![]()

1

THE TOUCHSTONE

A man there came, whence none could tell,

Bearing a touchstone in his hand,

And tested all things in the land,

By its unerring spell.

William Allingham, “The Touchstone”1

JOHN BROWN TESTED AMERICA. As the Irish poet William Allingham saw, Brown was like a touchstone: a quartz-hard surface against which the metal of the nation could be rubbed to reveal its true composition. Like a touchstone, Brown could assay the qualities of others while remaining opaque himself. Brown both baffled and fascinated the people who met him. He spoke as plainly as a person could speak, but just this plainness made him an enigma even to his allies. Brown’s impenetrability elicited argument, conviction, even theology. Thus the touchstone did its work. Rubbed against the hard opacity of John Brown, individuals and institutions showed themselves for what they were.2

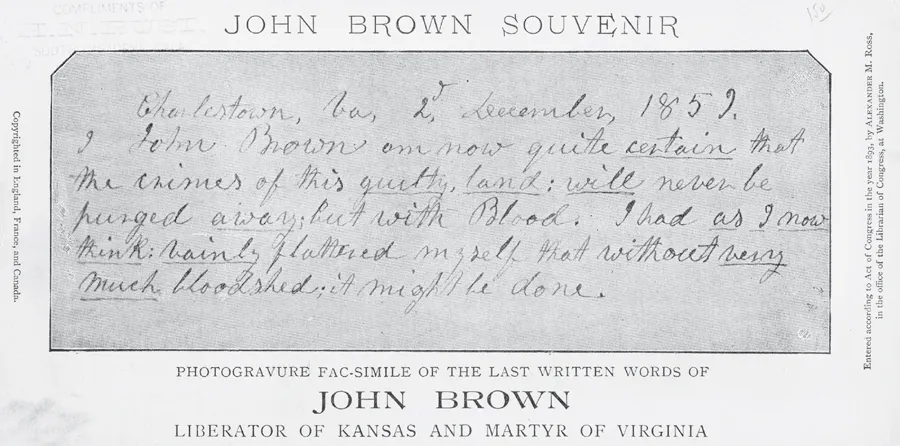

Brown’s powers to assay have been renewed in every age since his death. Again and again thinkers have pressed the questions of the day against the hard memory of John Brown. Brown’s execution sparked a spiral of reactions and reactions to reactions that polarized North and South and helped push the nation into war. After the war Frederick Douglass hailed Reconstruction as a project that would finish the work Brown started. When Reconstruction was undermined by desires for reconciliation between Northern and Southern whites, entrepreneurs repackaged Brown as a sensational event that could be shared in a renewed national memory. They transported the blockhouse in which he made his last stand to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago and sold souvenirs engraved with his last words, which described the blood that would be required for redemption of the nation (see Figure 1.1).3

FIGURE 1.1 “John Brown Souvenir” from the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, 1893. Boyd B. Stutler Collection, West Virginia State Archives.

Not everyone at the turn of the century accepted this transformation of Brown into a fairground attraction. Insisting on the unfinished quality of any redemption, W. E. B. Du Bois led a group in the first decade of the twentieth century in founding the Niagara Movement at the site of Brown’s raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry. In that same decade socialist leader Eugene V. Debs decried the oppression of workers and called for a “John Brown of wage slavery.” A few years later Social Gospel preacher Charles Sheldon celebrated Brown’s muscular Christianity in contrast to “those soft youth this nation rears.” In the 1930s Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes reclaimed Brown for a new generation’s judgment of the segregation that still prevailed. In these same decades most white American views were turning sharply against Brown. Those currents found vivid expression in The Santa Fe Trail, a 1940 film that projected a crazed, homicidal Brown on movie screens across the country. A similar image, muted by the genre of the academic essay, stood behind C. Vann Woodward’s use of Brown to condemn Cold War fanatics on every side.4

