![]()

I

Why Invest in Frontier Markets?

![]()

1

Emerging Markets Have Emerged

On September 29, 2009, I wrote an article in the Financial Times announcing that the term “emerging markets” was obsolete. What traditionally distinguished developed from emerging markets, I argued, no longer applied. My assertion was bolstered by the Group of Twenty (G-20) meeting four days earlier in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where the gathered finance ministers and central bank governors officially declared that the G-20 would replace the G-8 as “the premier forum for international economic cooperation” in recognition of the new reality of the global balance of power.1 Of the nineteen countries in the G-20 (the European Union is the twentieth member), eleven are emerging or frontier markets.2

Emerging markets have emerged, and they are bigger and more integrated with the global economy than you might think.

• China now buys more cars than the United States, and in fact requires so many commodities to fuel its growth that in 2007 it bought a 15,000-foot mountain in Peru for the two billion tons of copper inside.

• The first non-American name on Forbes’s 2015 list of the world’s most valuable brands is the Korean company Samsung, beating out Toyota, General Electric, Facebook, and Disney.3

• The countries with the most Facebook users after the United States are India, Brazil, Indonesia, and Mexico—all mainstream emerging markets.4

As emerging markets become more like developed markets, investors have the opportunity to enhance their portfolios by increasing their exposure to emerging markets. But there’s a flip side: The characteristics that once made emerging markets so appealing to the adventurous investor (their potential for much greater growth at a much lower price, for instance) are also beginning to fade. Those investors will want to turn their attention to frontier markets, to which I devote the rest of the book. But I’d like to start with a look at the emergence of emerging markets, which will help put into context both the possibilities and the challenges that frontier markets present.

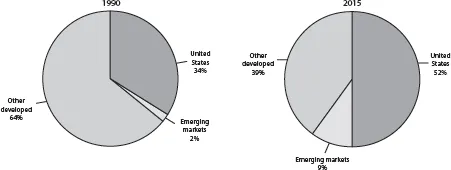

Although emerging markets are growing in importance, they are still underrepresented in existing global benchmarks. Index provider MSCI’s All Country World Index (ACWI), comprising twenty-three developed and twenty-three emerging countries as of this writing, has given increasing weight to emerging markets over the last quarter century. Its weightings, however, would still seem to indicate that emerging markets are not very important—warranting some interest, but considerably less so than developed markets. In fact, nine of the twenty-three countries that MSCI considers emerging are given so little weight in its indices that I categorize them as frontier markets. In 1990, one year after the fall of the Berlin Wall and shortly after Deng Xiaoping liberalized China, emerging markets represented only 2 percent of the MSCI ACWI. Twenty-five years later, the emerging markets weighting in the ACWI had grown to only 9 percent—a grossly insufficient representation of their true importance in the global economy (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

MSCI ACWI weightings, 1990 and 2015.

Source: MSCI.

I have argued for many years that this underrepresentation of emerging markets in global benchmarks is a mistake. Because of this artificial classification—“emerging markets”—these markets are much smaller in investors’ portfolios than their importance and the magnitude of their opportunity warrant, which could lead to the long-term underperformance of these portfolios. Given the lucrative opportunity of these markets, why are they so neglected? The historical arguments against emerging market investments usually fall into four broad categories: the size of their economies, the size and volatility of their markets, their government policies, and their corporate governance. I believe, however, that these differences are in the process of blurring or have disappeared completely.

The Size of Emerging Market Economies

Emerging market economies are no longer the insignificant players in the global economy that they once were. Eighty-seven percent of the world’s population now lives in emerging markets, including over half in the fourteen mainstream emerging markets. And the economies of emerging markets are in aggregate bigger than developed markets. The rapid growth of emerging markets in the past two decades has made any distinction based on size largely obsolete.

