![]()

1

INTRODUCTION

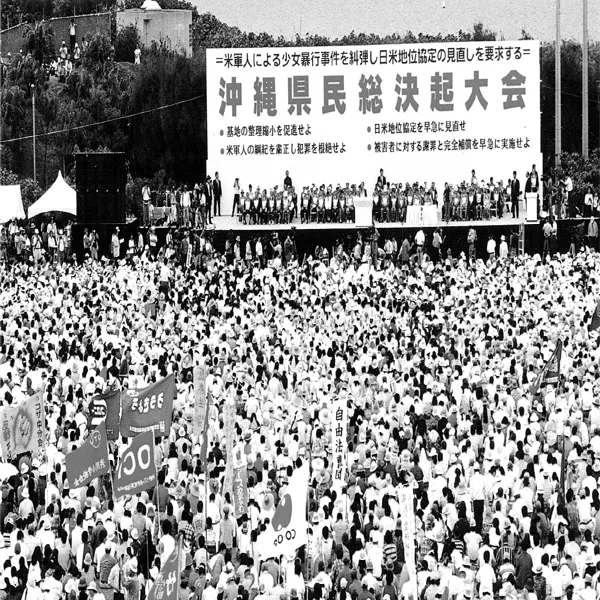

In the autumn of 1995, a twelve-year-old Okinawan schoolgirl was abducted and raped by three U.S. servicemen. The incident immediately set off a chain of protest activities by women’s groups, teachers’ associations, labor unions, reformist political parties, and various grass-roots organizations across Okinawa prefecture. Shortly after, these activities culminated in an all-Okinawa protest rally attended by some 85,000 people from all walks of life, including business leaders and conservative politicians in Okinawa who had seldom raised their voices against the U.S. military presence. On stage, Governor Ota Masahide as much summarized as orchestrated Okinawa’s exasperation by stating, “As the person granted responsibility for administering Okinawa, I would like to apologize from the bottom of my heart that I could not protect the dignity of a child, which I must protect above all else” (Ryukyu Shinpo, October 22, 1995). Although certain sectors of Okinawan society—such as the Military Land-lord Association, whose members had benefited economically from the presence of the U.S. military—remained silent about the matter, the rape incident exposed what the U.S. and Japanese governments long wanted to hide—that Okinawa’s prolonged sufferings derived from, among other things, the disproportionate concentration of the U.S. military facilities there. In fact, in its role as a strategic outpost for “stability and prosperity in the Asia-Pacific region” (U.S.-Japan Security Consultative Committee [1996] 1997: 26), this “remote,”1 semi-tropical island prefecture (population 1.3 million), which makes up only 0.6 percent of Japan’s total landmass, had been burdened with 75 percent of the U.S. military facilities and 65 percent (approximately 29,0002) of the 45,000 American troops in Japan.

FIGURE 1.1 85,000 Okinawans participated in a protest rally against the rape of an Okinawan schoolgirl by U.S. servicemen. Reprint from Okinawa Prefectural Government 1997: 9.

Okinawa’s collective will for the reorganization and reduction—if not the outright removal—of the U.S. bases took definite shape specifically when Governor Ota gave Tokyo a refusal to renew the lease of Okinawa’s land for the use of the U.S. military. In doing so, Ota, as it were, attempted to redeem not only the dignity of the raped girl but also the pride of Okinawans that had long been infringed upon.

Okinawa, once known as the Ryukyu Kingdom, had flourished from the fourteenth through the sixteenth centuries by participating in China’s trans-Asian trade network. In 1609, however, Satsuma, the southernmost feudal clan of the Tokugawa regime in mainland Japan, invaded the Kingdom in order to gain control of the profits made from that trade. For 270 years following this invasion, the Kingdom, while keeping up its appearances as an independent state whose status was formally sanctioned by Ming and Qing China, was in actuality politically and economically subordinated to Satsuma, and by implication, Tokugawa Japan (Kerr 1958, Takara K. 1993, Arashiro 1994). In the late nineteenth century, the newly instituted Meiji government disposed of the Ryukyu Kingdom by way of the “Ryukyu Measures” in order to turn it into a prefecture of Japan. From that moment on, Okinawan customs and manners became, in the eyes of Meiji government officials, the general public in Japan, and in some instances, Okinawan leaders themselves, a symbol of “backwardness” and an obstacle to making Okinawans genuine subjects of Imperial Japan. This view warranted the Meiji government’s implementation of assimilation/Japanization programs for helping, or really making, Okinawans acquire “standard” Japanese, register with the conscription system, and show their allegiance to the emperor.

