![]()

CHAPTER ONE

War

What Was Lost

According to conventionally cited statistics, the Taiping Rebellion, which lasted from 1850 to 1864, cost twenty to thirty million people their lives.1 On that basis, it has been termed the most devastating civil war in human history. A precise body count (or even an approximate one) is, in retrospect, impossible, as has been demonstrated recently by several inconclusive articles on population loss in this period.2 Contemporary accounts suggest extraordinary carnage and destruction. Memoirs and local gazetteers compiled in the postwar period refer with appalling frequency to population loss approaching or surpassing 50 percent in cities and towns throughout the lower Yangzi region and describe unspeakable human suffering.3 But whether or not these numbers are accurate, the death toll surely was much larger than that in the exactly contemporaneous American Civil War, a conflict in which some 620,000 soldiers and perhaps 50,000 civilians died.4

And yet, in spite of its devastating scope, the Taiping Rebellion remains relatively unknown outside of China, compared to events that were arguably of less far-reaching and transformative significance.5 Even within the China field, accounts of the Taiping Rebellion have been remarkably bloodless; we have been preoccupied with abstract ideological questions rather than with damage. Scholars seeking to explain the late-nineteenth-century rise of Shanghai routinely allude to the arrival of migrants from the prosperous and cultured Jiangnan region, without reference to the ruination that impelled them to move. In teaching about the Taiping Rebellion, historians of China typically gesture toward the fact of its having been the most devastating civil war in history or cite the appalling statistic of twenty to thirty million. But then we (myself included) lecture about Jesus Christ’s Younger Brother and his odd vision to the delighted amazement of our students. It is time to reconsider these priorities.

A decade ago, as I finished writing Building Culture in Early Qing Yangzhou, a book about the construction of scenic sites in Yangzhou in the aftermath of the Manchu Conquest of that city in 1645, I realized that I had yet to examine the 1874 gazetteer for Yangzhou prefecture—held in the collection of the Library of Congress, only a few blocks from where I live.6 I walked over to spend what I thought would be an hour or two ensuring that I had at least looked at all of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) gazetteers for Yangzhou prefecture. But what I found that day in that book changed the way I understood my project, by rewriting the ending. It also opened the way to an entirely new set of questions and pointed toward this present study. I was shocked to learn that nearly all of the sites discussed in Building Culture (and much else) had been destroyed during the Taiping War of the mid-nineteenth century.7 I was, moreover, stunned to find that the 1874 gazetteer for Yangzhou prefecture documented in carefully stylized form the honorable deaths of a very large number of local residents who killed themselves or who were killed when the Taiping armies occupied Yangzhou. I had been studying Qing history for more than a decade. I had read books about the Taiping rebellion. I had given lectures on it in my classes. And I had never really thought about what it might have meant at the local level to the millions of people who had lost their lives, livelihood, and loved ones.

I spent the next several days reading the literally hundreds of accounts of the deaths of the loyal and righteous, even though these stories had no direct bearing on the project that I was trying to finish. A gazetteer is a topically organized compendium of materials on local topics edited by local elites under the formal oversight of officials and in accordance with fairly well-established principles of inclusion. Although earlier editions of Qing gazetteers typically included biographies of moral exemplars including chaste women, loyal and righteous or filial men, and outstanding officials or literary figures, this edition spotlighted the loyal and righteous dead. As I later learned, emphasis on the loyal and righteous was typical of post-Taiping gazetteers produced in this region, as was the format in which they were presented. The stories of the exemplary dead were highly patterned, offering little more than name, social status, place, and means of death. For instance, in the Yangzhou gazetteer from 1874 we find, among many others: “Military Student, Zhu Wanchun. When the city fell and there was fighting in the lanes, the rebels used guns to surround him. He died in the gunfire.”8 “Zhao Jialin was taken as a prisoner to the pagoda at Sanchahe in 1856. The rebels stored gunpowder there and he lit a match that he had brought with him. This blew up the pagoda and killed several thousand rebels. Zhao also lost his life.”9

The gazetteer describes martyrs sliced, stabbed, hacked, burned, or cut down for talking back; martyrs who died by drowning, hanging, self-immolation, self-starvation, or poison. Centered upon the moment of death, each story captures the essential act of resistance against the rebels. Each of the people so recorded was thereby translated from a living person into a moral exemplar embodying loyalty to the dynasty. In the process of translation, each was reduced to a single political and moral meaning. Nothing remains of their personalities or experiences beyond what could be construed as righteous or loyal. But all are named, situated, and caught in the act whereby their lives were extinguished—the moment that proved them worthy of commemoration. I wondered what had become of all the dead bodies; how had funerals been conducted in wartime? How seriously had survivors taken state-sponsored honors in the immediate aftermath of the war? What were the emotional implications of loss for those who lived? And what evidence of an emotional response might be found in a commemorative landscape seemingly and predictably dominated by state honors?

