![]()

JONATHAN DEMME’S THE SILENCE OF THE LAMBS

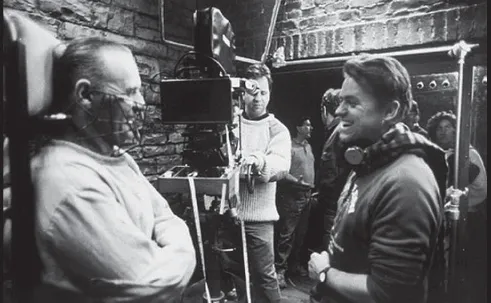

Jonathan Demme (right) shares a joke with a muzzled Anthony Hopkins

To say that director Jonathan Demme’s career has been chequered does not begin to do justice to a series of films that frequently bears the signature of a talented auteur but which, of late, appears to have been drained of all the things that once made his work so exhilarating and inventive. Like several other major American talents, his alma mater was the Roger Corman school of film-making, with the king of American exploitation movies giving him his first break. Unlike Francis Coppola, whose tyro venture for Corman was in in the horror field (the delirious, meaninglessly-titled Dementia 13 in 1963), Demme was given crime film assignments with healthy doses of sex (de rigueur for the canny Corman): Caged Heat in 1974 and the lively and accomplished Crazy Mama two years later. After Corman, his first major venture in the thriller field was the taut, Hitchcockian Last Embrace in 1979, but his real identity as a film-maker began to emerge in a series of genuinely quixotic and unusual films such as Melvin and Howard (1980), Swing Shift (1984 – compromised by the proverbial ‘artistic differences’ with its star and producer, Goldie Hawn) and the frenetic (and at times surrealistic) Something Wild in 1986.

In terms of commercial success, The Silence of the Lambs five years later quickly assumed pole position in Demme’s career, and established him as a master of the thriller form; but it was a field he quickly abandoned for the popular but meretricious (and lugubrious) AIDS drama Philadelphia in 1993 and the similarly worthy (and notably inert) Beloved in 1998, based on Toni Morrison’s novel. Since the mid-1980s Demme has been a prolific documentarian, from concert films (such as Stop Making Sense [1984]) to political portraits (Jimmy Carter: Man from Plains [2007]), and it is arguably the case that these are now more representative of his body of work than the larger budget studio pictures he still occasionally helms. His return to the thriller with a remake of John Frankenheimer’s classic The Manchurian Candidate (in 2004) was coolly received, and almost universally found to be wanting when compared to the matchless original, but there has been something of a revisionist upgrading of its reputation of late.

Like many an auteur (from Hitchcock to Bergman), Demme clearly feels comfortable surrounding himself with creative personnel that he has worked with repeatedly: cinematographer Tak Fujimoto, the composer Howard Shore, the sound mixer Chris Newman, the character actor Charles Napier, and others. But such is the panoply of subjects that he has tackled, even this familiar crew do not confer an air of uniformity on his films.

The opening sequence of The Silence of the Lambs, in which we see Clarice Starling running in a sweat suit through a sylvan forest, establishes in economical fashion several things about the character. First of all, of course, there is a certain level of physical fitness – she is able to deal with the variety of obstacles she encounters (including a rope climbing frame), although clearly does not find the activity quite as straightforward as an athlete would; some strain is evident. We also learn (as the sequence progresses) that Clarice is training on an FBI course, and is, in fact, a cadet in the Bureau, held in some esteem (despite her inexperience) by her quietly-spoken boss, Jack Crawford. We see her greet a fellow female colleague, a young black woman, Ardelia – the only friend on her own level we see her interact with during the course of the film. Summoned from the obstacle course even before she has time to shower (and is therefore at a disadvantage, bathed in sweat and hardly looking her best), Clarice is called to the office of her boss, a man we sense she respects and is (simultaneously) slightly intimidated by.

Odd one out? Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster) doesn’t just have serial killers to overcome

Demme here includes a significant shot in which Clarice, catching the elevator, is surrounded male colleagues, introducing early on notions of gender and power which are to be examined throughout the film.

