![]()

Part 1

Production

![]()

Chapter 1

The Good Shepherd and His Flock; the Approach to Sheep-Farming 1100–1600

Sheep were probably first domesticated in England around about 4000–3500 BC during the Neolithic period and by Roman times were commonly found on most farms providing wool for home-spun clothing, milk for making cheese and meat. There may have been as many as 7.5 million sheep peacefully grazing English pastures by the time the great inquest of property and ownership was compiled in what became Domesday Book, perhaps outnumbering the people by more than two to one.1 As the trade in wool became more widespread and more profitable, the management of sheep became a matter of some importance for many landowners and their tenants. It was not essential to life in the same way as grain farming, but it held out prospects of an increase in riches even as early as the beginning of the twelfth century.

Contemporary writing

There are, however, very few treatises or any other kind of writing from this period which give any but the barest details of the way to care for sheep. This was the kind of knowledge which was part of the common stock of country folk; recording it in writing would have seemed impractical and a waste of time to most people. It was neither exotic nor rare but utterly commonplace; writers, mostly clerics at least before c.1350, were not often concerned with such mundane matters, while few shepherds if any would have been able to read or have access to texts like this. Those who were literate left such things to their servants. In England, however, there is a very small group of treatises, most of which date from the end of the thirteenth century, which deal with agricultural matters. Landowners were becoming much more interested at this time in having some idea of the profitability of their holdings and where and how income was generated; for this reason, they needed guidance on how to keep and understand accounts. Advice on keeping accounts and recording the yields, whether in money or in produce of both arable and livestock farming, led to some discussion of the best methods of producing the best returns.

Another motive for a more systematic approach to land management was the increasing influence of statute law on land holding, especially laws introduced during the reign of Edward I. Manorial extents which listed and valued all the assets of a manor also became much more frequent particularly after the Extenta Manerii was issued by the Crown, a document asking detailed questions about a manor and its produce intended to provide the basis for the valuation of land holdings.2 These treatises were intended not so much for the lords of large estates but for the lawyers and bailiffs employed on this kind of property, men who did not have a university education but the kind of practical training found in the Inns of Court. It is doubtful if they were ever read by agricultural workers themselves.

The earliest of the group, from the last decades of the thirteenth century, is known as the Seneschaucy. Its main aim was to set out clearly the duties of each official or servant on a manor, including the shepherd. This was taken as a model and much of its content incorporated in a work known as La Dite de Hosebondrie or Husbandry, originally written in Norman French, which dates from sometime after 1276. This work had quite a wide circulation. There are more than 34 MS copies in existence while it was also printed and translated into English as early as the late fifteenth century. The introduction states that it was written by one Walter of Henley. He had clearly had experience as a bailiff on a large demesne3 estate and later became a member of the Dominican order. His book describes the way in which a large estate, where the demesne lands are managed by a bailiff on behalf of the landowner, should be run.

His book was, in fact, for all ‘who have lands and tenements and may not know how to keep all the points of husbandry, as the tillage of land and the keeping of cattle’.4 Much of his material also appears in a work called Les Reules Saynt Robert to which the name of Robert Grosseteste, the scholar and bishop of Lincoln, was attached.

The Seneschaucy, the model for Walter’s work, has a special section on the work expected of a shepherd. His prime duty was to guard the sheep from attacks by dogs, and to prevent them straying into dangerous bogs and moors. He and his watchdog must spend the night ‘in the fold with the sheep’. Sheep were clearly enclosed in a fold made of hurdles every night with, on large estates separate folds for the wethers, (castrated male sheep) the breeding ewes and the hoggs or hoggets (female sheep which had not yet lambed). One shepherd could be expected to look after either 400 wethers, 300 ewes, or 200 hoggs. He must be of acknowledged good character, even, the Seneschaucy states, if he was friendly with the miller (notoriously the most prone to fraud of all manorial servants.) He must not leave the flock ‘to go to fairs, markets or wrestling matches or to spend the evenings with friends or go to the tavern’. He must reliably and faithfully account for flock numbers and any losses by death or disease.5

Walter of Henley’s work does not go into any more details regarding the work of the shepherd apart from recommending that the he must treat the sheep well.