Official remembrance rendered the dead meaningful within a very particular political context and discourse. Through the use of morally charged language, ordinary men and women were recast as martyrs and the violence of their deaths was imbued with political meaning and moral weight. Local elites produced morality tales of honorable death and submitted them for recognition up a hierarchy of provincial and metropolitan officials. They built shrines celebrating the war dead, framing them in accordance with values and institutions developed during the Qing dynasty. And yet, within decades, the stories of those who had died ostensibly for the dynasty had been deliberately forgotten, overwritten by new national imperatives. By the end of the nineteenth century, the more distant violence of the Qing conquest of the Jiangnan region in 1645 had become the consummate icon of local suffering, replacing more recent events in popular memory. Interpretations shifted. In the gazetteers of the 1870s and 1880s, communal loyalty unto death for the Ming dynasty in the seventeenth century was understood to foreshadow loyalty unto death for the Qing in the early 1860s. The value celebrated by terrible analogy was loyalty above all else. By the turn of the twentieth century, the story of the Qing conquest had acquired new meanings: rather than encoding loyalty, it stood for national humiliation. More recent martyrdom in the name of the discredited dynasty lost all resonance; the mid-nineteenth-century struggle acquired a new set of heroes and meanings.

The public focus on the righteousness and heroism of the martyred dead facilitated erasure of wartime mayhem and brutality from historical memory; systematic elimination of Taiping texts ensured (in the short run) the relative absence of alternative accounts. After the 1911 Revolution, new revolutionary martyrs quite literally displaced those honored by the dynasty. Shrines honoring the dead from the Taiping War were repurposed and renamed to honor those who died founding the Republic. Texts and stories that did not re-inscribe the new conventional wisdom of Taiping heroism and its Qing antithesis were subject to either misinterpretation or neglect. Sources affirming Taiping heroism were recovered from collections abroad or invented wholesale. Neither revolutionary nor progressive, those who ostensibly died for the dynasty in the mid-nineteenth century became, in the twentieth century, extraneous to the dominant narratives of modern Chinese history, which reversed the verdicts on the war, the dynasty, the rebels, and the dead. New visions of the greater national good obscured meaningless violence, emotion, and loss. The terms in which their deaths had been commemorated were no longer meaningful. And, contrary to the gazetteer editors’ purpose, memory of the war dead was extinguished.

Rebellion, Revolution, War

The story of China’s nineteenth-century civil war has most often been narrated as the biography of a visionary or of the proto-revolutionary movement he inspired. In 1837, Hong Xiuquan, a failed examination candidate from Guangdong Province in China’s Deep South, fell into a trance and was troubled by visions, which he later (in 1843) interpreted through a Christian tract that he had received from a Chinese evangelist several years earlier. He proclaimed himself the second son of the Heavenly Father, and thus, the younger brother of Jesus Christ. He gathered followers in his hometown, and, after 1844, in the mountains of Guangxi, developed a system of religious and quotidian practices that formed the basis of his radical challenge to the prevailing dynastic order.10