Certain elements in the original novel pertaining to the Jack Crawford character are wisely removed in the film adaptation, such as his anguished visits to the bedside of his dying wife. Although in the source material this is an important element, in the context of the filleting that is necessary when creating a screenplay from a novel, such peripheral elements not only become inessential, but their removal can forge a certain opaqueness which is actually helpful to a particular film (as when Clint Eastwood persuaded Sergio Leone to abandon acres of dialogue when the two worked together in Italy on the ‘spaghetti Westerns’). Here, the streamlining obliges us to regard Crawford (to some degree) from the outside – in precisely the way, in fact, that Starling perceives him. We know no more about him than she does, and this mystique makes the character, and his motives regarding Starling, more intriguing.

This strip-mining of detail for cinematic purposes is in fact one of the signal achievements of the screenwriter Ted Tally, and it is an achievement that will be appreciable only by those familiar with the original novel. A comparison here might be drawn with the books (and subsequent films of) the popular thriller writer of an earlier generation, Alistair Maclean. Many of his later books began to read like treatments for the (inevitable) subsequent films, with all the essential elements shoe-horned in to facilitate the requisite number of set pieces.

PSYCH AND CRIMINOLOGY

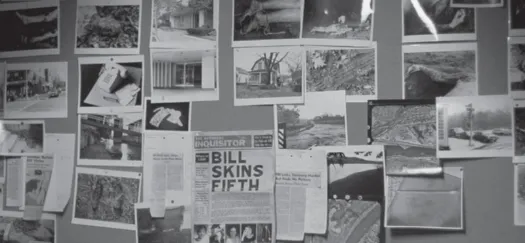

Demme gives us the story of ‘Bill’ and his victims in one shot

On the cork board behind Crawford’s head we see the National Enquirer-style tabloid headline ‘Bill Skins Fifth’, making it quickly apparent to us that a serial killer has become a major priority for the Bureau. Crawford makes it clear that Clarice is to be used in order to obtain information from the incarcerated serial killer Hannibal Lecter to help track down the murderous ‘Buffalo Bill’ – so called because he is removing part of the skin of his victims – before he claims more lives. The FBI is clearly worried about the lack of progress it is making in the case, and similarly, Clarice is conscious about her own personal progress within the Bureau. The opportunity she is offered is, therefore, distinctly advantageous (should it prove successful), for both her and her employers. Clarice has majored in Psych and Criminology at UVA, and has spent time as an intern at a psychiatric clinic, but this assignment is to represent her first engagement with serial killers.

We next see her, now a smartly dressed and capable looking individual, dealing with the unpleasant Dr Chilton, in charge of the Baltimore psychiatric prison in which Lecter is imprisoned. Chilton, who makes inappropriate advances to Clarice (which she politely but firmly sidesteps) gives his own assessment of why Crawford has chosen her for the assignment suggesting that her prettiness is to be used as a tool to ‘turn on’ Lecter (who, we are told, has not even seen a woman in eight years); Chilton remarks that Clarice will be very much to Lecter’s murderous taste (just as she clearly is to the oleaginous Dr Chilton).

Of course, unpleasant though Chilton is, he can hardly match his appalling charge, who has eviscerated nine people and eaten the tongue of a prison nurse. Chilton boasts that Lecter regards him as his nemesis, and points out just how much hatred there is between the two men. This spleen will come to bear an ironic and gruesome fruit later in the film.

FINESSING THE AUDIENCE

The first appearance of Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs is prepared for by Demme and his team as assiduously as any of Shakespeare’s great character entrances (and the psychiatrist shares certain characteristics with his famous forbears, such as a striking charisma – and an overweening self-regard). We have been introduced to the self-regarding, pompous Chilton, and it is here that the work of Demme’s casting director Howard Feuer continues to show impeccable results. Anthony Heald, in the role, is supremely unpleasant. It might be argued that Demme and Feuer are colluding in Harris’s finessing of sure-fire Pavlovian responses in his audience – in other words, the casting strategy shows that they are doing the best possible justice to the tactics utilised by Harris in the original novel. The very capable Heald has clearly been encouraged to be as unattractively oleaginous as possible, with gelled long hair that (in film shorthand) suggests untrustworthiness. By this point, we are already, of course, firmly locked in the consciousness of Clarice, so the doctor’s supercilious manner and apparent contempt for his patients have already rendered him unsympathetic even before his crass attempts at asking Clarice out for a date are rebuffed – an early demonstration of the politeness that is to win Clarice some kudos with Hannibal Lecter (for whom courtesy is a cardinal virtue).