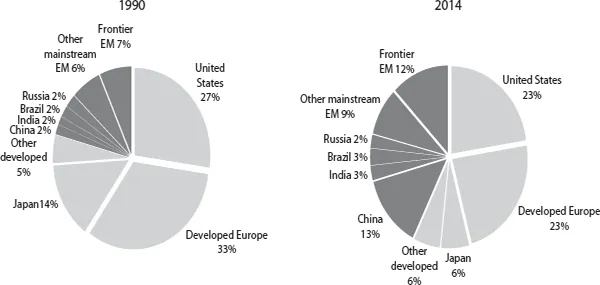

In 1990, when emerging markets were just a sliver of the MSCI ACWI, they represented 21 percent of the world economy (figure 1.2). The four largest emerging market economies—Brazil, Russia, India, and China (the BRICs)—accounted for 8 percent. Although the United States and Europe were the dominant economies back then, and Japan was large as well, emerging markets were already a meaningful portion of the world’s GDP. By 2014, emerging market economies had grown substantially, with almost a third of the world’s GDP (measured in U.S. dollars) generated in the mainstream emerging markets. Taken together, the BRICs accounted for 21 percent, the majority of which was China. But while investor attention has focused on the BRICs, the remaining mainstream emerging and frontier market countries are just as large a share of the global economy. Based on U.S. dollar GDP, non-BRIC emerging market equity investments should nearly match the size of a typical global investor’s investments in the United States.

Figure 1.2

Share of world economy based on US$ GDP, 1990 and 2014.

Source: IMF; World Bank.

The Power of Purchasing Power Parity

Although this measure of global GDP shows the growing importance of emerging markets, it actually still underrepresents these markets because it is calculated using current U.S. dollars. Depending on the local currency, this methodology may overvalue or undervalue a country’s (or an entire region’s) true percentage of world GDP. Those who consider the euro to be overvalued would see that as a reason why developed Europe’s GDP in U.S. dollars is so large. Conversely, many Asian countries keep their currencies undervalued through government interventions, so their GDPs when measured in U.S. dollars understate their true contributions to the global economy.

Rather than using U.S. dollar GDP to measure the size of an economy, I find it more useful to look at economies adjusted for purchasing power parity (PPP), where one “international dollar” purchases the same quantity of goods and services in all countries. This is a more accurate way of looking at the world, because it accommodates not only exchange rate undervaluations and overvaluations, but also the fact that items in an emerging market may sell for a fraction of what they do in a developed market. If income in emerging country E is half the income in developed country D, but the cost of a phone call in E is only one-quarter the cost in D, then phone calls are twice as affordable in E as in D; the growth potential for a phone company in E is therefore much larger than for a phone company in D.

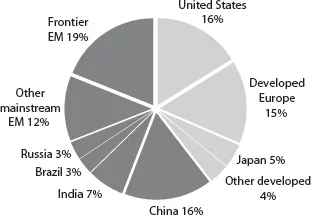

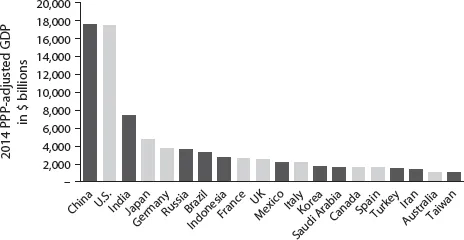

Figure 1.3 illustrates how PPP-adjusted GDP reflects what I consider the true size of emerging markets: Emerging and frontier markets now generate 60 percent of the world’s PPP-adjusted GDP, including 41 percent by the mainstream emerging markets. In fact, the BRICs are together bigger than all the developed markets in the world combined excluding the United States. On a PPP basis, China is now larger than the United States; India is 50 percent larger than Japan; Russia, Brazil, and Indonesia are larger than France or the United Kingdom; and Mexico is larger than Italy (figure 1.4).

At nearly 30 percent of the global economy, the BRICs are obviously important. But what is more interesting to me is that the ten non-BRIC mainstream emerging markets (Mexico, Indonesia, and Korea, for example), while not large individually, are together 12 percent of global GDP. This makes their contribution, collectively, close to one-and-a-half times the combined economies of all the developed markets outside of Europe and the United States (Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Israel, Japan, New Zealand, and Singapore).

Figure 1.3

Emerging markets are now 60 percent of global PPP-adjusted GDP.

Source: IMF; Authors.

Figure 1.4

Emerging/frontier markets are eleven of the top twenty largest economies.

Source: IMF.

Distinguishing developed from emerging markets based on the size of their economies alone no longer makes sense. For investors, this is a very important point to keep in mind.

The Size of Emerging Market Financial Markets

Investors often think of emerging markets as having small, illiquid financial markets. But increasingly, emerging markets are larger and more liquid than many developed markets, with similar volatility.