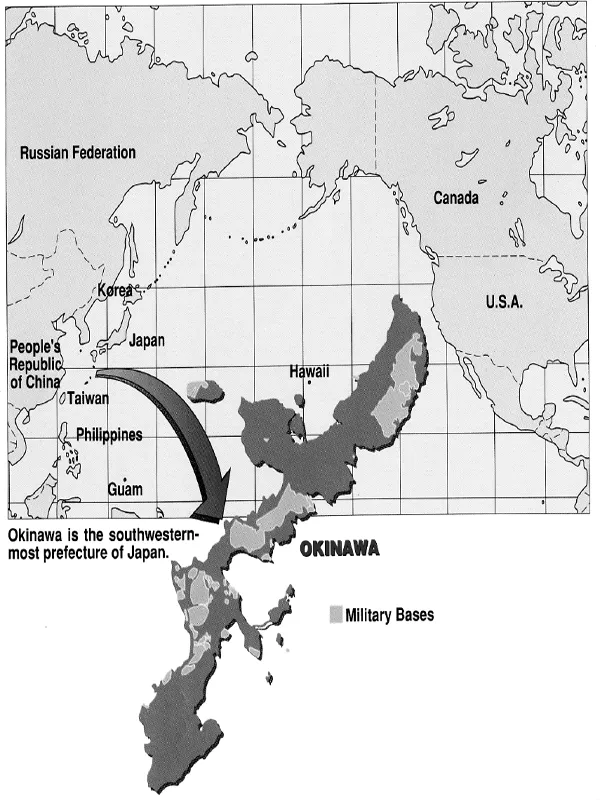

FIGURE 1.2 Map of Okinawa. Reprint from Okinawa Prefectural Government 1997: 2.

The image attached to Okinawans as the second-rate nationals eventually led Imperial Japan to use Okinawa as a strategic sacrifice to protect its mainland from U.S. military attack. In 1945 Okinawa became the site of the fierce ground battle known as the “typhoon of steel,” in which approximately 150,000 lives—about a quarter of the prefectural population—were lost. The hardships of Okinawa did not cease with the war, however. In spite of the pretensions (or efforts, depending on the perspective) of the U.S. military government—named the United States Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands (USCAR)—to make Okinawa a showcase of democracy, violations of human rights were incessant during its period of control (1945–72). The requisition of Okinawa’s land to construct military bases, the acquittal of U.S. servicemen who raped and/or murdered Okinawans, and the purge of the publicly elected mayor of Naha, Okinawa’s capital city, who was critical of USCAR, are just a few examples of the inhumanity Okinawa experienced under USCAR’s rule.

In response, in the 1960s, intense, island-wide reversion movements emerged, wherein the motherland, Japan, was imagined as the guardian of democracy and peace. Thus, Okinawa ironically submitted itself to an exploitative relationship even after the administration of Okinawa was transferred from the United States to Japan in 1972, because, by taking advantage of Okinawa’s desire to escape alien rule, the “guardian,” the Japanese government, agreed with Washington on the continued stationing of the U.S. military in Okinawa in order to counter the “communist threat” in the Far East and beyond. The end of the cold war did not stop the U.S.-Japan alliance from using Okinawa for the purpose of security. In 1995, the Pentagon declared—and Tokyo acknowledged—that “Asia remains an area of uncertainty, tension, and immense concentrations of military power” (Department of Defense 1995: 2), and reaffirmed its commitment to maintain a stable forward presence in the region (approximately 100,000 troops) into the foreseeable future.