Few works of popular genre cinema have the time (or the interest) to explore the nuances of human behaviour and prefer to delineate such things in bright poster colours (film-makers generally subscribe to HL Mencken’s dictum that nobody ever went broke underestimating the taste – or intelligence – of the public). But this is most certainly not the case with Jonathan Demme and Ted Tally, as evinced by their treatment of the unpleasant attempts at seduction of Clarice by Dr Chilton. Without ever over-stressing the change of attitude in the character when he realises that he will not get very far with his attractive visitor, we witness a sudden froideur in his dealings with her, and his true feelings (which are, it is suggested, of a misogynistic nature) become more apparent. This ties in with the perception of the film as having a progressive feminist agenda (which links it thematically with Demme’s oeuvre), i.e. the suggestion that Starling’s only interest for Chilton is in a libidinous sense; his apparent acknowledgement of her gifts is purely cosmetic – a means to a sexually self-interested end.

THE DEVIL IS IN THE DETAIL

The fact that The Silence of the Lambs is such an exemplary artefact of the screenwriter’s craft may be underlined by the fact that there are actually few non-essential elements in the novel lending themselves to easy removal. The immense amount of novelistic detail in Harris’s original is never there simply to provide texture (as per the facile instructions in a creative writing course) – such detail is always absolutely at the service of finessing elements of character and narrative development; the removal of such material, while de rigueur for the exigencies of fashioning a screenplay is no easy task, though Tally accomplishes it with understated skill. As mentioned earlier, in the universe of the film, we are no longer (as viewers) party to the consciousness of Jack Crawford, or (for that matter) the mindset and psyches of the two killers, Hannibal Lecter and Jame Gumb – or even, it might be argued, directly linked to the thought processes of Clarice Starling. But without the utilisation of a voiceover (a device that simply would not have worked in the game plan established here by the director, removing the shadings which the audience are allowed to fill in for themselves), what we are shown regarding the mental processes of the heroine by the nuances of Foster’s performance and the subtle use of mise en scène to flesh out her character bring an almost novelistic richness to the character, and the removal of certain narrative components is always justified. What is always apparent is the determination of this young woman to make a mark in a man’s world. And here, again, any feminist agenda is never bluntly formulated verbally – one of the many examples of an assumption of intelligence on the part of the viewer. It might be argued that Starling’s need for the blandishments of a masculine authority figure (and the film contains two such, one positive and paternal, the other negative and almost vampiric) ensures that any doctrinaire feminist reading of the film is difficult to sustain. The complexity of Starling’s response to Crawford is somewhat different in the film to that in the novel – in the latter, unaware of the conflict and worry in the FBI chief’s character caused by his wife’s illness, she interprets his unsettling changes of mood as a wavering response to her gender in terms of her suitability for the job. Once again, the streamlining of this element of the book is entirely to the film’s advantage.

After Clarice is instructed by Chilton in the rigorous procedures necessary for any encounter with Lecter (further instilling apprehension in the audience), we are presented with the same antiseptic white walls for Lecter’s place of incarceration that we had seen in Manhunter; but the effect here is not so theatrical (colour is used more naturalistically), and the institution accordingly has a touch more veracity. However, Clarice’s tense walk along the dark corridor to Lecter’s cell is more unsettling than that in the early film, with each cell containing a disturbed (and disturbing-looking) individual, the most unpleasant of whom is unquestionably the gibbering ‘Multiple’ Miggs, who approaches Clarice hoarsely whispering ‘I can smell your cunt!’ And while this obscenity tells the audience all we need to know about this murderous individual, Miggs’ behaviour has a surprising corollary when it is later discussed by Clarice with Lecter. In terms of production design, the contrast of the ‘house of horrors’ corridor with the antiseptic cell at its end is vaguely surrealistic (and even expressionistic). The setting coveys both a possible (if unlikely) option for imprisoning extremely dangerous psychopaths, and is also – at least in Lecter’s case – a visual representation of the killer’s mind, with its Stygian horror film aspect: the dungeon-like corridors with sinister prisoners through which Clarice is obliged to pass (as if on a journey to an anteroom of hell) contrasted with its modern high-tech accoutrements when we finally reach the cell containing Lecter. It boasts a variety of technological devices which allow the psychiatrist a certain degree of diversion while severely restricting his freedom (for the purposes of protecting those who come into contact with this most dangerous of men).