Market Capitalization and Liquidity

The market capitalization of emerging markets has increased substantially over the last two decades, propelled by much faster economic growth than in developed economies. The listing of many private and government-owned companies during this period has also boosted the overall size of emerging equity markets. As a result, emerging markets are now larger and more liquid than ever before, making it easier for investors to increase their emerging markets exposure.

Mainstream emerging markets, in total, currently represent 22 percent of the world’s equity market capitalization, up from 10 percent a decade ago. Mainstream emerging markets are truly “regular” markets with nearly $16 trillion of investable assets, and an investor can take advantage of this. Some of the larger emerging markets are viable alternatives to better-known developed markets. China’s equity market, for instance, is now larger than Japan’s; Korea and Taiwan, two emerging industrial powerhouses, are together larger than Germany; and Brazil is as large as Spain.

Liquidity in emerging markets has also increased dramatically. In 2014, Chinese markets traded more dollar volume than the NYSE (several times more during the first half of 2015, in fact), and Korea, India, Brazil, and Taiwan each traded more than Switzerland. Liquidity is clearly more than adequate in many of these markets.

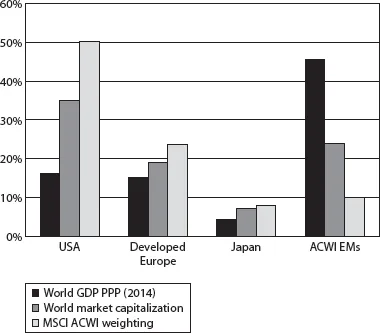

Even for active investors who do not try to passively mimic a benchmark, I believe indices like the MSCI ACWI do influence the way they look at the world. The United States is by far the most overrepresented market, with a much larger weighting in the MSCI ACWI than its share of global market capitalization or GDP would warrant (figure 1.5). Europe and Japan are also overrepresented, but not as egregiously.

Figure 1.5

Benchmarks are not doing you a favor: weightings by GDP, market capitalization, and index.

Source: IMF; World Bank; Bloomberg; MSCI.

Meanwhile, the twenty-three emerging markets in the MSCI ACWI (the fourteen I consider mainstream emerging plus the nine smaller markets I consider frontier), which represent 45 percent of the world’s GDP on a PPP-adjusted basis and 23 percent of world market capitalization, account for just 9 percent of the index. Benchmarks are therefore placing investors at a disadvantage as they underrepresent the current and future impact of emerging markets. Anyone investing based on benchmarks is looking in the rear-view mirror.

Volatility

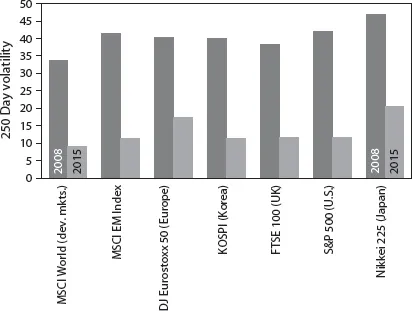

In addition to market capitalization and liquidity, some investors cite volatility as an argument against investing in emerging markets. This common misperception is costing them money. Based on quantitative volatility measures, emerging markets and developed markets look much the same. In 2015, emerging markets as a whole were less volatile than Europe, and volatility in individual markets such as Korea matched the volatility of the United Kingdom and the United States (figure 1.6).

Figure 1.6

Emerging markets’ volatility similar to developed markets during and after crisis.

Source: Bloomberg.

Interestingly, in the extreme market environment of 2008, emerging markets were about as volatile as the S&P 500 and the major European indices, and less volatile than Japan; all of these markets’ volatilities were in the high thirties to mid-forties. Even in the midst of a global financial crisis, emerging markets behaved similarly to developed markets.

Emerging markets are comparable to developed markets in size, liquidity, and volatility, and the prudent investor should not discriminate against them based on these criteria.

Government Policy

A third line of argument against emerging markets is that their economic policies are unpredictable. Many emerging markets in the past intervened to manage their currencies—weakening them to boost exports, for instance—and were criticized for this by the developed markets and the IMF. Similarly, several Asian countries in 1997–1998 suspended short selling and took other measures to support their stock exchanges. When countries in Latin America and Asia implemented such measures, the United States and Europe lectured them on government policy best practices, urging them to let the free market take care of itself.

Ironically, having criticized emerging government interventions in the 1...