![]()

Chapter 1

LEARNING IN THE VUCA ENVIRONMENT

THIS CHAPTER BUILDS on the information presented and discussed in the Introduction by examining the proximal and distal contexts in which peer coaching takes place and how peer coaching relationships are both embedded in and shaped by these environments. We examine peer coaching as a relatively new and low-cost resource to address the lifelong learning needs of individuals and organizations. Peer coaching is a powerful tool with remarkable properties: high impact, just-in-time, self-renewing, low cost, and easily learned.

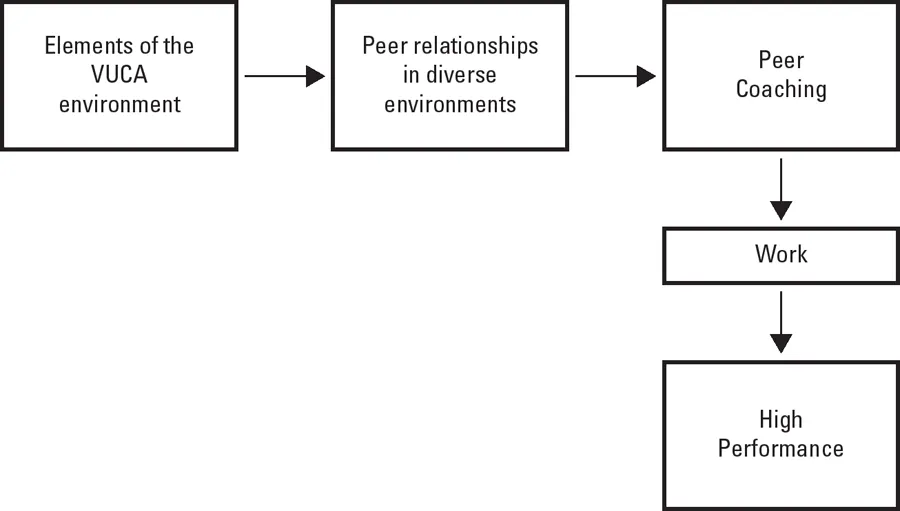

The U.S. Army and others describe the environment in which all work takes place and work relationships exist as a VUCA environment (see Figure 1.1). We all work in a turbulent world that is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous. Thomas Friedman describes the rate of change in this environment as “dizzying acceleration.”1 Consequently, there is an ever-increasing demand on individuals to grow continuously and pressure on organizations to adapt successfully.

FIGURE 1.1 Peer Coaching in the VUCA Environment

But wait, the situation is even worse than Friedman’s description would suggest. Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey argue that we are losing the battle to adapt to VUCA:

In . . . the VUCA world—a world of new challenges and opportunities—organizations naturally need to expect more, and not less, of themselves and the people who work for them. But our familiar organizational design fails to match that need. [The result is that] . . . in an ordinary organization, most people are doing a second job no one is paying them for. [M]ost people are spending time and energy covering up their weaknesses, managing other people’s impressions of them, sowing themselves to their best advantage, playing politics, hiding their inadequacies, hiding their uncertainties, hiding their limitations. Hiding.2

So, as Kegan and Lahey point out, not only are we losing the adaptability battle, we are also wasting precious resources in the process. Organizations are paying a full-time wage for people who are essentially working part time at their real job (while the rest of their time is wasted covering up their limitations), and employees are burning out at the same dizzying rate as the acceleration of change. This failure of organizations and individuals to learn on the job represents a highly inefficient work process.

So, what is to be done? Friedman concludes that nations and individuals must develop the capacity to be fast (innovative and adaptable), fair (ready to help others who suffer in this environment), and slow (seizing everyday opportunities to shut out the noise, be mindful, and get in touch with their deepest values). Friedman provides a personal example of how relational influences can aid learning (unintentionally, in this case!). He meets routinely with various policy and thought leaders in Washington, D.C., for breakfast as part of his own strategy for learning. (This practice provides the dual advantages of helping him learn and avoiding eating alone.) Given the vagaries of rush-hour transportation in the busy U.S. capital, his sources are sometimes late. One time when his guest apologized for this, Friedman became aware of how useful that unexpected free time had been for his own personal reflection and he responded, “Oh, no apology necessary. Thank you for being late!”3 (And, voilà, there was the genesis of his latest book!)

Learning relationships, especially when the other party is intentionally trying to help, can be an important means of developing the fast, fair, and slow capabilities required to deal with this dizzying acceleration. This is where peer coaching comes to bear.

Robert Johansen agrees that surviving and thriving in this chaotic environment calls for fast and continuous learning.4 Individuals, teams, and organizations need to develop positive VUCA responses to the malevolent VUCA qualities in the accelerating environment. They need to have vision, understanding, clarity, and agility. Relationships are crucial for developing each of these adaptive qualities. Peer coaching can support people in developing the capacity to strengthen all four adaptive VUCA qualities. Let us consider each of these in turn.

First, consider volatility. The adaptive response to volatility, vision, at its best, is a collaborative activity. As more people try to make sense of a complex environment, as more eyes look at it, the likelihood that the collective will perceive things accurately increases. Furthermore, engaging with volatility requires staying centered and being guided by personal vision, principles, and practices.

The necessary learning in this VUCA environment requires the capacity to create personal vision that aligns with a greater purpose, clarity, understanding implications of macro/micro changes, and agility. The turbulence associated with volatility can disrupt one’s sense of direction and create a sense of imbalance. Peer coaches can support each other in staying oriented by helping the other person fully take in what might be causing disorientation, thus helping clarify and strengthen their peer’s center.