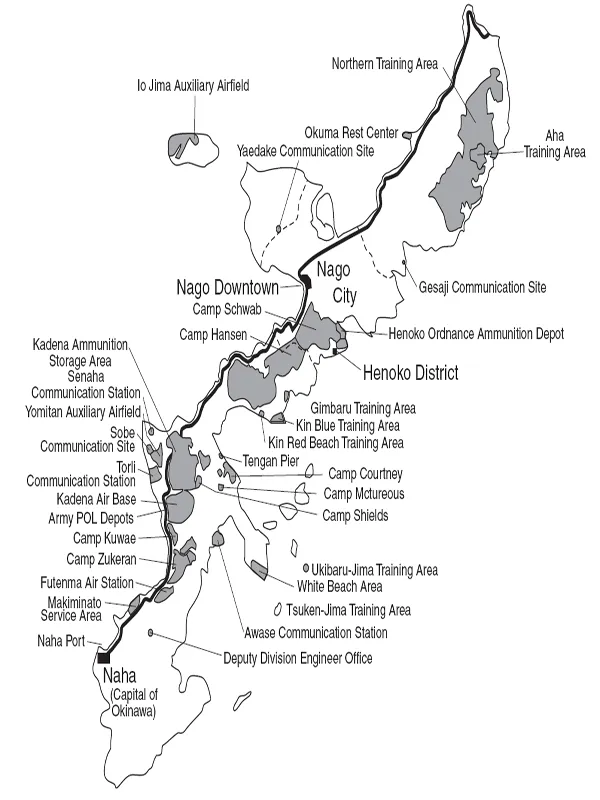

The 1995 rape incident took place in the midst of this politico-military reaffirmation. In a way that undermined the security planning of Washington and Tokyo, the incident rekindled Okinawa’s sedimented, smoldering sense of injustice, for which the apologies of President Bill Clinton, Ambassador to Japan Walter Mondale, Secretary of State Warren Christopher, and Secretary of Defense William Perry, and the promises of the Japanese government to reduce the burden on Okinawa, were like sprinkling water on parched soil. In November 1995 the U.S. and Japanese governments established the Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) to deal with Okinawa’s anger. In December 1996 SACO proposed that some of the major U.S. military facilities be returned to Okinawa by 2003 (Special Action Committee on Okinawa [1996] 1997). Among these was the 500-hectare (1,235-acre) Futenma Marine Corps Air Station,3 which was one of the largest U.S. military bases in the Far East and was located in the congested residential area of central Okinawa.

It should be noted, however, that this proposal was only a part of an overall package that was designed more for the security goals of Washington and Tokyo than for the welfare of Okinawans. The main feature of the proposal was to establish and maintain a stable military presence in the region. Indeed, together with the return of Futenma, SACO also proposed the construction of a sea-based military base as its replacement facility off the waters of Camp Schwab in Henoko District (population: 1,400), a sparsely populated eastern coastal district of Nago City (population: 55,000). The Okinawans, however, viewed the idea of building a new base as an excuse to create a permanent U.S. military settlement and to strengthen its base functions. As a result, there was intense opposition from not only local residents but also from Okinawans everywhere. In 1998 Governor Ota declared that Okinawa was rejecting the proposal to construct the offshore base and, together with Okinawan citizens opposed to the base, demanded the unconditional return of Futenma. With this rejection, steps were to be steadfastly taken to reorganize and reduce the U.S. bases in Okinawa—or, so it appeared.

FIGURE 1.3 Futenma Air Station. Reprint from Okinawaken Sōmubu Chiji Kōshitsu Kichi Taisakushitsu 1998a: 19

FIGURE 1.4 Camp Schwab. Reprint from Okinawaken Sōmubu Chiji Kōshitsu Kichi Taisakushitsu 1998a: 6

FIGURE 1.5 Map of Military Bases in Okinawa. Reprint from Okinawa Prefectural Government 1997: 4.

However, today, with the promised year of 2003 behind us, one finds that little change has come to Okinawa. Late in 1998, Governor Ota, the emblem of Okinawa’s protest against the 1995 rape, was defeated in his bid for reelection. Originally, SACO had promised to return eleven military facilities to Okinawa, but only two have been restored thus far. The operations of Futenma Air Station have remained intact. In the community of Henoko in Nago City, preparations for the construction of the replacement facility of Futenma have been under way. U.S. servicemen raped Okinawan women even after the 1995 incident; the number of crimes committed by U.S. military personnel in Okinawa has tended to increase since 1997 (Okinawa Taimusu, June 3, 2004; Okinawaken Sōmubu Chiji Kōshitsu Kichi Taisakushitsu 2003).4 Earsplitting daily jet noise and land pollution have also continued. Military accidents, too, continue to occur; in August 2004, for example, a U.S. Marine helicopter crashed into a university campus in central Okinawa.

Meanwhile, the functions of U.S. bases in Okinawa have been redefined as a forward presence to fight, no longer against “communist threats,” but now, in the context of the post–cold war security environment, against “the unknown, the uncertain, the unseen, and the unexpected,” to transplant the words of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (2002: 23) from his discussion about “Transforming the Military.” In alignment with this new strategic goal, Washington dispatched more than three thousand marines from Okinawa to the 2003 Iraq War, and now proposes to use not only Okinawa but Japan as a whole as a strategic foothold called “Power Projection Hub” (Korea Times, May 19, 2004; Asahi.com, September 22, 2004). In short, the sober reality is that Okinawa’s protests in and since the late 1990s have not helped restrain, let alone overthrow, the power of the U.S. and Japanese governments. Rather, power has paradoxically kept self-valorizing in spite of, and in the midst of, Okinawa’s resistance.

