Tito, defeated Yugoslavia’s German and Italian occupiers, along with their domestic allies. Soon after establishing Yugoslavia as a socialist state, with Tito as its president-for-life, the Communist Party set out on an ambitious program of modernization. Publishing the results of that program on and around the twentieth anniversary of the war’s ending placed modernization in the history of war: in Yugoslav socialism, modernization was staged as a war of its own.

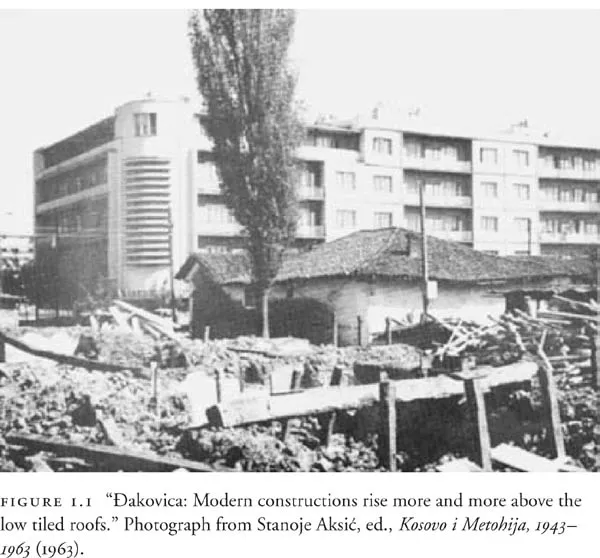

One such account of socialist modernization was Kosovo i Metohija, 1943–1963 (Kosovo and Metohija, 1943–1963).1 In socialist Yugoslavia, Kosovo was a province of Serbia, one of Yugoslavia’s six constituent republics, just as it had been in prewar Yugoslavia and in Serbia before Yugoslavia’s founding. Kosovo i Metohija, 1943–1963 was published by Kosovo’s provincial government for its constituents. The book’s many photographs frequently visualized modernization with images of architecture. One photograph, from the city of Gjakova/Đakovica, showed, in the foreground, a half-destroyed group of mud-brick houses and, in the background, a tall, white apartment block (Figure 1.1). Architectural oppositions between the houses and the apartment block behind them are manifold—I have already emplotted some of them in my description of the photograph—and the caption of the photograph foregrounded several. These oppositions—modern versus historic, high versus low, concrete versus tiled—suggest, in turn, still another opposition, that between the intelligible (here, modernization) and the sensible (here, architecture). In this sense, the photograph represents the manifestation of modernization in, among other things, architecture.

The force of this representation was its status as documentation: a representation of a reality prior to and outside the scene of the photograph. Architecture, as well as the photograph that represented it, would be an apparent effect or product of modernization and therefore evidence of the latter’s very existence. But the impossibility of modernization, whether as concept, ideology, or object, to manifest itself simply as such suggests that representation did not only reproduce an aspect of modernization but also produced its aspect—its otherwise absent or obscure appearance. Here, architecture, as well as its subsequent photographic representation, comprised a performance of modernization, a visualization of modernization that was inscribed in modernization’s very concept. As such, photography and architecture are less ex post facto depictions of modernization than practices within modernization, reconciliations of concepts of modernization with material actuality that reciprocally form and transform both in that process.

In socialist Yugoslavia, the performance of modernization engaged architecture in two guises. In one guise, architecture was an object of construction, the “modern constructions” that manifested what modernization was; in another guise, architecture was an object of destruction, an abject heritage of premodernity that made manifest what modernization was not. Construction and destruction thereby comprised conjoined architectural supplements of modernization. Each supplement added onto modernization, comprising a mediation or effect of it, but at the same time, “this addition is a floating one because it comes to perform a vicarious function, to supplement a lack on the part of the signified.”2 This lack was the very incompleteness of modernization as a concept, the incompleteness that required this concept to be supplemented by architecture in the first place. The dichotomizing opposition of modern and historical architecture, staged in the photograph from Gjakova, thus led to the mutually constituting relation of modernization and architecture.

According to humanist theories of modernization, however, modernization—whether as historical process, economic mode of production, or cultural ideology—is taken to be separate from its “manifestations,” architectural or otherwise. As simple mediations or effects, modernization’s architectural manifestations can thereby be reduced to modernization-assuch. Humanist theorizations of modernization rely, in particular, upon an underlying historicism: history comprises time unfolding as progress, itself figured by such terms as peace, prosperity, freedom, equality, or democracy. Architecture thereby emerges as a manifestation of one or some of these figures. In capitalist contexts, modernist progress takes the form of “development,” which is furthered by the “creative destruction” that opens up new opportunities for capital accumulation and sustains economic growth. In socialist contexts, like that of the former Yugoslavia, modernist progress took the form of “revolution” and destruction’s creativity lay in its status as a motor of revolutionary change. In the Communist Manifesto Marx and Engels famously proclaimed that, in modernity, “all that is solid melts into air”—but the destruction that this transience implied was redemptive, a necessary phase in the social evolution that would lead to communism. In either case, however, construction and destruction are reduced to a mere acting-out of a progressive modernization that stands conceptually apart from its architectural mediation.