In addition, creating a personal vision aligned with a greater purpose means that two visions are in play. One is the vision of what the environment of the future will be both inside and outside the organization: the external vision. The other is the individual’s personal vision of his or her own individual future: the internal vision. Aligning both the internal and the external vision is important, and a peer coach can be extremely helpful as a person thinks through how best to create this personal alignment.

Understanding is the personal quality that provides an antidote for the uncertainty in VUCA, which entails making meaning out of many and diverse signals. This requires integrating numerous complex data points. Many heads improve the quality of the understanding by helping to discern patterns in complex inputs, see trends over time, and separate signal from noise. The parable of the blind people and the elephant comes to mind here. It takes time for six separate people to figure out that all of the different shapes—the hoselike trunk, the flat floppy ear, and the bristly hair—are all part of the same animal. Through raising effective questions about what each is experiencing, deep active listening, and combining separate inputs to brainstorm answers, the blind people can gradually converge on a more informed and accurate conclusion about what they have encountered. They gain clarity.

The adaptive response for ambiguity, agility, for teams and organizations requires many entities to coordinate actions. The better the communication among these entities, the more agile will be the response. Learning to cope with uncertainty is easier when peers seek understanding by reflecting together and clarifying possibilities and options rather than by relying on one person’s experiences. Because there is a necessary trial-and-error aspect in trying out different responses and learning through experience, some responses will be wrong. In peer coaching, the coach can provide psychological safety and support while helping boost the person’s confidence to “hang in there” and keep trying. Getting help from others can be a quick and easy way to expand one’s repertoire for responding to new challenges.

Learning as a Lifelong Process

One of the challenges that managers face is how to promote learning, growth, and development for themselves and others. Life span issues of adulthood mean that career learning has moved from a one-off education activity to an ongoing lifelong process that underpins a range of career education issues including preparing for the world of work, transitioning to a job, perhaps losing work, and adjusting to changed circumstances.5 Learning and work have traditionally not been well linked. Kegan and Lahey point out that learning and development activities at work are typically seen as “something extra—something beyond and outside the normal flow of work, an approach that raises the vexing problems of transfer and cost.”6 Now, they must integrate into a continuously supportive process so that people can learn in their everyday work the knowledge, values, skills, and understanding they will require throughout their lifetimes. Oral and written communication skills, motivating and managing others, and leadership skills contribute to improving workplace situations.7

A key feature of lifelong learning activities, such as peer coaching, is to ensure that they are self-initiated and independently conducted. When someone is trying to make sense of a newly assigned project task, it is unlikely that a person in a position of power will say, “OK, now get together with a partner and work together as peer coaches to help each other solve this problem.” The two individuals will need to know what peer coaching is, know how to do it well, and be willing to initiate a peer coaching relationship. They also need to be able to increase their skills in peer coaching and “learn how to learn.” Indeed, learning ability is a key career competency in the contemporary business environment.

Such skill development is inherent in professional and career education today, and degree programs are frequently seen as the foundation for acquiring and developing these skills. An increasing number of workers are returning to tertiary institutions at various stages of their lives to address dramatic changes in work roles.8 However, reviews of management education have been critical of business schools’ lack of responsiveness to employers’ needs and desires.9 The current attention that accreditation bodies pay to demonstrated links between the learning process and outcomes as measures of quality (e.g., AACSB and EQUIS) underscores renewed emphasis on the process of learning, rather than content knowledge.

In the last decade, both scholars and practitioners have acknowledged that mentoring and other developmental relationships are essential to helping individuals strengthen their ability to learn at a pace and breadth that is required in today’s workplaces.10 These developmental relationships exist in a variety of forms, both inside and outside organizations,11 and are well documented as a key to successful learning in careers.12 The most well recognized is the traditional mentoring relationship in which a more experienced colleague supports a younger person through assignment allocation, feedback, and sponsorship.13 Positive career outcomes and psychosocial support emerge in the process.

While traditional mentoring continues to be an enduring learning process,14 confusion arises from the plethora of terms used to describe developmental relationships and the lack of clarity associated with them.15 Mentoring and coaching are the most widely recognized terms, and organizations use both forms frequently. These labels are sometimes used interchangeably and, although some argue that they denote the same thing, the meanings can be easily confused.16 In addition, many more forms of developmental constructs are identified by other names.

Regardless of the terminology, the resource constraints of contemporary organizations include relational limitations. Therefore, fewer senior managers are able to act as mentors.17 And even those senior managers who are willing and able to act as mentors may not always be relevant sources of learning to younger employees since the experiences of these seniors took place in a world that is quite different from today.

What is the upshot of all of these forces? There is an extremely high need for emotional and informational support for all workers as they strive for continuous learning to maintain their career adaptability and other key capabilities. This need is largely unmet, but one answer could be the increased use of assistance from peers through peer coaching. Thus, the process of peer coaching represents a new application of a developmental interaction that focuses specifically on accelerating career learning.

Peer coaching builds on the fundamental premise of a helping relationship with the intent of promoting the other person’s growth, development, maturity, functioning, and coping with life.18 Whereas helping relationships have often been relegated to therapy, the lexicon of organizations and careers has broadened to include a wider scope of “helping” possibilities. Peer coaching is an example of this expansion.

Embedding Peer Coaching in the VUCA Environment

The VUCA environment demands peer coaching, as it is one of the best ways to adapt to the incredible demands of VUCA. In this book we demonstrate that peer coaching supports the development of the four adaptive responses of vision, understanding, clarity, and agility.

VUCA highlights the potential for peer coaching in two ways. First, the environment moves so quickly (volatility) that the ability to adapt and solve problems quickly is indi...