![]()

Part I

BACKSTORIES

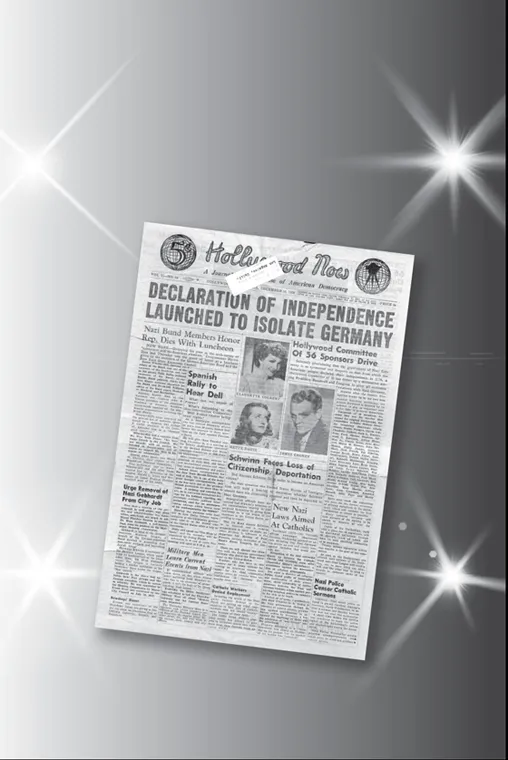

The front page of Hollywood Now, the journal of the Hollywood Anti-Nazi League for the Defense of American Democracy and a forum to celebrate the Popular Front activism of above-the-line talent in the motion picture industry, December 16, 1938. The subscriber is journalist Ella Winter, wife of the league’s co-founder, screenwriter Donald Ogden Stewart. (Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University)

![]()

Chapter 1

HOW THE POPULAR FRONT BECAME UNPOPULAR

Given the climate of the times—the shadow of the Great Depression, the backfire from World War II, and the atmospherics of the emergent Cold War—the face-off between Washington and Hollywood staged in October 1947 seems preordained, a perfect storm converging with the predictability of an end-reel clinch—or, to borrow another dialectic, clashing with the kind of “historical inevitability” that the unfriendly witnesses were so fond of. A major confrontation had been brewing for at least a decade and, after the hiatus born of mutual advantage during the late war, an ugly showdown arrived right on schedule.

The immediate pressure system was the Cold War, the long twilight struggle declared with the slamming down, not the raising of, a curtain. On March 5, 1946, at Westminster College, in Fulton, MO, former British prime minister Winston Churchill conjured the image that crystallized American fears of Soviet expansionism and shaped the geopolitics of the postwar world. “From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the Continent,” intoned the oracle with a proven track record. Reprinted, rebroadcast, and replayed in the newsreels (Churchill’s left hand sweeps down for emphasis when he utters the magic words), the mental picture so vividly evoked the iron fist of tyranny and the final curtain of death, that the phrase quickly entered the vocabulary. Soon enough, it would also serve as the high-concept title for a Hollywood thriller.

Yet no less than the recently declared Cold War, the movie-minded hearings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities grew out of the tensions and traumas of the Great Depression and World War II. Whether on the dais or at the witness table, the contestants shared the felt experience of economic chaos and mortal danger—a deep-in-the-bones dread that catastrophe was lurking just around the corner. To the Depression-born, war-tempered generations, the world was always just a turn away from spinning off its axis. Early warning signs had to be heeded and alarms sounded.

A lot of the history—both backdrop and ongoing—was bound up with the great art-business-technology that had come to vital maturity by the mid-twentieth century. The long purgatory of the Great Depression and the horrors of World War II were boom times for the motion picture industry. Even as first hardship and then war convulsed the nation, Hollywood ripened into a sinuous, streamlined oligopoly commanding center stage in American culture—and acquiring enormous power to mold opinion, embed values, and transform thinking.

