![]()

1

Trauma, Colonialism and Post-Imperial Ideology

Introduction

This chapter explores two new concepts. First, through the exploration of trauma theory, it argues that the transformative historical event of colonialism in India and China can be classified as a collective trauma. Second, by changing the lens through which colonialism in India and China is viewed, it is possible to identify a “post-imperial ideology,” or PII.1 PII is rooted in a mentality of victimhood and is an essential component of both India’s and China’s national identity and, therefore, their international outlook. As subsequent chapters show, PII can then be used as an independent variable to analyze important foreign policy decisions taken by these rising powers.

Even a cursory examination of international politics demonstrates the ubiquity of colonialism and its effects. Despite the dismantling of the colonial empire more than half a century ago, the legacy of colonialism has played out in dramatic and tragic fashion. From the ongoing war in Iraq to the persistence of the Israel-Palestine violence to the territorial dispute in Kashmir, many continuing conflicts today are heavily influenced by the vagaries of colonialism.2 The impact of colonialism on economics, history, politics and culture has been widely discussed and dissected, and details of its brutality and exploitative nature have been explored. Yet, surprisingly, given the amount of ink devoted to the subject, there has been little systematic treatment of colonialism. This book argues that colonialism can be seen in two lights simultaneously. It is both a collective historical trauma and a causal variable that continues to influence the international outlook of states decades after decolonization. Viewing colonialism in such ways is new to the study of international politics.3

The concept of colonialism as trauma is particularly true for India and China, which attach immense significance to their colonial past. India and China underwent very different experiences of colonialism. Yet the “intensity” of this experience was similar for the two countries—both India and China regarded and responded to colonialism as a collective historical trauma. As a result they have a self-definition of victimhood. By this I mean, they believed themselves to have been victimized, and, as a consequence, adopt the position of victim in their responses to international issues even today.

As such they have a dominant goal of victimhood: the desire to be recognized and empathized with in the international system as a victim. The goal of victimhood carries with it a corresponding sense of entitlement that manifests itself in two subordinate goals: maximizing territorial sovereignty and maximizing status. The dominant goal of victimhood driving the subordinate goals of territorial sovereignty and status constitute a “post-imperial ideology” (PII) that influences international behavior. While PII affects a range of state behavior, its influence is most apparent when states perceive threats to sovereignty, when borders viewed as non-negotiable are contested or when a state’s international prestige is jeopardized.

Particularly, it does so by leading states traumatized by colonialism to first, adopt the position of victim and cast other states as victimizers; second, justify their actions or stances through a discourse invoking oppression and discrimination; third, adopt strict concepts of the inviolability of borders; and fourth, have a sensitivity to loss of face and a desire to regain “lost” status. Any analysis of India and China as rising powers is incomplete without taking into account this past that continues to shape their international outlook.

This chapter first discusses the impact of colonialism as a transformative historical event before briefly detailing the different experiences of colonialism in India and China. It then moves on to discuss trauma theory and how colonialism in India and China can be viewed through the theoretical framework of collective historical trauma. Finally, it discusses the three goals of PII and their emergence in state discourse and behavior after decolonization.

Imperialism and Colonialism: A Transformative Historical Event

I define a transformative historical event as an event which can either lead to the creation of a new state or can reshape an existing state by altering key political and military institutions and the ideology thereof, that are intrinsic to the state. The decolonization of Asia and Africa in the 1940s, 50s and 60s led to the creation of new states as well as the complete transformation of existing states by changing their pre-colonial political and military institutions. Post-colonial states such as modern India and China were, as I will discuss, radically different from their pre-colonial form. In this way, imperialism and colonialism were a transformative historical event.4

Imperialism and colonialism are terms that are often used interchangeably. The concept of imperialism has been elaborately defined by writers: from Hobson and Lenin, who viewed it as a metropolitan initiative driven by the profit motive, to Doyle, who termed it “a relationship, formal or informal, in which one state controls the effective political sovereignty of another political society . . . [that] can be achieved by force, by political collaboration, by economic, social, or cultural dependence.”5 Colonialism, a more difficult concept, is seen as a subset or outcome of imperialism.6 My theory refers to the transformative historical event of modern “imperialism and colonialism” taken together as a whole, and is concerned with extractive colonialism rather than settler colonialism. Extractive colonialism transformed pre-colonial societies, while settler colonialism often displaced them with populations from elsewhere.

