![]()

1

A Collaborative Model for Long-Term Investing

“The single most realistic and effective way to move forward is to change the investment strategies and approaches of the players who form the cornerstone of our capitalist system: the big asset owners . . . If they adopt investment strategies aimed at maximizing long-term results, then other key players—asset managers, corporate boards and company executives—will likely follow suit.”

THIS QUOTE BY MCKINSEY & CO. global managing partner Dominic Barton and Canada Pension Plan Investment Board CEO Mark Wiseman encapsulates what this book seeks to achieve. We focus our attention on the building blocks of the capitalist system, the large-asset owner-investors, and examine how they can more positively impact their own fiduciaries as well as the wider economy and society.

With the global population expected to increase to ten billion by 2050 and the proportion of people living in cities expected to double, the strain that this will place on existing infrastructure, housing requirements, farmland, and other natural resources will be profound. In order to avoid the effects of irreversible climate change, deepening inequality, and even military conflicts over resources, we will need to unlock large pools of long-term capital to fund resource and infrastructure innovation. We classify long-term investments1 as investments in illiquid, private-market asset classes such as infrastructure, clean energy, real estate, venture capital, agriculture, timber, and private equity that can produce attractive financial returns and, by their nature, can have significant impacts in the economy and wider society.

It is critically important for the health of our capitalist system and indeed the world that the global community of long-term investors begin investing in long-term projects that will help address our global challenges and prepare us for this future state. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the community of long-term investors has more than $100 trillion in assets under management,2 which means there should be plenty of capital available for the costly economic transitions ahead.

The significance of long-term investing for large institutions has risen to prominence after the drawbacks of short-termism and myopic behavior were exposed in the financial crisis of 2008–2009. The crisis highlighted badly misaligned economic incentives; the poor performance of highly leveraged, complex financial institutions; and a lack of value-add from the short-term-oriented financial services sector. Financial regulation since has attempted to provide reform for long-term stability and restore discipline in the market place. Such changes in behavior are crucial for megabanks but also for the largest holders of capital, typically asset owner institutional investors located around the world.

So who are these long-term investors and what are their characteristics? Institutional investors or asset owners3 such as sovereign wealth funds, endowments, foundations, family offices, pension funds, and life insurance companies have long-term profiles and can be separated from mutual funds, private-equity firms, and other asset management firms that invest on behalf of the institutional investors, sometimes criticized for their more short-term-oriented behavior. Sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) are institutional investors set up by governments and are usually funded by budget surpluses to provide long-term benefits to a nation.4 Pension funds provide retirement payments for pension scheme members and consist of either defined-benefit or defined-contribution systems. Defined-benefit plans are required to pay a certain amount to their beneficiaries at a certain time in the future. Defined-contribution plans, instead, are based on contributions and the performance of investments to generate a retirement annuity for plan beneficiaries. Life insurance companies are considered long-term investors because of their requirements to pay beneficiaries or policyholders in the future. Endowments/foundations are used to fund the expenses of nonprofit organizations and generally have a mandate to exist in perpetuity, providing a steady stream of income to their beneficiaries. Finally, family offices manage the wealth of high-net-worth families and have the mandate to manage wealth for future generations of family members, requiring a long-term outlook for investments.5

Sadly, even with the large amounts of long-term capital available, the mobilization of long-term investors (LTIs) toward long-term projects is not happening. We still have widening gaps in infrastructure and energy innovation financing. The patient investors needed to support the capital-intense, long-development ventures and projects that could, for example, reduce greenhouse gas emissions at scale simply are not there. We recognize that it is not an investor’s job to solve climate change or fix our infrastructure, but it is the fiduciary obligation of a pension fund or endowment to maximize financial returns. Investing in these long-term projects in the right way has shown to be financially rewarding.6 There may be an abundance of LTIs, but for a variety of reasons, most LTIs are not exercising their long horizon.