As the movement for civil rights gained strength in the second half of the twentieth century, more positive images of Brown returned to national prominence. Both Lerone Bennett Jr. and Malcolm X recalled Brown’s example in criticism of more tepid white liberals. More sympathetic novels and biographies by white authors also began to appear again. But attention to civil rights waned at the turn of millennium and then, after September 11, 2001, was largely overwhelmed by national preoccupations with terrorism. Readings of Brown registered the shift. They came to be dominated by questions about religion, extremism, and violence. In the years since 9/11 Christopher Hitchens, Barbara Ehrenreich, and a host of others have invoked Brown in the course of arguments about terrorism. Museums have told Brown’s story in order to ask if Brown was “so different from today’s bombers from Oklahoma City to Iraq.” Timothy McVeigh, who blew up the Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, had his own answer to that question. He explicitly appealed to Brown as a precedent. In the most recent years, as concerns have arisen not only about terrorism but also about the state’s response to fear of terrorism, Brown has been invoked again. Cornel West recently tweeted that “Brother Edward Snowden is the John Brown of the National Security State.” As these examples show, the touchstone of John Brown is not only revelatory but also mutable—and combustible. This touchstone is not kept safely under glass in a museum.5

Brown has been such a significant touchstone for American political imaginations in part because of his ability to figure sovereignty.6 In speaking of “sovereignty,” I mean to describe a kind of authority that goes beyond the law, a righteous power that can ground, legitimate, limit, exceed, and even overturn the law. Because Brown claimed that kind of authority for his work, Brown’s story has the power to make the questions of sovereignty concrete. The story of John Brown asks whether such a notion of sovereignty should play any role at all in our political reasoning. It presses the question of whether there is a “higher law” that can legitimate actions that defy the laws of the state. It asks where such sovereign authority might reside, how it might be known, and how it might relate to individuals, states, and movements in this age. It asks about the possibility of a sovereign pardon that would run beyond and even against anything ethics might require. It asks whether it makes sense to speak of any sovereign power at work in history and what role sovereign violence might play in the unfolding of history. John Brown’s story asks if the state should have a monopoly on the means of legitimate violence. It asks what, if anything, God might make of violence. John Brown’s story makes visible some of the most basic questions of political theology. Indeed, talk about Brown has served as one of the most important genres in which Americans have done political theology over the last 150 years.

To make sovereignty visible for America is no small feat, for Americans cast off the most established ways of figuring sovereignty when they cast off monarchy. As Ernst Kantorowicz argued, European nations came to understand the sovereign as having two bodies, one “natural” and the other “politic.” The king’s natural body might be subject to disability, moral failing, and even mortality, but the body politic represented, “like the angels, the Immutable within Time.” Sharing in God’s own rule, the body politic secured the legitimacy of the rule exerted by the king’s natural body. The king’s natural body was “backed” and “underwritten,” in Eric Santner’s words, by the sacred flesh of the body politic. And the body politic was in turn realized in the king’s natural body. The king’s complex body was sovereign power made flesh.7

America’s rejection of a king disrupted these conventions by which sovereignty could appear. In one strand of republican political theory, the people moved into the role of the sovereign. If the locus of the sovereign’s natural body changed, the logic of sovereignty did not.8 But “the people” has always been a plural and dispersed reality. It is difficult for something like the natural body of a sovereign people to appear, and even more difficult for it to act in decisive ways. Moreover, the transfer of sovereignty to the people created a need for some new narrative that could give ultimate legitimation to the political body of the sovereign people and then tie that political body to a natural counterpart.

Stories of American exceptionalism have helped fill this need. They have linked the American people to the redeeming work of God in the world and so underwritten the sovereignty of the people. But even these stories need focal points. They depend on individuals and events that represent the people as a whole. John Brown has often been pressed into this role. Variously cast as Puritan, frontiersman, heir to the Revolution, Yankee, transcendentalist, and more, Brown has served as a figure of the American people. As Henry David Thoreau said in an 1859 address, “No man in America has ever stood up so persistently and effectively for the dignity of human nature, knowing himself for a man, and the equal of any and all governments. In that sense he was the most American of us all.”9 Even those who have loathed Brown have tended to assign him some representative role. The “most American of us all” has been a site for making the people visible to itself, for arguing about the virtues and vices of the people, and for asking whether the body politic of the people is connected to God in ways that underwrite its authority in relation to law. When the people are taken to be sovereign, and John Brown is taken to stand for the people exactly at their point of connection—or lack of connection—to an authority beyond themselves, arguments about the character of John Brown can become arguments about sovereignty.