Under extractive colonialism the colonizing power established an “extractive state” whose purpose was to shift the resources of the colony to the colonizer, often with few to no protections for the native populace against abuse by the colonial authority.7 Extractive colonialism came in different forms in different societies, but elements of these institutions had a striking resonance for all countries that experienced them: external political dominance, economic exploitation, denial of rights, and suppression of cultural and ethnic pride.

The demise of extractive colonialism was directly linked with a radical change in the normative structure of the international system.8 The colonial system was severely criticized and, as Jackson puts it, “lost its moral force” in the face of the ascendant “normative idea of self-determination.”9 Crawford similarly argues that it became unacceptable for states to keep colonies because it was “wrong to deny nations and individuals political self-determination.”10 Not only was independence now a basic right, but colonialism was “an absolute wrong”—“an injury to the dignity and autonomy of those peoples and a vehicle for their economic exploitation and political oppression.”11 Through textbooks, cultural and social discourse, international conferences like Bandung in 1955, biographies and newspapers, the newly independent states would view their experience of extractive colonialism through a prism of victimization, suffering and endurance. Effectively, as I will discuss, this experience was a collective trauma.

It is important to discuss briefly the history of colonialism in India and China prior to demonstrating that both states encountered similarly “intense” experiences of colonialism that met the standard of collective trauma.

A History of Colonialism in India and China

For modern India and modern China, there was and is a strong distinction made between the previous rule of the country by various dynasties, some of which had external origins, and the later influx of colonial powers from the West and Japan.

In India, the pre-British dynasties of the Delhi Sultanate and the Mughals were not termed “colonizers.” Rather, the history of India up until the British period, and the encounter with the English East India Company,12 is one of assimilation of and accommodation with the waves of foreigners landing on its shores. There was no “clear distinguishing line between Islamic civilization and the pre-existing corpus of ‘Hindu tradition,’” and, in fact, “creative Indo-Islamic accommodations of difference were worked out at various levels of society and culture.”13 Even the first Europeans to set up a base in India—the Portuguese led by Vasco da Gama in 1498—“settled within the structure and were, in a way, swallowed by it.”14 What the advent of British rule brought was a clear line drawn between the natives and the outsiders, and the need for the country to adapt to the modern world.

The transition to colonial rule in India took place in the mid-18th century with the gradual dismantling of the Mughal empire. The English East India Company upon arrival in the seventeenth century was a petitioner that sought the right to trade from the Mughals and obtained permission to do so from Emperor Jahangir in 1619. In 1757, the Company took the first major step toward the establishment of British colonial rule in India by defeating Sirajud-daula, the nawab of Bengal, at the Battle of Plassey. The Company, whose political and military power had hitherto been limited to a few factory forts in coastal areas, had been competing for turf with the French East India Company. The nawab had objected to the Company’s building fortifications in Calcutta to ward off the French. The victorious British acquired vast rights to operate in the nawab’s domain, concessions that enriched Company coffers and prepared them for the Battle of Buxar in 1764, where they decisively defeated the combined armies of the nawabs of Bengal and Awadh and the Mughal emperor. This victory forced the Mughal emperor to grant them the diwani, the right to collect the revenues of Bengal.

The East India Company’s new financial and military strength gradually enabled them to extend their rule over the subcontinent. In 1857, a widespread revolt against British rule erupted. When it was crushed by the British at great expense, the Crown decided to dissolve the East India Company and instead rule India directly through a Viceroy governing as the Crown representative, a system that would remain until independence and partition in 1947.

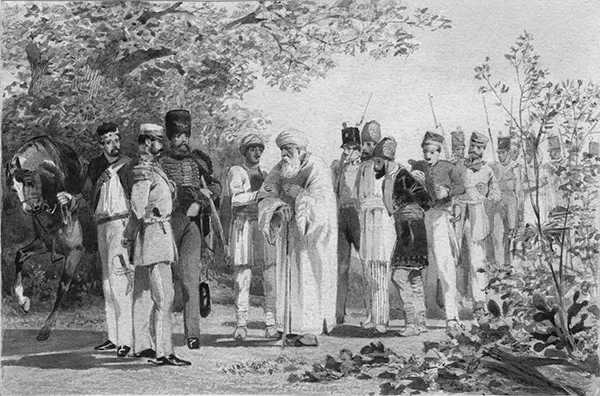

FIG. 1.1. Capture of the King of Delhi, 1857–58. Source: Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library.