There is perhaps an echo in this sequence of an earlier arcane mix of Gothic horror and modernistic settings: the bizarre art nouveau house of the Boris Karloff character in Edgar Ulmer’s cult film The Black Cat (1934; interestingly, also a film which features the skinning of human bodies, handled with a degree of restraint equal to that employed by Demme). But whereas the futuristic setting of the Ulmer film (from his own sketches) is impossible to ignore, an audience might not notice the intriguing mix of styles in Demme’s prison complex.

The synthesis of elements that create the look and identity of a film come from a variety of talents: from the director’s original conception, to the cinematographer’s realisation of the same; to the production designer. In the case of The Silence of the Lambs, these three elements are in perfect harmony, producing a visual signature for the film which is highly distinctive and very specific to Demme’s vision (different directors have not attempted to replicate the visual style of Demme and co. for later Hannibal Lecter outings). Such elements as the released moths that are given free rein in Jame Gumb’s/Buffalo Bill’s squalid kitchen suggest an environment in which something is subtly wrong. Kristi Zea, the highly accomplished production designer, creates a contrast between very disparate settings: Lecter’s cell, the training ground at the FBI, the oak-panelled courtroom in which Lecter is temporarily incarcerated and the final menace-laden lair of the film’s on-the-loose killer Gumb. And while all these settings are brimming with carefully observed detail (not to mention the sharply observed small-town America with its blue-collar industrial environments) the real achievement of Zea is perhaps one that is not immediately apparent on the first (or even subsequent) viewings of the film – that is to say, creating a cohesive universe against which Thomas Harris’s characters can act out their disturbing scenarios without ever suggesting a lurch from one level of reality to the next. Even Gumb’s house – the nearest the film comes to Daniel Haller’s gothic production design for Roger Corman’s Edgar Allan Poe adaptations – though somewhat over the top (notably with its sunken pit in which the luckless, filthy victims are imprisoned), remains basically grounded in a kind of reality (note the grease-encrusted stove on which Gumb prepares his meals – and possibly uses for more sinister processing purposes).

THE FIRST MEETING

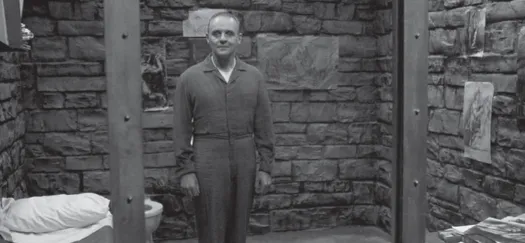

Lecter 2.0: our first sight of Anthony Hopkins

The initial meeting between Clarice Starling and the murderous psychiatrist Hannibal Lecter is one of the great set pieces of modern cinema, justly celebrated, frequently imitated and parodied. While clearly adhering to the imperatives of poplar cinema, the sequence is shot and acted with a rigour worthy of the ‘chamber cinema’ of the Swedish master Ingmar Bergman in his late 1960s films such as Persona (1966) – and this is not the only occasion in which the more rarefied agendas of art cinema are evoked by Demme and his collaborators. As Clarice has made her way past the sinister cellmates who inhabit the same block as Lecter, first time audiences were disarmed by their first sight of a monster for who they might have thought they had been well prepared. They may have been expecting an overtly sinister figure, or perhaps a crabbed, sepulchral one, bound to be physically repulsive in the extreme. The first sight of the actor Anthony Hopkins standing upright and alert in a boiler suit with a fixed smile on his handsome face, short hair neatly slicked back, is the absolute opposite of what audiences have been led to expect given the variety of warnings impressed upon Clarice and the viciousness of Lecter’s crimes. Surely, we think, this not unattractive (if unsettling) figure cannot be the monster we have heard about? The initial response of audiences in 1991 to Hopkins’ first appearance was sometimes a gasp or a snort of laughter – not of derision, but a wry realisation of our own readiness to be led up the garden path and be presented with the last thing we expected – the sight of a charismatic actor. Inevitably, of course, comparisons must be made with the first appearance of Brian Cox in Manhunter, and for all the considerable virtues of the earlier actor’s incarnation of the role, there is an added element here, a dramaturgical consolidation of Hopkins’ performance which Michael Mann did not accord Cox.

Very quickly, Jonathan Demme and his cinematographer Tak Fujimoto establish an almost musical counterpoint in the juxtaposition of close shots of his two actors, and it is this piece of subtly utilised technique which (as much as anything else) renders the scene so effective. Firstly, of course, there is the writing, with Ted Tally’s screenplay utilising many of the perfectly judged lines from the Harris ...