Arguments that have used Brown to figure sovereignty have often wrenched him out of the wide network of relationships in which he actually lived and acted. The Brown of political memory typically stands apart from important relationships with family members, business partners, fellow raiders, wealthy backers who supplied money and weapons, and many others, both black and white. At times in this book I engage Brown’s story on those terms, for they are the terms that order political memories, and one of my hopes is to intervene in those memories. The body politic matters. At other times—as when considering pardon or the temptation to narratives of blood sacrifice—I try to stress the political significance of remembering Brown in the dense network of relationships in which he actually lived. Whether Brown’s relationships are in the foreground or the background of my depictions of him, they are always there. The natural body must not be ignored.

John Brown’s body has helped figure sovereignty for a polity in which sovereignty is often invisible. Part of this invisibility comes from the ideal of a sovereign people. But another strand of republican political theory has made sovereignty even more difficult to discuss directly. This strand would reject any reference to authority outside or beyond the law. Hannah Arendt articulated this view when she argued, “The great, and in the long run, perhaps the greatest American innovation in politics as such was the consistent abolition of sovereignty within the body politic of the republic, the insight that in the realm of human affairs sovereignty and tyranny are the same.”10 Such an ideal would bury questions of sovereignty, not so much answering them as smothering them. When the rule of law is taken to exclude reference to any power beyond the law, discussions of sovereignty have to happen with borrowed resources and in fugitive forms.

These fugitive deliberations have happened in different sites in different eras. Talal Asad has argued that the figure of the suicide bomber has served as one such site in the years since September 11, 2001. In Asad’s view, the suicide bomber is a figure through which liberal democracies work out the repressed knowledge of the lawless violence at work in their own founding and ongoing existence—the sovereignty that dare not speak its name. As a figure for the return of the repressed, the suicide bomber both fascinates and repels. As a figure freighted with significance for its interpreters, the suicide bomber elicits not just ordinary police action but endless discourses of interpretation. These attempts to explain suicide bombing, Asad wrote, “tell us more about liberal assumptions of religious subjectivities and political violence than they do about what is ostensibly being explained.”11 Because these explanatory discourses reveal assumptions of political theology that often remain unarticulated, they can become a site for critical conversation.

John Brown has played a role like the one Asad describes for suicide bombers for almost two centuries.12 Brown holds a special place in American political imaginations because of the wide sympathy for the ends he sought. For most Americans, the 9/11 hijackers can be condemned on the basis of their cause alone. And if their end was not good, their use of violent means beyond the law never becomes a serious question. Questions of sovereignty can be evaded. But Brown cannot be dismissed so easily. As Du Bois wrote, Brown poses the “riddle of the Sphinx” because he was right about so much.13 Brown was right that slavery was an abomination. And he was right that legal means were not going to break the system of slavery anytime soon. Enslaved people had been emancipated in fits and starts in Northern states in the years after the Revolution, but by the 1850s the formal political processes that might have produced complete emancipation had ground to a standstill. Moral suasion might have moved some hearts, but it was no serious threat to entrenched slavery in the South. In the end it was bloodshed, and bloodshed that the law had to scramble to accommodate, that ended slavery in the United States. If it could have happened another way, it did not. Widespread acceptance of Brown’s ends puts the question of his means in terms that are difficult to evade. Because those means included violence beyond the law, Brown raises questions of sovereignty in direct and vivid forms.

Like a European monarch, John Brown has two bodies. What Kantorowicz would have called Brown’s natural body lies a mouldering in the grave, just as the song says, but Brown’s soul, his body politic, marches on as a figure for sovereignty in a nation with deep suspicions of sovereignty. Kantorowicz described the medieval king’s body politic as providing a kind of stability and security for the realm. The ability of later rulers to share in this body guaranteed a continuity of legitimate power. The living body of John Brown offers no such assurances. It is not immutable but different in every age. It appears again and again, but not as a steady statement that can undergird ongoing claims to sovereignty. The living body of John Brown appears instead as an interruption, a question posed to successive moments in national history. It does not so much secure existing powers as reveal them for what they are. The hard rock of John Brown is not a foundation but a touchstone.

The Natural Body of John Brown

This book focuses especially on the body politic of John Brown. But the best reflections on Brown’s political body will not float free from empirical histories of his natural body. They will instead cling closely to this body, seeking new angles of vision from a spot close to the ground.

Born in Torrington, Connecticut, in 1800, Brown grew up in a family with deep roots in Puritan New England and a strong commitment to the abolition of slavery.14 The family moved to the Western Reserve in 1805, part of a wave of migration from New England. Brown would suffer a lifetime of losses, and they started early. His mother,...