Post-1857 saw the rise of organized anti-colonial nationalism motivated by the belief that a hundred years of British rule had already, economically and politically, crippled the country and, thus, demanded a movement to regain India’s sense of worth. The early strands of the nationalist movement eventually gave way to Gandhian tactics and the dominance of the Indian National Congress.

In Chinese historiography, too, the beginning of the modern period is marked by a clear border between the previous conquests of China and the influx of the Western powers and Japan (bitterly termed yang guize, or foreign devils) into China. Paine states that history books present the modern period as “beginning with the defeats in the Opium Wars followed by a century of uninterrupted concessions and humiliations before foreigners.”15 It has been suggested that the Qing were in fact colonizers. The Qing were, after all, Manchus who conquered the existing Han Chinese population, and proceeded to ban Han Chinese from holding high government posts or intermarrying with the Manchus. Dissenters counter that the Qing carefully upheld Confucian structures and Chinese traditions in order to emphasize their claim to “the Mandate of Heaven” (tian ming). Paine remarks, “[M]odern history marks the first time that China had ever been completely unable to sinicize the outsiders but had instead been forced, however reluctantly and painfully, to adapt to the world beyond China.”16 Arguments about the nativization of the Qing notwithstanding, there is no doubt that the Chinese nationalist movement, though critical of the corruption of the dynasty, not only embraced the territorial boundaries and legacy of the Qing but also had an anti-foreign powers doctrine at its core. This trend continued even when the Guomindang was replaced by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Thus, the Chinese see the modern history of colonialism in China as two-pronged—the carving up of Qing China into foreign spheres of influence by Western powers and Japan (1842–1905), and the later domination by Japan during World War II (1931–45). Both phases of imperialism have strong resonance for the Chinese and are collectively remembered as the “century of humiliation” (bainian guochi). Indeed, Mao referred to China during this period as ban zhimin di, or, a semi-colony.

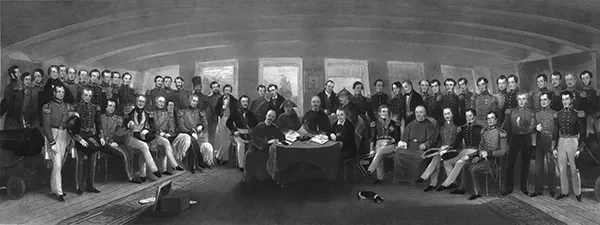

FIG. 1.2. The Signing and Sealing of the Treaty of Nanking, F. G. Moon, 1846. Source: Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection, Brown University Library.

The insulated Chinese empire’s first brush with European powers occurred through Portugal’s merchants in the Far East in the early sixteenth century. “The Chinese did not realize the significance of the Portuguese arrival, but it initiated a process that would end by destroying the Empire and engulfing China.”17 The first British trading ships entered Guangzhou (Canton) circa 1637, and between 1685 and 1759 the English and other Europeans traded at several places along the Chinese coast, including Xiamen, Fuzhou and Ningbo.18 After 1759, Guangzhou was designated the sole port open to Europeans. The isolation of the Qing empire from the realities of the outside world meant that the trade with the British and Dutch East India companies was still “nominally conducted as though it were a boon granted to tributary states.”19

Ultimately, opium imports from India to China led to a crisis. Opium was produced in India and sold at auction under official British auspices and then taken to China by private British traders licensed by the East India Company. Opium sales at Guangzhou paid for the substantial tea trade to London. The reversal of the balance of trade and the drain of silver from China to pay for increasing imports of opium, combined with the societal effects of opium addiction, alarmed the Qing.20 The ensuing clash resulted in the Opium War of 1839–42, and China’s defeat in that conflict secured Qing agreement to the Treaty of Nanjing in 1842, substantially increasing British access t...