This is partly because the investment management process involves many parties and intermediaries, such as asset managers, placement agents, and consultants. These intermediaries provide expertise in information gathering and scale advantages in investment costs. However, the multiple layers of intermediation can also create agency conflicts and misalignment of objectives. If institutional investors delegate the asset management to intermediaries in order to shift responsibility and reduce perceived risk, they then violate their fiduciary duty and may not be acting in the best interest of their beneficiaries.7

In the case of infrastructure, the situation is quite paradoxical. Most governments around the world are sitting on a large backlog of infrastructure projects that they are unable to fund effectively. And yet the same governments are also often in control of large pools of pension or sovereign assets that they struggle to invest effectively. Clearly, there are bottleneck issues around the way in which the largest long-term sources of capital in the world are intermediated with the long-term projects that are most in need of investment. A lot of the funding has to come from “off-balance-sheet” transactions for these governments, as many do not have the capability to fund the projects because of already high debt levels. While pension funds and sovereign funds have a primary commercial objective, we argue that their long-term characteristics make them more amenable to achieving wider long-term economic and social goals, compared with short-term-oriented, opportunistic types of investors such as certain asset management firms. On top of this, if pension funds and sovereign funds do achieve their long-term financial objectives, it is likely that these benefits will accrue back to the citizens of governments that need the funding. This book tries to address how more of these benefits can be enjoyed by asset owners rather than be disproportionately swallowed up by opportunistic financial intermediary firms.

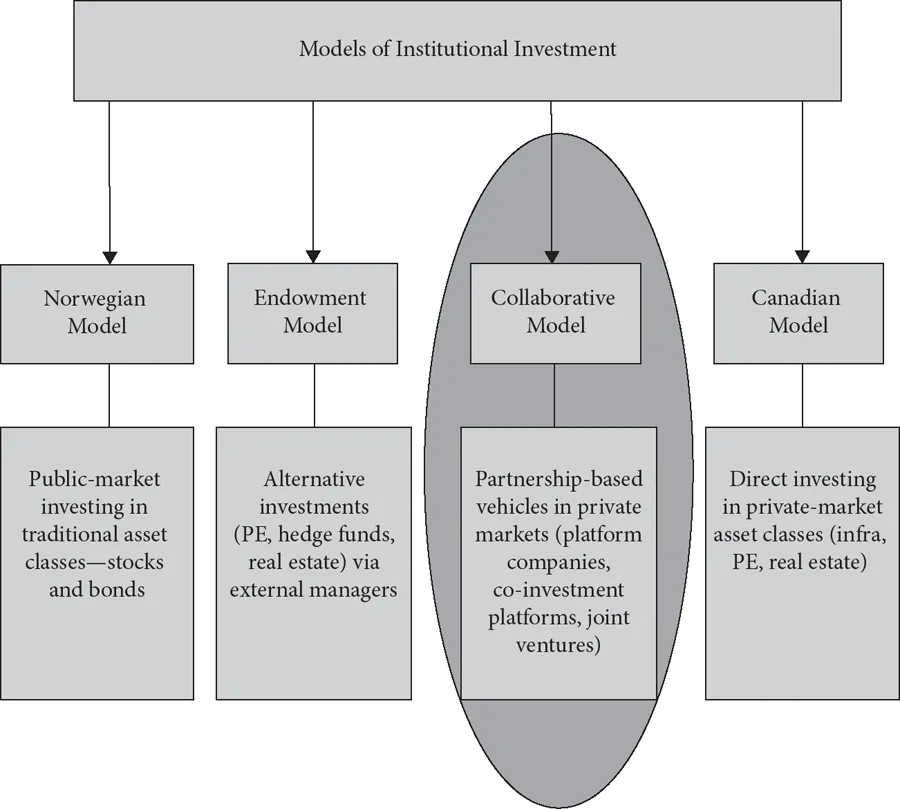

There is ample academic and empirical evidence to show that institutional investors that are able to invest directly into private assets can outperform those that delegate their asset management function to external intermediaries.8 There is also evidence to suggest that allocations to private-market assets can have significant benefits to institutional investors.9 As a result, many investors are looking to increase their allocations to private markets. Given these trends in the industry, this book looks at how institutional investors can access private-market assets in the most efficient way possible. In essence, the book argues for and provides the premise for the collaborative model of institutional investment. Such a model is based on institutional investors developing an efficient and effective network to form long-term relationships with trusted investment partners. The collaborative or partnership-based model of institutional investment combines aspects of the Canadian direct investing model and the David Swensen–pioneered endowment model of investing in private market assets10 with some new collaborative mechanisms and strategies. This is depicted in Figure 1.1. We use the term re-intermediation to explain the rationale behind the collaborative model of long-term investing. Three main components to the re-intermediation thesis are proposed here:

First, as has been mentioned (and backed up by the literature), institutional investors that can in-source investment management services and make direct investments should do so. The universe of direct investors has been increasing steadily as a result of greater inflows of assets and the realization that their process can be more efficient.

Second, while financial intermediaries have gained excessively in the past at the expense of many institutional investors, the financial services industry has been established for a significant period of time, and substantial value has been created by a number of these organizations providing the services of fund placement, asset management, consulting, and advising. As Warren (2014) states: “the asset management industry has been a source of economic growth, as a valuable intermediary in the savings-investment channel.” The second aspect of the re-intermediation thesis is thus focused on constructive engagement with intermediaries. Investors that cannot invest directly should engage with intermediaries in a novel way to ensure that the interests of asset owners are more aligned with those facilitating the deployment of capital. Specifically, this alludes to asset managers, fund of funds, consultants, and placement agents restructuring their business models to ensure that they are adding real value to the investment management process in a transparent, honest way.

FIGURE 1.1 The collaborative model of long-term investing

Third, co-investments made by specific-purpose vehicles or platforms where peer investors come together to invest is also part of the re-intermediation process. The idea here is to bring like-minded investors together in a club or joint venture arrangement with a specific mandate to invest collaboratively into certain assets. Although some sophistication would be required among co-investors to be a part of such a vehicle, these initiatives may allow slightly smaller investors to gain access to private-market deals in a much more aligned way than through the fund manager route.

Central to the re-intermediation thesis is the need for investors to form an effective, efficient network to facilitate investments into the informationally opaque private-market asset classes. This involves developing strong relationships with peer investors as well as with intermediaries and other parties to form aligned investment partnerships that help achieve the objectives of the investment management process. In order to analyze these interorganizational dynamics at play, we draw on sociology theory to support the arguments in this book.

While the intention here is not to be an academic textbook, we use economic sociology theory to illustrate the importance of investors building their network. Economic sociology theory is also used to inform investors of how a more relational, transparent form of governance can be achieved with their intermediaries. We then provide case studies of how innovative partnership-based vehicles are being set up by institutional investors to illustrate how investors can get closer to the assets of interest.

The Value of Long-Term Investing

Institutional investors that exercise their long-term investing capabilities can add significant value to society and the wider economy. Long-term investors can have positive influences on individual businesses by realizing long-term value creation and improving their longer-term prospects. Theoretically, they can provide liquidity during critical times and help stabilize financial markets. When acting in a long-term manner, they are not prone to herd mentality and can retain assets in their portfolios in times of crisis, and in this way play a countercyclical role.

While this book is predominantly focused on private-market investing, the drawbacks of short-termism for an institutional investor can be seen through the returns of the U.S. stock market. As indicated in Figure 1.2, the S&P 500 since 1970 has grown in value a hundred times over. However, between 2000 and the end of 2009, the return of the market was in fact negative (–0.3% nominal, –3.0% real). An investor that held stocks for the whole period compared with just between 2000 and 2009 would have reaped significant benefits.

Figure 1.3 illustrates how short-termism has crept into the investment decision-making process for investors with the average holding period of stocks declining significantly over the last 50 years. This is true for most stock indices around the world:11

The Harvard Management Company (HMC), which is responsible for the investment of Harvard University’s endowment fund, illustrated how institutional investors can be crippled by short-termism. In the 2008–2009 financial crisis, because of the lockup of its capital in risky derivative instruments offered by external asset managers, HMC faced a liquidity crisis to cover its operating budget. As a result, HMC was forced to sell a number of its stakes in illiquid asset classes at large discounts, resulting in large losses for the endowment. In this w...