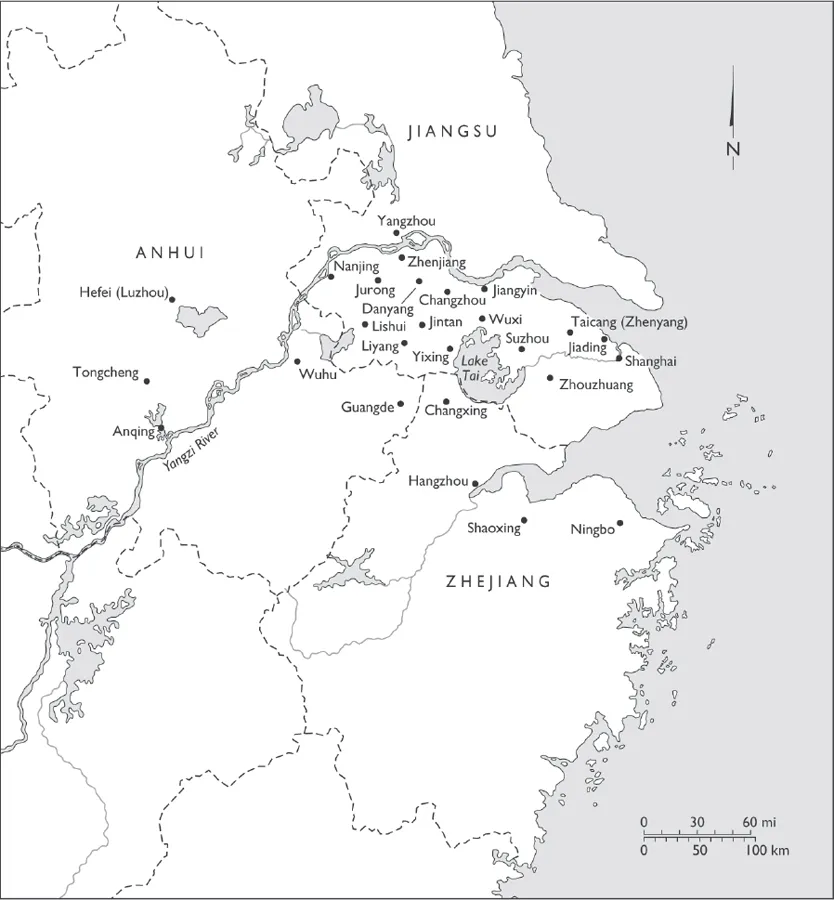

In January 1851, after winning a decisive battle against government forces, Hong Xiuquan pronounced himself the Heavenly King (Tianwang) of the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom (Taiping tianguo), an act tantamount to secession. The Taiping army fought its way northward out of Guangxi, seizing strategically important cities along the way. Rumors proliferated, spreading anxiety and uncertainty downriver to the Yangzi delta region and beyond.11 The Taiping forces occupied Nanjing in 1853 and made the early Ming capital their own, renaming it the Heavenly Capital (Tianjing). They established a currency and an independent calendar, promoted their religion, and imagined a radically new system of government and land tenure, which they were never fully able to implement. They also organized the populace into productive and fighting units, segregated by gender.

The Taiping played upon incipient Han nationalism: their propaganda quite literally demonized the dynasty, using the prefix yao, meaning demon, to delegitimize the Manchus as well as imperial personnel and institutions. They deliberately slaughtered the civilian inhabitants of Manchu garrisons.12 For eleven more years, in spite of internal dissension that nearly destroyed them, the Taiping fought against Qing armies, local militias, regional armies, and foreign mercenaries for control over territory and tax revenue.13 Communities changed hands, often repeatedly, inflicting terrible collateral damage on civilian populations and the infrastructure that supported them. Over the course of fourteen years, the war afflicted some sixteen or seventeen of the twenty-four provinces in the Qing Empire, wreaking particular havoc along the Yangzi River.

With the collapse of the Great [Qing] Jiangnan Encampment (Jiangnan daying) near Nanjing in 1860, the Taiping succeeded in occupying many of the major cities of the fertile and commercialized Yangzi River delta. Endemic warfare in the region between 1860 and the fall of the Heavenly Capital to the Hunan Army in 1864 led to catastrophic material and human consequences. The Qing and their allies also deliberately dehumanized their enemies. Zeng Guofan, the founder of the Hunan Army, described the Taiping as the enemies of Confucian civilization even as he prosecuted an eradication campaign against them.

Figure 1.1. The Jiangnan region

Refugees from delta cities fled to the countryside or sought safety in the treaty port of Shanghai, which benefited from foreign protection and which was in turn transformed by these new arrivals. Armies swollen by captives and new recruits contributed to escalating violence.14 Looting became imperative in order to feed the expanded armies and militias on both sides; and because civilians might also be soldiers or offer material support to the enemy, both sides brutalized ordinary people. As the war dragged on, the fighting became increasingly predatory, unpredictable, and chaotic.15 It also turned vicious as both sides called for annihilation of their enemies in ever more absolute terms.16 Alliances proved tenuous and property vulnerable. In some cases, brothers and neighbors fought on opposing sides, and many communities divided over whom to support and how best to protect themselves.17

In 1881, the editors of a local gazetteer for Wuxi County in southern Jiangsu Province observed that the war had shattered expectations of peace formed over the many centuries of Qing rule and marked the absolute end of an era: “While we urgently relied on the emperor’s efficacy to expel the wicked and odoriferous forces, several hundred years of protection were overrun, trampled, and at an end. The cruelty of the killing and destruction was unprecedented.”18

Why had things gone so badly wrong? The editors of the Wuxi gazetteer fault official incompetence and the venality of some of their counterparts among the local elite for the disastrous turn taken by events in their locale.19 Preparations for the rebel assault, they note, had been inadequate and incomplete and those in charge bore some responsibility. Worse yet, they add, there were those who collected taxes and rents that spring who not only failed to protect the county seat but also willingly turned over what they had collected to the rebels.20 Local militias that were mustered to fight against the Taiping had an appalling propensity to visit terror on farmers and merchants. Armies, short on rations, were difficult to control and maintain.21

There were also deeper and more insidious causes. The editors’ description of the antebellum situation is idealized in order to sharpen the contrast between the responsible rule and social harmony of the more distant past and the abject suffering of recent experience. But trouble had been brewing for some time because of a multifaceted social and political crisis that affected even the Yangzi delta, a region often described as China’s economic and cultural heartland. The empire was afflicted by shrinking government capacity, impoverishment, and natural disasters compounded during the Daoguang period (1821–1850) by the convergence of population pressure, failing infrastructure, corruption, inflation, and administrative malaise. These problems were much discussed at the time by statecraft-minded scholars.22 Additionally, widespread death and destruction had accompanied floods, epidemics, famine, and earthquakes during the first half of the nineteenth century.

Tensions were further exacerbated by a severe monetary crisis, which intensified during the 1840s and 1850s. The empire depended on a bimetallic monetary system whereby taxes and other large transactions were paid in silver denominated by weight, while most of the business of daily life was transacted in copper coins. A shortage of silver triggered a sharp rise in prices and an even more dramatic rise in land taxes. Landlords pressured tenants to pay their rents, so that they in turn could pay their taxes, along with the host of irregular fees that the bureaucracy had initiated in order to make up for its own shrinking fiscal resources.23 Tenants a...