Harvard sociologist Ezra Vogel (1999:11) approached this paradox by posing the question of why “Okinawans voted against Governor Ota and in favor of a man more willing to accept Tokyo’s largesse and to keep a substantial U.S. military presence in Okinawa [?]” His conclusion: “In short, Okinawans were willing to provide facilities to U.S. troops to get economic aid from Tokyo.” Challenging and complicating a reductionist economic view of this kind, my study, for its part, aims to give this paradox an anthropological—that is, ethnographic, historical, and theoretical—explanation by exploring the intricacies of Okinawan identity in the context of the nation-state and the larger processes of global history. Specifically, I conceptualize old cultural sensibilities of a uniformly poor and homogeneously oppressed Okinawan “people” in terms of a notion of totality, “we are Okinawans,” and underscore how this totality—which had been shaped and reshaped by Okinawa’s collective experiences of Japanese colonialism, the war, and U.S. military control—were, by the 1990s, increasingly rearticulated and sometimes disrupted by emerging internal differences. My intuition is that these internal differences that have both renewed and dislodged Okinawa’s unified front against the U.S.–Japan alliance, thereby helping us explain the puzzle of how and why power has multiplied in the midst of resistance. I will substantiate this intuition in three steps.

First, I introduce the general problematic of Okinawan modernity that has defined basic parameters of local identity (chapters 2 and 3). In chapter 2, the historical origin of Okinawa’s oppositional sentiment will be discussed, together with how the affluence of contemporary Okinawan society—made possible by massive economic aid from Tokyo since the reversion of Okinawa in 1972—has acted as a background and vehicle of the unsettling transformation of this oppositional sentiment. The analysis of the unified protest against the 1995 rape specifically allows us to catch a glimpse of the larger historical process whereby the pan-Okinawan social consciousness of “we are Okinawans” has been articulated no longer in the sentiment as a poor, oppressed “people” but increasingly in the perspective of affluent “citizens” of diverse backgrounds awakened to globally disseminated ideas about ecology, women’s equality, and peace.

Chapter 3 examines the same problematic of Okinawan modernity—Japanese domination, the war, U.S. rule, and the postreversion affluence—from the standpoint of the production of knowledge. Situating knowledge on Okinawa at a crossroads of local, national, and transnational circuits of intellectual discourse, this chapter specifically presents a critique of the body of “modern” Okinawan studies—three distinct but interrelated intellectual traditions concerning Okinawa that were developed between the 1920s and the 1980s in Japan, the U.S., and Okinawa, respectively.

My critique centers on their tendency to appeal to pure or original Okinawan-ness outside power and history by excluding the U.S. military and related social problems from their analyses. By delineating the contour of “modern” Okinawan studies, this chapter also wants to register and highlight the thrusts of new, critical, “postmodern” studies of Okinawa, within and against which this study is situated.

The second cluster of my study (chapters 4 and 5) ethnographically examines, on the basis of the fieldwork I have been doing since the summer of 1997,5 the politics of identity in a specific place in Okinawa—the community of Henoko in Nago City. The readers will recognize that Henoko, as the proposed site for the relocation of Futenma Air Station, was and is the very center of the issue of military bases in Okinawa in spite of its small population and its marginal political status. In reference to the historical arrangement that had made this community in northern Okinawa home to U.S. Marine Corps Camp since 1957, I will highlight Henoko as a developmental twilight zone which, while partially sharing in the affluence of postreversion Okinawa at large, has nonetheless been left behind as compared to more prospering south and central Okinawa. In the process, I will conceptualize the production of a sometimes reluctant and at other times enthusiastic pro-base6 position in Henoko in reference to the idea “we are Okinawans but of a different kind.” This idea specifically led Henoko’s working-class residents to support, often against the grain, the U.S. military presence in exchange for jobs (chapter 4), while at the same time rousing the anti-base sentiment within this community among middle-class residents in reference to the enduring idea of pan-Okinawan unity, “we are Okinawans” (chapter 5).

In chapters 4 and 5 specifically, and in this study generally, the working class, a term that is admittedly somewhat awkward but useful, refers to “the socioeconomic class consisting of people who work for wages, especially low wages, including unskilled and semiskilled laborers and their families” (The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, fourth edition, s.v. “working class”; Cf. Williams 1983: 60–69). In Henoko, and by implication Okinawa at large, they are, for example, construction workers, petty engineers responsible for maintaining equipment, delivery men, taxi drivers, employees in the food service industry, store clerks, and workers in the U.S. bases. The middle class in this study is defined as the socioeconomic class consisting of people who, while working for wages (like all workers), do so in more secure conditions with a greater degree of autonomy and comfort than workers of the working class. Within Henoko, and by implication Okinawa at large, they are, for example, public employees, educators, health-care professionals, journalists, intellectuals, retirees with lifetime pensions,...