Philip Dunne: “They liked Roosevelt and they hated Hitler.”

Hiding its transformative impact behind a soothing cover story, prewar Hollywood posed as a factory town cranking out frothy diversions to a careworn public. In 1941, in a statement prepared for the U.S. Senate, Will H. Hays, president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA), declared that motion pictures belonged to the realm of fine art, as distinct from the art of persuasion. Hollywood’s sole purpose in American life was to entertain and give pleasure.1 It was not entangled by political alliances; it was beyond them, above the fray.

Off screen, however, the salaried employees were undercutting Hollywood’s official stance as a neutral port. In 1932, for the first time, a cast of A-list motion picture artists sailed into the tempest of election year politics—most rallying around Franklin Delano Roosevelt, a few siding with the Republican alternative. Over the course of four election cycles, Hollywood would remain a safe precinct for FDR, but the ferment of the Great Depression was not to be calmed by a single outlet for activism. Thousands of workers in the motion picture industry, both big-name stars and toilers in the trenches, aligned themselves with a more radical and emotionally satisfying movement for political and cultural reform, the Popular Front.

Neither a letterhead organization nor a doctrinaire belief system, the Popular Front was the open-ended rubric for a loose confederation of progressive peoples of all stripes: mainstream FDR Democrats, liberals, socialists, and Communists, all united in a shared commitment to civil rights and economic justice at home and the defeat of Fascism—Spanish, Italian, and especially German—abroad. For the disparate factions in the ranks, the ties that bound—a fidelity to the principles of the New Deal and an antipathy to the rising tide of Fascism in Europe—were stronger than the internecine conflicts. Screenwriter Philip Dunne, a member in good standing, summed up the sentiments: “They liked Roosevelt and they hated Hitler.”2

Of all the Popular Fronters, the cadre with the deepest commitment and most tireless work ethic were the Communists. Lit with a religious devotion to the Marxist-Leninist gospel, brooking no deviance from the official doctrine—“the party line”—of the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA), the Communists served as the shock troops of the movement, logging the longest hours on picket lines and doing the grunt work of on-the-shop-floor organizing. They wrote pamphlets, pinned up broadsheets, handed out leaflets, fired off letters to newspaper editors, hand-cranked mimeograph machines, and took on every mundane, thankless task essential to the efficient operation of a political action group. The Communists may have liked FDR and the New Deal, but they loved Joseph Stalin and the people’s paradise aborning in the USSR.

Communism had never had much purchase in America—a nation too individualistic, too religious, and too prosperous for a communal, atheistic, and class-based ideology to take root. Even in the nadir of the Great Depression, when conditions seemed ripe for a revolutionary groundswell, the CPUSA attracted fewer dues-paying members (peak membership in 1939 never surpassed one hundred thousand) than did conservative Irish-Catholic societies in New York City alone.3

Nonetheless, while the broad spectrum of Americans remained deaf to the siren call of dialectical materialism, intellectuals and artists harkened to the sound with alacrity. The Leninist notion of a vanguard elite—of a self-selected band of creators and thinkers leading the benighted masses out of their false consciousness into the revolutionary dawn—proved irresistible to a class of workers who were more likely to be punch lines than heroes in their native land. The Communists put artists and intellectuals front and center in the battle for a new American Revolution.

A momentous shift in CPUSA orthodoxy facilitated the flow of Communism into the main currents of American cultural life. In 1935, the Comintern, the Moscow-based command center for international revolution, sent out a directive to Communists worldwide to forge alliances with heretofore counterrevolutionary pariahs—socialists, liberals, and New Deal Democrats. With Fascism ascendant in Italy and Germany, the ultimate defeat of capitalism would have to be postponed to drive off the wolves at the door. Making the best of the marriage of convenience, American Communists cloaked Soviet policy in native garb. “Communism,” proclaimed Earl Browder, general secretary of the CPUSA, was but “twentieth century Americanism.”4

In Hollywood, as elsewhere, the Communists got with the program. In foreign policy, the prime objective was to end American neutrality and intervene on the side of the Soviet-backed Republicans in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), the fraternal bloodbath seen as the preliminary bout in a future conflagration. In domestic policy, the Popular Front showed an unstinting support for civil rights, especially for African Americans, and the cause of labor over management.