‘Looke that your sheapherd be not testye (angrie) for thorow anger some of the shepe may be harassed wherof they may die Looke wheather your sheape goe feading with the shepheard going amongst them for if the sheepe goe shunning (avoiding) him it is no signe that he is gentle unto them’.6

Other aspects of the care of sheep are not mentioned. One of the main benefits of having a sheep flock on a manor, however, was the fertilising effect of sheep folded on arable land before it was sown. He says,

Also the folded land (lande that is doung with the folde) the nearer that it is to the sowing tyme the better it is. And from the first ladie day [15th August] cause your folde to be pitched abroade (according to the number of your sheep) be it more or lessse, for in that tyme they carie out no (the sheep make much) doung.7

Apart from this he lays most emphasis on the use of ewes’ milk for making butter and cheese. In his view 20 sheep fed on the rich pasture of a salt marsh should produce in the summer as much milk for butter and cheese as two cows while for those pastured on fallow land or less rich meadows 30 sheep will produce as much as three cows. Wool production is treated as something of a sideline, coming largely from sheep which are sold for meat or who are culled from the flock.8

A much more detailed discussion of the best way to care for sheep can be found in Le Bon Berger by Jean de Brie.9 De Brie apparently rose from being a goose herd in the French countryside to being in the service of Arnoul de Grant Pont, treasurer of the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, and later in that of Jehan de Hetomesnil, one of the royal councillors and a Master of Requests, as well as a canon of the Sainte Chapelle. A prologue to the surviving printed versions (there are four dating from c.1486–1542) states that Jean de Brie wrote the book in 1379 for presentation to Charles V of France. No MS version of the text has been found leading some to doubt that this is a genuine fourteenth century text. Some of it seems to reflect the religiosity of the period of the Reformation; the image of Christ as the Good Shepherd was a favourite at the time and appears in this text. The book also includes classical references which may be due to later editing of the printed text. On the other hand the book also speaks of the need for a shepherd to be ‘of good morals’ and to avoid taverns and all dishonest places, phrases which echo those of the two earlier English treatises which may have been known to the author.

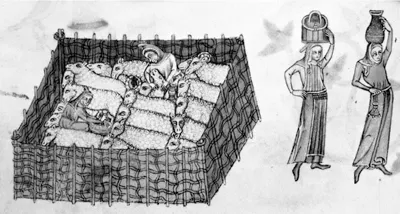

Figure 1. Milking folded sheep (The Luttrell Psalter: BL Add MSS 42130)

It also has in the main body of the work an eminently practical approach to the business of being a successful shepherd. It does, of course, relate to sheep-rearing practices in northern France; we cannot be certain how comparable these were to practices in England. Nevertheless much of the content would seem to have a wide application. The author lists the equipment a shepherd should have: a case of ointment to deal with the scabs of mange is essential, along with a knife to cut out the mites. He should carry a scrip with food for himself and his dog and also a leash for the dog and, of course, a crook with a hook for catching sheep by the leg when necessary. His clothing is also described, including a large felt hat which would be very good for keeping off the rain and which should include a large folded-back ‘pocket’ in the front. This was intended for the storage of any wool clippings he needed to show his master. Mittens, either knitted from wool or made out of cloth, were recommended for use in the winter. They could be hung from the shepherd’s belt when he needed to use his hands. Finally a shepherd might take a musical instrument with his flock into the fields, perhaps some form of flute or bagpipes.10 This may sound like some sort of pastoral conceit but illustrations of shepherds in the fields dating from at least the thirteenth century show shepherds playing wind instruments of various kinds.

In this book, a month by month calendar also sets out a schedule for a shepherd’s work. The writer takes for granted that the sheep were taken into a fold at night. In this instance a more permanent building, like the sheepcotes widely used in our period, was implied, not just an enclosure surrounded by hurdles, since opening doors and windows for good ventilation was often mentioned. The shepherd was also instructed about removing the dung; this must never be done in May but, on the other hand, it was very good to do this in December.11 The care of ewes in lambing time was set out in some detail. ‘Lambs dropped in the field were likely to be eaten by ravens, kites and crows’ if the shepherd was not rapidly on the scene. The shepherd ‘should not sleep too soundly at night’ so that he could deal with newborns. The writer’s own experience was plain as he described how the ewe cleaned and stimulated the newborn and how suckling should begin. He also had a lot to say about the plants on which the sheep should graze at different times of the year. For example gorse was a danger in March since it was ‘poorly digested’ and ‘very harmful to ewes in their throat’s gullet’. A shepherd needed to make sheep which had eaten gorse drink immediately to avoid further problems. Poppies, that is those ‘with a round leaf and red hairy stem’ made sheep ill in June. In September the flocks should feed on wheat stubble in the morning and oat stubble later in the day but ‘barren and rocky lands’ should be avoided because this was where something called mugue sauvage grew. This plant which had yellow flowers and a clover-like leaf infected sheep with a possibly deadly disease called yrengier. This is said t...