In this context, Walter Benjamin’s account of Baron Haussmann’s mid-nineteenth-century modernization of Paris is distinct in its refusal to recuperate modernist destruction. Haussmann’s architectural modernization of Paris—one of the first great urban modernization projects—was posed by the French state as a necessary transformation of the city and of society itself. Benjamin quoted Maxime Du Camp on the perceived “uninhabitability” of pre-Haussmann Paris, in which “the people choked in the narrow, dirty, convoluted old streets, where they remained packed in.”3 Haussmann’s broad boulevards were to bring light and air into previously dark and claustrophobic working-class neighborhoods, the slums of those neighborhoods were to be cleared, and the working class was to be provided with the civic amenities previously accessible only to the bourgeoisie.

Yet, for Benjamin, this all comprised “strategic beautification.” While Haussmann relied upon the perceived reducibility of architectural transformation to social transformation, his modernization of Paris actually served, for Benjamin, as a substitute for and preemption of social change. Class antagonisms and social suffering were, for Benjamin, concealed rather than eliminated in Haussmanization, with the Parisian working class dispatched to the city’s periphery and their former neighborhoods, though shot through with grand avenues, depleted of “their characteristic physiognomy.”4 Haussmann’s modernization thereby secured Paris against the workers’ uprisings that, for Benjamin, provided the sole chance for actual social change: its destruction did not reduce to modernization-as-progress but to a preventive war against organized labor.5 Haussmannization, then, was war by other means, so that, for Benjamin, it was profoundly related to other forms of political violence. The end of the failed 1871 Paris commune in the “burning of Paris” was “a fitting conclusion to Haussmann’s work of destruction.”6 And, as Susan Buck-Morss has observed, Benjamin also described the urban battlefields of cities in the Spanish Civil War by reference to the destructive technology developed in Haussmann’s Paris. “Haussmann’s activity,” Benjamin wrote in 1935, “is today accomplished by very different means, as the Spanish Civil War demonstrates.”7

The destruction that Haussmannization at once instrumentalized and obscured was, for Benjamin, the key to its violence. Yet Kosovo’s modernization does not simply offer itself for reinscription in Benjamin’s text as another instance of modernizing violence; it enables, rather, a historical relation to be drawn between itself and that text. Benjamin posed the conjunction of modernization and war as a critical insight, a revelation of a crucial aspect of modernization, but one concealed by its architectural constructions. To figure Haussmannization as war was thus to disclose its violence. But the figuration of modernization as war was explicit and operational within Kosovo’s modernization. Just as Benjamin described Haussmann’s boulevards “covered over with tarpaulins and revealed like monuments,” so was the destruction of Kosovo’s abject heritage the subject of visual and textual representations that revealed this destruction, too, as a monument of modernist progress.8 Kosovo’s modernization attempted to recuperate precisely the destruction that, according to Benjamin, was disavowed in Haussmannization. While Haussmann’s constructions comprised ideological justifications for and physical concealments of the destruction that preceded and motivated them, the destruction in Kosovo’s cities was specifically enfolded in a modernist narrative of war by other means: war was figured as both representation and instrument of historical progress. In Kosovo, this war was carried out against a debased heritage whose destruction manifested modernization. Supplemented, in the strict sense, by destruction, modernization made of Kosovo’s history an architectural phenomenon and its politics an architectural praxis.

We Destroyed on Sundays

Yugoslavia’s modernization after the Second World War was a form of reconstruction, a reaction to the war’s thorough devastation; it was a form of socialism, a response to capitalist underdevelopment; a form of industrialization, an attempt to insert Yugoslavia into wider European and global economies; and a form of historical progress, a means of propelling Yugoslavia forward on the teleological trajectory that would led to communism. Each of these formulations invoked a prehistory, the premodern, against which modernization appeared. Though this premodernity was temporally “before” modernization, it emerged as a concept with, in, and by modernization. Modernization, therefore, involved the production of the premodernity that would be “discarded,” “replaced,” “abandoned,” “overcome,” or “destroyed”—to cite but a few names the process was given in socialist Yugoslavia—by modernization. Premodernity was just as much a product of modernization as the industrialization of production, the reconciliation of city and countryside, secularism, public education, social welfare, and other such goods that modernization claimed for itself. Modernization also was, that is, a form of historicism, stipulating both what was inside and outside of it according to a continuous and linear temporal trajectory.

Many empirical histories of socialist modernization stage their object against an inherited and objective premodernity, which is then emplotted as an obstacle to modernization.9 With some of Yugoslavia’s republics and provinces emerging from an “advanced” Austro-Hungarian empire (Croatia, Slovenia, Vojvodina), some from a “backward” Ottoman empire (Bosnia, Kosovo, Macedonia), and some from both empires (Serbia), many histories pose premodernity as the source of the “inequalities” in Yugoslavia that modernization had to overcome. Other histories pose premodernity as a “resistance” to modernization where premodernity existed “in surplus,” as in places formerly under Ottoman rule. Still other histories pose premodernity as a cover term for other phenomena, such as Orientalism, Eurocentrism, or racism, which were themselves objectively present and causal on modernization. These histories therefore repeat, in the guise of analysis, a concept produced within modernization itself. They are histories of modernization that are themselves modernist. They fold premodernity’s “origins,” “signs,” “symptoms,” “products,” and “failures” into the concept of premodernity, a second-order reification of a concept that was already reified in and by modernization.

One of the primary examples of the reification of premodernity in socialist Yugoslavia was architectural. This reification possessed a double aspect. One aspect was defined by “cultural monuments,” or heritage that was named as such, valorized, studied, and protected. This process produced premodernity as an inheritance to be “preserved,” with the very concept of preservation reproducing the ideology of p...