That last cause—broader rights and rewards for the ranks of American labor—had immediate application on the soundstages and backlots of Hollywood.

Willie Bioff: “You got to be tough in this den of hyenas.”

The history of labor relations in Hollywood is as tangled as the wiring on a studio soundstage, a story of broken circuits, crossed currents, and major blowouts. Greed and altruism, gangsters and idealists, pedantic argument and explosive violence—the off-screen action by the workers who built the scaffolding and the writers who sketched the blueprints generated enough pulse-pounding action and backbiting melodrama to fill out a season’s worth of programming produced at the site of the job actions.

Like any industrial machine shop, the dream factory demanded highly organized and compartmentalized teams of skilled workers; it was a shop floor where any malfunctioning cog could cause the whole operation to grind to a halt. The transition to sound technology launched with The Jazz Singer (1927) exponentially increased the need for precision teamwork and expert wranglers.5 For every gauzy close-up on screen, dozens of grimy hands toiled outside the frame to get the shot.

Chicago-bred mobster Willie Bioff, head of the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees, leaves federal court in New York after pleading not guilty to charges of violating federal anti-racketeering law, June 12, 1941.

Of course, in a city obsessed with billing, all Hollywood workers were not equal. The major status division was between the “above the line” royalty and the “below the line” vassals, a boundary that separated the high-priced creative talent (directors, screenwriters, and actors) from the working stiffs whose names were not in the credits much less up in lights. Reflecting a hierarchy of prestige and salary, the artists at the top of the ladder formed guilds not unions, with higher standards for admission as befit the fatter paychecks, while the blue-collar workers who set up the lights, the cameras, and the rest of the action gravitated into craft unions dedicated to their unique skill sets.

In 1925, after nearly a decade of failed attempts, the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees and Moving Picture Machine Operators of the United States and Canada (IATSE) managed to organize the independent craft unions (working on shop floors that were not yet called soundstages) into a united front. Born as a theatrical union in the mid-nineteenth century, IATSE looked upon the motion picture business as a logical extension of its backstage hammerlock on the theater. It became—and has remained ever since—the preeminent omnibus union in the American motion picture industry. In 1926, it used its clout to negotiate the first union agreement in Hollywood history, the Studio Basic Agreement, a simple two-page document that served as the cornerstone for labor-management relations throughout the classical studio era.6

In March 1933, FDR’s New Deal and the labor-friendly outlook of the National Industrial Recovery Act, and, in 1935, the creation of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) under the Wagner Act, encouraged workers throughout American industry to lock arms. Unionization was now a federally guaranteed right—if not a studio-sanctioned activity. Accustomed to ruling their domains with the iron fist of the Asian overlords they were named for, the moguls fought tooth and nail to undermine worker solidarity, whether on the soundstage or at the typewriter.

Under the Roosevelt administration, however, not even the moguls could halt the forward momentum of organized labor. In 1935, pursuant to the Wagner Act, the studios negotiated a closed shop with IATSE, ceding hiring power to the union. Other major trade unions such as the American Federation of Musicians, the International Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners, the Transportation Drivers, and the International Brotherhood of Electric Workers cut similar deals. Henceforth, whether on the soundstage or on location, to work in the motion picture industry required a union card—a golden ticket granting admission to a secure berth.

IATSE emerged from the negotiations with serious clout: it basically controlled the levers to the industrial infrastructure of motion picture production and exhibition.7 In any dispute with the studios, IATSE held an unbeatable trump card—control over the exhibition end of the business. The leadership could order every projectionist in the union to walk out of every projection boo...